This week in nuclear news

A vertical garden at Medellin’s City Hall.

Ralph Nader: Stop the Worsening Undercount of Palestinian Casualties in Gaza.

The horrors of nuclear weapons testing.

March 11 – reflecting on Fukushima.

********************************************

Climate. Climate change is warping the seasons. The world is not moving fast enough on climate change — social sciences can help explain why.Europe unprepared for rapidly growing climate risks, report finds.

Noel’s notes. The need for clear thinking on the Holocaust in Gaza. Oh for a bit of sanity and genuine leadership! Normalising the unthinkable – the 16th Annual Nuclear (so-called) Deterrence Summit.

NUCLEAR ISSUES

| EMPLOYMENT. Fukushima fishers strive to recover catches amid water concerns. | ENVIRONMENT. Hinkley Point Responds to Environmental Concerns Over Bristol Channel Eel Populations. | ETHICS and RELIGION. Aiding Those We Kill: US Humanitarianism in Gaza. The West has set itself on a path of collective suicide — both moral and economic’ Oceans. Could Fukushima’s radioactive water pose lasting threat to humans and the environment? |

| HISTORY. The lesson from the criminal H Bomb Bravo “test”– Hibakusha remind us. Oppenheimer feared nuclear annihilation – and only a chance pause by a Soviet submariner kept it from happening in 1962 | MEDIA. New York Times: Nuclear Risks Have Not Gone Away.US Media and Factcheckers Fail to Note Israel’s Refutation of ‘Beheaded Babies’ Stories. ‘Mr Dutton is right’: Murdoch’s News Corp papers grant nuclear power glowing coverage. NewsGuard AI Censorship Targets People Who Read Primary Sources To Fact-Check The News. – (a pro-Trumpist article?- but probably true) | OPPOSITION to NUCLEAR . ‘It’ll be a shortlist of one!’ Villagers in England fear nuclear dump proposal. An Open Letter from Hollywood On Oppenheimer and Nuclear Weapons. Kenya. Senator Omtatah to take the Uyombo nuclear power plant war international. |

| POLITICS Australia’s Opposition party’s nuclear red herring is a betrayal of the Australian people . – also at https://antinuclear.net/2024/03/11/1-a-coalitions-nuclear-red-herring-is-a-betrayal-of-the-australian-people/ . Australia has had many significant inquiries into nuclear power, over the past 60 years. Scottish National Party ministers to set out plans for removing nuclear weapons after independence. UK Labour versus Green. UK Budget: Government confirms £160m deal to acquire Hitachi nuclear sites. U.S. Congress about to fund revival of nuclear waste recycling to be led by private start-ups. | SAFETY. Greenpeace warns on danger of restarting Zaporizhzhia nuclear plant . Improvement notice served over storage of hazardous materials at Dounreay. ‘Sometimes I can’t sleep at night’: Adi Roche warns of nuclear risks of Ukraine conflict as she picks up peace award. Aberdeen shipping logistics company warned over nuclear transport safety failings.. | SPACE. EXPLORATION, WEAPONS. China outlines position on use of space resources. Russia says it is considering putting a nuclear power plant on the moon with China. Russia and China announce plan to build shared nuclear reactor on the moon by 2035, ‘without humans’. |

WEAPONS and WEAPONS SALES.

- The West’s over-involvement in Ukraine.

- F-35A aeroplanes officially certified to carry thermonuclear bomb. NATO bringing missiles closer to Russia – member state.

- Plutonium. Plutonium pit ‘panic’ threatens America’s nuclear ambitions. Does the US Need New Plutonium Pits?.

- Biden is building for Israel a super weapon to replace the Iron Dome.

- Coalition Kill Chain for the Pacific: Lessons from Ukraine. U.S. Sells ‘Link 16’ Battlefield Communications System to Taiwan – https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SfF4In5Q99Q

- AUKUS: Are nuclear-powered submarines a good idea for Australia?

WOMEN. Our International Women’s Day Heroine: Rosalie Bertell.

Fukushima, the Hidden Side of the Story

“The Fukushima Disaster, The Hidden Side of the Story,” is a just-released film documentary, a powerful, moving, information-full film that is superbly made. Directed and edited by Philippe Carillo, it is among the strongest ever made on the deadly dangers of nuclear technology.

It begins with the words in 1961 of U.S. President John F. Kennedy: “Every man, woman and child lives under a nuclear sword of Damocles, hanging by the slenderest of threads, capable of being cut at any moment by an accident, or miscalculation or by madness.”

It then goes to the March 2011 disaster at the Fukushima Daichi nuclear power plants in Japan after they were struck by a tsunami. Their back-up diesel generators were kicked in but “did not run for long,” notes the documentary. That led to three of the six plants exploding—and there’s video of this—“releasing an unpreceded amount of nuclear radiation into the air.”

“Fukushima is the world’s largest ever industrial catastrophe,” says Professor John Keane of the University of Sydney in Australia. He says there was no emergency plan and, as to the owner of Fukushima, Tokyo Electric Power Company, with the accident its CEO “for five nights and days…locked himself inside his office.”

Meanwhile, from TEPCO, there was “only good news” with two Japanese government agencies also “involved in the cover-up”—the Nuclear Industry Safety Agency and Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry.

“Japanese media was ordered to censor information. The Japanese government failed to protect its people,” the documentary relates.

Yumi Kikuchi of Fukushima, since a leader of the Fukushima Kids Project, recalls: “On TV, they said that ‘it’s under control’ and they kept saying that for two months. The nuclear power plant had already melted and even exploded but they never admitted the meltdown until May. So, people in Fukushima during that time were severely exposed to radiation.”

Arnie Gundersen, a nuclear engineer and now a principal of Fairewinds Energy Education in Burlington, Vermont, speaks of being told by Naoto Kan, the prime minister of Japan at the time of the accident, that “our existence as a sovereign nation was at stake because of the disaster at Fukushima Daichi.”

Kan then appears in documentary and speaks of “manmade” links to the disaster.

The documentary tells how Kan, following the accident, became “an advocate against nuclear power….ordered all nuclear power plants in Japan to shut down for safety” and for the nation “to move into renewable energy.”

But, subsequently, “a nuclear advocate,” Shinzo Abe, became Japan’s prime minister.

Yoichi Shimatsu, a former Japan Times journalist, appears in the film and speaks of “the cruelty, the cynicism of this government.” He speaks of how in the accident’s aftermath, “nearly every member of Parliament and leaders of the major political parties” along with corporate executives, “moved their relatives out of Japan”

He says “Shanghai is the largest Japanese community outside Japan now…while these same people” had been “telling the people of Fukushima go home, 10 kilometers from Fukushima, go home it’s safe, while their families are overseas in Los Angeles, in Paris, in London and in Shanghai.”

“If it’s safe, why they left?” asks Kikuchi. “They tell us it’s safe to live in Fukushima, and to eat Fukushima food to support Fukushima people. There’s a campaign by Japanese government…and people believe it.”

Gundersen says: “At Fukushima Daichi, the world is already seeing deaths from cancer related to the disaster…There’ll be many more over time.” He adds that there’s been a “huge increase in thyroid cancer in the surrounding population.”

“Unfortunately,” he goes on, “the Japanese government is not telling us al the evidence. There’s a lot of pressure on the scientists and the medical community to distort the evidence so there’s no blowback against nuclear power.”

There is a section in the documentary on the impacts of radioactivity which includes Dr. Helen Caldicott, former president of Physician for Social Responsibility, discussing the impacts of radiation on the body and how it causes cancer. She states: “There is no safe level of radiation. I repeat, there is no safe level of radiation. Each dose of radiation is cumulative and adds to your risk of getting cancer and that’s absolutely documented in the medical literature.”

“The nuclear industry says, well,” Dr. Caldicott, continues, “there are ‘safe doses’ of radiation and even says a little bit of radiation is good for you and that is called the theory of hormesis. They lie and they lie and they lie.”

Maggie Gundersen, who was a reporter and then a public relations representative for the nuclear industry and, like her husband Arnie became an opponent of nuclear power, speaks of how nuclear power derives from the World War II Manhattan Project program to develop atomic weapons and post-war so-called “Atoms for Peace” push.

Gundersen says in becoming a nuclear industry spokesperson, “the things I was taught weren’t true.” The notion, for example, that what is called a containment at a nuclear plant is untrue because radioactivity “escapes every day as a nuclear power plant operates” and in a “calamity” is released massively.

