4 former executives blamed for Fukushima nuclear disaster and ordered to pay $97 billion to shareholders

July 14, 2022

Four former heads of Japanese utility Tokyo Electric Power Co. have been ordered to pay 13.32 trillion yen ($97 billion) for the damages caused by the Mar. 11, 2011, Fukushima nuclear power plant meltdown, as the country continues to struggle to deal with the aftermath of the disaster.

In the first case to lead to a verdict against TEPCO executives, presiding judge Yoshihide Asakura found that the leaders of the company at the time had failed to properly prepare for a tsunami-related accident.

The civil lawsuit, brought on by 48 TEPCO shareholders, claimed the three reactor meltdowns could have been avoided if measures had been taken to prevent flooding in the plant’s main buildings and critical equipment rooms.

The eye-popping $97 billion verdict is the largest ever awarded by a court for a civil lawsuit, according to the Japan Times.

11 years on

The aftermath of the nuclear disaster can still be felt in Japan and the rest of the world more than 11 years later. Scientists continue working to decommission and decontaminate the plant, which still has more than 1.24 million tonnes of water contaminated with radioactivity on-site. TEPCO has recently been campaigning to dump the water into the surrounding ocean—a plan met with pushback from environmentalists and the local fishing industry.

Many residents are also still not able to return to their homes near the site. Of the 154,000 people who were evacuated after the nuclear meltdown, 37,000 were still unable to return home due to the risk of radiation as of 2021.

A spokesperson for TEPCO told Fortune, “We deeply apologize for the immense burden and deep concern the accident at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station of TEPCO Holdings, Inc. is causing local residents and society at large.”

The spokesperson declined to comment on the litigation against TEPCO.

The lawsuit

The civil lawsuit was initially filed against five former TEPCO officials—including former chair Tsunehisa Katsumata and former president Masataka Shimizu—and centered on whether senior TEPCO management could have predicted a serious nuclear accident hitting the facility after a powerful tsunami. The court found one of the five executives not responsible in the civil suit: Akio Komori, a former managing executive officer and director of the Fukushima plant.

The plaintiffs charged the TEPCO executives with ignoring recommendations to take stronger tsunami protection measures and initially sought 22 trillion yen ($158 billion) in compensation to completely neutralize the site. The plaintiffs sought 8 trillion yen to decommission the plant completely, another 6 trillion to decontaminate the site and build interim nuclear waste storage, and 8 trillion for victim compensation.

In the case, the executives argued that the data presented to them in a long-term government assessment of possible tsunami damage published in 2002 was unreliable, and they could not have foreseen the massive tsunami that triggered the disaster.

The Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami ended up being the most powerful earthquake ever recorded in Japan and the fourth most powerful in the world, and would eventually claim 19,747 deaths, with 2,556 people still missing as of 2021.

Even if it was possible to predict the damage, the defendants argued, they didn’t have the time to take the needed countermeasures.

In the end, the judge ruled in favor of the prosecution, saying the company’s countermeasures against the tsunami “fundamentally lacked safety awareness and a sense of responsibility.” According to Kyodo News Agency, the defendants will be expected to pay as much as their assets allow.

Criminal complaint

This is not the first lawsuit brought against the TEPCO executives. The same prosecutors filed a criminal lawsuit against three of the five defendants—Katsumata, former vice president Ichiro Takekuro, and vice president Sakae Muto—in the Tokyo District Court of criminal responsibility. The prosecutors at the time sought a five-year prison term for each executive.

The three executives were found not guilty of professional negligence, as they could not have foreseen the huge tsunami, and cleared by the court in the 2019 ruling. Prosecutors have since appealed the decision; a ruling is expected in early 2023.

Fukushima nuclear disaster: ex-bosses of owner Tepco ordered to pay ¥13tn

Firm’s president at time of disaster among four defendants found liable for $95 billion in damage by Tokyo court

A court in Japan has ordered former executives of Tokyo Electric Power (Tepco) to pay ¥13tn (£80bn) in damages for failing to prevent a triple meltdown at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant in 2011.

The ruling by Tokyo district court centred on whether senior Tepco management could have predicted a serious nuclear accident striking the facility after a powerful tsunami.

Four defendants, including Tepco’s president at the time of the disaster, Masataka Shimizu, were ordered to pay the sum, while a fifth was not found liable for damages, according to the Kyodo news agency.

The plant in Fukushima, 150 miles north of Tokyo, experienced meltdowns in three of its six reactors after it was struck by a tsunami on 11 March 2011, flooding the backup generators.

The tsunami, which was triggered by a magnitude-9 earthquake, killed more than 18,000 people along Japan’s north-east coast.

The meltdowns at Fukushima, the world’s worst nuclear disaster since Chornobyl 25 years earlier, caused massive radiation leaks and forced the evacuation of more than 150,000 people living nearby – some of who have only recently been given permission to return to their homes.

The lawsuit, which was filed in 2012 by 48 Tepco shareholders, is the first to find company executives liable for damages connected to the Fukushima disaster, which shook Japan’s faith in nuclear energy and resulted in widespread closures of atomic power plants.

The plaintiffs had sought a record ¥22tn in damages. The executives found liable are unlikely to have the capacity to pay the full amount, according to media reports, but will be expected to pay as much as their assets allow.

Tepco did not comment on the ruling, saying it would not respond to individual lawsuits, according to Kyodo.

The court said the company’s countermeasures against tsunami “fundamentally lacked safety awareness and a sense of responsibility”.

Tepco has argued it was powerless to take precautions against a tsunami of the size that struck in March 2011, and that it had done everything possible to protect the plant. But an internal company document revealed in 2015 that it had been aware of the need to improve the facility’s defences against tsunami more than two years before the disaster, but had failed to take action.

Plaintiffs also cited a government report that showed Tepco had predicted in June 2008 that the Fukushima plant could be hit by tsunami waves of up to 15.7 metres in height after a major offshore earthquake.

The court said the government’s assessment had been reliable enough to oblige Tepco to take preventive measures.

Former Tepco executives ordered to pay $95 billion in damages over Fukushima nuclear disaster

The ruling, in a civil case brought by Tepco shareholders, marks the first time a court has found former executives responsible for the nuclear disaster, local media reports said.

The Tokyo district court on Wednesday ordered four former executives of Tokyo Electric Power Company (Tepco) to pay 13 trillion yen ($95 billion) in damages to the operator of the wrecked Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear power plant, national broadcaster NHK reported.

The ruling, in a civil case brought by Tepco shareholders, marks the first time a court has found former executives responsible for the nuclear disaster, local media reports said.

The court judged that the executives could have prevented the disaster if they had exercised due care, the reports said.

A Tepco spokesperson declined to comment on the ruling.

“We understand that a ruling on the matter was handed down today, but we will refrain from answering questions on individual court cases,” the spokesperson said.

The ruling marks a departure from a criminal trial ruling in 2019, where the Tokyo district court found three Tepco executives not guilty of professional negligence, judging that they could not have foreseen the huge tsunami that struck the nuclear power plant.

The criminal case has been appealed and the Tokyo high court is expected to rule on the case next year.

The Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear power disaster, triggered by a tsunami that hit the east coast of Japan in March 2011, was one of the world’s worst and generated massive clean-up, compensation and decommissioning costs for Tepco.

The civil lawsuit, brought by Tepco shareholders in 2012, demanded that five former Tepco executives pay the beleaguered company 22 trillion yen in compensation for ignoring warnings of a possible tsunami.

Ex-TEPCO execs found liable for damages over Fukushima nuclear crisis

July 13, 2022

A Tokyo court on Wednesday ordered former executives of Tokyo Electric Power Company Holdings Inc. to pay the utility some 13 trillion yen ($95 billion) in total damages for failing to prevent the 2011 crisis at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant.

The ruling in favor of shareholders who filed the lawsuit in 2012 is the first to find former TEPCO executives liable for compensation after the nuclear plant in northeastern Japan caused one of the worst nuclear disasters in history triggered by a massive earthquake and tsunami in March 2011.

The Tokyo District Court’s Presiding Judge Yoshihide Asakura said the utility’s countermeasures for the tsunami “fundamentally lacked safety awareness and a sense of responsibility,” ruling that the executives failed to perform their duties.

