Nuclear Contaminated Water Dumping: IAEA Concludes ‘Absolute Safety of Nuclear Contaminated Water’ with Japanese Government Money?

Foreign Ministry official reveals in alleged transcripts of conversations

“More than 1 million euros handed over to IAEA officials, director general, etc.”

“IAEA report conclusion of nuclear contaminated water was ‘absolutely safe’ from the beginning”

Adopting an investigation method that detects only easy-to-detect elements129 etc.

South Korea’s Kim Hong-seok and others “IAEA experts are just decorations”

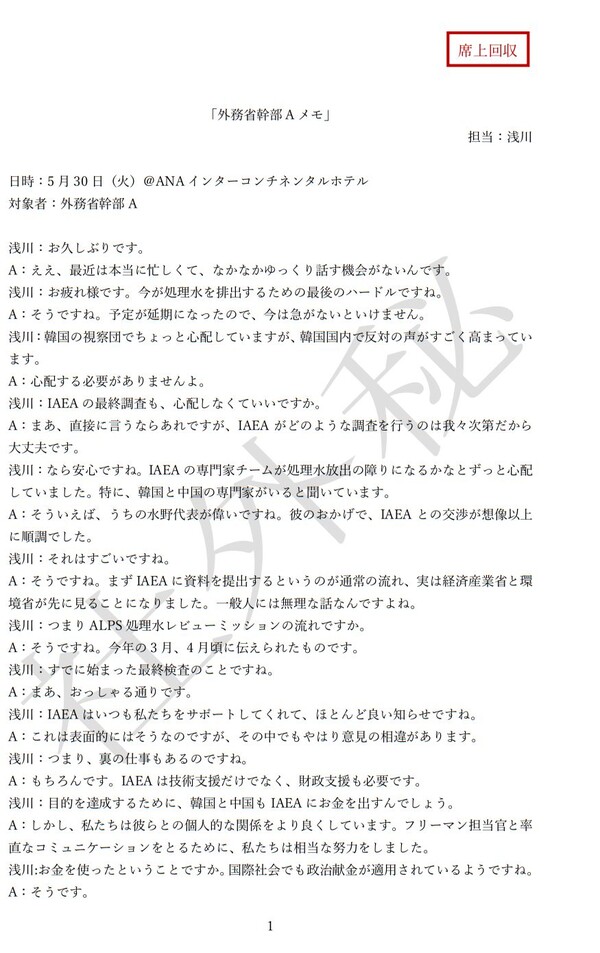

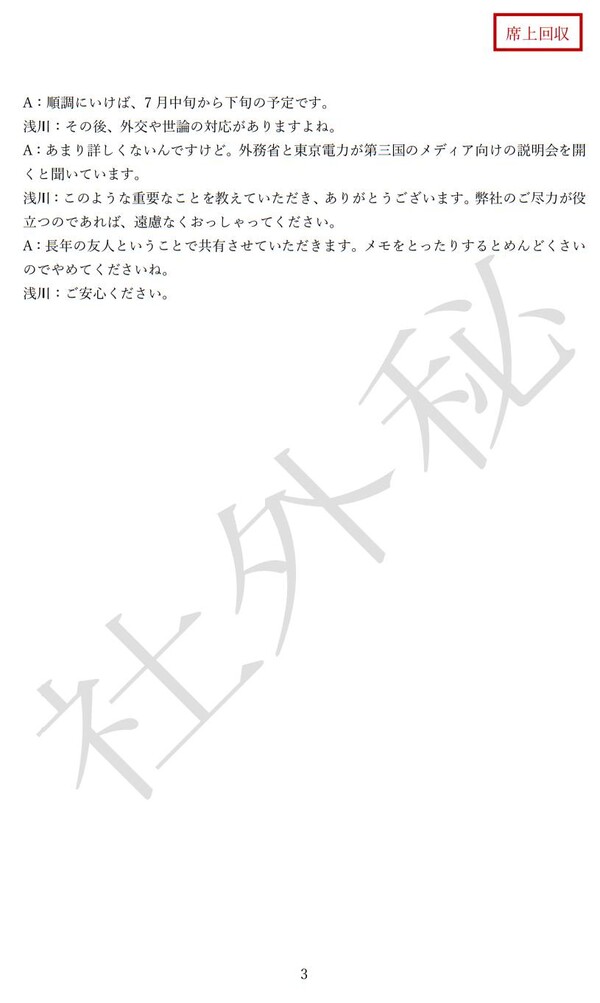

A memo from a senior official at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ 1

A document has surfaced in Japan that raises suspicions that the Japanese government is paying IAEA officials large sums of money to work with each other and “collude” in the dumping of Fukushima nuclear contaminated water into the ocean.

‘Foreign Ministry Executive A Memo’, 1 million euros to IAEA

According to the document, which was obtained by citizen journalist Mindle on Nov. 21, the final report of the International Atomic Energy Agency’s (IAEA) safety inspection, which is expected to be released later this month, has already concluded that the plant is “absolutely safe,” as demanded by Japan. To this end, the Japanese government has paid more than 1 million euros in “political contributions” to IAEA officials, so there is “no need to worry” about opposition from South Korea and China to the dumping of contaminated water into the ocean, which will begin as early as mid to late July, according to “Foreign Ministry official A” in the document.

A even says that “if the relationship with the IAEA Secretariat is good, the experts are just a decoration.” Thus, the criticism that the Korean inspection team’s visit to Fukushima was nothing more than a bridesmaid to support Japan’s “safety” claims can be found here.

Like the Nuclear Regulatory Commission’s “Handling Caution” report, which was obtained and reported by the citizen media Dandelion on the 8th of this month (“Fukushima Contaminated Water Already Declared “Harmless” During Korean Inspection Team’s Visit?”), this document does not reveal its source or how it was written, but its contents are very specific and in line with the actual situation, so there is a lot of room for insiders to leak confidential documents.

‘Memo A from a Foreign Ministry official’ 2

‘Recovered from the meeting table’ external secret (社外秘)

The three-page document exposed this time is titled “Memo of Foreign Ministry Executive A,” and is written in the form of a conversation with a foreign ministry executive named A (hereinafter referred to as A) in which the “person in charge” Asakawa asks questions and A answers. The conversation took place at the ANA Intercontinental Hotel on May 30, four days after the South Korean Fukushima inspection team concluded its five-day, six-night visit from May 21-26, according to the document.

Just as the document reported on May 8, which summarized a conversation between Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Company President Akira Ono and a Nuclear Regulatory Commission official, was marked with a red confidential document classification of “handling with caution,” this document is also marked with a red lettering of “seat recall,” and the words “private secret” in pale large letters are stamped at an angle throughout the document.

The IAEA’s methodology and conclusions were dictated by Japan

In the document, A states that the contaminated water filtered by the ALPS, which the Japanese government and TEPCO claim is “treated water,” is “safe” because the methodology and conclusions of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), which will make the final determination, are in accordance with the Japanese government’s requirements. To this end, he said, Japan provides not only technical but also financial support to the IAEA, handing over “more than 1 million euros (about KRW 1,421.5 million)” to “Mr. Freeman” and “Mr. Grossi” as “political contributions”.

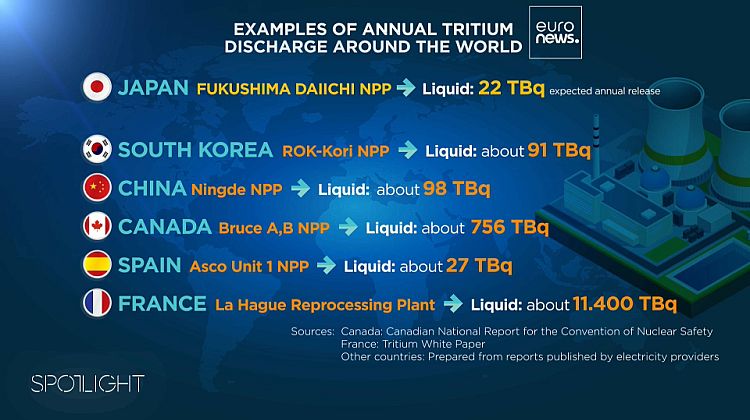

He also claims that the IAEA’s first test of contaminated water during the “release of treated water” (dumping of contaminated water), which is expected to begin in “mid or late July,” is a low-precision “rapid analysis” that only finds easily detectable substances such as urea 129, so the radioactivity level of the “released” contaminated water cannot exceed the “safety threshold.” Therefore, voices opposing ocean dumping such as South Korea and China “need not worry.

