Australia’s State governments fight each other to avoid having to store nuclear wastes

Expect weapons-grade NIMBYism as leaders fight over where to store AUKUS nuclear waste

Given that proposals for even low-level nuclear waste sites have been rejected by communities, who is going to take on the radioactive waste created by our new military pact?

ANTON NILSSON, FEB 01, 2024, Crikey,

here should Australia store the waste created by its investment in nuclear-driven submarines? It’s a question no-one knows the answer to yet — although we do know a couple of places where the radioactive waste won’t be stored. As the search for a solution continues, expect politicians to try to kick the radioactive can further down the road — and expect some weapons-grade NIMBYism from state and territory leaders if they’re asked to help out.

In August last year, plans to build a new nuclear waste storage facility in Kimba in South Australia were scrapped. As Griffith University emeritus professor and nuclear expert Ian Lowe put it in a Conversation piece, “the plan was doomed from the start” — because the government didn’t do adequate community consultation before deciding on the spot.

Resources Minister Madeleine King acknowledged as much when she told Parliament the government wouldn’t challenge a court decision that sided with traditional owners in Kimba, who opposed the dump: “We have said all along that a National Radioactive Waste Facility requires broad community support … which includes the whole community, including the traditional owners of the land. This is not the case at Kimba.”

Kimba wasn’t even supposed to store the high-level waste that will be created by AUKUS submarines — it was meant to store low-level and intermediate-level waste, the kind generated from nuclear medicine, scientific research, and industrial technologies. As King told Parliament, Australia already has enough low-level waste to fill five Olympic swimming pools, and enough intermediate-level waste for two more pools.

Where the waste from AUKUS will go is a question without answer. Deputy Prime Minister Richard Marles said in March last year the first reactor from a nuclear-powered submarine won’t have to be disposed of until the 2050s. He added the government will set out its process for finding dump sites within a year — which means Marles has until March this year to spill the details.

“The final storage site of high-level waste resulting from AUKUS remains a mystery,” ANU environmental historian Jessica Urwin told Crikey. “Considering the historical controversies wrought by low- and intermediate-level waste disposal in Australia over many decades, it is hard to see how any Australian government, current or future, will get a high-level waste disposal facility off the ground.”

In his comments last year, Marles gave a hint as to the government’s intentions: he said it would search for sites “on the current or future Defence estate”.

One such Defence estate site that’s been the focus of some speculation is Woomera in South Australia. “A federal government decision to scrap plans for a nuclear waste dump outside the South Australian town of Kimba has increased speculation it will instead build a bigger facility on Defence land at Woomera that could also accommodate high-level waste from the AUKUS submarines,” the Australian Financial Review reported last year.

Urwin said such a proposal could trigger local opposition as well.

Due to Woomera’s proximity to the former Maralinga and Emu Field nuclear testing sites, and therefore its connections to some of the darkest episodes in Australia’s nuclear history, communities impacted by the tests and other nuclear impositions (such as uranium mining) have historically pushed back against the siting of nuclear waste at Woomera,” she said.

Australian Submarine Agency documents released under freedom of information laws in December last year show there is little appetite among state leaders to help solve the conundrum.

A briefing note to Defence secretary Greg Moriarty informed him that “state premiers (Victoria, Western Australia, Queensland, and South Australia) [have sought] to distance their states from being considered as potential locations”. ………………………………………………….. more https://www.crikey.com.au/2024/02/01/aukus-nuclear-waste-storage-australia/

Japan should consider shifting to direct disposal of nuclear waste

Vitrified radioactive waste in the storage facility at Rokkasho, Aomori Prefecture

February 20, 2023

The Kishida administration has unveiled a policy initiative to deal with high-level radioactive waste from nuclear power plants through “united government-wide” efforts.

The government plans to step up its efforts to find a local government willing to host a final disposal site for nuclear waste. The government should naturally assume the responsibility of dealing with this problem, but it should not pressure local governments to host a disposal facility.

According to the draft revision to the basic policy for tackling the problem, which was announced earlier in February, the government will set up a “council for discussions” with interested local governments to discuss the challenges and possible policy responses.

Based on these talks, the national government will propose in stages to local administrations to accept a survey for a disposal site.

Under the current basic policy, the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry published in 2017 a map of the nation showing potential areas for locating a deep geological disposal site. At this site, spent fuel would be buried in engineered facilities 300 or more meters below ground level.

The initial phase of assessing two municipalities in Hokkaido for their suitability to host such a disposal facility began three years ago. The first stage of the process, called “bunken chosa” (literature survey), involves reviews of geological maps and research papers concerning local volcanic and seismic hazards and other related factors.

No other municipalities have yet to volunteer for undertaking this process.

High-level radioactive waste from spent nuclear fuel, however, is not the only kind of nuclear waste that must be disposed of. Other types of nuclear waste include materials from decommissioned reactors and melted “fuel debris” from the stricken Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant, which has been left untreated.

One inconvenient fact for supporters of nuclear power generation is that no solution has been found as to where all these kinds of nuclear waste should be disposed of.

At nuclear power plants across the nation, growing amounts of spent nuclear fuel are fast filling up the spent fuel pools within the premises, with not much room left. Operating nuclear plants will eventually start generating spent fuel that cannot be stored anywhere.