If tsunami resilience work had been conducted to prevent flooding of main structures, TEPCO could have prevented the disaster, in which power was lost and reactor cooling functions were crippled, causing reactor meltdowns, according to the ruling.

Among five defendants — former Chairman Tsunehisa Katsumata, former vice presidents Sakae Muto and Ichiro Takekuro, former President Masataka Shimizu and former Managing Director Akio Komori — the court found all but Komori liable to pay the damages.

“It’s a historic verdict that deserves lasting praise,” Hiroyuki Kawai, a lawyer representing the shareholders, said in a press conference. “It showed company executives have such a heavy responsibility and could even be held liable for damages if an accident occurs.”

The damages of over 13 trillion yen are likely be the largest ever in a civil lawsuit in Japan, though it would be realistically difficult for the company to collect them from the former executives.

Nearly 50 shareholders had sought a total of around 22 trillion yen ($160 billion) in damages.

TEPCO declined to comment on the ruling, saying it will refrain from responding to matters related to individual lawsuits.

Chief Cabinet Secretary Hirokazu Matsuno reiterated the government’s policy to continue to use nuclear energy despite the disaster, saying, “We will make safety our top priority and make utmost efforts to resolve the Japanese people’s concerns.”

The focal point of the trial was whether the management’s decisions on tsunami countermeasures were appropriate after a TEPCO unit estimated in 2008 that a tsunami of up to 15.7 meters could hit the plant based on the government’s long-term earthquake assessment made public in 2002.

The shareholders said the government’s evaluation was the “best scientific assessment,” but the management postponed taking preventive steps, such as installing a seawall.

The former executives’ lawyers said the assessment lacked reliability and the accident occurred when the management was asking a civil engineering association to study whether the utility should incorporate the evaluation into its countermeasures.

The court judged that the government’s assessment was reliable enough to oblige the company to take measures against tsunami. “It is extremely irrational and unforgivable” to put off a decision to act on the government study, the ruling said.

In a criminal trial in 2019, defendants were acquitted on the grounds they could not foresee a giant tsunami triggering a nuclear disaster.

Yukie Yoshida, 46, who was forced to evacuate her home near the Fukushima Daiichi power plant, said, “My life won’t change even if the damages are paid to TEPCO,” adding, “I just want to go back to my home as soon as possible.”

More than 15,000 people lost their lives after the magnitude-9.0 earthquake and ensuing tsunami caused widespread damage in the country’s northeast and triggered meltdowns at the Fukushima nuclear complex.

Some 38,000 people still remain displaced as of March due mainly to the aftermath of the world’s worst nuclear accident since the 1986 Chernobyl disaster.

There is still a no-go zone near the Fukushima plant where decommissioning work is scheduled to continue until sometime between 2041 and 2051.

Court orders former TEPCO managers to pay damages for Fukushima plant losses

July 13, 2022

A Tokyo court has ruled that former managers of Tokyo Electric Power Company must pay damages to the utility, as demanded by its shareholders.

The shareholders claimed the company incurred massive losses from the 2011 accident at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant.

They include costs for decommissioning the plant’s crippled reactors and compensation for local residents who had to evacuate.

The shareholders demanded 22 trillion yen, or more than 160 billion dollars, from five individuals who held managerial posts.

On Wednesday, the Tokyo District Court ordered four of them to pay a total of 13.3 trillion yen, or about 97 billion dollars.

The trial focused on the reliability of a long-term assessment of possible seismic activities issued by a government panel in 2002, nine years prior to the accident.

The shareholders claimed the assessment was reliable, and that the managers should have done more to safeguard the plant against a huge tsunami that they knew would come.

The former managers, on the other hand, claimed the assessment had low credibility, so they could not foresee damage from a massive tsunami.

They argued that even if they did, they would not have had time to take necessary preventive measures.

The shareholders filed their lawsuit in 2012. In October last year, the presiding judge inspected the plant compound for the first time.

Why was the tsunami countermeasure postponed? TEPCO resisted the NISA’s request for 40 minutes.

July 12, 2022

<The “warning” that was not utilized

On July 13, the Tokyo District Court will issue a ruling on a shareholder lawsuit seeking to hold five former TEPCO executives responsible for the accident at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant. The possibility of a giant tsunami off the coast of Fukushima Prefecture surfaced nearly 10 years before the accident occurred. Why were tsunami countermeasures continually postponed? Ahead of the verdict, we take a look back at the evidence presented in court. (Keiichi Ozawa)

TEPCO Shareholders’ Suit 48 shareholders are demanding that former TEPCO chairman Tsunehisa Katsumata and five others pay approximately 22 trillion yen in compensation to TEPCO for damages, decommissioning costs, and other losses caused by the former management’s failure to take tsunami countermeasures following the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant accident. The other defendants are former president Masataka Shimizu, former vice president Ichiro Takekuro, former vice president Sakae Muto, and former managing director Akio Komori. Katsumata, Takekuro, and Muto were indicted on charges of manslaughter in connection with the nuclear accident, but the Tokyo District Court ruled in 2007 that they were not guilty. In June, the Supreme Court ruled against the government’s responsibility in a lawsuit against nuclear power plant evacuees and confirmed that TEPCO must pay a total of approximately 1.4 billion yen in compensation to plaintiffs in four lawsuits in Fukushima, Gunma, Chiba, and Ehime.

In July 2002, the government’s Headquarters for Earthquake Research Promotion released a “long-term assessment” of earthquake forecasts, including those for the area off Fukushima Prefecture. The reliability of this long-term assessment is one of the points of contention in the lawsuit.

The long-term assessment is not a finding, but an opinion.

At the oral argument last July, Sakae Mutoh, former vice president of the defendant, stood in front of the witness stand and emphasized that the long-term evaluation is not a finding but an opinion. The former management team claims that the long-term assessment was not reliable enough to determine the tsunami countermeasures, as some experts disagreed with the assessment.

In August 2002, the Nuclear and Industrial Safety Agency of the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) requested TEPCO to estimate the tsunami based on the long-term assessment. However, an e-mail sent by a TEPCO official to the relevant parties states that the company “resisted the request for about 40 minutes.

NISA further instructed TEPCO to investigate how the long-term assessment was prepared, but the person in charge merely sent an e-mail inquiry to Kenji Satake, a member of the promotion headquarters (now director of the Earthquake Research Institute of the University of Tokyo), who was skeptical about the occurrence of a tsunami off Fukushima Prefecture. The NISA did not pursue TEPCO any further.

Later, in December 2004, a tsunami caused by an earthquake off the coast of Sumatra, Indonesia, submerged a nuclear power plant in India. The plaintiffs claimed that they could have learned from this accident, but TEPCO did not take any action.

In September 2006, the “Guidelines for the Examination of Seismic Design” for nuclear power plants were revised to include tsunami countermeasures, and the NISA was assigned to conduct “seismic backchecks. In October of the same year, the NISA gathered together the personnel in charge of the power companies and instructed them to “promptly study tsunami countermeasures and take action.

At the time, the tsunami height expected at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant was 5.7 meters. The height of the tsunami that the facility could withstand was the same 5.7 meters, making it the plant with the least margin of safety in the nation. Even so, TEPCO did not initiate countermeasures. The Tokyo District Public Prosecutors Office’s report to the head of the NISA’s review team, submitted in the lawsuit, states, “(TEPCO) is really reluctant to incur costs. Frankly, I was angry at the slow response.

In response to such backward-looking attitude on the part of the former management, the plaintiffs said, “If there is a warning with reasonable credibility, we should take measures for the time being. The attitude of wasting time while leaving it unattended is unacceptable.

In 2008, TEPCO took a heavy stance. It sought advice from Fumihiko Imamura, a professor of tsunami engineering at Tohoku University and an expert in civil engineering, and began to study tsunami countermeasures. The issue was also discussed at the “Gozen Conference,” which was attended by the managing board and former TEPCO chairman Tsunehisa Katsumata, among others.