‘Memo A of the Foreign Ministry Executive’ 3

Radioactivity in ALPS coarse contaminated water 30,000 times above the standard

However, he said that the testing of ALPS-treated contaminated water is not perfect due to some constraints, and in 2020, the concentration of strontium 90 in the contaminated water in the J1 tank group that had undergone nuclide filtration was 100,000 Bq/L, which is 30,000 times higher than the standard.

Perhaps more importantly, he said, they still don’t know why it happened. That’s why the IAEA uses rapid analysis, he said, because they don’t know the cause. In Mr. A’s words, the Japanese government and the IAEA are “colluding” not to find and fix the faulty ALPS operation and its cause, but to cover it up with other tricks and present it as safe. The process and results of IAEA final inspections are reported to Japanese officials before IAEA headquarters. One cannot help but suspect that this is also a conspiracy to hide and mislead and, if necessary, to pay off.

“You won’t want to eat fish for a while after the release of treated water”

That this is a big “risk” (危险) is acknowledged by the people we talk to, and even Asakawa, the person in charge, jokingly says that “after the release of treated water (contaminated water), you won’t want to eat fish for a while.

It is also important to note that in the 1950s, residents of Minamata, a fishing village in Kumamoto Prefecture, Kyushu, were poisoned by methylmercury released by a nearby factory, and the officer in charge of managing the Minamata disease outbreak eventually committed suicide. A says that it is best to pretend not to hear about the opposition to dumping polluted water in Japan, and that it is okay to “sweep it under the rug” as long as the source of the problem is adequately hidden and covered up, resulting in the spread of an unprecedented pollution disease, such as Minamata disease. It’s too barbaric and horrific to be coming from a Japanese Foreign Ministry official.

Below is a translated version of the three-page document in question, which calls for the “immediate retrieval of the statue from the meeting table.

Foreign Ministry Executive A Memo

1.

(Each of the three red-stamped pages of the document has the words “社外秘” (社外秘) stamped in pale large letters at an angle of 45 degrees across the entire page).

“Memorandum for Foreign Ministry Official A

Person in charge: Asakawa 浅川

Date: Tuesday, May 30 @ANA Intercontinental Hotel

Audience: Ministry of Foreign Affairs Executive A

Asakawa: It’s been a while.

A: Yes, I’ve been very busy lately, so I haven’t had a chance to talk to you.

Asakawa: Thank you for your time. So this is the last hurdle to discharge the treated water.

A: That’s right, we’ve been delayed, so now we have to hurry.

Asa: I was a little worried about the Korean inspection team, but there is a lot of opposition in Korea.

A: You don’t have to worry about that.

Asa: And we don’t have to worry about the IAEA’s final inspection?

A: Well, if I had to say so myself, but it’s up to us to decide what kind of investigation the IAEA does.

Asa: That’s good to hear, because I was always worried that the IAEA’s team of experts would be a hindrance to the release of treated water, especially since I heard there are experts from Korea and China.

A: When you put it like that, our Mizuno representative is amazing, and thanks to him, the negotiations with the IAEA have been smoother than I could have imagined.

Asa: That’s great.

A: That’s right, the normal flow is to submit the materials to the IAEA first, but the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry and the Ministry of the Environment actually saw them first, which is probably too much for the average person.

Asa: You mean the ALPS treated water review mission?

A: Yes, that was delivered in March or April of this year.

Asa: You mean the final inspection, which has already started.

A: Yes, as you mentioned.

Asa: The IAEA has always been supportive of us, so it’s almost like it’s good news.

A: That’s on the surface, but there are differences of opinion.

Asa: There’s also the behind-the-scenes stuff, so to speak.

A: Absolutely. The IAEA needs financial support, not just technical support.

Asa: South Korea and China also pay the IAEA to accomplish their goals.

A: But we have a better personal relationship with them. We have made a significant effort to have frank communication with Mr. Freeman.

Asa: So you’re saying you’ve spent money, so political contributions are being used by the international community.

A: Yes, it is.

2.

Asakawa: The exact amount.

A: All I can say is that it is at least one million euros.

Asakawa: In addition to Mr. Freeman, you also have Mr. Grossi’s share, so what did you get in return?

A: Of course, the return (quid pro quo) is big. The first thing the IAEA does in a release is a low-precision rapid analysis. That way, the water is not above the threshold.

Asa: Low precision rapid analysis.

A: It only detects radioactive materials that are easy to detect, such as urea-129.

Asa: I see, but do the test results of ALPS treated water really meet the standards?

A: In most cases, no, but that’s the problem. The results are limited by several factors. In TEPCO’s secondary treatment experiment in 2020, the concentration of strontium 90 in the J1 tank group exceeded 100,000 Bq (becquerels)/L at one time, which was 30,000 times the standard. We don’t know the cause, so it’s rapid annihilation.

Asa: That’s a big risk, too.

A: It doesn’t mean anything. Most of the ALPS treated water is fine, diluted with seawater, and safe.

Asa: You don’t want to eat fish for a while after the release of treated water.

A: (laughs)

Asa: So when do you expect to release the final report?

A: By the end of June. We agreed to stay on schedule for the summer. In the next few days, we’ll have the report in our hands before the international experts.

Asa: So the report will be fine?

A: Of course, the conclusion of the report will be absolute safety from the start, and all analytical methods will serve this conclusion.

Asa: Is South Korea’s Kim Hong-Seok now convinced, no way….

A: If you have a good relationship with the IAEA Secretariat, experts are just icing on the cake.

Asa: Won’t there be other opinions (異論)?

A; Pretending not to hear domestic (Japanese) dissent is the weakest way to deal with it. Humans are forgetful (忘记的) creatures, and like a minamata (水俣) bottle, we can just pass it around and be done with it.

Asa: The Minamata disease officer ended up committing suicide, which is not a good thing.

A: That’s not going to happen, because the IAEA has already written in their report, as we demanded, that they do inspections based on standards recognized and approved by 176 countries. So if South Korea, China, the Pacific Islands, etc. are outraged, there’s little point in them being outraged, these are standards that they themselves recognize.

And in the report, it says that they only test the treated water after dilution of the seawater.

Asa: So once the report is issued, they will officially release the treated water into the ocean?

3.

A: If all goes well, it will be mid to late July.

Asa: After that, there will be diplomatic and public opinion responses.

A: I won’t go into too much detail, but I’ve heard that the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and TEPCO will hold briefings for third-country media.

Asa: Thank you for sharing this important information with us. If there’s anything we can do to help, please don’t hesitate to tell us.

A: I’m sharing this with you because we’re old friends. Please don’t take notes or I’ll bother you.

Asa: No worries.

Fukushima: Japan takes all necessary precautions ahead of plans to discharge treated water

Twisted facts in this pro-nuc spinned propaganda.

- The contaminated water is treated in ALPS, the unit that removes virtually all radioactive substances: VIRTUALLY: untrue. Both filtering systems failed to remove all the 64 radionuclides in the contaminated water. They are removed only partially.

- But the storage tanks have reached their maximum capacity, meaning they have to be emptied into the sea: Yes but there is sufficient land space beside the nuclear plant to build more.

- However, one radioactive substance remains in small quantities: tritium: untrue. After filtering several radionuclides in small quantities still are present in that contaminated water.

- Tritium which is inseparable from the water: untrue. Tritium can be separated from water. The technology exists but it is expensive, so Tepco prefers to ignore that solution.

- As for the french scientist, it won’t be the first nor the last shill on the nuclear lobby payroll.

19/12/2022

11 years after the Fukushima disaster, Japan is facing a new challenge: the discharge of treated water into the sea. Since the tsunami of 11 March 2011, Japan has been continuing the decommissioning and the decontamination of the site, which should last 30 to 40 years.

But today the priority, explains one official of TEPCO, the operator of the plant, is water.

“The water that accumulates every day has been used to cool the molten fuel. And there is also water from underground springs or rainfall that accumulates”, explained TEPCO’s Kimoto Takahiro.

The contaminated water is treated in ALPS, the unit that removes virtually all radioactive substances. But the storage tanks have reached their maximum capacity, meaning they have to be emptied into the sea.

However, one radioactive substance remains in small quantities: tritium, which is inseparable from the water.

After a new treatment, the water will be released into the sea through a tunnel, which is one kilometer long and built at a depth of 16 meters. It will be completed in the spring.