The government’s move to accelerate its program to build a final disposal site is aimed at defusing criticism about its policy shift toward expanding nuclear power generation by signaling a willingness to tackle these policy challenges.

Since there is already a large amount of spent nuclear fuel, a disposal site is clearly necessary. A broad consensus on the issue should be built through debate involving the entire nation, including citizens of major cities who consume huge amounts of electricity.

It would be better for such a debate to be held at an independent organization that is separated from the industry ministry, which promotes the use of atomic energy. The law for regulating measures related to the final disposal of radioactive waste should be reviewed for necessary revisions.

Since Article 1 of the law refers to the “proper use of nuclear power,” the construction of a final disposal facility could justify the long-term use of nuclear power.

That would mean nuclear plants will keep producing spent fuel for decades to come. This prospect will make local communities that may host the disposal facility concerned about the possibility that radioactive waste may be brought to the site without end.

The law is based on the assumption that a nuclear fuel reprocessing system to recover plutonium and uranium from spent nuclear fuel to be reused in reactors will be established.

Northern Europe and many other countries with an advanced program to deal with radioactive waste have adopted the approach known as direct disposal, a management strategy where used nuclear fuel is disposed of in a deep underground repository, without any recycling.

Instead of adhering to the now unworkable program to establish a fuel recycling system, the government should designate direct disposal as a realistic option.

This is the time to fundamentally rethink the law, which was enacted more than two decades ago without much serious debate, taking into consideration the experiences of the Fukushima nuclear disaster.

Righting shoddy nuclear waste storage site to cost Japan 36 bil. yen (280 million US$)

File photo taken in October 2021 shows the Japan Atomic Energy Agency’s Tokai Reprocessing Plant in Tokai, Ibaraki Prefecture, eastern Japan

Jan 15, 2023

The Japan Atomic Energy Agency estimates that it will cost taxpayers 36.1 billion yen ($280 million) to rectify the shoddy storage of radioactive waste in a storage pool at the Tokai Reprocessing Plant, the nation’s first facility for reprocessing spent nuclear fuel, an official said Sunday.

Around 800 containers of transuranic radioactive waste, or “TRU waste,” were dropped into the pool from 1977 to 1991 using a wire in the now-disused plant in Tokai, a village in Ibaraki Prefecture northeast of Tokyo. They emit high levels of radiation.

The waste includes pieces of metal cladding tubes that contained spent nuclear fuel, generated during the reprocessing process. The containers are ultimately supposed to be buried more than 300 meters below surface.

The agency has estimated that 19.1 billion yen will be needed to build a new storage facility for the containers, and 17 billion yen for a building that will cover the storage pool and the crane equipment to grab containers.

The 794 containers each are about 80 centimeters in diameter, 90 cm tall and weigh about 1 ton, with many lying on their sides or overturned in the pool. Some have had their shape altered by the impact of being dropped.

The containers were found stored in the improper manner in the 1990s. While the agency said the storage is secure from earthquakes and tsunamis, it has nonetheless decided to improve the situation.

The extractions have been delayed by about 10 years from the original plan and are expected to begin in the mid-2030s.

The Tokai Reprocessing Plant was the nation’s first plant that reprocessed spent fuel from nuclear reactors to recover uranium and plutonium. Between 1977 and 2007, about 1,140 tons of fuel were reprocessed. The plant’s dismantlement was decided in 2014 and is expected to take about 70 years at a cost of 1 trillion yen.

Nuclear waste: from Bure in the Meuse, France to Japan, opponents of the burial unite

In Bure, in the Meuse, the Cigéo project for the burial of long-lived nuclear waste has been recognized as being of public utility. Opponents are calling on the Japanese to mobilize against a similar project on the island of Hokkaido.

Opponents of the Bure nuclear waste burial project have lent their support to the inhabitants of Suttsu, Japan, where a similar project is under study.

Ouest-France Alan LE BLOA. Published on 03/11/2022

On the borders of the Meuse and Haute-Marne regions, the Cigéo project for a nuclear waste burial center in Bure has been declared to be in the public interest. The decree, published on Friday, July 8, authorizes the National Agency for Radioactive Waste Management (Andra) to acquire the land needed for the surface installations, as well as the land located above the galleries. This means about 3,500 hectares, which can be expropriated if necessary.

85,000 m3 of radioactive waste

The aim of the project is to bury 85,000 cubic meters of long-lived high-level and intermediate-level radioactive waste from France’s nuclear power plants 500 meters underground by at least 2080. This decisive step, since the launch of research on site twenty years ago, has rekindled tensions. Some thirty associations and residents have filed an appeal with the Council of State to challenge the decision. A message relayed to Japan

On September 16, EELV and LFI parliamentarians gave their political support to the opponents’ action… which is becoming international. In a message relayed to Japan, they have, in fact, sent their support to the inhabitants of the village of Suttsu, opposed to the project of burying radioactive waste in the subsoil of the island of Hokkaido, in the north of the archipelago. The burial projects “are devastating for our territories and represent economic brakes for their future. No one wants to live next to a radioactive repository. The promises of development are lies intended to make the projects acceptable”, they write, condemning “the lack of transparency of the authorities”.