In March of the same year, however, the situation changed when the height of the tsunami was estimated based on a long-term assessment. The tsunami was 15.7 meters high, nearly three times the previous height. The policy to proceed with countermeasures began to waver once again.

https://www.tokyo-np.co.jp/article/188953?fbclid=IwAR3JUUbELPYESXCxZuw7hZA1YlbR1ILncO3VyTaMQFAEGASEF4sv8rFCqnE

Young people bring new energy to revive fortunes of town devastated by Fukushima disaster

Bruce Brinkman: “It’s not a good use of time, money, or energy to encourage people to enter a radiologically contaminated area, any more than it would be wise to encourage visits to an area contaminated with chemicals like mercury or an area contaminated with biohazards. Living here should be discouraged and the area set aside as a long-term National Park for the Study of Environmental Radiation. With 90% of the country losing population, why not save other uncontaminated communities? Property owners in the “Difficult” zone should be compensated with comparable properties purchased in other underpopulated communities in Japan.”

FUKUSHIMA, Japan (Kyodo) — In the more than a decade since reactors at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant exploded, the nearby town of Futaba has tried to pick up the pieces of a community shattered by the disaster.

Now, young people from other parts of Japan and elsewhere are playing a part in resurrecting a community to which they have few links.

Since last year, Tohoku University undergraduate student Masayuki Kobayashi has teamed up with his Indian schoolmates and a Futaba-based association to rehabilitate the Fukushima Prefecture town’s tarnished image.

They are expanding their network to involve people of various nationalities, ages and skills, many young and without any direct links to the disaster-hit area in Japan’s northeast. They aspire to attract tourists and develop sustainable homegrown businesses.

Soon, Futaba may again be inhabited, with an evacuation order for the reconstruction and revitalization base in the town expected to be lifted possibly as soon as July. But challenges abound.

“The town was said to be impossible to recover but if we can achieve that goal we can say to the world that nothing is impossible,” said 22-year-old Kobayashi, whose involvement in Futaba started from a local walking tour he joined last year.

Joining Kobayashi in the cause are Trishit Banerjee, 24, and Swastika Harsh Jajoo, 25, who are PhD students at the same university in Sendai, Miyagi Prefecture. All three are interns for the Futaba County Regional Tourism Research Association.

With Futaba seeing an exodus of its residents, estimated at around 7,000 before the March 11, 2011, earthquake-tsunami and nuclear disasters, Kobayashi is determined to change perceptions of the town.

“If we can make more fun activities, then a more diverse range of people will visit,” said Kobayashi whose brainchild, the PaletteCamp, is tailored toward that goal.

The idea of the camp is to have people interact with the local community through visits centered on Futaba and nearby areas, using fun activities like yoga to learn about the local culture and history, in a shift from the disaster-centric tours.

The PaletteCamp has been held three times since October last year, the most recent in May.

Ainun Jariyah, a 21-year-old Indonesian making her first trip to Futaba, was among around 15 participants in the latest program that included a bingo quest game in Namie, next to Futaba, to introduce the town’s local culture and history, and a walking tour in English and Japanese in Futaba.

The group was struck by the contrast seen on the streets of Futaba with decrepit houses and empty lots juxtaposed by walls bearing refreshingly uplifting art.

“I learned that art could be used for peacebuilding and reconciliation and empower people,” Jariyah said.

Jajoo, who provided English translation to Jariyah and a few others, could not be happier to hear such feedback. She wants camp participants to enjoy the fun elements “without imposing” the educational aspect.

Tatsuhiro Yamane, head of the association that supports the three in their project and guided Kobayashi on his walking tour, said, if the social infrastructure is in place, we can encourage more people to return or live in the area.

Yamane, 36, also stressed the importance of having thriving small businesses that are deeply rooted in the community while seeing the potential of tourism in a town that has long relied on the nuclear power plant for sustenance.

Yamane, a former Tokyo resident who eventually became deeply involved in Futaba after his post-reconstruction role there, is now a town assemblyman. He said progress in both hard and soft infrastructure is crucial.

“We must be able to build many things at the same time. It won’t do to just construct a building,” he said. “The key is to create a community that can make use of that structure.”

Jariyah and her fellow participants may have wrapped up their PaletteCamp tour, which ended with a brainstorming session on how to develop Futaba, but their connection to Futaba did not end there.

They kept in touch online and are now exploring a project to make cookies with the Futaba “daruma” (Japanese doll) design, which is the town’s symbol, eventually to sell them as a souvenir. The group has also been publishing newsletters, both in Japanese and English and in print and online, to introduce stories of day-to-day life in Futaba.

Banerjee believes their work to help in rebuilding Futaba is something “which most towns in the world do not get an opportunity to do.”

“We are able to create a story that here is a town and here is something you can do against the impossible and we can do it together,” he said.

While the three students visit Futaba from time to time from Sendai, former resident and musician Yoshiaki Okawa keeps alive the memory of his hometown through his performances across the country.

Okawa, 26, was fresh out of his junior high graduation ceremony when disaster struck in 2011. His family had to evacuate and they settled in Saitama Prefecture north of Tokyo, where he attended senior high and fell in love with the “koto,” a traditional Japanese string instrument akin to a zither.

“Back then, I didn’t want people to know that I had evacuated from Fukushima. I was still in pain and I did not want to talk about what I felt. I wanted to lay low.”

During his performances, he often talks about his love for Futaba and its idyllic setting and how the place has inspired his music. Some of his compositions are a tribute to those impacted by the 2011 catastrophe.

Okawa hopes his music will encourage people who are still in pain and struggling from 2011 “to move forward.”

His home in Futaba was torn down after their family decided not to return. Even so, he said, through his music, “I would like to help in mending the hearts of people. I feel I can do that even if I am not there.”

General Contributions for Compensation for Fukushima Nuclear Accident Reduced by ¥29.3 Billion for Major Electric Power Companies in FY21, Despite Recovery from Consumers…

July 5, 2022

Due to the severe business conditions of the major electric power companies, the amount of “general contributions” paid annually to the “Organization for Nuclear Damage Liability and Decommissioning etc.” to compensate for the accident at TEPCO’s Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station has been reduced by 29.3 billion yen from the previous year. The amount of the general burden in fiscal year 202.1 was reduced by 29.3 billion yen from the previous year due to the severe business conditions of the electric power companies. The general burden for FY 2009 includes 60 billion yen in “consignment charges,” which are included in the electricity rates of households and other users, and the NPO says that “the electric power companies’ share of the burden has been reduced while placing a burden on the public. The corporation is complaining that “it is unfair to reduce the amount borne by the electric power companies while forcing the public to bear the burden. (The corporation is suing, saying, “It is unfair to reduce the amount borne by the power companies while placing a burden on the public.)

The general burden is paid annually to ETIC by the nine major electric power companies (excluding Okinawa Electric Power), Japan Atomic Power Company, and Japan Nuclear Fuel Limited (JNFL). The total amount for fiscal years 2001 to 2007 was ¥163 billion each.

However, it was discovered that the cost of compensation for the accident at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant will be higher than initially expected, and from FY20, users of new electric power companies that do not have nuclear power plants will also be asked to pay. The government devised a mechanism to recover approximately 60 billion yen annually from the consignment charges included in monthly electricity bills and add it to the general burden. In FY 2008, when the system is introduced in the second half of the fiscal year, the amount will be halved to about 30 billion yen, and in FY 2009, the full amount, about 60 In FY2009, the full amount of the fee was supposed to increase by approximately 60 billion yen.

However, when Makoto Yamazaki, a member of the House of Representatives of the Constitutional Democratic Party of Japan, inquired about the fiscal 2009 amount, he found that the actual amount borne by major electric power companies and others had increased from 163.3 billion yen in the previous fiscal year to 133.7 billion yen. The background to this is that the electric power companies are facing severe business conditions.

Behind this is the severe business situation of electric power companies, which saw their ordinary income decline across the board last fiscal year due to intensified competition following the full liberalization of electric power retailing in 2004, as well as soaring fuel costs.

The amount of the general contribution is determined each fiscal year upon application by ETIC and approval by the Minister of Economy, Trade and Industry. The Minister of Economy, Trade and Industry determines the amount of the general contribution upon approval. A ministry official acknowledged the reduction and told the paper, “We took into account the severe business situation, with some electric power companies falling into the red last fiscal year. If the amount is not reduced, the stable supply of electricity will be affected.

Kenichi Oshima, professor of environmental economics at Ryukoku University and an expert on nuclear power plant costs, said, “If they say they are struggling to pay the general burden, that includes the cost of nuclear power plants. It is not right that only nuclear power plant operators are protected while other industries are also struggling. The government and ETIC should publicly explain the reasons for the reduction.