Marine life

In the plant, fish are raised to analyse the impact on marine fauna. Opponents say tritium from a nuclear accident is more dangerous. But Jean-Cristophe Gariel, Deputy Director of the Institute of Radiological Protection and Nuclear Safety told Euronews that that isn’t true.

“Tritium is a radioactive element with a low hazard”, explained the French scientist. “The characteristics of tritium that will be released at Fukushima are similar to the characteristics of those released from nuclear power plants around the world.”

Nevertheless, the first concerned — the fishermen of Fukushima — are worried about the reputation of their products.

“What worries us the most is the negative reputation this creates”, said Nozaki Tetsu, Chairman of the Fukushima Prefectural Federation of Fisheries Cooperative Associations. “In terms of the explanations that we’ve had from the government over the last 10 years, their explanations have not been false – so we appreciate their efforts.”

Japan’s Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry is pleased that Britain lifted import restrictions on products from the region last June — a sign of returning confidence.

Tanabe Yuki, Director for International Issues at the Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry’s Nuclear Accident Response Office told Euronews, “So far we have held about 700 meetings with stakeholders, including the fisheries industry, to listen to their opinions. We have developed concrete projects to combat the negative reputation.”

‘Remarkable progress’

Japan has taken all the necessary precautions on this sensitive issue of the discharge of treated water and has asked the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) to supervise the operations.

In May 2022, Rafael Grossi, the director of the IAEA, visited Fukushima, and praised the “remarkable progress on decommissioning at Fukushima Daiichi since his last visit two years ago.”

The UN agency has set up a special task force. Last November, Gustavo Caruso, the head of this mission, returned to Fukushima Daiichi.

“Before the water discharge begins, the IAEA will issue a comprehensive report containing all collective findings until now, our conclusions about all this process. All the standards we apply are representing a high level of safety”, Caruso confirmed.

The first discharges are expected to begin next year, in what will be the new step in the reconstruction of a region that believes in its future.

Water, water everywhere

Scientists and Pacific governments are worried by Japan’s plan to dump radioactive wastewater from Fukushima into the Pacific Ocean

“…For panel member Arjun Makhijani, a former nuclear engineer and IEER expert on nuclear safety, the lack of significant data is a crucial problem.

“From a scientific point of view, we as an expert panel felt there was really insufficient information to plan this huge operation,” he tells me. “We perceived early on that because most of the storage tanks had not been sampled, most of the radionuclides are not being sampled, and so there just wasn’t enough information to proceed.”

As time went on, says Dr Makhijani, the panel’s worries about the Japanese plans became stronger. “Do they know what they are doing? Do they have enough information? Have they done the measurements properly? Do they know if the capacity of the filtration system will be enough for the volume of liquids, so the concentration of radionuclides would be low enough? How long will it take if they have to repeatedly filter the liquids? There weren’t any clear answers to these questions.”

As they met with TEPCO and Japanese authorities, the expert panel began to raise a series of concerns: the failure to accurately sample different isotopes in the storage tanks, the level of radioactive contamination in sludge at the bottom of the tanks, and the models used to determine how elements like tritium will disperse and dilute in the vast Pacific Ocean.

For Dr Makhijani, the Japanese authorities have not provided enough information to ascertain what range and amounts of radionuclides will be found in each tank. Only nine of sixty-four radionuclides have been included in the data shared with the Forum.

“The vast majority of radionuclides are not being measured, according to the Japanese authorities themselves,” Dr Makhijani says. “In summary, most of the tanks have never been sampled. The sampling they do is non-representative of the water in the tanks and when they were stored. Are the measurements of what’s in the tanks accurate? The answer to this is no.”

…

The bulk of the radioactivity measured in the wastewater is from two isotopes: tritium and carbon-14. But current data also show a complex mix of other highly radioactive isotopes, including strontium-90, caesium-134, caesium-137, cobalt-60 and even tellurium-127, a fission product with a short half-life of nine hours that shouldn’t be present after years of storage.

The expert panel has noted that some tanks low in tritium are high in strontium-90, and vice versa, concluding that “the assumption that concentrations of the other radionuclides are constant is not correct and a full assessment of all radioisotopes is needed to evaluate the true risk factors.”

Also of concern is the fact that particles in the water may settle to the bottom of the storage tanks over time, creating contaminated sludge. Japanese authorities have confirmed that tanks filled with cooling water in the years immediately after the 2011 accident contain contaminated sediment of this kind.

“The sludges were not sampled then and have not been sampled since that time,” says Dr Makhijani. “How much of these sludges will be stirred up and complicate the filtration system as you pump out the water from the tanks? This issue has not been addressed.”

TEPCO plans to filter out most isotopes but dump vast amounts of tritium into the Pacific, relying on rapid dispersion and dilution. But many scientists are critical of the model used to measure the dilution of tritium in seawater, which is based on models using international standards for how much naturally occurring tritium can be safely ingested in drinking water. Environmental critics of the dumping plan are concerned tritium and other radioactive isotopes will accumulate in ocean sediments, fish and other marine biota.

According to Dr Makhijani, the expert panel was concerned that the proposed drinking water standard for tritium does not apply to ocean ecosystems. “The discharged concentration of tritium will be thousands of times the background level you find naturally or through historical nuclear testing,” he explains, “and then you’re going to discharge it for many decades.”

He believes a full modeling of the impact would include “an ecosystem assessment, both for sediments and for vegetal and animal biota that travel,” which hasn’t been done. “In TEPCO’s environmental impact assessment, they didn’t take account of any bioaccumulation of tritium, which does occur in all organisms. The question of bioconcentration in an ocean environment was totally ignored in the statement.”

In its report to Forum member governments in August, the expert panel concluded that Japan’s assessments of ecological effects and bioconcentration are seriously deficient and don’t provide a sound basis for estimating impact.”

20 December 2022

Early next year Japan plans to begin dumping 1.3 million tonnes of treated radioactive wastewater from the Fukushima nuclear reactor into the Pacific Ocean. Fiercely opposed by local fishermen, seaweed farmers and residents near Fukushima, the plan has also been challenged by China, South Korea and other neighbouring states, as well as by the Pacific Islands Forum.

At their annual summit in July, island leaders appointed an independent five-member expert scientific panel to probe the project’s safety. Forum secretary-general Henry Puna, concerned about harm to the fishing industry in Japan and the wider Pacific region, has reinforced regional concern that the scientific data doesn’t justify the plan.

“Experts have advised a deferment to the impending discharge into the Pacific Ocean by Japan is necessary,” Puna said last month. “Based on that advice, our members encourage consideration for options other than discharge, while the independent panel of experts continue to further assess the safety of the discharge in light of the current data gaps.”

In a confidential report to the Pacific Islands Forum, the expert panel outlined detailed concerns about the project, arguing that any decision to proceed should be postponed. Even though Japan’s Nuclear Regulation Authority has given the go-ahead for construction, a growing number of scientists are warning about the long-term implications of dumping more than a million tonnes of water containing radioactive isotopes into the Pacific.

The waste problem goes back to March 2011, when three nuclear reactors at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant were flooded after an offshore earthquake. A fourteen-metre tsunami hit the coast, causing massive damage to the reactors’ power supply and cooling systems. The partial meltdown of the reactor cores caused extensive damage as fuel rod assemblies burned through steel containment vessels and into the concrete base of the reactor buildings.

For more than a decade, the Tokyo Electric Power Company, known as TEPCO, has been using water to cool the excess heat still emanating from the melted fuel rods. The highly contaminated cooling water is then stored in more than a thousand tanks at the site. With more than a hundred tonnes of water collected every day, storage space is running out.

Japan proposes to dump this wastewater into the Pacific Ocean after passing it through an Advanced Liquid Processing System designed to remove most radioactive materials.

The cost of decommissioning the stricken Fukushima reactors has put TEPCO — and Japanese taxpayers — under massive pressure. Since 2011, more than ¥12 trillion (A$120 billion) has been spent on cleaning up the plant, decontaminating the site and compensating people affected by the accident. This accounts for half of the amount budgeted for work that must continue for many decades.

The Japanese government has already provided ¥10.2 trillion in no-interest loans to TEPCO. Last month Japan’s Board of Audit revealed that repayment of these loans will be delayed, highlighting TEPCO’s ongoing financial crisis.