In the meantime, in Bure, an observatory for the health of local residents is being set up. Its objective? To monitor the physical and psychological health of residents within a 25 km (6,000 people in 180 municipalities) and 50 km (340,000 people in 679 municipalities) perimeter. Some 900 people, selected at random, are to be interviewed to assess their health.

Nuclear waste: in Japan, a sensitive project in an earthquake-prone region

On the island of Hokkaido, a contested project plans to bury 19,000 tons of radioactive waste 300 m underground. In a region subject to the risk of earthquakes.

Yugo Ono, geologist and professor emeritus at the University of Hokkaido, considers that it is risky to bury radioactive waste in an area subject to seismic movements.

Ouest-France Johann FLEURI. Published on 03/11/2022 at 06h30

On the island of Hokkaido, Numo is carrying out stage 1 of the investigation, which began in 2020. The radioactive waste management company is studying the location, soils, seismic history of the area and calculating budgets. Residents and the city council will be asked to vote on whether to proceed with the project and move to Phase 2. The vote, scheduled for November, has been postponed.

Stored for over a thousand years

The 19,000 tons of nuclear waste that could eventually be buried on site, between 300 m and 3 km below the surface of the ground, are extracts of liquid waste, which after several treatments, remain highly radioactive and must be stored for more than a thousand years, to no longer present a danger to humans. The burial project, the first of its kind in the archipelago, consists of placing them in stainless steel tubes, so that they can be stored as vitrified waste. Numo plans to store 40,000 of these containers underground.

Soil and water table

An underground project that seems risky in a country subject to earthquakes. At Numo, we believe that “the degree of danger is under control”. In the event of a major earthquake, “the containers will follow the movement of the earth”. But Yugo Ono, a geologist and professor emeritus at Hokkaido University, does not share this opinion. “Buried, the waste could pollute the soil and groundwater in the event of a strong earthquake,” he says.

Risks

“The geology of the region, composed of volcanic rocks, is unsuitable for such a project, says the scientist. The soil is very affected by seismic activity. In the case of a major earthquake in Suttsu, “the radioactivity will spread into the water table,” he says. The waste would be stored at a depth of 300 meters, while “seismic activity can be felt up to 10 kilometers down.” Under pressure, the expert is certain: “The tanks will break.”

Another method

Rather than burial, “the only method of storing radioactive waste for Japan today is in steel containers, covered with 2 meters of concrete, within the walls of nuclear power plants. According to Yugo Uno, “this is the safest method, which we master best and it is not so expensive”. But this system requires that the containers be changed every fifty years at the most because the steel will be attacked by radioactivity. “Every twenty years would be better for maximum safety.”

REPORT. In Suttsu, Japan, the inhabitants do not want nuclear waste

At a time when Japan is announcing the restart of seventeen nuclear reactors by 2023, the question of radioactive waste management arises. In Suttsu, a landfill project is under study, to the great despair of the inhabitants.

Miki Nobuka, 50 years old, says she learned that the project of nuclear waste burial was validated while she was buying her bread.

Ouest-France Johann FLEURI. Published on 03/11/2022

“We don’t want our village to become a garbage dump,” say Kazuyuki Tsuchiya and his wife Kyoko. This couple of septuagenarians runs an inn in Suttsu, located on the island of Hokkaido, in northern Japan. This village of 2,800 souls, 78% of which is made up of forests, is picturesque and is located between mountains and the sea.

It is here that a nuclear waste storage project has been taking shape since 2020. Suttsu and the neighboring village of Kamoenai (800 inhabitants) were the only ones to apply to the Radioactive Waste Management Corporation (Numo), created by the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry and the electricity companies, and were selected to receive, within 20 years, the 19,000 tons of radioactive waste piling up in the country’s power plants, particularly in Fukushima Dai-chi and Rokassho in Aomori, where storage capacity is saturated.

In Japan, between the villages of Suttsu and Kamoenai, which have applied for the radioactive waste burial project, is the Tomari nuclear power plant. In Japan, between the villages of Suttsu and Kamoenai, which have applied for the radioactive waste disposal project, is the Tomari nuclear power plant.

Although Suttsu officially submitted its application, the inhabitants feel that they were not consulted and accuse the municipal council of having made the decision alone. Miki Nobuka, 50 years old, says she learned that the project was approved while she was buying her bread. This mother has been campaigning ever since to “stop it for our children”.

More than 50% of the inhabitants against

According to Kazuyuki Tsuchiya’s calculations, “more than 50% of the inhabitants of Suttsu are against”. Not having had access to the details of the project, “the council makes heavy decisions in plenary sessions”. The residents feel betrayed and angry. “The mayor wants to take advantage of the subsidies to develop the city, but we don’t want it,” he says.

According to Kazuyuki Tsuchiya’s calculations, “more than 50 percent of the residents of Suttsu are against” the radioactive waste disposal project.

In the first phase of the project, which consists mainly of soil investigation, 15 million euros are paid to each of the two municipalities. Fifty-three million in the second phase, which is to be voted on by referendum. The city council can say stop at any time,” says a Numo spokesperson. A vote will validate the continuation of each phase.”