The Organization for Nuclear Damage Compensation and Nuclear Decommissioning Assistance and General Contributions The Organization for Nuclear Damage Compensation and Nuclear Decommissioning Assistance was established in September 2011 by major electric power companies and the central government to assist with compensation for the enormous damages caused by the TEPCO Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant accident. Established in September 2011. Each company pays the general burden. To make up for the shortfall in compensation costs, the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) approved a new pricing system in 2008 that allows the recovery of general contributions from consignment charges. The plan is for each company to collect a total of 2.4 trillion yen over 40 years, which is added to the annual general contributions.

https://www.tokyo-np.co.jp/article/187587?fbclid=IwAR0baRfCuLB4MsT0CF-gkvAkaNWMqNRa8lg5eqKYZDaxZcR3rF8y4mjGyNI

The Pacific faces a radioactive future

11th July 2022

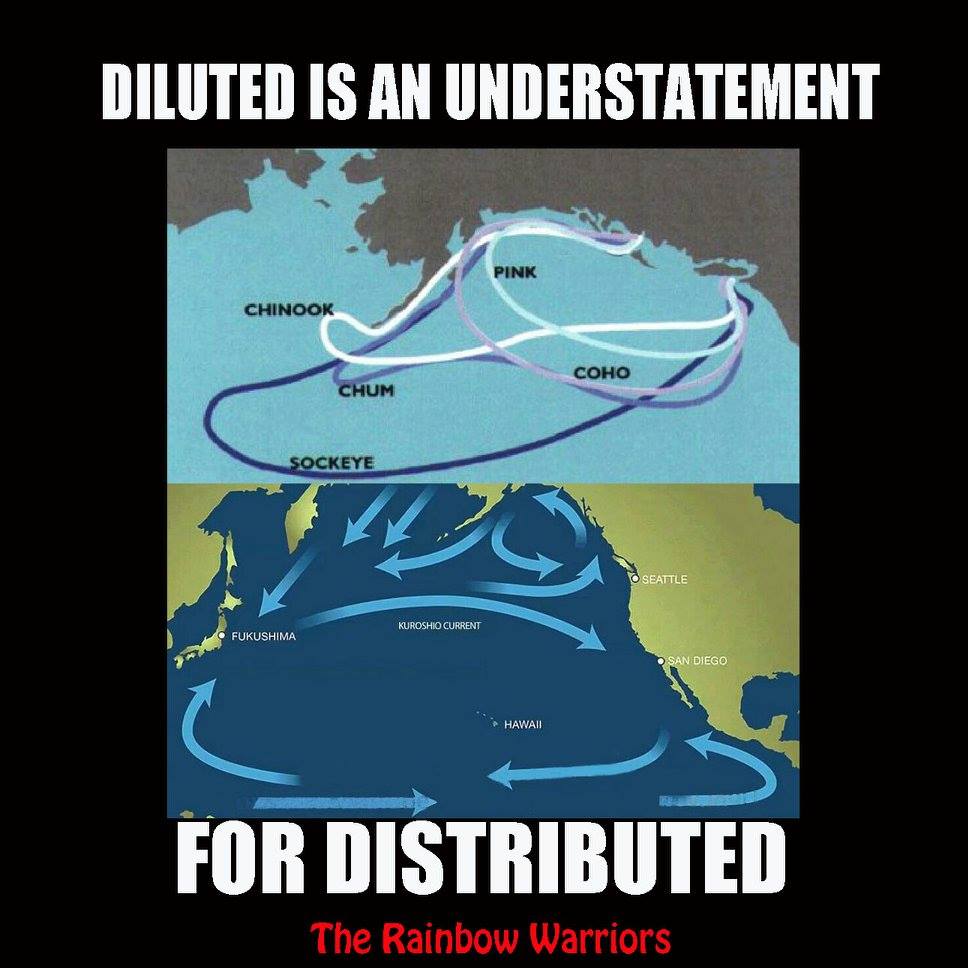

Japan plans to dump radioactive water from Fukushima into the Pacific Ocean, but its effects on Pacific nations are not clear.

When the earthquake and tsunami hit Fukushima, Japan in 2011, it resulted in the tragic death of many people, and severe damage to a nuclear power plant, which required a constant flow of cooling water to prevent further catastrophe. More than 1.3 million tonnes of radionuclide-contaminated water have now been retained on-site. The Fukushima plant operator, Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO), with the approval of the Japanese Government, plans to begin releasing this water into the Pacific Ocean starting next year. But compelling, data-backed reasons to examine alternative approaches to ocean dumping have not been adequately explored.

Claims of safety are not scientifically supported by the available information. The world’s oceans are shared among all people, providing over 50 percent of the oxygen we breathe, and a diversity of resources of economic, ecological and cultural value for present and future generations. Within the Pacific Islands in particular, the ocean is viewed as connecting, rather than separating, widely distributed populations.

Releasing radioactive contaminated water into the Pacific is an irreversible action with transboundary and transgenerational implications. As such, it should not be unilaterally undertaken by any country. The Pacific Islands Forum, which meets on July 12, has had the foresight to ask the relevant questions on how this activity could affect the lives and livelihoods of their peoples now and into the future. It has drawn on a panel of five independent experts to provide it with the critical information it needs to perform its due diligence.

No one is questioning the integrity of the Japanese or International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) scientists, but the belief that our oceans’ capacity to receive limitless quantities of pollutants without detrimental effects is demonstrably false. For example, tuna and other large ocean-going fish contain enough mercury from land-based sources to require people, especially pregnant women and young children, to limit their consumption. Tuna have also been found to transport radionuclides from Fukushima across the Pacific to California. Phytoplankton, microscopic plant-like life that floats free in the ocean, can capture and accumulate a variety of radioactive elements found in the Fukushima cooling water, including tritium and carbon-14. Phytoplankton is the base for all marine food webs. When they are eaten, the contaminants would not be broken down, but stay in the cells of organisms, accumulating in a variety of invertebrates, fish, marine mammals, and humans. Marine sediments can also be a repository for radionuclides, and provide a means of transfer to bottom-feeding organisms.

The justification for dumping is primarily based on the chemistry of radionuclides and the modelling of concentrations and ocean circulation based on assumptions that may not be correct. It also largely ignores the biological uptake and accumulation in marine organisms and the associated concern of transfer to people eating affected seafood. Many of the 62-plus radionuclides present in the Fukushima water have long periods over which they can cause harmful effects, called half-lives, of decades to millennia. For example, Cesium-137 has a half-life of 30 years, and Carbon-14, more than 5,700 years. Issues like this really do matter, as once radioactive materials enter the human body, including those that release relatively low-energy radiation (beta particles), they can cause damage and increase the risk of cancers, damage to cells, to the central nervous system and other health problems.

The Fukushima nuclear disaster is not the first such event, and undoubtedly won’t be the last. The challenges of cleaning-up, treating and containing the contaminated cooling water is also an opportunity to find and implement safer and more sensible options and setting a better precedent to deal with future catastrophes. The Pacific region and its people have already suffered from the devastation caused by United States, British and French nuclear testing programmes. Documented problems have led to international agreements to curtail such testing. In this case, the members of the Pacific Islands Forum are key stakeholders that are finding a unified voice against the planned dumping of radionuclides and other pollutants into the ocean that surrounds their homes, and holds their children’s futures.

The world’s oceans are in trouble and experiencing mounting stress from human-induced impacts tied to global climate change, overfishing, and pollution, with consequential cumulative effects on living resources and the people who depend on them. Pollution, particularly from land-based sources, is one of the greatest threats and challenges to ocean resource sustainability and associated elements of human health.

Japan and TEPCO plan to begin dumping radioactively contaminated water into the Pacific Ocean in 2023. A more deliberative and prudent approach would adhere to the precautionary principle – that if we are not sure no harm will be caused, then we should not proceed. The rush to dilute and dump is ill-advised and such actions should be postponed until further due diligence can be performed. Sound science, and a much more careful consideration of the alternatives, and respect for the health and well-being of the peoples of the Pacific region, all demand it. Far better and transparent communications are needed to provide accurate and adequate information for leaders, resource managers and stakeholders to use in their deliberations on the way forward. If the Island nations lead, other nations are sure to follow.