As to economics, she cited the claim decades ago that nuclear power would be “too cheap to meter.” The president of Fairewinds Energy Education, she says: “Atomic power is now the most expensive power there is on the planet. It is not feasible. It never has been.” Regarding the radioactive waste produced by nuclear power, she says “there is literally no technology to do that…It does not exist.”

As to international oversight, the documentary presents the final version of a “Report of the United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation” issued in 2014 which finds that the radiation doses from Fukushima “to the general public during the first year and estimated for their lifetimes are generally low or very low….The most important effect is on mental and social well-being.”

Shimatsu says it is not only in Japan but on an international level that the consequences of radioactive exposure have been completely minimized or denied. “We are all seeing a global political agreement centered in the UN organizations, tie IAEA [International Atomic Energy Agency], the World Health Organization…All the international agencies are whitewashing what is happening in Fukushima. We take dosimeters and Geiger counters in there, we see a much different story,” he says.

In Germany, says Maggie Gunderson, “the politicians chose” to do a study to “substantiate” that no health impacts “happened around nuclear power plants….But what they found was the radiation releases cause significant numbers of childhood leukemia.” A summary of that 2008 study comes on the screen. The U.S. followed up on that research, she says, but recently “the [U.S.] Nuclear Regulatory Commission said it was not going to do that study,” that “it doesn’t have enough funding; it had to shut it down.” She said the real reason was that it was producing “data they don’t want to make public.”

Beyond the airborne releases of radiation after the Fukushima accident, now, says the documentary, there is the growing threat of radioactivity through water that has and still is leaking from the plants as well as more than a million tons of radioactive water stored in a thousand tanks built at the plant site. After the accident, TEPCO released 300,000 tons of radioactive water into the Pacific Ocean. Now there is no land for more tanks, so the Japanese government, the documentary relates, has decided that starting this year to dump massive amounts of radioactive water over a 30-year period into the Pacific.

Arnie Gundersen speaks of the cliché that “the solution to pollution is dilution,” but with the radiation from Fukushima being sent into the Pacific, there will be “bio-accumulation”—with vegetation absorbing radiation, little fish eating that vegetation and intensifying it and bigger fish eating the smaller fish and further bio-accumulating the radioactivity. Already, tuna off California have been found with radiation traced to Fukushima. With this planned further, and yet greater dispersal, thousands of people “in the Pacific basin will die from radiation,” he says.

Andrew Napuat, a member of the Parliament of the nation of Vanuatu, an 83 island archipelago in the Pacific, says in the documentary: “We have the right to say no to the Japan solution. We can’t let them jeopardize our sustenance and livelihood.” Vanuatu along with 13 other countries has signed and ratified the South Pacific Nuclear Free Zone Treaty.

As the documentary nears its end, Arnie Gundersen says that considering the meltdown at the Three Mile Island nuclear plant in Pennsylvania in 1979, the meltdown at the Chernobyl nuclear plant in Ukraine in 1986, and now the three Fukushima meltdowns in 2011, there has been “a meltdown every seven years roughly.” He says: “Essentially, once every decade the world needs to know that there might be an atomic meltdown somewhere.” And, he adds, the “nuclear industry is saying they want would like to build as many as 5,000 new nuclear power plants.” (There are 440 in the world today.)

Meanwhile, he says, “renewable power is no longer alternative power. It’s on our doorstep. It’s here now and it works and it’s cheaper than nuclear.” The cost of producing energy from wind, he says, is three cents a kilowatt hour, for solar five cents, and for new nuclear power plants 15 cents. Nuclear “makes no nuclear economic sense.”

Maggie Gundersen says, with tears in her eyes: “I’m a woman and I feel it’s inherent for us as women to protect our children our grandchildren, and it’s our job now to raise our voices and have this madness stop.”

Philippe Carillo, from France, who worked for 14 years in Hollywood and who since 2017 has lived in Vanuatu, has worked on several major TV documentary projects for the BBC, 20th Century Fox and French National TV as well as doing independent productions. He says he made “The Fukushima Disaster, The Hidden Side of the Story” to “expose the nuclear industry and its lies.” His previous award-winning documentary, “Inside the Garbage of the World,” has made changes regarding the use of plastic.

“The Fukushima Disaster, The Hidden Side of the Story” can be viewed at Amazon, Apple TV, iTunes, Google Play and Vimeo on demand. Links are: iTunes: https://itunes.apple.com/us/movie/the-fukushima-disaster/id1672643918?ls=1 Apple TV: https://tv.apple.com/us/movie/the-fukushima-disaster/umc.cmc.3rfome5kj2hfpo2q9fwx5u0y0 Amazon UK: www.amazon.co.uk/placeholder_title/dp/B0B8TLPZ9K/ref=sr_1_1Amazon USA: https://www.amazon.com/Fukushima-Disaster-Yoichi-Shimatsu/dp/B0B8TLSRN4/ref=sr_1_1 Google Play: https://play.google.com/store/movies/details?id=vehqb5ex-L8.P&sticky_source_country=US&gl=US&hl=en&pli=1 Video on demand: https://vimeo.com/ondemand/thefukushimadisaster

Also, extra footage and interviews not in the film are at www.exposurefilmstrust.com

Karl Grossman, professor of journalism at State University of New York/College at Old Westbury, and is the author of the book, The Wrong Stuff: The Space’s Program’s Nuclear Threat to Our Planet, and the Beyond Nuclear handbook, The U.S. Space Force and the dangers of nuclear power and nuclear war in space. Grossman is an associate of the media watch group Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting (FAIR). He is a contributor to Hopeless: Barack Obama and the Politics of Illusion.

Stopping covering the Fukushima nuclear disaster

April 11, 2023

The Fukushima Nuclear disaster will continue to affect the people on location and others, as well as our environment for many more years, I will not continue.

I have been following the Fukushima nuclear accident for the past 12 years, spending a lot of time in sharing those news, to the somehow detriment of my own personal life.

Unlike some other people I entered this activity without seeking to make money or gain fame, I am just a simple citizen living on my basic minimum retirement pension. I shared Fukushima news weekly for the past 12 years but on the other hand I was unable to go visit my daughter in Iwaki, Fukushima since June 2011, because my financial situation is very tight, and Japan is way too expensive, overpriced for my meager wallet.

That situation has been tearing apart, on one hand to share Fukushima news and on the other hand to be unable to visit my own daughter in Fukushima.

I cannot take it anymore, so I decided to end this situation, to stop sharing the Fukushima news, to stop my lttle Fukushima blog, to disengage myself from it all, and to finally concentrate only on my little personal life.

That attitude of the Japanese government is nothing new. They have always lack a sense of responsibility, hiding behind hypocritical denials and false excuses, lies and covering-up.

The Japanese government has always faced accusations with duplicity when it comes to various events and issues that have marred their history. Some of these issues include the Nanjing massacre, Korean and Filipina sex slaves during World War II, the Minamata tragedy affecting thousands of lives, whale and dolphin fishing, the Fukushima nuclear disaster, and the dumping of radioactive water into the Pacific Ocean.

One of the most controversial events in Japan’s history is the Nanjing massacre, which occurred in 1937 when Japanese forces invaded the Chinese city of Nanjing. During the six-week occupation, Japanese soldiers carried out a brutal campaign of murder, rape, and looting, resulting in the deaths of an estimated 300,000 Chinese civilians and prisoners of war. Despite overwhelming evidence of the massacre, the Japanese government has been accused of downplaying its significance and even denying that it occurred.

Another issue that has caused controversy is the use of Korean and Filipina women as sex slaves during World War II. These women, known as “comfort women,” were forced into sexual servitude by the Japanese military, with an estimated 200,000 women being subjected to this treatment. Despite numerous apologies and compensation payments made to some of the victims, the Japanese government has been accused of failing to fully acknowledge and take responsibility for this atrocity.

Minamata disease is a neurological disease caused by severe mercury poisoning. Signs and symptoms include ataxia, numbness in the hands and feet, general muscle weakness, loss of peripheral vision, and damage to hearing and speech. In extreme cases, insanity, paralysis, coma, and death follow within weeks of the onset of symptoms. A congenital form of the disease affects fetuses in the womb, causing microcephaly, extensive cerebral damage, and symptoms similar to those seen in cerebral palsy.