Lack of transparency

But “we want to have access to all the documents: it’s unacceptable,” says Kazuyuki Tsuchiya, who won his case in the Hakodate administrative court last March for lack of transparency on the part of local authorities. The court ruled that the city of Suttsu should publicly share all the minutes of the city council meeting during which the vote for the final storage project was held. The vote for the second phase, originally scheduled for November, has therefore been postponed to a later date.

When contacted, the mayor of Suttsu refused to answer our questions. The Kishida government has announced the restart of 17 of its reactors by 2023 and the probable construction of new ones in the future. The Prime Minister also declared that before each restart, the local population, who live near the said plants, would be consulted. A promise that makes the inhabitants of Suttsu smile bitterly.

Tons of Japanese nuclear waste may be destined for overseas disposal

April 17, 2022

TOKYO (Kyodo) — Japan’s nuclear power plants have over 57,000 tons of large equipment that have, or will in time, become radioactive industrial waste and may be destined to be disposed of overseas, a tally of electric power company data showed Saturday.

The scale of the would-be hazardous waste underscores the ongoing move within the government to reexamine a rule banning the exports of radioactive waste at a time when few municipalities are willing to accept such waste.

Creating an exception to the rule under the foreign exchange law would allow power companies to commission contractors overseas to dispose of certain types of large equipment on the condition they are recycled in the destination countries.

But critics say radioactive waste created in Japan should not be forced on other countries and that such waste should be recycled domestically by improving related disposal technology.

The tally showed nuclear power plants in the country had 57,230 tons of the large equipment, including those still in use, at the end of March.

The equipment in question comes in three types. Steam generators create steam used to generate electricity, while feedwater heaters heat the water that goes back into a reactor and casings are used to store or transport spent nuclear fuel.

For example, there are 37 used steam generators, weighing a total of 12,000 tons, according to the tally. Twenty-two generators, or 7,500 tons, remain at reactors to be decommissioned, while another 51 units, or 15,300 tons, are still in use.

The crippled Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant has 3,360 tons of spent nuclear fuel casings. But the industry ministry says it sees no scenario in which waste emerging from the plant’s decommissioning process would be disposed of overseas.

The tally did not include data on the Tokyo Electric Power Company Holdings Inc. plant. Tohoku Electric Power Co. declined to provide data.

Decommissioning of nuclear reactors is expected to speed up from the mid-2020s in Japan, with an attendant increase in radioactive waste. Already, 24 commercial reactors are due to be decommissioned.

Radioactive waste is expected to be buried underground, depending on its pollution levels. But few disposal sites have been picked, leaving the handling of large reactor equipment, in particular, in limbo.

A steam generator is a large cylindrical metal object that is 20 meters long and weighs 300 tons. Because of its size, it cannot be easily cut up, encased in drums and buried.

Kansai Electric Power Co. has 21 generators stored away on its premises. “We are concerned about having little room left on our premises (at power plants) going forward as it would impact decommissioning work,” a company source said.

“It is virtually impossible to dispose of the waste domestically. The regulatory reconsideration is a gleam of hope for the waste issue that is at a dead-end,” the source added, expressing hope for overseas disposal.

One company the Japanese side is talking with about possible waste export is EnergySolutions Inc., a U.S. nuclear service company and a major player in the reactor decommissioning business.

The Utah-based company has processed over 60,000 tons of waste produced in reactor decommissioning in and outside of the United States.

A company official expressed confidence that it can process not just the three types of large reactor equipment under consideration for export, but other waste, such as metals from the Fukushima Daiichi plant.

Tatsujiro Suzuki, a Nagasaki University professor, who served as an acting head of the government’s Atomic Energy Commission, is critical of the envisioned disposal of radioactive waste overseas.

“This is what you get when the state has failed to seriously discuss what to do with waste,” Suzuki said, warning that it is a slippery slope and could lead to an export of waste from the Fukushima nuclear disaster.

“It is sheer irresponsibility when looked at from the principle that disposal must be done in one’s own country.”

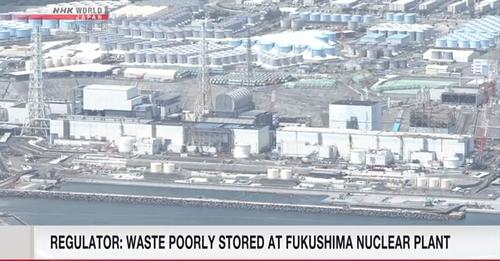

Regulators: Waste stored poorly at Fukushima plant

Sept. 18, 2021

Japanese nuclear regulators have urged the operator of the disabled Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant to improve the way it manages accumulating waste at the complex.

Most of the radioactive waste generated through decommissioning of the plant is being stored at designated outdoor depots.

But wreckage and other clutter that cannot be quickly transported there is instead being kept at interim sites for up to one year in principle.

The Nuclear Regulation Authority says the volume of waste at the interim sites reached 60,000 cubic meters in July, surging more than eight-fold from the figure in January of last year.

It also says the waste has been kept longer than one year in some sites, and not enough patrols are being conducted.

The plant’s operator, Tokyo Electric Power Company, says it could not send the waste to the outdoor depots while work was underway to rearrange containers there. It adds that the containers had to be inspected following leaks of radioactive substances.