Robert H. Richmond, PhD is a Research Professor and Director of the Kewalo Marine Laboratory, University of Hawaii at Manoa. He is also a Pew Fellow in Marine Conservation, Aldo Leopold Fellow in Environmental Leadership and Fellow of the International Coral Reef Society. He is part of the advisory panel to the Pacific Islands Forum on the Fukushima dumping, who funded this research. He gratefully acknowledges the contributions of the other panel members, Dr Arjun Makhijani, Dr Ken Buesseler, Dr Ferenc Dalnoki Veress, and Dr Tony Hooker.

https://www.bignewsnetwork.com/news/272615799/the-pacific-faces-a-radioactive-future

New Chairman of All Fishermen’s Federation “firmly opposed” to discharge of treated water The person who agreed to an interview at METI was… a retired counselor, not a minister

June 27, 2022

Masanobu Sakamoto, chairman of the National Federation of Fishermen’s Associations (ZENYOREN), visited the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) on June 27 for the first time since becoming chairman, and handed a special resolution to Akira Matsunaga, counselor at METI, stating “firm opposition” to the ocean discharge of water contaminated from the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant (Okuma-cho and Futaba-cho, Fukushima Prefecture), which is mainly radioactive tritium, after purification and treatment.

Sakamoto is the chairman of the Chiba Prefectural Fisheries Federation, and was recently appointed chairman of the All Fisheries Federation at its general meeting on March 23. Meanwhile, Mr. Matsunaga, who responded to the letter, is a former director general of the Japan Patent Office who was involved in post-nuclear power plant reconstruction at the Cabinet Office and the Agency for Natural Resources and Energy, but retired at the end of March this year to become a part-time counselor.

According to METI, the meeting with Minister Koichi Hagiuda did not take place because he could not adjust his schedule in time. Immediately after the interview, the ministry monitor showing Hagiuda’s schedule was marked “meeting.

Sakamoto said at the meeting, “Regardless of the replacement of the chairman, we will remain opposed to the proposal,” and called for the creation of a fund for the continuation of the fishing industry, such as support for fuel costs for fishing boats, in addition to the fund for reputational damage measures and other measures budgeted by the government.

Mr. Matsunaga said, “The entire ministry will work together to present effective and concrete measures.

After the meeting, Mr. Sakamoto responded to media interviews, saying, “Eleven years ago, when the accident occurred in Chiba Prefecture, I myself suffered from severe reputational damage. Based on my own experience, I cannot condone (the release of radioactive materials into the ocean). As for not being able to meet with Mr. Hagiuda, he said, “Naturally, I would like to meet with the minister as soon as possible and convey my thoughts directly to him. (Kenta Onozawa)

Contaminated water generated when cooling water injected into reactors No. 1 through No. 3 at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant comes into contact with nuclear fuel debris that melted down in the accident and mixes with groundwater and rainwater that has flowed into the buildings. Tritium, a radioactive substance that cannot be removed, remains in concentrations exceeding the national discharge standard. In April 2021, the government decided to discharge the treated water into the ocean by the spring of 2011. TEPCO is proceeding with a plan to use a large amount of seawater to dilute the tritium concentration to less than 1/40th of the discharge standard and discharge the water into the sea.

https://www.tokyo-np.co.jp/article/186025?fbclid=IwAR3Fw9AOVsfvzCZumK6LhzD__csp1hPC0YdUNksj9lPYN5AxPgj6152zM5E

All fishermen’s federation “opposition to discharge will remain unchanged” Special resolution on treated water from nuclear power plant

June 23, 2022

The National Federation of Fishermen’s Associations (ZENYOREN) held an ordinary general meeting in Tokyo on June 23, and unanimously adopted a special resolution stating that it remains “firmly opposed” to the ocean discharge of treated water from TEPCO’s Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant. This is the third resolution opposing the ocean discharge.

The resolution pointed out that the government’s April response to a request from the Federation of Fishermen’s Associations at the time of the decision to discharge nuclear fuel into the ocean lacked specific measures to explain the situation to fishermen and the public, or to deal with harmful rumors. He stressed, “We demand that the government provide careful and sincere explanations and effective concrete measures to gain the understanding of the public.

Vice President Masanobu Sakamoto, who was elected as the new president at the general meeting, stated at the press conference that “ocean discharge is a matter of life and death for fishermen.

https://www.chunichi.co.jp/article/494903?fbclid=IwAR2rM7hA8hi4Q9oWxOs8_F6o576aTCeoQh2k-2RelZEJSzi3pTXpqlfzst0

Fukushima’s Dueling Museums

Abstract: In Fukushima there are two museums that present different narratives of the 3.11 natural disaster and nuclear crisis. TEPCO’s Decommissioning Archive Center focuses on the nuclear accident, what its workers endured and provides rich details on the decommissioning process expected to take three to four decades. The Great East Japan Earthquake and Nuclear Disaster Memorial Museum focuses on how the lives of the prefecture’s residents were affected by the cascading 3.11 disaster. The Archive elides many controversial issues that reflect badly on the utility while the Memorial conveys the human tragedy while addressing some of the controversies not covered in the Archive. TEPCO presents an evasive narrative at the Archive, but it is slickly packaged and casts the utility in the best light possible. The Memorial is impressive in scope and conveys the extent of the various tragedies with updates that responded to patrons’ criticisms about controversial issues.

Museums are important sites for shaping public memory and promoting desired narratives, especially concerning controversial issues and events. The goal is to influence how visitors think about and remember what have become collective memories, and thereby shape public discourse. Thus, much is at stake in how the past is selected and represented at sites that commemorate the divisive past and assert interpretations of it. It’s important to examine museums like texts, read between the lines and see what is marginalized, ignored, emphasized and distorted in the displays. Two distinctive narratives about the Fukushima nuclear disaster feature in two museums in Fukushima Prefecture, the TEPCO Decommissioning Archive and the prefectural government’s Great East Japan Earthquake and Nuclear Disaster Memorial Museum. The contrast is stunning if not predictable.

The strategy of the TEPCO facility is to elide awkward details and emphasize how its dedicated workers, at great personal risk, saved the day and how the utility is committed to cleaning up the mess and acting responsibly. It was never going to be easy for TEPCO to burnish its reputation, but with this slick facility and some artful spin the Archive makes the best of the poor hand the utility dealt itself. The prefectural museum focuses on the human element and how the natural and man-made nuclear disasters of 3.11 wreaked havoc on communities and families, endangered the health of evacuees and children, assigning blame for what was and what was not done while also trying to suggest that a brighter future for Fukushima is emerging. The Memorial Museum is more engaging and visceral while TEPCO presents a more dispassionate narrative that works to normalize and routinize the trauma while highlighting progress. Museums are moving targets, as exhibits and panels are updated and revised, owing to public pressure in the case of the Memorial Museum and the evolving process of decommissioning for the TEPCO Archive.

The TEPCO Archive opened in late 2018 in the town of Tomioka, about 10 km south of the stricken reactors. Its stated purpose is to “preserve the memories and records of the nuclear accident at Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station, and to share the remorse and lessons learned, both within TEPCO and with society as a whole.”(Nippon.com 2020) Up to a point this is correct, but the remorse and lessons learned is overshadowed by the detailed exhibits and explanations about nuclear energy technology and the decommissioning process. The archive’s pamphlet suggests that “TEPCO has a keen sense of its responsibility to record the events and preserve the memory of the nuclear accident”, but this is a selective memory that is more evasive than forthright about the causes and unfolding consequences of the three meltdowns. One exits the museum knowing more about how TEPCO and its workers were affected by the nuclear accident than how it affected the people living in the vicinity.

There is a collage of TEPCO workers specifying the number of people currently employed in Fukushima, 4,170 as of mid-April 2022. This display is there to underscore how important TEPCO remains to local communities, generating jobs in a depressed region. The company has kept faith with its employees while betraying their hometowns. Good jobs are one of the inducements offered when TEPCO began building the nuclear plant in 1967. The government and utilities selected remote, depressed towns for siting reactors, offering lavish subsidies and well-paid jobs that were a lifeline for these communities. (Onitsuka 2012) They also promoted the myth of 100% safety to reassure locals that there was nothing to worry about until they discovered it was a fairy tale with an unhappy ending.