Minamata disease was first discovered in the city of Minamata, Kumamoto Prefecture, Japan, in 1956, hence its name. It was caused by the release of methylmercury in the industrial wastewater from a chemical factory owned by the Chisso Corporation, which continued from 1932 to 1968. It has also been suggested that some of the mercury sulfate in the wastewater was also metabolized to methylmercury by bacteria in the sediment. This highly toxic chemical bioaccumulated and biomagnified in shellfish and fish in Minamata Bay and the Shiranui Sea, which, when eaten by the local population, resulted in mercury poisoning. The poisoning and resulting deaths of both humans and animals continued for 36 years, while Chisso and the Kumamoto prefectural government did little to prevent the epidemic.

As of March 2001, 2,265 victims had been officially recognized as having Minamata disease and over 10,000 had received financial compensation from Chisso. By 2004, Chisso had paid $86 million in compensation, and in the same year was ordered to clean up its contamination. On March 29, 2010, a settlement was reached to compensate as-yet uncertified victims.

In addition to these human rights abuses, Japan has also faced criticism for its continued practice of whale and dolphin fishing. Despite a global ban on commercial whaling, Japan continues to hunt whales under the guise of “scientific research,” and dolphins are also hunted and captured for use in entertainment parks. Many animal rights activists and conservationists have called for an end to these practices, but the Japanese government has been accused of prioritizing economic interests over environmental concerns.

Another event that has caused significant controversy is the Fukushima nuclear disaster, which occurred in 2011 after a massive earthquake and tsunami struck Japan. The disaster resulted in a meltdown at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant and the release of radioactive materials into the environment. While the Japanese government initially downplayed the severity of the disaster, it has since been accused of covering up information and failing to adequately respond to the crisis.

Perhaps one of the most recent controversies surrounding Japan involves the planned dumping of radioactive water from the Fukushima plant into the Pacific Ocean. Despite widespread opposition from environmental groups and neighboring countries, the Japanese government has defended the plan, claiming that the water will be treated and diluted before being released. However, many remain skeptical of these claims and fear the potential consequences of this decision.

In conclusion, the Japanese government has been accused of duplicity when it comes to a variety of issues that have marred their history and present-day actions. From human rights abuses to environmental disasters, the Japanese government has been criticized for downplaying or denying the severity of these events and failing to take responsibility for their actions. As such, it is imperative that the government is held accountable for its actions and takes concrete steps towards acknowledging and rectifying these issues.

The Japanese government as learned nothing from this nuclear tragedy, which they have conveniently sweeped under the carpet. Economics in their eyes always more important than people’s lives, PM Kishida promoting as of today the rebirth of nuclear full blast, wheras the consequences of the Fukushima nuclear disater have neither been yet adressed nor solved.

Best wishes to you,

Hervé Courtois

NH 608: Fukushima Child Thyroid Cancer Rates Soar – Joseph Mangano

February 14, 2023

Last year, a report revealed that Fukushima child thyroid cancer rates had skyrocketed – but still, the government of Japan and the nuclear industry refuse to take these statistics seriously.

But in truth – how bad is it? We interviewed a genuine expert to find out.

Joseph Mangano is Executive Director of Radiation and Public Health Project. He is an epidemiologist – one who searches for the cause of disease, identifies people who are at risk, determines how to control or stop the spread, or prevent it from happening again. Joe has over 30 years of experience working with nuclear numbers and comes from a history of teasing out health information from data. We spoke on Friday, February 11, 2022.

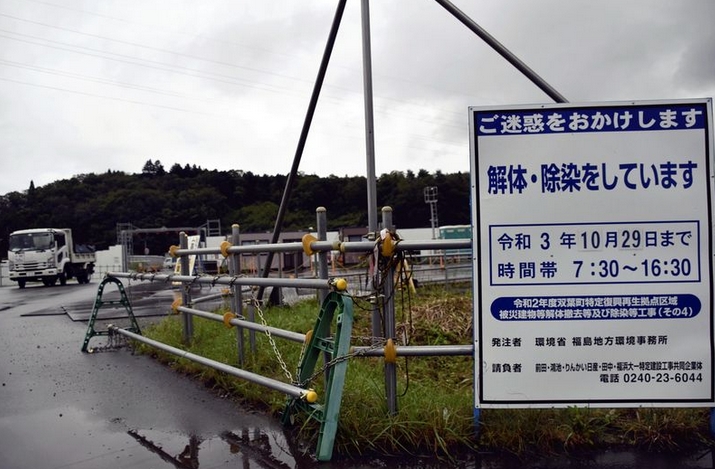

Soil separation and soil storage in Fukushima

Credits to Arkadiusz Podniesinsk

January 10, 12023

Today I visited the temporary waste dump adjacent to the power plant. I’ve been here several times, but this is the first time I’m with someone who can explain everything.

So, the temporary waste dump is a large area of 1600 hectares where contaminated soil from decontamination of areas from the whole prefecture goes. Before the disaster, most of these areas were cultivated fields, but there was also a fish processing plant, a school, a kindergarten and other public utilities. After the disaster, the entire area was bought by the government for the purpose of a landfill.

Currently, several plants have been built here that deal with sorting contaminated soil, ie. by separating wood, leaves, metals and other pollution (except radioactive contamination). The fire material is then burned and the ash is stored in special concrete containers. On the other hand, large, 15 meters high hills are dumped from the cleared soil, although when the grass grows they look more like small hills. Several layers of insulation are laid at the bottom of each mound and an irrigation system is being built that collects the flowing contaminated water to the treatment plant. Every mound has such an installation. At the end, I have attached a photo so that you can better understand the process described.

According to the name, the land will be stored here temporarily (up to 30 years) until a place for final storage is found. Research is currently underway on how to effectively reduce the amount of contaminated soil (volume reduction, recycling, new technologies) to minimize the amount of soil that will go to final landfill.

The whole thing is really impressive and above all works. It seems that the Japanese are seriously taking the issue of decontamination, although I personally don’t think that after 30 years such gigantic amounts of land should be transferred elsewhere again. Or at least I won’t see that anymore .

Our contaminated future

A rice field in Iitate, Fukushima prefecture, Japan, 2016.

is an assistant professor in the department of anthropology at Université Laval, in Quebec City, Canada. He is working on a book about the 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster, ‘Radioactive Governance: The Politics of Revitalization after Fukushima’.

As a farmer, Atsuo Tanizaki did not care much for the state’s maps of radioactive contamination. Colour-coded zoning restrictions might make sense for government workers, he told me, but ‘real’ people did not experience their environment through shades of red, orange and green. Instead, they navigated the landscape one field, one tree, one measurement at a time. ‘Case by case,’ he said, grimly, as he guided me along the narrow paths that separated his rice fields, on the outskirts of a small village in Japan’s Fukushima prefecture.

The author examines maps of radioactive contamination in Fukushima.

It was spring in 2016 when I first visited Tanizaki’s farm. The air was warm. The nearby mountains were thick with emerald forests of Japanese cedar, konara oak and hinoki cypress. A troop of wild red-faced monkeys stopped foraging to watch us as we walked by. And woven through it all – air, water, land, plants, and living bodies – were unseen radioactive pollutants. Almost everything now carried invisible traces of the 2011 meltdown at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant.

Tanizaki began taking measurements. With his Geiger counter, he showed me how radioactive elements were indifferent to the cartographic logic of the state. In some places, the radiation level dropped low, becoming almost insignificant. But here and there, beside a ditch or near a pond, the level was elevated dangerously high. Tanizaki called these areas ‘hot spots’ and they were scattered across the landscape, even within supposedly ‘safe’ zones on government maps. Contamination in Fukushima, he believed, was structured in a way that no state was prepared to solve.

A decade after the 2011 meltdown, the region remains contaminated by industrial pollution. Though attempts at removing pollutants continue, a new realisation has taken hold among many of Fukushima’s farmers: there’s no going back to an uncontaminated way of life.

Watching Tanizaki measuring industrial pollution in a toxic landscape neglected by the state, I began to wonder: is this a future that awaits us all?

As an anthropologist interested in contamination, Fukushima throws into sharp relief the question of what it means to live in a permanently polluted world. That is why I began coming to Japan, and spending time with farmers such as Tanizaki. I wanted to understand the social dynamics of this new world: to understand how radioactivity is governed after a nuclear disaster, and how different groups clash and collaborate as they attempt to navigate the road to recovery.