The company says it will review the temporary storage arrangements and manage waste properly.

The total volume of radioactive waste at the plant reached about 480,000 cubic meters as of March of this year, 10 years after the triple nuclear meltdown accident.

In desperate search of disposal sites for its nuclear waste, Japan offers poisonous grants to two small villages

Masao Takimoto chez lui à Kamoenai, sur l’île d’Hokkaido au Japon, devant des affiches où l’on peut lire « Non aux déchets nucléaires ».

November 9, 2020

One morning in September, 87-year-old retiree Masao Takimoto was reading the newspaper in his house in Kamoenai when a news story captured his attention, ruined his day and changed the course of this quiet fishing village on the island of Hokkaido, in northern Japan : the mayor of the village of 822 had agreed to a preliminary study to host a disposal site for highly radioactive nuclear waste, for which the Japanese government would award 2 billion yen (€16 million, US$19 million) in subsidies.

Mr Takimoto didn’t waste a single minute. He wrote a letter of protest and delivered it by hand to the mayor’s house. Over the following days, he produced and distributed leaflets alerting others to the dangers of the nuclear disposal site and tried to gain access to the meetings that were being hastily held. His journey to activism resulted in tensions and anonymous threats. Ultimately he was unable to stop the mayor from signing on 9 October an application with the Nuclear Waste Management Organisation (NUMO), a quasi-governmental body charged with managing Japan’s radioactive waste.

Meanwhile, just 40 km away, another fishing village of 2,900 inhabitants quickly mobilised to prevent their mayor from volunteering for the same study. Suttsu, 40 per cent of whose inhabitants are over 65 years old, announced in August its interest in applying for the large subsidy to combat depopulation. Haruo Kataoka, 71, the town’s mayor since 2001, has been accused of ignoring civil society groups, national anti-nuclear organisations, fishers’ associations, leaders of neighbouring municipalities, the think tank CEMIPOS and even the governor of Hokkaido. The region, a major source of fishing and agricultural resources, has an ordinance opposing nuclear waste in its territory.

“We want to vote on the proposal. We’re worried about our fishing industry. If nuclear waste is stored here and there are problems in the future, we won’t be able to protect the environment or our jobs,” says Toshihiko Yoshino, a fishing entrepreneur in Suttsu. Yoshino processes and sells the local specialty, oysters, young sardines and anchovies. On 10 September, with a group of residents both young and old, he founded the organisation ‘No to Nuclear Waste for the Children of Suttsu.’ They collected signatures to request a referendum. On the eight day they launched a campaign to implement it, in collaboration with civil groups in the region. Their efforts were in vain : the mayor signed the application in Tokyo the following day. The previous morning, a Molotov cocktail exploded at the mayor’s house, an incident that left no one injured.

Someone broke the bicycle that Junko Kosaka, 71, was using to hand out leaflets against the nuclear disposal site. She has been a member of the opposition in the Suttsu council for nine years and laments the tension and discord between neighbours. “The village has no financial problems. There are fishing companies and profitable sales of fish. We receive a large budget from Japanese citizens who support rural areas through the Hometown Tax scheme.” She was surprised by the age of NUMO’s managers, all of whom are elderly, and believes that young people should decide their own future. “I would like the managers to reflect, to rethink nuclear energy. We are a country of disasters.”

Emptying villages and poor employment prospects

Japan is the world’s fourth largest producer of nuclear power after the United States, France and China. Distributed across the archipelago, 54 reactors generated 30 per cent of electricity until 2011. Despite having shut down the majority of reactors following the fatal accident of Fukushima, Japan’s commitment to nuclear energy remains firm, though not without controversy. Nine reactors are still in operation and 18 are waiting to be reactivated to generate 20 per cent of the country’s electricity in 2030.

Since 2002, the government has been looking for a location for a permanent geological repository, concrete structures at least 300 metres below ground that will store radioactive waste for millennia so as not to affect life and the environment. Desperate to solve a global and irreversible problem of the nuclear age, Japan is offering subsidies to encourage localities to host the repository. Small villages with declining populations and uncertain futures are attracted by the promise of money and jobs. The first phase will consist of two years of feasibility research. For the following phase, a four-year preliminary geological investigation, villages will receive an additional 7 billion. The final phase will consist of digging and the construction of the underground facility, a process that will last 14 years. But where is the waste ? “It cools off in overflowing pools while time runs out,” say many frustrated opponents of nuclear energy in Japan.

For decades Japan has been shipping tons of spent fuel to France and England for reprocessing, but the resulting radioactive waste must be returned to the country of origin for disposal by the IAEA. Japan only has a temporary repository (between 30 and 50 years – and half of that time is already up) in the village of Rokkasho, but 40,000 highly polluting cylinders are waiting for a permanent storage (the construction of which could take at least 20 years). The central government must also find storage for low-intensity waste occupying the equivalent of eight Olympic-size swimming pools. Every time a power plant operator uses gloves, a suit or tools, the earth fills with rubbish that contaminates for generations. France, Belgium, Sweden and Spain already have disposal sites for several centuries and Finland has just opened a permanent site in one of the oldest rock formations in Europe.