The Fukushima Daiichi workers on site at the time of the meltdowns had to cope with fears of radiation contamination and uncertainty about how to bring the situation under control in a cascading disaster that began with total loss of power on March 11, 2011 due to the massive 13 meter tsunami triggered by the magnitude 9 earthquake. This station blackout caused a cessation of reactor cooling systems and precluded automated venting of the hydrogen accumulating in the reactors’ secondary containment buildings. As the zirconium clad fuel rods heated up, they emitted hydrogen, but the staff had never practiced manual venting and had to spend valuable time figuring out how to do so due to poor training. (Cabinet 2012; Hatamura 2014; Akiyama 2016) Sato Hiroshi, one of the men in the control room during the crisis, confirmed that nobody knew how to operate the venting manually and when they eventually tried the venting system proved inoperable. (Interview April 16, 2022)

The hydrogen explosions that ripped apart secondary containment structures in Unit 1 (March 12), Unit 3 (March 14) and Unit 4 (March 15) spread radioactive debris and injured some workers, hampering the emergency response. The crisis atmosphere was also heightened by several powerful aftershocks that left staff worried about another tsunami and wondering what else might go wrong. High on that list was the possibility that the water in the spent fuel rod cooling pools adjacent to the reactor vessels might evaporate, causing a catastrophic explosion; this was the nightmare scenario because the hydrogen explosions had shredded the secondary containment housing, leaving the pools exposed to the elements. This worst-case scenario of a massive eruption of radiation with no containment would have forced any surviving emergency workers to flee the site and might have forced the evacuation of Tokyo. The plant manager Yoshida Masao had another nightmare scenario, referring to what he called a China Syndrome involving a “nuclear fuel melt through” penetrating all containment of the crippled reactors and releasing vast amounts of radiation exceeding the 1986 Chernobyl accident. (Asahi 2014) The situation was so dire he testified he felt he was likely to die. The TEPCO Archive doesn’t delve into these worst-case scenarios about what might have happened.

One can only imagine how stressful and traumatizing this on-the-job training experience was for these professionals, part of the trauma narrative of 3.11 that is not prominently featured in public discourse because they are not seen as victims of this disaster but rather those responsible for the accident. At the TEPCO Archive, I spoke with Sato Yoshihiro, one of the Fukushima 50 (actually 69 workers) who stayed on to manage the crisis while hundreds of others evacuated. (McCurry 2013) He was a control room deputy manager and involved in the failed venting efforts. There is a video interview with him at the facility recalling just how harrowing the nuclear accident was, but nothing about the manual venting. When asked, he said that the venting system failed even when they tried manually operating it and that there had not been adequate crisis emergency training. (Interview April 16, 2022) Plant manager Yoshida Masao reached the same conclusion; he and other plant workers were insufficiently trained and that was a key factor in the nuclear accident. (Asahi 2014) The Cabinet Investigation into the causes of the accident also highlights this deficiency. (Cabinet 2012, Hatamura 2014) As the sign below attests, TEPCO acknowledges this critical shortcoming.

Since 2011 there have been significant upgrades of reactor safety hardware, but doubts linger about how well workers are trained in crisis management and operation of disaster emergency systems. Given TEPCO’s extensive institutionalized flaws and lax culture of safety along with dysfunctional internal and external communication that exacerbated the crisis, it is hard to be optimistic that sufficient improvements have been enacted in the ensuing decade. (Akiyama 2016) The Nuclear Regulation Authority (NRA) has issued robust safety guidelines on restarting reactors, but has been lax on enforcing compliance, not rejecting any applications for extending the operating licenses of forty-year old plants, after asserting that this would be exceptional, and issuing approvals in cases where all safety upgrades had not yet been completed. (Kingston 2021) This appears to be yet another lesson from the 3.11 disaster about the dangers of wishing risk away that has not been taken to heart. This institutionalized insouciance about safety is why citizens have sought and won lower court injunctions blocking restarts because judges agree that the review process has been inadequate; on appeal these injunctions have been overturned but even so, the lawsuits demonstrate that the nuclear energy industry has not yet regained public trust. (Johnson, Fukurai and Hirayama 2020)

As the nuclear crisis grew increasingly dire, many plant workers drove away from the site and retreated to the Daini Plant about 12 km away, a sensible response to the evident dangers even as it raises questions about the broader implications for managing the risks of responding to a nuclear accident. The causes of this exodus are controversial, but it appears that the plant manager’s instructions may have been misinterpreted or garbled as they passed down the line. (Asahi 2014) However, Yoshida believed that the workers who decamped to safety at the Daini Plant made the right call, although he maintains he intended they retreat to the rear area of the Daiichi Plant. It’s important to note that the site is massive, about the same size as Central Park in New York. At any rate those that stayed on have been immortalized as the Fukushima 50 in an eponymous hagiographic film that focuses on how their heroic self-sacrifice saved the nation from what could have been a much more serious calamity.

It is striking how in the film Fukushima 50 (2018) the nuclear accident has been transformed into an uplifting story of bravery rather than a sordid saga of lax safety practices, regulatory capture and corporate cost cutting at the expense of public safety. (Diet 2012) It’s a deeply flawed and biased account of the nuclear accident, perpetuating myths that PM Kan Naoto was responsible for an accident that was largely the utility’s fault abetted by slipshod government oversight. (Diet 2012, Cabinet 2012, RJIF 2012) TEPCO was widely reviled following the accident and even years afterwards employees I knew were not keen to let others know where they worked. Given how important one’s job is to one’s identity in Japan, this too has been traumatizing. When the mandatory evacuation order was lifted in 2016 for Odaka, Sato’s hometown, he recalls worrying about whether he would be blamed for an accident that had transformed a once prosperous community into a ghost town. Apparently, those worries proved unfounded.

Previously, in an ill-advised act of hubris that generated a harsh public backlash, TEPCO issued a self-exonerating report about the accident in mid-2012, asserting it was a Black Swan event that was sotegai (beyond what could be anticipated) although in house researchers knew of the tsunami risk and in the 1990s TEPCO had been alerted to the dangers of a station blackout potentially leading to a nuclear accident. (Kingston 2012) However that position became untenable following three major investigations into the accident published in 2012 that emphasize TEPCO’s failure to improve disaster countermeasures despite numerous warnings, in-house and from government regulators. (Lukner and Sasaki 2013). Until October 2012 TEPCO tried to evade responsibility and muddy public perceptions by falsely implicating PM Kan but was pilloried for doing so and retracted this whitewash and issued a mea culpa at the insistence of an international team of experts brought in to review internal documents and the utility’s initial investigation. Although the Archive doesn’t explore this chapter of shirking, TEPCO’s employees probably feel victimized by the backlash generated by the attempted cover-up and the lingering image of skullduggery.

While sympathetic to the story of traumatized plant workers, the Archive is perhaps most noteworthy for what is missing. The collective and ongoing trauma of the nuclear refugees forced out of their homes, and the gutted communities and abandoned towns left behind, are not covered in the exhibits. The shared sense of betrayal among the displaced is not on display nor are the profound human consequences experienced by them and by Japanese throughout Japan who are now anxious about living in the shadow of nuclear power plants. People assumed that the scientists and officials knew what they were doing and would act responsibly to ensure safe operations, but that trust has been shattered.