I expected to find social bonds pushed to breaking point. Stories of post-disaster collapse circulate in our collective consciousness – tales of mistrust, fear and isolation, accompanied by images of abandoned homes and towns reclaimed by plants and wildlife. And I found plenty of that. A sense of unravelling has indeed taken hold in rural Fukushima. Residents remain uncertain about the adverse health effects of living in the region. Village life has been transformed by forced evacuations and ongoing relocations. And state-sponsored attempts at revitalisation have been ineffective, or complete failures. Many communities remain fragmented. Some villages are still abandoned.

Farmers took matters into their own hands, embracing novel practices for living with toxic pollution

In Fukushima, I found a society collapsing under the weight of industrial pollution. But that’s only part of the story. I also found toxic solidarity.

Rather than giving up, Tanizaki and other farmers have taken matters into their own hands, embracing novel practices for living alongside toxic pollution. These practices go far beyond traditional ‘farming’. They involve weaving relationships with scientists, starting independent decontamination experiments, piloting projects to create food security, and developing new ways to monitor a changing environment. Among rice fields, orchards and flower beds, novel modes of social organisation are emerging – new ways of living from a future we will one day all reckon with.

But the story of toxic solidarity in Fukushima doesn’t begin among rice fields and farms. It begins under the Pacific Ocean, at 2:46pm on 11 March 2011. At that moment, a magnitude 9.0-9.1 earthquake off the coast of northeastern Japan caused a devastating tsunami that set in motion a chain of events leading to the meltdown of three reactors at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant. Soon, Fukushima would find its place alongside Three Mile Island and Chernobyl as an icon of nuclear disaster – and an emblem of the Anthropocene, the period when human activity has become the dominant influence on environmental change. As the reactors began to meltdown, pressure mounted in the power station’s facilities, leading to explosions that released dangerous radionuclides into the air, including caesium-134, caesium-137, strontium-90 and iodine-131. These isotopes, with lifespans ranging from days to centuries, blew across Fukushima and northeastern Japan. And as they accumulated, health risks increased – risks of cancers and ailments affecting the immune system. To protect the population, the Japanese state forced tens of thousands of citizens living near the reactors to evacuate.

Furekonbaggu, bags of contaminated soil, piled neatly in the Fukushima countryside.

At first, Tanizaki believed he had escaped the worst of the radiation because his village was not in the mandatory evacuation area. But when the wind carried radionuclides – invisible, tasteless, odourless – far beyond the government models, his village became one of the most contaminated areas in Fukushima. He learned he had been exposed to harmful radiation only when the government forced him to leave.

Tanizaki and other evacuated villagers were relocated to ‘temporary’ housing. As the months became years, Tanizaki longed to return to his life as a farmer. But what would he farm? His land had been irradiated, and no one wanted to eat food grown in radioactive topsoil. To help Fukushima’s rural citizens retrieve their farms, the Japanese government launched an official politics of revitalisation in Fukushima, investing trillions of yen to clean and decontaminate the region before repatriating evacuees. Part of the cleanup involved storing tainted topsoil in large black plastic bags known as furekonbaggu (literally ‘flexible container bags’), which were then stacked in piles throughout the countryside. To keep residents safe, the government also promised to track contamination through a monitoring system. At the time, the possibility of a pristine Fukushima seemed within reach.

In June 2015, after four years of forced evacuation, Tanizaki was finally allowed to return to his farm. But the decontamination efforts had failed. He and many others felt they had been returned to a region abandoned by the government. The landscape was now covered in millions of bags of radioactive topsoil – black pyramids of the Anthropocene – while the government waited for a permanent disposal site. Also, the plastic in some furekonbaggu had already broken down, spilling radioactive soil over freshly decontaminated land. The state’s monitoring efforts were equally inadequate. In Tanizaki’s village, the monitoring of airborne radiation produced measurements that were rarely precise enough to give a complete picture of shifting contamination. Villagers lived with constant uncertainty: is the garden contaminated? Are the trees behind the house safe? Are mushrooms in the forest still edible?

I saw dead sunflowers rooted in irradiated fields – withered emblems of dreams to retrieve Fukushima

For some, the uncertainty was too much. Tens of thousands relocated to other parts of Japan rather than returning. In 2010, the region registered 82,000 people whose main income came from farming. But by 2020, that number had fallen to around 50,000. Abandoned greenhouses and fields can still be found dotted across the landscape.

Withered sunflowers in irradiated fields.

Knowing that government efforts weren’t going to help, some returnees began to decontaminate their own villages and farms. There was hope that the region could be returned to its former uncontaminated glory. One proposed method involved planting sunflowers, which were believed to absorb radiation as they grew. Yellow flowers bloomed across the farmlands of Fukushima. However, the results were unsatisfactory. Even during my time in Japan, years after the disaster, I saw dead sunflowers still rooted in irradiated fields – withered emblems of early dreams to retrieve a pre-disaster Fukushima. I also witnessed decontamination experiments in rice paddies: farmers would flood their fields, and then use tools to mix the water with the irradiated topsoil below, stirring up and dislodging radioactive pollutants such as caesium. The muddy water was then pushed out of the field using large stiff-bristled brushes. This project also failed. Some paddy fields are still so contaminated they can’t grow rice that’s safe for human consumption.

These failures significantly affected the morale of Fukushima’s farmers, especially considering the importance of the region as a rice-growing capital. Once easy decontamination efforts failed, returnees were forced to ask themselves difficult questions about their homes, livelihoods and identities: what will happen if farming is impossible? What does it mean to be a rice farmer when you can’t grow rice? What if life has been irrevocably altered?

Even the mushrooms tasted different. One farmer, Takeshi Mito, told me he had learned to grow shiitake mushrooms on artificial tree trunks, since real trees were too contaminated to produce edible fungi. ‘Now the taste of the shiitake has changed,’ he mumbled, a strange sadness filling his voice. The ‘real’ trees had given the mushrooms a special flavour, just like ageing a whisky in a sherry cask. ‘Yeah,’ he said, pausing to remember. ‘They were good.’

A new reality was emerging. Farmers were learning to accept that life in Fukushima would never be the same. Small details are constant reminders of that transformation, like the taste of mushrooms, or the library in Tanizaki’s home, which is now filled with books on Chernobyl, nuclear power, radioactive contamination, and food safety. This is new terrain, in which everyone carries a monitoring device, and in which everyone must learn to live with contamination. A former way of life may be impossible to retrieve, and attempts at decontamination may have failed, but farmers such as Tanizaki are learning to form new relationships to their irradiated environment. They’re forging new communities, reshaping notions of recovery, and reimagining their shared identities and values. Contamination may appear to have divided Fukushima’s farmers, but it has also united them in strange and unexpected ways.

By the time the evacuees were allowed to return to their homes, government mistrust had become widespread. Official promises were made to Fukushima residents that a nuclear disaster was impossible. These promises were spectacularly broken when radiation spread across the region. A lack of information from state sources made things only worse, leading to a growing sense that the government was unable to provide any real solutions. Not trusting state scientists, but still wanting to know more about the invisible harm in their villages, farmers reached out to academics, nongovernmental organisations and independent scientists in the hope of better understanding radioactivity.

These new relationships quickly changed social life in rural communities, and brought an influx of radiation monitoring devices. Rather than asking for additional state resources (or waiting endlessly for official responses to questions), farmers worked with their new networks to track radiation, measuring roads, houses, crop fields, forest areas and wildlife. Everyone learned to use radiation monitoring devices, which quickly became essential bodily extensions to navigate a changed Fukushima. Many rural communities even began to use them to develop their own maps. I remember the walls of Tanizaki’s home being covered in printed images showing the topography of the local landscape, with up-to-date information about radiation often provided by farmers. Local knowledge of the environment, combined with the technical savoir faire of independent scientists, produced far more accurate representations of contamination than the state maps made by government experts.