In 2007, the city of Toyo asked to enter the preliminary study but soon backed out after facing strong local opposition. In 2017, the central government released a map of potentially suitable sites. It ruled out sites near active volcanoes and fault lines, as well as areas with recent seismic activity. A wide area of Suttsu and a small portion of Kamoenai are seen to be favourable. Both locations are very close to the Tomari nuclear power plant, which is currently inactive.

The residents of Suttsu turned to experts for help. On 2 October, Hideyuki Ban, co-director of the Citizens’ Nuclear Information Centre came to the town with a renowned geologist to provide information to residents. According to the nuclear expert : “There is no space for the nuclear repository in Suttsu. We have to reclaim land from the sea and there hasn’t been enough research. Our country is not a geologically stable territory.” He says that 200 people attended the seminar, including the mayor “who must have already made the decision.” Is it safe ? “It is not safe, there could be leaks. Currently there is no appropriate technology in the world for handling radioactive waste. The only way to reduce it is to shut down the plants.” So what should be done with the waste ? “More research should be done and it should be buried using deep borehole disposal at more than 3,000 metres below the earth’s surface.”

A debated that is not promoted

Nobody in Kamoenai wants to talk to the press. By mid-morning, the boats have returned and the women are cleaning the salmon for sale. There are empty houses and closed businesses which have seen better days. In the main street, an imposing building is under construction : the new town hall, just opposite the old one. “I’m an employee of the town hall and I’m not authorised to respond,” says one young woman. “I’m not an expert, I can’t give an opinion,” says a young man. “I don’t want to talk, I could lose my job,” says a worried woman. “We have the power plant nearby and nothing bad has ever happened,” says another evasively. Takimoto is the only person willing to speak out without fear : “It’s an obscure and cowardly process, nothing is transparent. The political administration is stifling the voices of the people. It’s strange that the most important thing, safety, isn’t being mentioned. We have to think about future dangers.”

“The government claims that it will be safe for years to come, that’s their argument. But should we believe it ? The experts say the opposite. Just this year, on the 75th anniversary of the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, I was reading testimonies that made me cry. I have seen the effects of radiation on patients. I don’t want the children of Fukushima or of my village to suffer from it. We have to imagine a village without a nuclear power station or nuclear waste and that’s what I’m going to dedicate myself to,” he adds.

“I’ve been booed at local meetings, but there are people who support me in secret. Many of them pretend to be in favour but deep down they’re not. They don’t speak out for fear of losing their jobs, like the relatives of plant employees.” Takimoto refuses to give up. He has offered his experience in the health sector as a resource to help revitalise the town through projects such as medical tourism, but he has been unable to prevent the application from going through.

The Japanese government has welcomed the two locations (Kamoenai and Suttsu) and NUMO’s president expressed gratitude “for the courageous step”. The Minister of Industry said that they “will do their best to win the support of the people.” But the governor of Hokkaido has firmly stated that he will oppose the second phase. Those who oppose the disposal site fear that receiving the subsidies will make it difficult to back out due to government pressure. According to local journalists Chie Yamashita and Yui Takahashi of the Mainichi Shinbun : “Without going into whether or not applying is the right thing to do, there needs to be a debate about the management of radioactive waste and the process of selecting a location.” Everyone consulted for this article is calling for a national debate, which the government has not yet set in motion.

Some residents, like Takimoto, continue to protest : “No to nuclear waste. Life is more important than money.” On the poster, a baby dreams of a world and an ocean without pollution.

https://www.equaltimes.org/in-desperate-search-of-disposal#.X6mvJVBCeUl

Aomori wants reassurance that it won’t be final nuclear waste site

Aomori Gov. Shingo Mimura (left) and Chief Cabinet Secretary Katsunobu Kato (right) attend a meeting of a council for nuclear fuel cycle policy held at the Prime Minister’s Office Wednesday.

Oct 21, 2020

Aomori Prefecture on Wednesday urged the government to reconfirm its policy of not building in the prefecture a facility for the final disposal of high-level radioactive waste from nuclear power plants across the nation.

The request was made during a meeting of a council for discussions on issues related to the country’s nuclear fuel cycle policy between relevant Cabinet ministers and officials of the prefecture, where a spent nuclear fuel reprocessing facility is under construction. It was the first meeting of the council since November 2010.

At the day’s meeting, the Aomori side called on Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga’s Cabinet, launched last month, to maintain the promise not to make the prefecture a final disposal site, upheld by past administrations.

Participants in the meeting, held at the Prime Minister’s Office in Tokyo, included Chief Cabinet Secretary Katsunobu Kato and industry minister Hiroshi Kajiyama from the central government, and Aomori Gov. Shingo Mimura.

“It’s necessary for the state and the operator (of the reprocessing plant) to make the utmost efforts to promote, with support from Aomori, the nuclear fuel cycle policy, including the launch of the plant,” Kato said at the start of the meeting.

Mimura told reporters after the meeting that he asked the central government to abide by the promise and promote the nuclear fuel cycle policy, in which uranium and plutonium are extracted from spent fuel and reprocessed into fuel for use at nuclear power plants.

Mimura indicated that Kato showed the state’s understanding of his requests.