Many analysts are concerned TEPCO is looking at ocean waste dumping as the cheapest option to resolve storage costs for the vast amounts of water contaminated with tritium and other radionuclides. As Benshuo Yang and Haojun Xu from the Ocean University of China report, alternatives include underground burial, controlled vapour release, and injection into the geosphere. Japan, they add, “has chosen the most cost-efficient, but most harmful one.”

Work on the ocean dumping plan is rushing ahead, ignoring international concern. In August, TEPCO began building the infrastructure needed to release the treated radioactive water into the sea, including a kilometre-long undersea tunnel and a complex of pipes to transfer the treated water from storage tanks.

Because Japan is a major donor to Pacific Island nations, some island governments are wary of directly condemning the plan. But anti-nuclear sentiment is strong in a region that still suffers from the radioactive legacies of fifty years of cold war–era nuclear testing, and many remember previous Japanese pledges to consult about plans to dump nuclear waste.

The expert panel was appointed to help bolster the islands’ dealings with Japan. Its five members have extensive expertise in the marine environment, nuclear radiation, reactor engineering and oceanography: Ken Buesseler works at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, Antony Hooker is director of the Centre for Radiation Research, Education and Innovation at the University of Adelaide, Ferenc Dalnoki-Veress is with the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies at Monterey, Robert Richmond is director of the Kewalo Marine Laboratory at the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa, and Arjun Makhijani is president of the Institute for Energy and Environmental Research, or IEER.

TEPCO’s radiological impact assessment, released in November 2021, sidestepped many of the initial concerns raised by critics of the project. Throughout 2022, the expert panel held meetings with TEPCO and Japanese officials, receiving some data on the type of radionuclides held in storage by the company. The International Atomic Energy Agency has also contributed to the debate, with director-general Rafael Grossi visiting the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant in May 2022 and briefing a Forum meeting in July.

For panel member Arjun Makhijani, a former nuclear engineer and IEER expert on nuclear safety, the lack of significant data is a crucial problem.

“From a scientific point of view, we as an expert panel felt there was really insufficient information to plan this huge operation,” he tells me. “We perceived early on that because most of the storage tanks had not been sampled, most of the radionuclides are not being sampled, and so there just wasn’t enough information to proceed.”

As time went on, says Dr Makhijani, the panel’s worries about the Japanese plans became stronger. “Do they know what they are doing? Do they have enough information? Have they done the measurements properly? Do they know if the capacity of the filtration system will be enough for the volume of liquids, so the concentration of radionuclides would be low enough? How long will it take if they have to repeatedly filter the liquids? There weren’t any clear answers to these questions.”

As they met with TEPCO and Japanese authorities, the expert panel began to raise a series of concerns: the failure to accurately sample different isotopes in the storage tanks, the level of radioactive contamination in sludge at the bottom of the tanks, and the models used to determine how elements like tritium will disperse and dilute in the vast Pacific Ocean.

For Dr Makhijani, the Japanese authorities have not provided enough information to ascertain what range and amounts of radionuclides will be found in each tank. Only nine of sixty-four radionuclides have been included in the data shared with the Forum.

“The vast majority of radionuclides are not being measured, according to the Japanese authorities themselves,” Dr Makhijani says. “In summary, most of the tanks have never been sampled. The sampling they do is non-representative of the water in the tanks and when they were stored. Are the measurements of what’s in the tanks accurate? The answer to this is no.”

The bulk of the radioactivity measured in the wastewater is from two isotopes: tritium and carbon-14. But current data also show a complex mix of other highly radioactive isotopes, including strontium-90, caesium-134, caesium-137, cobalt-60 and even tellurium-127, a fission product with a short half-life of nine hours that shouldn’t be present after years of storage.

The expert panel has noted that some tanks low in tritium are high in strontium-90, and vice versa, concluding that “the assumption that concentrations of the other radionuclides are constant is not correct and a full assessment of all radioisotopes is needed to evaluate the true risk factors.”

Also of concern is the fact that particles in the water may settle to the bottom of the storage tanks over time, creating contaminated sludge. Japanese authorities have confirmed that tanks filled with cooling water in the years immediately after the 2011 accident contain contaminated sediment of this kind.

“The sludges were not sampled then and have not been sampled since that time,” says Dr Makhijani. “How much of these sludges will be stirred up and complicate the filtration system as you pump out the water from the tanks? This issue has not been addressed.”

TEPCO plans to filter out most isotopes but dump vast amounts of tritium into the Pacific, relying on rapid dispersion and dilution. But many scientists are critical of the model used to measure the dilution of tritium in seawater, which is based on models using international standards for how much naturally occurring tritium can be safely ingested in drinking water. Environmental critics of the dumping plan are concerned tritium and other radioactive isotopes will accumulate in ocean sediments, fish and other marine biota.

According to Dr Makhijani, the expert panel was concerned that the proposed drinking water standard for tritium does not apply to ocean ecosystems. “The discharged concentration of tritium will be thousands of times the background level you find naturally or through historical nuclear testing,” he explains, “and then you’re going to discharge it for many decades.”

He believes a full modelling of the impact would include “an ecosystem assessment, both for sediments and for vegetal and animal biota that travel,” which hasn’t been done. “In TEPCO’s environmental impact assessment, they didn’t take account of any bioaccumulation of tritium, which does occur in all organisms. The question of bioconcentration in an ocean environment was totally ignored in the statement.”

In its report to Forum member governments in August, the expert panel concluded that Japan’s assessments of ecological effects and bioconcentration are seriously deficient and don’t provide a sound basis for estimating impact. Writing in the Japan Times, the five scientists noted:

The release of contaminated material from the Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant would take at least forty years, and decades longer if you include the anticipated accumulation of new water during the process. This would impact not only the interests and reputation of the Japanese fishing community, among others, but also the people and countries of the entire Pacific region. This needs to be considered as a transboundary and transgenerational issue.

Insufficient information is available to assess how environmental and human health would be affected, they argued, and issuing a permit at this time would be premature at best: “Having studied the scientific and ecological aspects of the matter, we have concluded that the decision to release the contaminated water should be indefinitely postponed and other options for the tank water revisited until we have more complete data to evaluate the economic, environmental and human health costs of ocean release.”

The potential for long-term damage to the ocean environment is echoed by expert panel member Robert Richmond from the University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa.

“This is truly a trans-boundary issue,” he says. “Fish don’t respect political lines, and neither do radionuclides or pollutants in the ocean. I really commend the members of the Pacific Islands Forum for recognising this is an issue they need additional information on.”

Soon after the 2011 Fukushima accident, scientists confirmed that Pacific bluefin tuna can transport radionuclides across the northern Pacific Ocean. A 2012 study from Stanford University reported tuna with traces of Fukushima-related contamination had been found on the shores of the United States.

“Pacific bluefin tuna can rapidly transport radionuclides from a point source in Japan to distant ecoregions and demonstrate the importance of migratory animals as transport vectors of radionuclides,” the study reported. “Other large, highly migratory marine animals make extensive use of waters around Japan, and these animals may also be transport vectors of Fukushima-derived radionuclides to distant regions of the North and South Pacific Oceans.”

Will perceptions of radioactive hazards from Japan’s ocean dumping damage the global market for tuna? Many island nations derive vital revenue from the deepwater fishing nations that pay to operate in Pacific Island exclusive economic zones, or EEZs.

Regional organisations have also sought to process and market tuna from the Pacific as another key source of revenue. For nearly a decade, island states have supported Pacifical, a brand that promotes sustainable distribution and marketing of skipjack and yellowfin tuna caught in their EEZs.

Speaking after her recent appointment as executive director of the Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission, Rhea Moss-Christian highlighted the potential damage of Japan’s decades-long project: “This is a massive release and a big, big potential disaster if it’s not handled properly.”

Moss-Christian is the first Pacific woman to head the commission, which manages the largest tuna fishery in the world, representing nearly 60 per cent of global production.

“I wish that the Japanese government would take some more time before its release,” she told journalists at December’s commission meeting. “There are a number of outstanding questions that have yet to be fully answered. They have focused a lot on one particular radionuclide, and not very much on others that are also present in the wastewater.”

Moss-Christian is a citizen of the Republic of the Marshall Islands, an island nation living with the consequences of radioactive fallout from sixty-seven US atmospheric nuclear tests on Bikini and Enewetak Atolls. A former chair of the Marshall Islands National Nuclear Commission, she is deeply aware of this radioactive legacy. Her nation struggles to control radionuclides leaching into the marine environment from the Runit Dome, a nuclear waste site on Enewetak Atoll created by the United States in the 1970s.