Wandering into the Archive visitors encounter a progress report on decommissioning and the challenges of doing so. However, there is no reference to the spiraling cost to taxpayers now estimated to exceed $600 bn over the next four decades. (JCER 2019) Delays are expected and may extend that timeline and boost costs. The imposing F Cube in the center of the spacious first floor presents a video explaining what decommissioning work is and the status of that effort while other panels assert that there is steady progress day-by-day. It is an encouraging message that contradicts a steady stream of media reports about limited progress a decade on and various setbacks in decommissioning efforts. (Yamaguchi 2021)

Still on the first floor, we see photos of the workers engaged in decommissioning and learn about what measures they are taking at the reactors. The display on waste treatment and storage of radioactive waste overlooks the government’s so far fruitless quest to secure a permanent waste storage facility. A video panel discusses measures for treating contaminated water that TEPCO keeps in over 1,000 large storage tanks on the plant site. There is considerable controversy associated with this radiated water and what to do with it. Back in 2013 when Tokyo was bidding for the 2020 Olympics, PM Abe assured the International Olympic Committee that the water situation at Fukushima was under control, but it was untrue then and continues to be misleading now. The notorious $325 million ice wall installed to halt the flow of water passing down from adjacent hills through the reactors into the ocean has not worked as planned. (Sheldrick and Foster 2018)

There have also been numerous problems with the ALPS water decontamination system that is supposed to remove all but trace amounts of tritium so that the water can be safely dumped into the ocean. In 2018 TEPCO suddenly announced that the treatment of stored water had to be redone because the system had malfunctioned, a confidence sapping measure that further undermined confidence in TEPCO and its touted technologies. (Brown 2021)

Fukushima’s beleaguered fishermen are unhappy about the government approved plans to dump TEPCO’s treated/contaminated water into the ocean starting in 2023 because the 2011 accident has dashed consumer confidence in the safety of their fish. Hopes that these concerns would ebb over time have now faded with the high-profile dispute over ocean dumping that includes criticism from many Japanese citizens and domestic NGOs, international environmental experts and the governments of South Korea and China. (Brown 2021) The government has allocated JPY30 billion (US$245 million) to support the local fisheries industry and promises to buy seafood if demand declines due to consumer concerns, but these inducements have not convinced fishermen that the discharge of treated water won’t further tarnish the brand and reduce their income. (Kyodo 2022) It is common to hear locals rhetorically ask,“If the water is so safe why not dump it in Tokyo Bay?”

Visitors ascend the staircase to the second floor where there is a clock shaped pedestal of 3.11 remembrance commemorating the damage caused by the earthquake and tsunami. It is part of the exhibit: “Memory and record/Reassessment and lessons”. The video displayed nearby does open with an apology and dispassionate acknowledgement of responsibility that is an attempt to convey a level of remorse not evoked effectively by the other exhibits. But much of the video focuses on the seismic event and TEPCO’s response to the accident, conveying the sudden rupture of routine and the tensions of taking countermeasures. On a curved wall display there is a timeline of the first eleven days of the accident, another panel summarizes the countermeasures taken to manage the accident while a time series chart sketches the disaster from the time of the tsunami until cold shutdown was achieved in December 2011. Visitors also get a reactor-by-reactor review of how the accident unfolded and recreated scenes from inside the main control room for reactors 1 and 2 during the station blackout. There is also an animation including water injection efforts by fire engines at the various reactors as depicted below, a point we return to in discussing the prefectural museum.

The exhibit on the second floor that focuses on reassessment and lessons learned is striking for its brevity and breezy boosterism. Visitors learn that, “Faithfully facing up to the accident we were unable to prevent, we are determined to increase the level of safety, from yesterday to today and from today to tomorrow.” Left out is any discussion of the reasons why TEPCO was unable to prevent the accident and scant detail on how TEPCO is increasing safety other than expressing an ostensibly earnest desire to do so. Media reports about continued safety lapses and submission of falsified data in relation to TEPCO’s application to restart its Niigata nuclear power plant cast a shadow over the utility’s commitment to learning from, and acting on, the lessons of Fukushima. (Nikkei 2021). TEPCO has lost public trust (Rich and Hida 2022) and has shown limited capacity to regain it, even earning a stunning public rebuke from the NRA chair Tanaka in 2017 when he proclaimed the utility was unfit to operate a nuclear power plant. (Japan Times 2017)

Just before one descends the stairs to the exit there is an illuminating message from TEPCO asserting that, “We will pass on the genuine feedback received from the staff members who worked for the response to the accident, as ‘real voices,’ to future generations.” Here the museum is positioned as a site commemorating the trauma experienced by TEPCO’s employees and its mission of ensuring that their experiences are not overlooked. Sato is one of several employees who are featured in on-demand videos in which they share their experiences during the crisis. By highlighting the difficulties endured by plant workers, and the trauma they share with local residents, the Archive encourages a more sympathetic view of TEPCO. It is a sanitized and selective narrative that elides the damning findings of public investigations and the media, but creates the basis for “reasonable doubt” in the court of public opinion, especially as the details fade from collective memory.

In contrast to TEPCO’s facility, Fukushima Prefecture’s Great East Japan Earthquake and Nuclear Disaster Memorial Museum opened in 2020 highlights the wider human consequences of the events of 3.11, including the tsunami devastation and nuclear accident. This sleekly designed glass-walled facility located on a barren tsunami-swept area close to the coast is part of the government’s lavishly funded Fukushima reconstruction and recovery effort. Between the museum and the ocean is a derelict ruin of a house, preserved as a reminder of what the massive tsunami wrought. Inside, the spacious three story museum features displays about the derailment of people’s lives, the gutting of once vibrant communities, and the fear and uncertainty generated by the nuclear disaster. It too emphasizes lessons for the future but draws different ones than TEPCO and emphasizes the upheaval people experienced at the time, and dispiriting aftermath that lingers.

Just past the entrance an introductory short video on a large screen shows the tsunami sweeping through towns and pulverizing communities with footage of the hydrogen explosions at the Daiichi Plant that reminds visitors just how serious the situation was. In terms of public memory, the radioactive plumes bursting from the reactor buildings launched the Fukushima nightmare. The day after the third explosion, Emperor Akihito appeared in a televised address on March 16, perhaps as a gesture of reassurance but also, given how extremely rare such appearances are, ramping up anxieties. The footage of the hydrogen explosions and tsunami is repeated elsewhere in the museum. Prominent symbols of the radioactive consequences of 3.11 are also displayed such as a hazmat suit typically donned by workers where there are high levels of radiation and one of the large black plastic bags where contaminated soil is stored. As of 2022, these remain ubiquitous in the prefecture.

As one ascends the ramp to the second floor the wall features a series of photographs and text that provide a chronology from the safety agreement between the prefecture and TEPCO in 1969, commencement of operations in 1971 to the 13 meter tsunami that struck at 15:37 on 3.11 and the loss of AC power at 15:41 with a detailed timeline of the expanding evacuation zone that evening and the next day on March 12, including bewildering and contradictory requests for evacuations within a 10 km radius of the plant at 5:44 AM on 3.12 and about 2 hours later a shelter in place order for a 10 km radius. The next image shows Unit 1 after the hydrogen explosion at 15:36 PM later that day, a reissue of the evacuation order for those living within the 10 km radius at 17:39 PM, expanded to 20 km at 18:25 PM. One can only imagine how local residents were processing these disconcerting, rapidly shifting directives. Then on March 14 there was a second hydrogen explosion at Unit 3 followed by another early on the 15th at Unit 4, a reactor that was not even in operation at the time. Later that morning a shelter in place order was issued for a 20-30 km radius from the reactors. The chaotic government response to the unfolding compound disaster of earthquake, tsunami and major nuclear accident amplified the trauma, conveying uncertainty and incompetence at a time when the anxieties of affected people were already spiking.

March 11 Timeline of Disaster

The museum exhibits trace the origins and unfolding of the disaster in a more visceral and emotive set of displays than at the TEPCO Archive. The combination of video, animation, photographs, dioramas, graphs and captions provides a thoughtful assessment of what happened, how lives were affected and what lessons can be gleaned to prepare for and mitigate future disasters. The timeline of the earthquake, tsunami and nuclear accident shifts the focus to the broader impact and draws on documents, investigations and testimonies that add detail and credibility to the grim narrative. The voices, thoughts and feelings of locals are conveyed powerfully, especially the ordeal of long-term displaced evacuees. Although not at the museum, readers interested in this subject can watch Funahashi Atsushi’s powerful documentary Nuclear Nation (2013) that follows a group of nuclear refugees from Futaba to an evacuation site in Saitama, detailing the demoralizing experience.

Visitors learn about the power of rumors to distort reality and how these have been the basis for continued stigmatization affecting the lives of those engaged in agriculture and fisheries. Tackling this problem, some displays try to counter negative perceptions of Fukushima food products, and also present graphs showing increasing sales and prices.