Sharing the work of living with contamination provided a feeling of communal life that returnees had so missed

Thanks to these maps, Tanizaki now knew that radiation doses were higher at the bottom of a slope or in ditches (where radionuclides could accumulate, forming ‘hot spots’). He also knew that the trees outside someone’s home increased the radiation levels inside. Through this mapping work, many farmers developed a kind of tacit knowledge of radiation, intuitively understanding how it moved through the landscape. In some cases, it moved far beyond the colour-coded zones around the reactors, or even the boundaries of Fukushima itself. A major culprit of this spread has been inoshishi (wild boar), who eat contaminated mushrooms before migrating outside irradiated areas, where their highly contaminated flesh can be eaten by unsuspecting hunters. To address this problem, monitoring programmes were developed based on the knowledge of farmers, who were familiar with the feeding and migration patterns of wild boar. Once a delicacy, inoshishi have become what the anthropologist Joseph Masco calls ‘environmental sentinels’: a new way to visualise and track an invisible harm.

But monitoring is more than a pragmatic tool for avoiding harm. In many instances, it also became a means of forging new communities. After returning, farmers began to share their knowledge and data with scientists, gathering to talk about areas that need to be avoided, or holding workshops on radiation remediation. Ironically, sharing the work of living with contamination provided a feeling of communal life that returnees had so missed. Ionising radiation can ‘cut’ the chemical bonds of a cell. Based on the experiences of Tanizaki and other farmers, it can also create novel connections.

Many farmers told me of their amazement at the sheer diversity of people who had come to support the revitalisation efforts. And it wasn’t only former evacuees who were drawn into these new communities. It was also the volunteers who came to help from other parts of Japan. One scientist I spoke with, who specialised in radiation monitoring, ended up permanently moving to a village in Fukushima, which he now considers his hometown. There are many similar cases, and they’re especially welcome in the aftermath of a disaster that has deeply fragmented Fukushima’s rural community. Some farmers told me there were times when they would go weeks without speaking to anyone. Life in a polluted, post-disaster landscape can be lonely.

Monitoring might have helped residents avoid harmful radiation, but it didn’t necessarily help with farming. Often, the new maps revealed that crops grown in certain areas would fall beyond the official permissible thresholds for radiation in food. And so, farmers who could no longer farm were forced to develop alternatives. In collaboration with university scientists, some former rice farmers began growing silver grass as a potential source of biofuel that would provide energy for their region. ‘If we can’t grow food, we can at least make energy!’ one scientist told me.

Other farmers now use their irradiated fields to grow ornamental flowers. In the solarium of an elderly man named Noriko Atsumi, I saw rows of beautiful Alstroemeria flowers that are native to South America. When I visited in 2017, Atsumi was happy to talk about his flowers with me, and eager to show his solarium. ‘At the beginning,’ he told me, ‘it was really hard to try to grow flowers all alone, especially in these horrible conditions, but now I’m happy I did.’ Another elderly Fukushima farmer, Masao Tanaka, who lives alone on his farm, also dreamt of having a personal flower garden. I saw hundreds of narcissus flower bulbs he’d planted in a small field once used to grow commercial crops.

The flower gardens of Fukushima are an attempt to forge new relationships

For farmers such as Atsumi and Tanaka, growing flowers has become a new hobby. But ‘hobby’ is the key word here: Japan remains anxious about radiation in Fukushima produce, so most flowers are simply given away rather than sold. Though these ornamental flowers are not commodities like rice, they fall within an aesthetic of revitalisation. They’re little sprouts of precarious hope – the dream of a Fukushima that a new generation of farmers might one day call home. One village official explained this hope (and its complexities) to me like this:

I don’t know what kind of impression you have of our village. It used to be one of the top 10 prettiest villages in Japan. Now, there are 1.5 millionfurekonbaggu across it. They are left right next to paddy fields. Citizens are seeing these bags every day and asking themselves: ‘Can we really go back?’ They are being told that everything is safe, but when they see those bags, how can they be sure?

In a landscape of black bags, the flower gardens of Fukushima are an attempt to forge new relationships – an attempt to bring colours back to a post-disaster landscape and to the lives of those who live in it. Flowers represent a communal attempt to reshape the narrative of village life, which has been shadowed by tragedy. Flowers have allowed communities to make their villages beautiful again, and allowed farmers to take some pride in their decision to return to what many believed was a ‘ruined’ agricultural region.

On one trip to Fukushima, I visited a long plastic greenhouse where fire-red strawberries were being cultivated by a group of farmers and scientists. Inside, I saw rows of strawberries growing on the ground, fed by filtered water from a system of tubes. This watering system ran in and out of soil that was thick with pebbles, which a scientist told me were ‘volcanic gravels from Kagoshima’ on the other side of Japan, hundreds of kilometres away. They were using these gravels, he said, because the soil in Fukushima was ‘too contaminated to harvest safe products’. In fact, almost everything that the strawberries needed to grow, from the plastic greenhouse to the filtered water, had come from elsewhere. I couldn’t help asking: ‘Can you really say these strawberries came from Fukushima?’

One scientist working in the greenhouse seemed offended by my question. ‘We are using the safest technology in the world!’ he said. ‘It cannot be safer than that. The bad part is that people don’t write about this. All they write about are the plastic bags that you see everywhere!’

I was confused. I’d asked a question about provenance but was given an answer about safety. In the post-disaster landscape, safety had paradoxically become an integrated component of the products of Fukushima. The new agricultural products of Fukushima have become known not merely by the environment they grew in, but by the technologies that have allowed them to resist that environment. The scientist’s response showed some of the ways that Fukushima is embodying new values after the disaster. New products, like little red strawberries grown with imported soil, are becoming symbols of resilience, adaptation and recovery – part of the fabric of solidarity in a new Fukushima.

Toxic solidarity has been encouraged by the same organisations responsible for the disaster

But not everyone can share the embrace of toxic solidarity. In Tanizaki’s village, many young people have permanently left, wary of the health risks of residual radiation. These risks are especially concerning to new parents. During my fieldwork, I heard mothers complain about strange ailments their children experienced right after the disaster: chronic diarrhoea, tiredness, and recurrent nosebleeds that were ‘a very dark and unusual colour’. Concerns are not only anecdotal. After the disaster, thyroid cancers among children increased in Fukushima, which some believe was caused by exposure to iodine-131 from the meltdown. For some parents, leaving has been the only way to protect themselves and their children.

Complicating the binary between those working with or against contamination, toxic solidarity has been encouraged by the same organisations responsible for the disaster. For example, Japanese state ministries and nuclear-related organisations have increasingly encouraged returnees such as Tanizaki to become responsible for keeping their dose of radiation exposure as low as possible. In this way, safe living conditions become the responsibility of citizens themselves, as tropes of resilience are conveniently deployed by the state, and financial supports for disaster victims are gradually cut off. Those who refuse to participate in these projects have been labelled hikokumin (unpatriotic citizens), who hamper the revitalisation of Japan. What we find in this co-option is an unreflexive celebration of farmers’ resilience – a celebration that serves the status quo and the vested interests of state agencies, corporate polluters and nuclear lobbies. Through this logic, disaster can be mitigated, free of charge, by the victims themselves.

These blind celebrations of toxic solidarity only legitimise further polluting practices and further delegations by polluters. In a way, it is no different to the strategies of tobacco lobbies in the mid-20th century, who tried to market smoking as a form of group bonding, a personal choice or an act of freedom (represented by those many Marlboro Men who would eventually die from smoking-related diseases). While toxic solidarity can be applauded as a grassroots act of survival and creativity, it is also the direct result of broader structural patterns: the fact that polluting industries are often installed in peripheral, poor and depopulated regions; the repeated claims of government that toxic disasters can never happen; and the over-reliance on technological fixes that rarely solve social problems. When all else fails, it is always up to the ‘small’ people to pick up the pieces as best they can.

Contamination isn’t going away. Radiation will continue to travel through the landscape, pooling in rice paddies, accumulating in mushrooms and forests, and travelling in the bodies of migrating boar. Some areas remain so irradiated that they’re still bright red on the government maps. These are the prohibited ‘exclusion zones’, known in Japanese as kikan konnan kuiki (literally, ‘difficult-to-return zones’). They may not be reopened in our lifetimes.

One afternoon, someone from Tanizaki’s village took me to see the entrance to the nearby exclusion zone, which is blocked by a wide three-metre-long metal gate, barricades, and a guard. By the gate, in a small wooden cabin, a lonely policeman acted as a watchman. The gate, painted bright green, is supposed to separate people from an environment that is considered dangerous, but almost anybody can easily cross into the forbidden zone. Some farmers even have official access to the kikan konnan kuiki, so that they can check on the condition of their homes in the red zone. Cars and small pickup trucks go in and out, without any form of decontamination.