“We have a lot of experience in the Marshall Islands with lingering radioactive waste,” Moss-Christian said. “We don’t want to find ourselves in another situation, not just in the Marshall Islands, but in general in the region, where we agree to something without knowing what could potentially happen in the future. What are the contingency plans? What are the compensation mechanisms?”

At a time of growing US–China tension, the Japanese government is seeking to boost its role in the islands region. Tokyo is building closer ties with Australia and the United States through increased military operations and joint investments in the islands. In November, for example, Tokyo and Washington agreed to contribute US$100 million to support Australian underwriting of Telstra’s purchase of Digicel, blocking Chinese investment in the Pacific’s key mobile phone network.

Even as the Japanese government seeks to win hearts and minds in the region, community anger about the nuclear threat is growing. Church and civil society groups, including the Pacific Conference of Churches, Pacific Islands Association of Non-Governmental Organisations and Pacific Network on Globalisation, have criticised the proposed wastewater dumping plan.

When Japanese foreign minister Yoshimasa Hayashi visited Fiji last May, these community groups argued the proposed ocean dumping breached international agreements like the London Convention on the Prevention of Marine Pollution. A joint civil society statement concluded, “We believe there is no scenario in which discharging nuclear waste into the Pacific Ocean is justified for the health, wellbeing, and future safety of Pacific peoples and the environment.”

As Japan forges ahead with its plan and Australia works towards acquiring nuclear submarines under the AUKUS agreement, the gulf is growing between the two countries’ geopolitical agenda and the growing antinuclear sentiment across the Blue Pacific. •

VOX POPULI: Shame on you, prime minister, for your blatant about-face

JR Namie Station, upper right, in Fukushima Prefecture is surrounded by vacant land in March 2019, after homes and shops damaged by the 2011 nuclear disaster were demolished.

December 24, 2022

Mariko Sato of the town of Namie, Fukushima Prefecture, said in March 2011: “Explosions at the nuclear power plant have forced me to evacuate twice already. What’s going to happen in the days ahead?”

“I’ve lived a bit too long. I saw something I didn’t want to see,” noted 102-year-old Fumio Okubo in April before he took his own life in front of his home in the village of Iitate.

One year later, 6-year-old Toya Matsuoka spoke of his dream: “I want to be rich when I grow up. I’m going to buy a big house that won’t be washed away by tsunami, so my entire family can live there.”

And Kunio Omori, 81, recalled his temporary return to his home in the town of Tomioka: “There were beautifully ripe, yellow fruits on apricot trees in my yard. But I couldn’t even pick them, let alone eat.”

Those are among comments by Fukushima residents who survived the Great East Japan Earthquake of March 2011 that triggered a nuclear disaster to tell their stories to The Asahi Shimbun.

Trying to remember what kind of future our nation sought back then, I re-read the clippings, placed side by side on my desk with stories that ran in yesterday’s paper.

And I was overcome with shocked disbelief: How could anyone completely forget something of such magnitude after only 11 years?

The Kishida administration on Dec. 23 announced a new policy to make “maximum use” of nuclear power.

The government will proceed with the hitherto “unanticipated” reconstruction of old facilities, will consider building new facilities and extend the life span of reactors to beyond 60 years.

The about-face is so total, I feel cheated.

And yet, the language of the new policy is shamelessly replete with lofty “assurances” such as, “Fukushima’s reconstruction is the basis on which (the nation’s) energy policy is to be pursued” and “the sobering lessons we learned from the accident will never be forgotten, not even for a second.”

A guilty heart is said to turn one’s ears red. And that is why the kanji for “haji” (shame) is made up of two radicals that stand for “ear” and “heart,” according to kanji scholar Shizuka Shirakawa (1910-2006), the author of “Joyo Jikai” (translated into English as The Keys to the Chinese Characters).

Prime Minister Fumio Kishida boasts about his “ability to listen.” I wonder if his new energy policy has made his ears turn red, even if for just a second.

If not, it’s just too sad.

Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant Accident: Two workers who developed leukemia and other illnesses while working on the plant premises are certified as workers’ compensation workers

December 23, 2022

The Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare (MHLW) has recognized a causal relationship between work and two men who developed leukemia and other illnesses while working inside the TEPCO’s Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant after the accident.

The two men, both in their 60s and 70s, worked for a TEPCO subcontractor and were involved in restoration work at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant after the accident in March 2011.

According to the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare, the man in his 60s was in charge of electrical system construction and was diagnosed in 2017 with “true red blood cell hyperplasia,” a cancer of the blood that increases the number of red blood cells.

Another man in his 70s was involved in the construction of new tanks and was diagnosed with leukemia last year.

Both men had been working at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant since before the accident, and their total exposure doses exceeded the guidelines for certification. The Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare recognized their work as having a causal relationship to their work.

Since the accident at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant, eight workers have been diagnosed with leukemia and thyroid cancer, bringing the total number of workers’ compensation cases to 10.

https://www3.nhk.or.jp/news/html/20221223/k10013933321000.html?fbclid=IwAR1IVXivzuHbmjsDsjDVZ8Ht5gj3nSLkNE_fJEQlTaiVU92 PqsIdnoZuDJA

JP Gov estimates Tepco to take 42 more years to compensate

Storage building of residuals from the contaminated water https://www.tepco.co.jp/decommission/visual/photo/index-j.html

The Board of Audit of Japan has estimated that it will take until fiscal year 2064 to recover the funds lent to TEPCO for compensation for the Fukushima nuclear accident. Four years ago, the Board of Audit estimated that the maximum period would be until fiscal 2051, but this time it has been extended by 13 years. There is still room for the amount of compensation TEPCO will pay to the victims and others to increase, and the Board has pointed out that “the timing of the completion of recovery may be extended even further in the future than this trial calculation.”

TEPCO has paid compensation for victims and the cost of decontamination work. In order to financially support this company, the government borrows funds from private financial institutions and issues government bonds to provide funds to TEPCO through the Nuclear Damage Compensation and Decommissioning Facilitation Corporation. The organization is proceeding with de facto repayment by paying “general contributions” from TEPCO and other electric power companies to the government.

According to the Board of Audit, 13.5 trillion yen (97B USD) in government bonds have been issued to support TEPCO so far, and about 8 trillion yen (58B USD) has not been returned to the government by the agency. In addition to the general contribution, the agency uses “special contribution from TEPCO” and “profit on sale of TEPCO shares by the agency” as the source of funds for the return.

Nevertheless, TEPCO’s financial situation and stock price have not improved as planned, and in the worst scenario by this moment, it would take another 42 years until 2064 to recover the full amount.

Next spring, it is planned that contaminated water from decommissioning work will begin to be discharged into the Pacific, which is anticipated to increase the amount of compensation. In addition, since the amount of compensation determined in lawsuits filed by victims and evacuees across the country already exceeds the expected line by the government guidelines, the amount of compensation is likely to increase even further if the guidelines are updated.

For this reason, the Board of Audit stated, “If Tepco ends up making more loans from the government due to the increasing compensation liability, the burden on the people will also increase.”

Court rejects calls to halt Kansai Electric’s aging nuclear reactor

Dec 20, 2022

Osaka – The Osaka District Court on Tuesday rejected local residents’ calls to halt an aging nuclear reactor at Kansai Electric Power’s Mihama power plant in central Japan that started operations more than 40 years ago.

The court ruling marked the first judicial decision over the safety of an aging reactor. It was handed down after local residents sought suspension of the No. 3 unit of the plant in Fukui Prefecture due to safety concerns.

The decision came as the government seeks to extend the maximum service period for the country’s existing nuclear reactors beyond 60 years. The reactor is the only one that operates in Japan beyond the country’s 40-year service period in principle.

Nine residents in Fukui, Shiga and Kyoto prefectures living within a 10- to 80-kilometer radius of the plant argued the reactor would not be able to withstand a massive earthquake due to the likelihood that facilities and equipment have deteriorated over time.

Such a situation poses a risk of exposure to radiation caused by the spread of radioactive materials, the residents said, adding that the current evacuation plan is not effective, as the route passes by other nuclear plants and destination sites are located where radioactive materials could reach.

However, the court ruled that there is no problem with Kansai Electric’s safety measures against earthquakes and that steps taken against the aging of the reactor are also reasonable.