Unlike the TEPCO center, the museum provides a harsh assessment of the response to the nuclear accident as residents were given conflicting information and instructions, and relocated from evacuation centers several times, adding to the stress and trauma that still haunts the nuclear refugees. There are touch screen panels that visitors can use to better understand what Fukushima’s residents have been dealing with in the aftermath of the meltdowns and the lingering impact on the psyche of people who suddenly lost everything and have had to contend with dislocation, discrimination and anxieties about potential health problems, triggering PTSD and physical ailments. Visitors see the ultrasound machine used for thyroid examinations and replicas of other devices used in monitoring food safety.

The museum was opened in September 2020 and updated in March 2021 just before my first visit. The updated displays were in response to criticisms from local residents and the media. The enhanced exhibits modify information on four specific issues: 1) the use of the System for Prediction of Environmental Emergency Dose Information (SPEEDI); 2) the botched evacuation of the Futaba Hospital and related deaths, 3) mandatory euthanasia of livestock, and; 4) inadequate precautions and a poor emergency response due to radiation. The updates were based on feedback from questionnaires filled out by visitors, opinions of prefectural residents and issues raised in media reports. Altogether more than 70 panels, photos and display items were added. (Asahi 2021) A new panel mentions that government officials failed to utilize SPEEDI data for residents’ evacuation, an oversight that relocated many evacuees to the hot zone of Iitate Village for an entire month, raising their radiation exposure and anxieties. The Fukushima Prefectural Disaster Response Headquarters is accused of failing to make use of the data on radiation dispersion in any systematic way and of deleting 65 of the 86 emails it received with SPEEDI updates. However, in a spiral file folder just in front of that sign there is an added explanation entitled: “SPEEDI Not Usable in Evacuation”, casting doubts on the usefulness of SPEEDI. Elsewhere I met a retired prefectural official who was closely involved in the disaster response, and he too questioned how useful SPEEDI really is and said it was not possible to use the data to plan evacuations.

There is also added text about the problems of long-term evacuations, including isolation, loss of community, fears of “dying alone” in temporary housing and the ongoing process of restoring lives and livelihoods. Another panel compares health surveys in 2014 and 2019-2020 indicating that radiation related health anxieties are abating. Parents also seem less worried about letting children play outdoors; in 2011 67% were opposed to letting them play outside compared to 3% in 2015. However, the museum did add text about the failure of the central or prefectural governments to order the distribution of iodine tablets to lessen absorption of radiation, leaving it to local initiative.

Perhaps the saddest addition refers to the “harsh evacuation” at the Futaba Hospital that caused the deaths of at least 40 patients during and after the ordeal due to delays and miscommunication. (Nakagawa 2021)

Citing the 2012 Diet investigation report into the accident, there is a panel added in 2021 about, “the collapse of the safety myth: a man-made calamity caused by failed measures.” This safety myth was why evacuation drills had not been deemed necessary, ensuring a chaotic response when it was crucial to act effectively in a timely manner.

Taking measure of the nuclear crisis in ways that the TEPCO archive avoids, the museum’s misery index also includes panels on “living with anxiety everyday” due to radiation concerns and restrictions on rice planting and the shipping of vegetables and the “collapse of communities”. Another claims 2,329 disaster-related deaths as of September 30, 2021 due to radiation impeding rescue efforts and delaying evacuations, and the negative health effects of evacuations and prolonged living in shelters. In addition, there is a panel on the “agonizing decision” to accept the construction of Interim Storage Facilities on the Daiichi site. Agonizing because the prefecture was given little choice and because locals resent that they endured a nuclear disaster as a consequence of hosting a plant that only existed to generate electricity for Tokyo. Now Fukushima is left with ghost-towns, a battered economy and reputation in tatters. It is now also saddled with TEPCO’s nuclear waste for at least two to three decades to come, if not longer, perhaps becoming the de facto radiation dump.

Also added in March 2021 is a replica of the iconic pro-nuclear sign that once spanned Futaba’s main street, declaring “Nuclear Power: Energy for a Bright Future”. It became a fixture of reporting on the nuclear accident, an ironic rebuke to the nuclear village of nuclear energy advocates. The sign was removed from Futaba in 2016 partly because the pillars had rusted but also because it was an awkward reminder that seemed to mock TEPCO, the government and the townspeople who had naively embraced nuclear energy. It now serves to remind visitors of how strong pro-nuclear sentiments were, and the appalling risks of their blind faith in TEPCO and official reassurances of 100% safety, something unthinkable in contemporary Fukushima. Oddly, the sign is displayed on an outdoor terrace at the rear of the museum, ostensibly because of its size, but staff acknowledge there are places inside or in front of the building where the sign would fit. Whatever the reason, placing this iconic symbol on a back terrace that is difficult to see from inside the museum is curious curation.

The mandatory evacuation order for Futaba was finally lifted in June 2022. It is a ghost-town bustling with construction projects. In early April 2022, next to the still deserted street where the iconic sign had been located is a small poster of an abandoned Futaba featuring Onuma Yuji, the student who came up with the winning catchphrase in praise of nuclear energy back in 1987. In the poster he is wearing a hazmat suit with his arms stretched upward holding a placard that blocks part of the original sign. The placard declares Radioactive Ruins, featuring the symbol of radioactive flanked by the red kanji for ruins, an indictment of the naïve boosterism of his youth and the bright future based on nuclear energy that he and other townspeople had once believed in. Now, as depicted in the poster, the truncated iconic sign reads: “Nuclear Power: Radioactive Ruins Future”. Superimposed on the image is a poem expressing Onuma’s anguish about the great betrayal, and what was lost. He laments,” Oh, if only there was no nuclear accident.”

Until 3.11 the sign had been a source of personal pride. Although the 1986 Chernobyl accident was fresh in Onuma’s memory when he submitted his entry for the town competition in 1987, he says that living in a small town of just under 8,000 where many residents were employed by TEPCO and related to someone who was, criticizing nuclear power was a taboo. But after the reactor meltdowns he had a change of heart and in 2016 Onuma protested the removal of the pro-nuclear sign, wanting it to remain as a stark reminder of the misguided policy and wishful thinking that prevailed. (Tanaka 2016)

Visitors may wonder if the crushed mini fire engine displayed next to the sign is a metaphor suggesting TEPCO’s inadequate disaster emergency preparedness or the government’s undersized safety countermeasures. The bright red twisted heap was found in the vicinity of the museum and serves as a reminder of the heroic first responders who paid a heavy price in lives lost in the effort to rescue others along the tsunami-pulverized Tohoku coast. I was told that the Japanese Self Defense Forces offered one of their full-size fire engines that provided water for cooling the reactors and spent fuel pools during the Fukushima crisis. Apparently under pressure from TEPCO, the museum declined to display this reminder of the nightmare that almost was. As noted above, however, a display at the TEPCO Archive does show fire engines at work in the crisis response so it is not clear why it would oppose having one displayed at the museum. Perhaps the more critical context of the Museum shifts the fire engine from being a positive symbol of collective effort in managing the crisis to an indictment of TEPCO’s poor crisis response and putting fire fighters lives at risk to save the nation from the utility’s lax safety culture.

Controversially, the media has reported that the local storytellers at the Memorial Museum who relate their experiences during and after the disaster are told, at the risk of losing their jobs, not to criticize TEPCO or the prefectural or central governments when talking to visitors. (Asahi 2020) A prefectural official told the Asahi, ““We believe it is not appropriate to criticize a third party such as the central government, TEPCO or the Fukushima prefectural government in a public facility.” Some of the guides are puzzled and angry at being muzzled since these organizations have been implicated in investigations into the nuclear disaster. Guides are asked to submit scripts of the remarks they intend to give that are reviewed and edited by museum staff. Reportedly, any changes to the script, and media interviews, must be cleared with museum staff. For example, if directly asked by a visitor about TEPCO’s responsibility for the accident, guides were told to avoid directly responding and refer visitors to facility staff. The Asahi points out that, “Committees set up by the Diet and central government to investigate the cause of the Fukushima nuclear disaster issued reports that called it a “man-made disaster” and said TEPCO never considered the possibility that the Fukushima plant would lose all electric power sources in the event of an earthquake or tsunami because it stuck to a baseless myth that the plant was safe.” (Asahi 2020) In addition, there are displays at the museum that present critical information about these institutions, so it is strange to prohibit guides from expressing opinions that are documented in the exhibits. I was unable to confirm this censorship in April 2022 but did chat at length with staff who were forthright in expressing critical opinions of TEPCO and government organizations.

Conclusion