As I took a picture of the gate, the guard looked over and a farmer, perhaps worried I would get in trouble, came to explain: ‘He’s a foreigner you know, he just wants to see.’ It was forbidden for a non-Japanese person like me to enter the area. The same interdiction did not apply to locals. One Japanese citizen who had come with us was critical of this double standard: ‘The people of Fukushima are no longer normal people.’

In the post-disaster landscape, we can begin to see novel forms of community, resistance, agency and innovation

In the years since that day at the edge of the red zone, I have pondered this phrase many times. In the Anthropocene, when Earth has become permanently polluted – with microplastics, ‘forever chemicals’ and other traces of toxicity accumulating in our bodies – are any of us still ‘normal people’? The problems of Tanizaki and other Fukushima farmers will soon become everybody’s concern, if they haven’t already. How might we respond to this new reality?

The current mode of governing life in an age of contamination is built on a promise that we can isolate ourselves from pollution. This is a false promise. So-called decontamination measures in Fukushima are a crystal-clear example that this doesn’t work. There’s no simple way to ‘decontaminate’ our world from ubiquitous pollution: from mercury in sea life, endocrine disruptors in furniture, pesticide in breast milk, heavy metals in clothing, alongside an almost neverending list of other toxicants.

The experiences of Fukushima’s farmers show us how to navigate the uncharted, polluted seas of our age. Their stories show how new communities might express agency and creativity, even in toxic conditions. They also show how that agency and creativity can be co-opted and exploited by dubious actors. In the post-disaster landscape of rural Fukushima, we can begin to see the outlines of novel forms of community, resistance, agency and innovation that might shape our own future – a future that will hopefully be better, in which economic prosperity is not pitched against environmental wellbeing. In the end, these stories allow us to think about the kinds of toxic solidarity that we can nurture, as opposed to those that have historically been imposed on the wretched.

Someday, when we acknowledge we are no longer ‘normal’, Tanizaki’s story is one we must all learn to tell.

https://aeon.co/essays/life-in-fukushima-is-a-glimpse-into-our-contaminated-future

Japan: UN expert to assess Fukushima evacuees’ plight during official visit

21 September 2022

GENEVA (21 September 2022) – UN expert Cecilia Jimenez-Damary will visit Japan from 26 September to 7 October, to assess the human rights situation of internally displaced persons (IDPs), or evacuees, from the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster in 2011.

“Hundreds of thousands of people were displaced in the immediate aftermath of the disaster and tens of thousands remain as evacuees today, more than 10 years later,” said Jimenez-Damary, UN Special Rapporteur on the human rights of IDPs.

“By engaging with Government, evacuees, and other relevant stakeholders during the visit, I aim to foster collaborative, whole-of-society efforts to address the remaining barriers evacuees face in achieving durable solutions,” the expert said.

Jimenez-Damary will visit Tokyo and the prefectures of Fukushima, Kyoto, and Hiroshima. She will meet Government officials, UN bodies, academic experts, and human rights organisations, as well as civil society, IDPs and communities affected by internal displacement during her visit.

The UN expert will present her preliminary observations at the end of her visit on 7 October at a press conference, which will take place at 13:00 at the Japan National Press Club, 2-2-1 Uchisaiwaicho, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo 100-0011. Access to the press conference will be strictly limited to journalists.

A comprehensive report on the Special Rapporteur’s visit will be presented to the Human Rights Council in June 2023.

ENDS

Ms. Cecilia Jimenez-Damary was appointed Special Rapporteur on the human rights of internally displaced persons by the United Nations Human Rights Council in September 2016. A human rights lawyer specialized in forced displacement and migration, she has over three decades of experience in NGO human rights advocacy. Her mandate, which covers all countries, has been recently renewed by resolution 50/6 of the Human Rights Council.

As a Special Rapporteur, she is part of what is known as the Special Procedures of the Human Rights Council. Special Procedures, the largest body of independent experts in the UN Human Rights system, is the general name of the Council’s independent fact-finding and monitoring mechanisms that address either specific country situations or thematic issues in all parts of the world. Special Procedures’ experts work on a voluntary basis; they are not UN staff and do not receive a salary for their work. They are independent from any government or organization and serve in their individual capacity.

Read the UN Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement

UN Human Rights country page: Japan

Number of evacuees from Fukushima Prefecture due to the nuclear power plant accident

August 23, 2022

On August 23, three groups of evacuees from Fukushima Prefecture requested the Reconstruction Agency not to exclude approximately 6,600 people from the number of evacuees from outside of Fukushima Prefecture due to the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant accident, because their whereabouts cannot be confirmed. The reduction in the number of evacuees in the statistics may lead to a trivialization of the damage caused by the nuclear power plant accident.

The Reconstruction Agency compiles the number of evacuees based on the information that evacuees have reported to the municipalities where they have taken refuge. In some cases, such as when evacuees move away without notifying the local government, their whereabouts are lost. As a result of the survey conducted since last September, approximately 2,900 people’s whereabouts are unknown, and approximately 2,480 people have moved without notifying the municipality. In addition, a total of 6,604 people will be excluded from the evacuee statistics, including approximately 1,110 people who answered “will not return” in the survey.

As of April, the number of out-of-prefecture evacuees was approximately 23,000, a decrease of more than 3,300 from January, as reports continue to follow this policy. The number is expected to continue to decrease as each municipality works to correct the situation.

The request was made on this day by the National Association of Evacuees for the “Right to Evacuation” and others. Seiichi Nakate, 61, co-chairman of the association and an evacuee from Fukushima City to Sapporo City, said, “Even though I no longer have the intention to return, I am aware that I am an ‘evacuee. I cannot allow myself to be excluded by the government.” He handed the written request to a Reconstruction Agency official. The official explained that the exclusion would be made in order to match the actual situation of the evacuees, but that it would not affect the support measures.

At the press conference, Nakate said, “Eleven years have passed since the accident, and the number of official support measures at the evacuation sites is decreasing every year. The evacuee statistics are the basis for all support measures, and I am concerned that they may lead to further reductions in support in the future. (Kenta Onozawa)

https://www.tokyo-np.co.jp/article/197673?fbclid=IwAR1Om2iDjG_pTgRouOTIf-Ji0p18kJC6R9bkXkJxDBKx66RYKjZkt14L3_Q

Fukushima Thyroid Examination October 2021: 221 Surgically Confirmed as Thyroid Cancer Among 266 Cytology Suspected Cases

Overview

On October 15, 2021, the 43rd session of the Oversight Committee for the Fukushima Health Management Survey (FHMS) convened online and in Fukushima City, releasing a new set of results (data up to June 30, 2021) from the fourth and fifth rounds of the Thyroid Ultrasound Examination (TUE). The fifth-round data reported this time includes the confirmatory examination results. In addition, a corrected version of the results was released for the Age 25 Milestone Screening originally reported in July 2021.

The 43rd session was the first session of a new two-year term (August 2021-July 2023) for 18 committee members, including 6 new members. (Regrettably, a long-time committee member Fumiko Kasuga, who steadfastly advocated for release of more clinical information as well as inclusion of feedbacks from participants and their families, is no longer included.) A roster for the Thyroid Examination Evaluation Subcommittee was also released, but there was no change. It was revealed that there was no target date for the release of an interim summary for the third round.

At this time, an official English translation is available up to the 40th session of the Oversight Committee on the website for the Radiation Medical Science Center of the Fukushima Health Management Survey (RMSC/FHMS). The final results of the third round, released at the 39th session in August 2020, is finally available in English on pages 2-20 of this report.

Highlights

- The fourth round: 3 new cases diagnosed as suspicious or malignant, and 2 new surgical cases.

- The fifth round: 3 new cases diagnosed as suspicious or malignant, and 1 new surgical case

- Total number of suspected/confirmed thyroid cancer has increased by 6 to 266: 116 in the first round (including a single case of benign tumor), 71 in the second round, 31 in the third round, 36 in the fourth round, 3 in the fifth round, and 9 in Age 25 Milestone Screening.

- Total number of surgically confirmed thyroid cancer cases has increased by 3 to 221 (101 in the first round, 55 in the second round, 29 in the third round, 29 in the fourth round, 1 in the fifth round, and 6 in Age 25 Milestone Screening,

The latest overall results including the “unreported” and cancer registry cases

Please refer to the previous post regarding details of “unreported” cases and cancer registry data.