In July, the central government’s Nuclear Regulation Authority concluded that the basic design of the nuclear fuel reprocessing plant in the Aomori village of Rokkasho meets the country’s nuclear safety standards, which were crafted after the March 2011 accident at Tokyo Electric Power Company Holdings Inc.’s tsunami-stricken Fukushima No. 1 nuclear plant.

Japan Nuclear Fuel Ltd. aims to complete the plant in fiscal 2022. The NRA spent over six years screening the Rokkasho facility’s design.

Following the NRA’s conclusion, the Aomori side asked the state to hold a meeting of the nuclear fuel cycle policy council.

Aomori has agreed to accept spent nuclear fuel from nuclear plants across the country on the condition that a final disposal facility is not constructed in the prefecture.

The central government regards the nuclear fuel cycle as a pillar of its nuclear energy strategy.

Besides the reprocessing plant, a facility to make mixed oxide, or MOX, fuel from extracted uranium and plutonium is also under construction at the same site in Rokkasho.

https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2020/10/21/national/japan-aomori-nuclear-waste-disposal/

Mansion without a toilet: Towns in Japan seek to house, store nuclear waste out of necessity

Oct 12, 2020

Two remote towns in northern Japan struggling with rapidly graying and shrinking populations signed up Friday to possibly host a high-level radioactive waste storage site as a means of economic survival.

Japanese utilities have about 16,000 tons of highly radioactive spent fuel rods stored in cooling pools or other interim sites, and there is no final repository for them in Japan — a situation called “a mansion without a toilet.”

Japan is in a dire situation following the virtual failure of an ambitious nuclear fuel recycling plan, in which plutonium extracted from spent fuel was to be used in still-unbuilt fast breeder reactors. The problem of accumulating nuclear waste came to the fore after the 2011 Fukushima nuclear power plant disaster. Finding a community willing to host a radioactive dump site is difficult, even with a raft of financial enticements.

On Friday, Haruo Kataoka, the mayor of Suttsu town on the northwestern coast of Hokkaido, applied in Tokyo for preliminary government research on whether its land would be suitable for highly radioactive waste storage for thousands of years.

Later Friday in Kamoenai just north of Kamoenai, village chief Masayuki Takahashi announced his decision to also apply for an initial feasibility study.

Suttsu, with a population of 2,900, and Kamoenai, with about 800 people, have received annual government subsidies as hosts of the Tomari nuclear power plant. But they are struggling financially because of a declining fishing industry and their aging and shrinking populations.

The preliminary research is the first of three steps in selecting a permanent disposal site, with the whole process estimated to take about two decades. Municipalities can receive up to 2 billion yen ($19 million) in government subsidies for two years by participating in the first stage. Moving on to the next stage would bring in more subsidies.

“I have tried to tackle the problems of declining population, low birth rates and social welfare, but hardly made progress,” Takahashi told reporters. “I hope that accepting research (into the waste storage) can help the village’s development.”

It is unknown whether either place will qualify as a disposal site. Opposition from people across Hokkaido could also hinder the process. A gasoline bomb was thrown into the Suttsu mayor’s home early Thursday, possibly by an opponent of the plan, causing slight damage.

Hokkaido Gov. Naomichi Suzuki and local fisheries groups are opposed to hosting such a facility.

One mayor in southwestern Japan expressed interest in 2007, but faced massive opposition and the plan was spiked.

High-level radioactive waste must be stored in thick concrete structures at least 300 meters (yards) underground so it won’t affect humans and the environment.

A 2017 land survey map released by the government indicated parts of Suttsu and Kamoenai could be suitable for a final repository.

So far, Finland and Sweden are the only countries that have selected final disposal sites

Japan Struggles to Secure Radioactive Nuclear Waste Dump Sites

A small, aging town grapples with the financial lure of storing radioactive waste underground.

Japan’s worsening depopulation crisis is crippling the public finances of regional towns. Now one small town has made national headlines after expressing interest in storing radioactive nuclear waste underground in a last ditch effort to save itself from impending bankruptcy.

The small town of Suttsu in Hokkaido, the northernmost main island of Japan, has a population of just under 3,000 people. It’s the first local municipality to volunteer for the permanent storage site of highly radioactive nuclear waste and nuclear spent fuel. Suttsu Mayor Kataoka Haruo says the town has no more than 10 years left to find new sources of income after struggling with a slump in sales of seafood due to the global coronavirus pandemic.

Kataoka says there is an impending sense of crisis unless an urgent financial boost in the form of a government grant can be secured. He has called on local residents not to dismiss the idea of applying for the phase one “literature survey” without weighing the ways the grant could be spent — in contrast to the harsh reality of town funds running dry in 10 years’ time.

In Japan there are more than 2,500 containers of nuclear waste being stored in limbo without a permanent disposal site. Currently, the waste is stored temporarily in Aomori prefecture in northwest Japan at the Japan Nuclear Waste Storage Management Center. According to the Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry there are also approximately 19,000 tons of spent nuclear fuel stored at each nuclear power plant.

Nuclear waste projects immense heat and it needs to be cooled through exposure to air for between 30 to 50 years before it can be transferred and stored underground. However, it takes roughly 1,000 years to 100,000 years for radiation intensity to drop to safe levels.