Kansai Electric had argued the safety of the reactor is ensured as it complies with the new regulatory standards established on lessons learned from the 2011 nuclear disaster that was caused by a massive earthquake and tsunami.

In June 2021, the No. 3 unit became the first nuclear reactor to operate beyond 40 years under the new rules that limit a reactor’s service period to 40 years in principle, although it can be extended by up to 20 years if approved by the Nuclear Regulation Authority.

The unit was halted just four months after being restarted as it failed to implement anti-terrorism measures in time and also suffered a water leakage before being started up again on Aug. 30 this year. It resumed operations on Sept. 26.

Units No. 1 and 2 of the Mihama plant were terminated in April 2015 in line with the 40-year limit.

https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2022/12/20/national/crime-legal/mihama-ruling/

Scope of Fukushima nuclear accident compensation expanded

A gate leading to a “difficult-to-return zone” is closed by a government official in a town in Fukushima Prefecture in May 2013.

December 21, 2022

Psychological damage stemming from the March 2011 Fukushima nuclear power plant accident is being recognized by a government panel as eligible for compensation.

This policy was included in interim guidelines being compiled for the first time in nine years by the Dispute Reconciliation Committee for Nuclear Damage Compensation on Tuesday.

It will significantly expand the scope of compensation for people affected by changes to their livelihood due to a long period of evacuation from areas around the Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant.

The guidelines set the standards for compensation from Tokyo Electric Power Company Holdings Inc. following the nuclear accident at its plant.

As part of the revisions to the guidelines, rulings in lawsuits filed by evacuees will also be applied to non-plaintiffs.

The new guidelines recognize psychological damage caused by changes in living conditions of people who not only lived in the “difficult-to-return zones,” but also those who live in other evacuation-designated zones. This means additional compensation of up to ¥2.5 million each for about 30,000 people living in “restricted residence zones” and about 40,000 residents of “evacuation order cancellation preparation zones.”

For people who used to live within a 20-kilometer radius of the plant, an additional ¥300,000 is set to be paid on the grounds that they were forced to endure harsh evacuation conditions.

As for former residents of Fukushima City and other areas that are not included in evacuation zones but were subject to voluntary evacuation, the new guidelines raise the amount of compensation. An adult who is not pregnant will be eligible for ¥200,000, up from ¥80,000.

“We don’t think of these guidelines as caps on compensation,” TEPCO President Tomoaki Kobayakawa said to reporters at the of Economy, Trade and Industry Ministry. “We would like to respond sincerely to the matter.”

Kobayakawa indicated that TEPCO would continue to provide compensation to the southern part of Fukushima Prefecture, which is not included in the guidelines.

The latest revision is expected to cost TEPCO additional compensation of ¥500 billion.

Source: https://japannews.yomiuri.co.jp/society/general-news/20221221-78746/

Government panel revises guidelines for Fukushima compensation

Dec. 20, 2022

A government panel has revised a set of guidelines for the amount of compensation to be paid to people in Fukushima who have been affected by the accidents at Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant in 2011. This is the first revision of the guidelines in nine years.

The revised set of guidelines will make more people eligible for compensation.

People who have evacuated from some of the areas outside the government-designated no-go-zones will now be eligible for compensation worth 2.5 million yen per person.

Those who lived in “evacuation preparation zones” within a radius of 20 to 30 kilometers of the nuclear plant will be paid 500,000 yen in compensation.

The panel for the first time said that these sums will not be the ceiling.

It called on Tokyo Electric Power Company to be flexible in paying damages to those not included in the new guidelines.

NZ and Pacific urged to ‘step up’ against Japan’s nuclear plan

An estimated 30,000 anti-nuclear activists attended a rally in Tokyo’s Yoyogi Park, in 2012, to protest against the government’s plan to reopen several of Japan’s nuclear reactors.

Dec 17 2022

Japan’s decision to discharge nuclear wastewater into the Pacific Ocean for the next 30 years has been condemned by a Pacific alliance.

And the group of community members, academics, legal experts, NGOs and activists is calling on New Zealand and the Pacific to act to stop Japan.

Three reactors at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant had meltdowns after the earthquake and tsunami on March 11, 2011 which left more than 15,000 people dead.

The Japanese government said work to clean up the radioactive contamination would take up to 40 years.

Following the Nuclear Connections Across Oceania Conference at the University of Otago last month, a working group was formed to address the planned discharge.

Dr Karly Burch at the OU’s Centre for Sustainability said many people might be surprised to hear that the Japanese government has instructed Tokyo Electric Power Company (Tepco) to discharge more than 1.3 million tonnes of radioactive wastewater into the ocean from next year.

Burch said they had called on Tepco to halt its discharge plans, and the New Zealand Government to “step up against Japan”.

In June, Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern called for nuclear disarmament during her speech at the Nato Leaders’ Summit in Madrid.

Jacinda Ardern with Pacific Islands Forum secretary-general Henry Puna, left, and forum chair and Fijian PM Frank Bainimarama during the leaders’ summit in Fiji in July.

“New Zealand is a Pacific nation and our region bears the scars of decades of nuclear testing. It was because of these lessons that New Zealand has long declared itself proudly nuclear-free,” Ardern said.

Burch said the Government must “stay true to its dedication to a nuclear-free Pacific” by taking a case to the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea against Japan.

“This issue is complex and relates to nuclear safety rather than nuclear weapons or nuclear disarmament,” the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade said in a statement on Friday.

“Japan is talking to Pacific partners in light of their concerns about the release of treated water from Fukushima and Aotearoa New Zealand supports the continuation of this dialogue.

“There is also an important role for the global expert authority on nuclear safety issues, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), which Japan has invited to review and monitor its plans.

“Aotearoa New Zealand is following the reports released by the IAEA Task Force closely and has full confidence in its advice,” MFAT said.

In Onahama, 60km from the power station, fish stocks have dwindled, said Nozaki Tetsu, of the Fukushima Fisheries Co-operative Associations.

“From 25,000 tonnes per year before 2011, only 5000 tonnes of fish are now caught,” he said. “We are against the release of radioactive materials into our waters. What worries us is the negative reputation this creates.”

Storage tanks for radioactive water stand at Tokyo Electric Power Co.’s (Tepco) Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear power plant on January 29, 2020 in Okuma, Fukushima Prefecture, Japan.

Japan needs nuclear power because its energy grid is not connected to neighbouring countries nor is it able to boost output of domestic fossil fuels, a government official in Tokyo said in a statement.

Japan has kept most of its nuclear plants idled since the 2011 earthquake and tsunami. In September, the government announced it would restart the power plants to develop the country’s next-generation nuclear reactors.

Japan has been decommissioning and decontaminating the Fukushima nuclear power plant.

Now, it must urgently empty its water tanks.

Burch said predictive models showed radioactive particles released would spread to the northern Pacific.

Dr Karly Burch says the New Zealand Government must stay true to its dedication to a nuclear-free Pacific.

“To ensure they do not cause biological or ecological harm, these uranium-derived radionuclides need to be stored securely for the amount of time it takes for them to decay to a more stable state. For a radionuclide such as Iodine-129, this could be 160 million years.”

Burch said Tepco had been using advanced liquid processing system technology to filter uranium-derived radionuclides from the wastewater that had been cooling the damaged reactors since 2011.

Burch said the Japanese government was aware in August 2018 that the treated wastewater contained long-lasting radionuclides such as Iodine-129 in quantities exceeding government regulations.

She has called for clarity from Tokyo, the International Atomic Energy Agency, the Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat, Pacific Oceans Commission, and a Pacific panel of independent global experts on nuclear issues on the outcome of numerous meetings they have had about the discharge.

“We want a transparent and accountable consultation process which would include Japanese civil society groups, Pacific leaders and regional organisations.

“These processes must be directed by impacted communities within Japan and throughout the Pacific to facilitate fair and open public deliberations and rigorous scientific debate,” Burch said.

The Pacific Islands Forum secretary-general, Henry Puna, has been approached for comment.

Decontamination work to start in more parts of Fukushima in FY 2023

Dec. 16, 2022

The Japanese government says decontamination work will start next fiscal year in more parts of Fukushima Prefecture that remain off limits following the March 2011 nuclear accident.

Authorities designated the areas as “difficult-to-return zones”, and evacuation orders remain in effect.

On Friday, Reconstruction Minister Akiba Kenya said the decontamination work includes parts of Okuma and Futaba towns.

A detailed schedule remains undecided, but the work will begin in the fiscal year starting next April.