Official count, as reported in the summary document shown in the next section, is 266 suspected/confirmed and 221 surgically confirmed thyroid cancer cases. An addition of more recent “unreported” cases as well as “outside” cases discovered in cancer registry makes the count a little more complete with 325 cytologically suspected/confirmed and 264 surgically confirmed cancer cases. It should be noted that the actual number of cases is likely more than these as no exhaustive investigation has been and will be conducted by FMU to fully report all the cancer cases discovered outside the framework of the FHMS-TUE.

Summary on the current status of the TUE

A six-page summary of the first through fifth rounds as well as the Age 25 Milestone Screening, “The Status of the Thyroid Ultrasound Examination Results,” lists key findings from the primary and confirmatory examinations as well as the surgical information.

Below is an unofficial translation of this summary which is not officially translated.

#43 Status of the Thyroid Ultrasound Examination Results (October 15, 2021) by Yuri Hiranuma on Scribd

Is contaminated soil from the nuclear accident waste? A valuable resource? Ask the Experts

April 8, 2022

Fukushima: The delivery of contaminated soil from the decontamination process following the accident at TEPCO’s Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant to an interim storage facility was largely completed last month. The law stipulates that the final disposal of the contaminated soil must be outside the prefecture, but no one has yet found a place to accept the soil. We asked Tsunehide Chino, an associate professor at Shinshu University and an expert on radioactive waste administration, about the legal status of the facility and how the contaminated soil should be “recycled.

◇ ◇Associate Professor Tsunehide Chino of Shinshu University

–The delivery of contaminated soil to the interim storage facility was largely completed at the end of March.

The law states that “necessary measures shall be taken for final disposal outside the prefecture by 2045. That is quite a delicate phrase.”

–prefectures can argue that the promise to remove the materials out of the prefecture should be honored.

The problem has taken on another dimension since the law clearly states this. For example, the government signed a ‘letter of commitment’ with the governor of Aomori Prefecture regarding the final disposal of high-level radioactive waste from Rokkasho Village in Aomori Prefecture outside the prefecture. It is not a law.”

The law is not wrong, and neither the prefectural governor nor the heads of local governments have any choice but to talk about their positions, even if they don’t believe that the cargo will be removed in 45 years. It has become difficult for them to express their true feelings.”

–The national government has a policy of recycling contaminated soil with radiation levels below 8,000 becquerels per kilogram, as final disposal of the entire amount of contaminated soil is difficult.

There is no legal basis for recycling. If the prefectural governor and others say that the contaminated soil in the interim storage facility will be taken out of the prefecture because it is clearly stated in the law, then it makes sense to discuss and make the recycling of contaminated soil into a law.

–How was the standard for recycling (8,000 becquerels) determined?

In 2005, the government established a clearance system that allows radioactive waste to be disposed of as normal waste, and set the standard at 0.01 millisievert per year as a level of radiation that has negligible effects on the human body when it is recycled or landfilled. This is equivalent to 100 becquerels of radiation per kilogram. After the nuclear accident, however, the government relaxed the standard for disposal to 1 millisievert per year. The amount of radiation that we calculated backwards from that is 8,000 becquerels per kilogram.

–So you want to apply this to soil that is to be reclaimed?

The government has positioned reclamation as part of the disposal process. The government has taken the liberty of changing the rules to say that although it is disposal, it only needs to meet the 1 millisievert per year requirement.

If it’s disposal, it has to meet clearance standards. The repository has been operated in accordance with these standards. But, for example, it is estimated that it would take 160 years of natural attenuation for contaminated soil with a level of 5,000 becquerels per kilogram to meet the criteria for disposal. It is unlikely that the facilities where the soil will be recycled will be maintained and managed for that long. The government’s policy is irresponsible.”

–The government says that the soil to be reclaimed is a “precious resource.

The Basic Policy for Fukushima Reconstruction and Revitalization approved by the cabinet in July 2012 clearly states that contaminated soil in the prefecture will be finally disposed of outside the prefecture 30 years after interim storage begins, and the idea that soil is a resource was written into law in December 2002.

In waste administration, waste is anything that is no longer needed. If it can be used or sold, it is a resource. So we ask the Ministry of the Environment, ‘So you give away soil for public works projects for a fee? We tell them that there is no such thing as “reverse compensation,” in which we pay for the soil when we give it to them. But they are not very understanding.

–The legalities regarding the handling of contaminated soil are unclear, and the standards are difficult to understand. How do you plan to resolve the situation where residents have no say in the matter?

The situation cannot be solved by creating a law. The first step is for the government and TEPCO to explain firmly that it will be more difficult than expected to return the living environment in the hard-to-return zones and other areas to the state it was in before the nuclear accident. The best way to restore the trust that has been lost over the past decade is for both sides to understand the bitter reality.

◇ ◇ ◇

Tsunehide Chino was born in 1978 in Tokyo. D. (Policy Science) from Hosei University’s Graduate School of Social Sciences. associate professor at Shinshu University’s Faculty of Humanities since 2014. has been researching issues such as radioactive waste for nearly 20 years, mainly in Rokkasho Village, Aomori Prefecture. He is also the coordinator of the Nuclear Waste Subcommittee of the Citizens Commission on Atomic Energy.

https://www.asahi.com/articles/ASQ476QGRQ1DUGTB001.html?fbclid=IwAR2vajn4ZWVmJU2VZd3Er_NwclfBJYHiB02ZsPpSqyuCJD_8QKgofwdCDGI

Powerful Japan earthquake strikes off coast of Fukushima, killing four

Tsunami warning cancelled after quake cut power to 2m homes and damaged some buildings

March 17, 2022

A powerful 7.4 magnitude earthquake struck off the coast of Fukushima in north-east Japan on Wednesday evening, leaving four dead, and plunging more than 2m homes in the Tokyo area into darkness.

The region was devastated by a deadly 9.0 quake and tsunami 11 years ago that also triggered nuclear plant meltdowns, spewing massive radiation that still makes some parts uninhabitable.

The Japan Meteorological Agency later lifted its low risk tsunami advisory issued along the coasts of Fukushima and Miyagi early Thursday. Tsunami waves of 30cm (11in) reached shore in Ishinomaki, which lies about 390km (242 miles) north-east of Tokyo. The agency upgraded the magnitude of the quake to 7.4 from the initial 7.3.

Japan’s prime minister, Fumio Kishida, said four people had died and that the government would be on high alert for the possibility of further strong tremors over the next two to three days.

At least 107 people were reported injured, several of them seriously, with 4,300 households still without water by mid-morning. Residents of one Fukushima city formed a long queue in a car park to fill up plastic tanks with water for use at home.

NHK footage showed broken walls of a department store building fell to the ground and shards of windows scattered on the street near the main train station in Fukushima city, about 60km (36 miles) from the coastline. Roads were cracked and water poured out from pipes underground. Footage also showed furniture and appliances smashed to the floor at apartments in Fukushima.

The Tokyo Electric Power Company Holdings, which operates the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant where the cooling systems failed after the 2011 disaster, said workers found no abnormalities at the site, which was in the process of being decommissioned.

Japan’s Nuclear Regulation Authority said a fire alarm went off at the turbine building of No 5 reactors at the Fukushima Daiichi but there was no actual fire. Water pumps for the spent fuel cooling pool at two of the four reactors at Fukushima Daini briefly stopped, but later resumed operation. Fukushima Daini, which survived the 2011 tsunami, is also set for decommissioning.

Manufacturers, including global chipmaker Renesas Electronics and automaker Toyota, said they were trying to gauge the potential damage to their facilities in the region.

The Japan Meteorological Agency said the quake hit at 11.36pm at a depth of 60km (36 miles) below the sea.

Japan’s Air Self-Defence Force said it sent fighter jets from the Hyakuri base in Ibaraki prefecture, just south of Fukushima, for information gathering and damage assessment.

More than 2.2m homes were temporarily without electricity in 14 prefectures, including the Tokyo region, but power was restored at most places by the morning, except for some homes in the hardest hit Fukushima and Miyagi prefectures, according to the Tohoku Electric Power Co which services the region.

The quake shook large parts of eastern Japan, including Tokyo, where buildings swayed violently.