The government plans to fund the work with 6 billion yen, or nearly 44 million dollars, from the state budget.

Some parts of the “difficult-to-return zones” have already been cleaned up so that people can return.

The ruling coalition has been urging the government to decontaminate more areas.

Discharging treated water from Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant “Not just a problem for Japan” International forum online Opposition from around the world

Citizens, lawyers, and scientists from Japan, the U.S., and other countries exchange opinions about the release of contaminated water from TEPCO’s Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant after purification and treatment at sea at an online forum.

December 17, 2022

Citizens of Fukushima Prefecture and others have been discussing a plan to discharge contaminated water from TEPCO’s Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant into the ocean. Citizens’ Council” held an online international forum on December 17, inviting citizens, scientists, lawyers, and others from countries and regions around the world, including the United States, Australia, and China. The participants commented, “The oceans are connected. It is not just a problem for Japan.” A number of participants expressed opposition to ocean discharge.

One hundred and eighty-eight people participated in the forum. A video was shown by Bedi Rasoulay, a student from the Marshall Islands in the Pacific Ocean, which has been the site of nuclear tests by the United States, Europe, and other nations. In the video, Ms. Lasure touched on the health problems faced by residents who returned to the islands after being told that they were safe to live there, and she said, “The ocean is our life. The Pacific Ocean is neither a nuclear test site nor a place to dump nuclear waste. If we discharge it into the ocean, it will be irreversible. I am against it.

Dr. Arjun McJourney, director of the U.S. Institute for Energy and Environmental Research, analyzed the data released by TEPCO with experts in oceanography, ecology, nuclear physics, and other fields. He said that the amount of sampling and the types of radioactive materials being monitored are too small to make the water safe for discharge, and pointed out that “there is a lack of research on the impact on the ecosystem and that other viable alternatives have not been adequately considered because of the oceanic discharge. He stated, “All options should be considered, and methods to minimize risk should be scientifically verified.”

Environmental groups from China, South Korea, Taiwan, Australia, and other countries sent messages saying that if the waste is discharged into the ocean, pollution will spread and affect not only neighboring countries in the Asia-Pacific region but also other countries in the region, and reported on the opposition movements in their respective regions.

Mr. Forss, an anti-nuclear activist from California, USA, suggested that “we should take action around the world at the same time in order to raise awareness of the issue.

Ruiko Muto, a member of the organizing group and a resident of Miharu-cho, Fukushima Prefecture, said, “We now know that the ocean discharge is a major international problem because it is an environmental pollution of the earth. We want to work together to prevent further environmental pollution by radiation from getting worse. (Natsuko Katayama)

https://www.tokyo-np.co.jp/article/220606?fbclid=IwAR3OcWXBYNTFX0R3Zu23sNPq

Pacific Alliance condemns radioactive discharge from Fukushima Daiichi – calls for NZ action

Panel organiser Dr Karly Burch and panellists discussing TEPCO’s wastewater discharge plan at the Nuclear Connections Across Oceania Conference 2022.

15 December 2022

Plans to discharge tonnes of radioactive wastewater into the Pacific Ocean for around thirty years have been condemned in a statement issued today by a Pacific-wide alliance.

Dr Karly Burch, of Otago’s Centre for Sustainability, says many people will be surprised to hear that the Japanese government has approved Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO) to discharge more than 1.3 million tonnes of radioactive wastewater, starting next year and for approximately 30 years.

Following the Nuclear Connections Across Oceania Conference, held at the University of Otago late last month, a working group was formed to address the planned radioactive wastewater discharge from TEPCO’s Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant impacted by the 2011 tsunami.

“We learned at our conference that people in Japan and throughout the Pacific are deeply concerned about the radioactive wastewater discharge,” says Dr Burch.

The emerging collective of community members, academics, legal experts, NGOs and activists from Japan and across the Pacific, who met through the conference, have co‑authored a statement of solidarity calling on TEPCO to halt their discharge plans and for the New Zealand Government to “stay true to its commitment to a nuclear free Pacific” by taking a case to the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea against Japan’s nuclear waste disposal plans.

Greenpeace Aotearoa Senior Campaigner Steve Abel says: “It’s right that the New Zealand government should stand in solidarity with Pacific neighbours and through international legal action directly oppose the discharge of nuclear waste into the Pacific Ocean.”

Dr Burch says predictive models show that radioactive particles released will spread to the northern Pacific, so secure on-land storage should be used instead.

Most of the radionuclides that will be released in the wastewater discharge have been produced through the nuclear fission of uranium.

“To ensure they do not cause biological or ecological harm, these uranium-derived radionuclides need to be stored securely for the amount of time it takes for them to decay to a more stable state – for a radionuclide such as Iodine-129, this could be 160 million years,” says Dr Burch.

TEPCO is using Advanced Liquid Processing System (ALPS) technology to filter uranium-derived radionuclides from the wastewater that has been cooling damaged reactors at Fukushima Daiichi since the onset of the 2011 nuclear disaster.

“While in Japanese the radioactive wastewater is often referred to as ‘treated water’, this does not automatically mean that the water is free from uranium-derived radionuclides. It simply means the amount of measurable radionuclides are under a designated threshold limit.

“One thing the statement highlights is that the Japanese government has known since at least August 2018 that ALPS-treated wastewater contains long-lasting radionuclides such as Iodine-129 in quantities exceeding government regulations,” Dr Burch shared.

The statement of solidarity calls for the following resolutions:

- We call on TEPCO and the Japanese Government to immediately end its plan to discharge radioactive wastewater from Fukushima Daiichi into the Pacific Ocean.

- We call on the New Zealand government to stay true to its commitment to a nuclear free Pacific, and to support other concerned Pacific governments by playing a leading role in taking a case to the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea against Japan concerning the proposed radioactive release from TEPCO’s Fukushima Daiichi.

- We seek clarity from the Japanese Government, the International Atomic Energy Agency, Henry Puna (the Secretary General of the Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat and Pacific Ocean Commissioner), and the Pacific Panel of Independent Global Experts on Nuclear Issues on the outcome of numerous meetings they had about the radioactive wastewater discharge.

- We call for a transparent and accountable consultation process as called for by Japanese civil society groups, Pacific leaders, and regional organisations. This consultation would be between the Japanese government and its neighbours throughout the Pacific. These processes must be directed by impacted communities within Japan and throughout the Pacific to facilitate fair and open public deliberations and rigorous scientific debate.

“We invite anyone interested in this topic to read and sign our statement of solidarity,” says Dr Burch.

The full statement can be found on the Nuclear Connections Across Oceania website:

Our contaminated future

A rice field in Iitate, Fukushima prefecture, Japan, 2016.

is an assistant professor in the department of anthropology at Université Laval, in Quebec City, Canada. He is working on a book about the 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster, ‘Radioactive Governance: The Politics of Revitalization after Fukushima’.

As a farmer, Atsuo Tanizaki did not care much for the state’s maps of radioactive contamination. Colour-coded zoning restrictions might make sense for government workers, he told me, but ‘real’ people did not experience their environment through shades of red, orange and green. Instead, they navigated the landscape one field, one tree, one measurement at a time. ‘Case by case,’ he said, grimly, as he guided me along the narrow paths that separated his rice fields, on the outskirts of a small village in Japan’s Fukushima prefecture.

The author examines maps of radioactive contamination in Fukushima.

It was spring in 2016 when I first visited Tanizaki’s farm. The air was warm. The nearby mountains were thick with emerald forests of Japanese cedar, konara oak and hinoki cypress. A troop of wild red-faced monkeys stopped foraging to watch us as we walked by. And woven through it all – air, water, land, plants, and living bodies – were unseen radioactive pollutants. Almost everything now carried invisible traces of the 2011 meltdown at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant.

Tanizaki began taking measurements. With his Geiger counter, he showed me how radioactive elements were indifferent to the cartographic logic of the state. In some places, the radiation level dropped low, becoming almost insignificant. But here and there, beside a ditch or near a pond, the level was elevated dangerously high. Tanizaki called these areas ‘hot spots’ and they were scattered across the landscape, even within supposedly ‘safe’ zones on government maps. Contamination in Fukushima, he believed, was structured in a way that no state was prepared to solve.

A decade after the 2011 meltdown, the region remains contaminated by industrial pollution. Though attempts at removing pollutants continue, a new realisation has taken hold among many of Fukushima’s farmers: there’s no going back to an uncontaminated way of life.