Advertisement

East Japan Railway Co said most of its train services were suspended for safety checks. Some local trains later resumed service.

Many people formed long lines outside of major stations while waiting for trains to resume operation late Wednesday, but trains in Tokyo operated normally Thursday morning.

A Tohoku Shinkansen express train partially derailed between Fukushima and Miyagi due to the quake, but nobody was injured, Kishida said.

He told reporters that the government was assessing the extent of damage and promised to do its utmost for rescue and relief operations.

Chief cabinet secretary Hirokazu Matsuno said authorities were scrambling to assess damage. “We are doing our utmost in rescue operations and putting people’s lives first,” he said.

Britain lifting post-Fukushima restrictions on Japan food imports

Dec 11, 2021

The British government has started the process to lift import restrictions on farm products from Japan, a measure imposed in the wake of the Fukushima nuclear disaster, potentially clearing the hurdles for such imports as early as next spring, the farm ministry has said.

In its assessment of the possible health risks from Japanese food imports, Britain has concluded that removing the import restrictions would not affect consumers in the country.

As part of the domestic procedure, Britain will solicit public comments on the policy change by February before making a formal decision, the Japanese ministry of agriculture, forestry and fisheries said Friday.

A total of 23 farm products such as mushrooms, bamboo shoots and bonito from Fukushima and eight other prefectures are currently subject to the import restrictions, requiring proof of having passed a check for radioactive materials when these products are shipped into Britain.

The eight prefectures are Miyagi, Yamagata, Ibaraki, Gunma, Niigata, Yamanashi, Nagano and Shizuoka.

If the restrictions are lifted, the certificates of origin now required for these farm products harvested or processed in Japanese prefectures other than the nine will also become unnecessary for exporting to Britain.

According to the farm ministry, the export value of Japanese farm products to Britain amounted to ¥4.5 billion ($39.7 million) in 2010. But it fell to ¥3.7 billion in 2012 following the nuclear meltdown at the Fukushima No. 1 plant in March the previous year.

Japanese farm exports to Britain recovered to ¥5.6 billion in 2020.

Japan plans to continue urging the removal of import restrictions by the 13 countries and regions such as China and South Korea that maintain them due to safety concerns.

The United States lifted its import restrictions on Japanese farm products in September, while the European Union eased part of its restrictions in October.

https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2021/12/11/national/uk-japan-fukushima-food-restrictions/

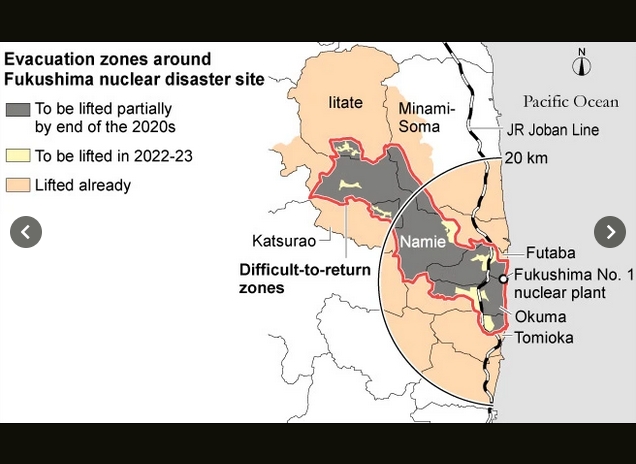

More evacuation orders to be lifted in Fukushima for some areas

September 24, 2021

Shrouded in trees and weeds as tall as people, his old house rests quietly in a difficult-to-return zone in the Tsushima district of Namie, Fukushima Prefecture, only some 30 kilometers from the hobbled nuclear plant.

“I can finally see light at the end of the tunnel, although there will likely be a race against the clock of my lifetime,” said Yoshito Konno, 77. “I wish to be comfortably back in my hometown while I am still healthy enough to be moving around.”

The central government announced it will lift evacuation orders by the end of the decade for residents who wish to return to their homes in the last remaining difficult-to-return zones around the Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant.

The new policy was approved at a joint meeting at the end of August by the Reconstruction Promotion Council and the Nuclear Emergency Response Headquarters.

But the government has no prospect of totally lifting evacuation orders for all the difficult-to-return areas as the new policy is expected to cover only limited areas.

Konno’s home community had 262 residents from 80 households prior to the 2011 nuclear disaster.

About 45 of them, mostly advanced in age, have since died.

“Those who died while separated from their hometown must have felt so frustrated and let down,” he said. “The central government and the town government should take action as soon as possible in line with the newly approved plan.”

Currently, areas where about 22,000 residents used to live remain designated as difficult-to-return zones.

This latest decision covers sparsely populated areas which are outside the areas designated for earlier lifting and once home to some 8,000 people, who previously had little hope of ever returning given the absence of a plan for them.

Some of the more populated areas had been designated as reconstruction bases where evacuation orders will be lifted by spring 2023.

Local communities had been pressing the central government to come up with a plan for lifting the evacuation orders in those undesignated areas. The government has committed to fund cleanups and lift evacuation orders on a limited basis, when requested by the locals.

For people like Konno, the news came as a relief.

But more than a decade since the disaster, others have mixed feelings about the prospect of one day returning after finding new lives and livelihoods in the communities to which they have evacuated to.

MOST WON’T RETURN

A survey taken by the Reconstruction Agency in fiscal 2020 showed that in the four towns that contain part of the difficult-to-return zones, only about 10 percent said they wished to return.

About 50 to 60 percent of respondents from each of those towns said they did not want to return.

Kazuharu Fukuda, 50, president of a local construction company and evacuee from the town of Futaba, said he will not be returning home any time soon because he now resides and works in another town.

The central government’s plan to decontaminate areas where cleanup is necessary to allow people to return has not impressed Fukuda.

“Even if I were to return, the land plots next to mine would remain contaminated with high radiation levels and with everything left in a dilapidated state,” he said. “How could I take up residence in such a place? I want the central government to clean up all the areas and restore them to their original state before letting us decide whether to return.”

Under the new plan, which was presented by Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga during the joint meeting, residents of the areas in question will be surveyed.

After that, the surroundings of the homes of those who wish to return will be decontaminated, and the government will develop key infrastructure to facilitate their return.

There is no prospect for evacuation orders to be completely lifted in those areas because the decontamination work will be done only in limited areas at the request of those who wish to return.

The decontamination process will be funded by two special central government accounts: one designated for rebuilding from the Great East Japan Earthquake, tsunami and Fukushima nuclear disaster of 2011; and another designated for energy policy measures, financed by revenues from electricity rates.

The difficult-to-return zones straddle six towns and villages in Fukushima Prefecture.

Some areas in those zones, including the surroundings of town halls, village offices and residential districts, have been designated “Specified Reconstruction and Revitalization Bases” by the central government.

The goal is to lift the evacuation orders in those places sometime between 2022 and the spring of 2023.

The central government is funding cleanup, construction of public housing complexes for disaster survivors and other work currently under way in these locations.

The areas outside the “specified bases” account for more than 90 percent of all the landmass of the difficult-to-return zones and slightly less than 40 percent of the population. Cleanup and other related work will only be conducted in those outside areas after considering whether the residents are expected to return.

Local governments had called on the central government to set a date to lift all the difficult-to-return zones so residents outside the designated reconstruction bases will not be left behind.

The central government has so far lifted evacuation orders for areas home to about 45,000 people. Only about 14,000 of those residents–about 30 percent–have returned to their home communities, although the government has spent some 3 trillion yen ($27 billion) on cleaning up those areas alone.

The government remains skeptical that large-scale decontamination will be effective for post-disaster rebuilding, so it has decided to clean up only limited areas based on requests.

Fukushima aims to attract new residents

September 20, 2021

FUKUSHIMA – The central and local governments have begun encouraging people from outside Fukushima Prefecture to move into areas surrounding Tokyo Electric Power Company Holdings, Inc.’s Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant, hoping that new residents will revive the areas.

The central government plans to lift evacuation orders in all areas categorized as difficult-to-return zones so that residents wishing to return to their homes can do so within the 2020s. However, in areas where such an order has already been lifted, residents have been slow to return.

300 newcomers sought

I’ve long wanted to contribute to the reconstruction of Fukushima, said Daisuke Yamamoto, 49, an engineer who moved from Sapporo to the city of Tamura, Fukushima Prefecture, in August.