Watching Tanizaki measuring industrial pollution in a toxic landscape neglected by the state, I began to wonder: is this a future that awaits us all?

As an anthropologist interested in contamination, Fukushima throws into sharp relief the question of what it means to live in a permanently polluted world. That is why I began coming to Japan, and spending time with farmers such as Tanizaki. I wanted to understand the social dynamics of this new world: to understand how radioactivity is governed after a nuclear disaster, and how different groups clash and collaborate as they attempt to navigate the road to recovery.

I expected to find social bonds pushed to breaking point. Stories of post-disaster collapse circulate in our collective consciousness – tales of mistrust, fear and isolation, accompanied by images of abandoned homes and towns reclaimed by plants and wildlife. And I found plenty of that. A sense of unravelling has indeed taken hold in rural Fukushima. Residents remain uncertain about the adverse health effects of living in the region. Village life has been transformed by forced evacuations and ongoing relocations. And state-sponsored attempts at revitalisation have been ineffective, or complete failures. Many communities remain fragmented. Some villages are still abandoned.

Farmers took matters into their own hands, embracing novel practices for living with toxic pollution

In Fukushima, I found a society collapsing under the weight of industrial pollution. But that’s only part of the story. I also found toxic solidarity.

Rather than giving up, Tanizaki and other farmers have taken matters into their own hands, embracing novel practices for living alongside toxic pollution. These practices go far beyond traditional ‘farming’. They involve weaving relationships with scientists, starting independent decontamination experiments, piloting projects to create food security, and developing new ways to monitor a changing environment. Among rice fields, orchards and flower beds, novel modes of social organisation are emerging – new ways of living from a future we will one day all reckon with.

But the story of toxic solidarity in Fukushima doesn’t begin among rice fields and farms. It begins under the Pacific Ocean, at 2:46pm on 11 March 2011. At that moment, a magnitude 9.0-9.1 earthquake off the coast of northeastern Japan caused a devastating tsunami that set in motion a chain of events leading to the meltdown of three reactors at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant. Soon, Fukushima would find its place alongside Three Mile Island and Chernobyl as an icon of nuclear disaster – and an emblem of the Anthropocene, the period when human activity has become the dominant influence on environmental change. As the reactors began to meltdown, pressure mounted in the power station’s facilities, leading to explosions that released dangerous radionuclides into the air, including caesium-134, caesium-137, strontium-90 and iodine-131. These isotopes, with lifespans ranging from days to centuries, blew across Fukushima and northeastern Japan. And as they accumulated, health risks increased – risks of cancers and ailments affecting the immune system. To protect the population, the Japanese state forced tens of thousands of citizens living near the reactors to evacuate.

Furekonbaggu, bags of contaminated soil, piled neatly in the Fukushima countryside.

At first, Tanizaki believed he had escaped the worst of the radiation because his village was not in the mandatory evacuation area. But when the wind carried radionuclides – invisible, tasteless, odourless – far beyond the government models, his village became one of the most contaminated areas in Fukushima. He learned he had been exposed to harmful radiation only when the government forced him to leave.

Tanizaki and other evacuated villagers were relocated to ‘temporary’ housing. As the months became years, Tanizaki longed to return to his life as a farmer. But what would he farm? His land had been irradiated, and no one wanted to eat food grown in radioactive topsoil. To help Fukushima’s rural citizens retrieve their farms, the Japanese government launched an official politics of revitalisation in Fukushima, investing trillions of yen to clean and decontaminate the region before repatriating evacuees. Part of the cleanup involved storing tainted topsoil in large black plastic bags known as furekonbaggu (literally ‘flexible container bags’), which were then stacked in piles throughout the countryside. To keep residents safe, the government also promised to track contamination through a monitoring system. At the time, the possibility of a pristine Fukushima seemed within reach.

In June 2015, after four years of forced evacuation, Tanizaki was finally allowed to return to his farm. But the decontamination efforts had failed. He and many others felt they had been returned to a region abandoned by the government. The landscape was now covered in millions of bags of radioactive topsoil – black pyramids of the Anthropocene – while the government waited for a permanent disposal site. Also, the plastic in some furekonbaggu had already broken down, spilling radioactive soil over freshly decontaminated land. The state’s monitoring efforts were equally inadequate. In Tanizaki’s village, the monitoring of airborne radiation produced measurements that were rarely precise enough to give a complete picture of shifting contamination. Villagers lived with constant uncertainty: is the garden contaminated? Are the trees behind the house safe? Are mushrooms in the forest still edible?

I saw dead sunflowers rooted in irradiated fields – withered emblems of dreams to retrieve Fukushima

For some, the uncertainty was too much. Tens of thousands relocated to other parts of Japan rather than returning. In 2010, the region registered 82,000 people whose main income came from farming. But by 2020, that number had fallen to around 50,000. Abandoned greenhouses and fields can still be found dotted across the landscape.

Withered sunflowers in irradiated fields.

Knowing that government efforts weren’t going to help, some returnees began to decontaminate their own villages and farms. There was hope that the region could be returned to its former uncontaminated glory. One proposed method involved planting sunflowers, which were believed to absorb radiation as they grew. Yellow flowers bloomed across the farmlands of Fukushima. However, the results were unsatisfactory. Even during my time in Japan, years after the disaster, I saw dead sunflowers still rooted in irradiated fields – withered emblems of early dreams to retrieve a pre-disaster Fukushima. I also witnessed decontamination experiments in rice paddies: farmers would flood their fields, and then use tools to mix the water with the irradiated topsoil below, stirring up and dislodging radioactive pollutants such as caesium. The muddy water was then pushed out of the field using large stiff-bristled brushes. This project also failed. Some paddy fields are still so contaminated they can’t grow rice that’s safe for human consumption.

These failures significantly affected the morale of Fukushima’s farmers, especially considering the importance of the region as a rice-growing capital. Once easy decontamination efforts failed, returnees were forced to ask themselves difficult questions about their homes, livelihoods and identities: what will happen if farming is impossible? What does it mean to be a rice farmer when you can’t grow rice? What if life has been irrevocably altered?

Even the mushrooms tasted different. One farmer, Takeshi Mito, told me he had learned to grow shiitake mushrooms on artificial tree trunks, since real trees were too contaminated to produce edible fungi. ‘Now the taste of the shiitake has changed,’ he mumbled, a strange sadness filling his voice. The ‘real’ trees had given the mushrooms a special flavour, just like ageing a whisky in a sherry cask. ‘Yeah,’ he said, pausing to remember. ‘They were good.’

A new reality was emerging. Farmers were learning to accept that life in Fukushima would never be the same. Small details are constant reminders of that transformation, like the taste of mushrooms, or the library in Tanizaki’s home, which is now filled with books on Chernobyl, nuclear power, radioactive contamination, and food safety. This is new terrain, in which everyone carries a monitoring device, and in which everyone must learn to live with contamination. A former way of life may be impossible to retrieve, and attempts at decontamination may have failed, but farmers such as Tanizaki are learning to form new relationships to their irradiated environment. They’re forging new communities, reshaping notions of recovery, and reimagining their shared identities and values. Contamination may appear to have divided Fukushima’s farmers, but it has also united them in strange and unexpected ways.

By the time the evacuees were allowed to return to their homes, government mistrust had become widespread. Official promises were made to Fukushima residents that a nuclear disaster was impossible. These promises were spectacularly broken when radiation spread across the region. A lack of information from state sources made things only worse, leading to a growing sense that the government was unable to provide any real solutions. Not trusting state scientists, but still wanting to know more about the invisible harm in their villages, farmers reached out to academics, nongovernmental organisations and independent scientists in the hope of better understanding radioactivity.

These new relationships quickly changed social life in rural communities, and brought an influx of radiation monitoring devices. Rather than asking for additional state resources (or waiting endlessly for official responses to questions), farmers worked with their new networks to track radiation, measuring roads, houses, crop fields, forest areas and wildlife. Everyone learned to use radiation monitoring devices, which quickly became essential bodily extensions to navigate a changed Fukushima. Many rural communities even began to use them to develop their own maps. I remember the walls of Tanizaki’s home being covered in printed images showing the topography of the local landscape, with up-to-date information about radiation often provided by farmers. Local knowledge of the environment, combined with the technical savoir faire of independent scientists, produced far more accurate representations of contamination than the state maps made by government experts.

Sharing the work of living with contamination provided a feeling of communal life that returnees had so missed