The 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster left long-lasting trauma further exasperating Japan’s already vexed relationship with nuclear energy as a resource deficient nation. The aftermath of the disaster and the slow road to recovery prompted many people to object to nuclear waste storage not only on geographic grounds but also out of strong emotional opposition.

Hokkaido has built a global reputation for its high quality dairy, agricultural products, and seafood. Nuclear waste storage, and the negative publicity that would follow, could jeopardize those industries.

With the proposal, local residents in Sutsu have been placed in a difficult situation, weighing up the health of their children and future generations against the town’s financial prospects and viable funding opportunities.

In August, Kataoka said he would not apply for phase one without the understanding of the general public. Last week, Kataoka held a local briefing session aiming to deepen local understanding and consent. But after discussing the damage to the town’s reputation and the possible conflict with a previous ordinance against accepting nuclear waste set by a radioactive waste research facility created in Hokkaido in 2000, Kataoka indicated the application for phase one would likely be delayed.

In 2000 the government enacted the Final Disposal Law, which outlined criteria for electing a permanent storage site. A three-stage investigation process sets out excavation to be deeper than 300 meters below ground and in doing so a survey of volcanoes, active fault lines, and underground rock must be performed in addition to installing an underground survey facility. It’s estimated that steps one through to three will take approximately 20 years in total.

In 2017 the government released a scientific map of Japan, pinpointing towns with suitable geographic conditions to host final disposal sites. If the application and survey are approved successfully, towns are eligible for grants up to 2 billion yen (around $19 million at current exchange rates) from the central government and another 7 billion yen if stage two goes ahead. In 2002 The Nuclear Waste Management of Japan (NUMO) launched an open call for local municipalities to consider applying for an initial investigation stage without success. Three years after the release of the map, NUMO has attempted to garner public support by hosting over 100 local discussion meetings all over Japan. Suttsu was the first town to express interest in phase one out of 900 local municipalities.

The final nuclear waste site is expected to make room underground for 40,000 barrels requiring six to 10 square kilometers — the equivalent of 214 Tokyo Dome Stadiums — to a tune of 3.9 trillion yen.

The government is currently formulating a “nuclear fuel cycle policy,” which aims to reduce the amount of nuclear waste generated by encouraging the recycling and reuse of spent fuel. But one major criticism of Japan’s nuclear power policy is the lack of a comprehensive strategy. The two year period for a “literature survey” has been touted as an opportunity for Japan to seriously consider the cleanup of nuclear power.

Nuclear waste disposal is a matter of environmental concern

Aug 31, 2020

It has been reported that the town of Suttsu in Hokkaido is considering applying for a two-year “literature research” into the possibility of storing high-level radioactive nuclear waste. A maximum of ¥2 billion in subsidies will be granted by the central government.

“The future of the town is financially precarious,” said Haruo Kataoka, the mayor of Suttsu, in an interview.

But the money that is thought to revive the town cannot reverse what the nuclear waste is likely to cause.

It is, in my opinion, never a financial issue, but a matter of environmental concern.

What is in question here is high-level radioactive nuclear waste, which can be dangerous for at least 200,000 years and therefore must be handled with the utmost care. It is indeed a problem that any country with nuclear power plants needs to address, however thorny it is. Any indiscreet decision is deemed extremely irresponsible and profoundly unethical.

“Financially precarious,” I must stress, is by no means comparable to environmentally threatening. Besides, it is specifically stated in a Hokkaido ordinance that nuclear waste is hardly acceptable in the prefecture.

Before a final disposal site is selected, or even before an application for research is submitted, the scientific facts ought to be thoroughly understood and the residents properly informed.

The span of recorded history is merely 5,000 years, while 200,000 years is far beyond human experience and comprehension. We certainly cannot live to see what is going to become of the nuclear waste, but I believe that we do not want to leave the thorny problem unaddressed to haunt our future generations.

Jive Sun

Sapporo

No Japan prefectures positive about hosting nuclear waste site

Aug 14, 2020

Nearly half of Japan’s 47 prefectures said they are opposed to or held negative views about hosting a deep-underground disposal site for high-level radioactive nuclear waste, a Kyodo News survey showed Friday.

None expressed a favorable stance. The result signals further woes for the central government in its attempt to find a permanent geological disposal repository.

Little progress has been made since the process to find local governments willing to host one started in 2002, due mainly to opposition from local residents.

The survey was sent to all prefectures in July, with additional interviews conducted depending on their answers.

While 16 prefectures such as Fukushima, Kanagawa and Okinawa clearly opposed hosting a site, seven others including Hokkaido, Kyoto and Nagasaki also expressed negative views.

Most of the others did not make their positions clear.

Of the total 23 prefectures that opposed or showed negative views, seven host nuclear power plants.

“We are already undertaking a certain amount of social responsibility by hosting nuclear plants and providing energy,” Niigata Prefecture said in its response.

Fukui Prefecture said, “We are generating power. Nuclear waste disposal should be handled by others.”

Meanwhile, Hokkaido mentioned its existing ordinance to prevent nuclear waste from being brought into the northernmost main island, a view that contradicts the relatively positive stance held by one of its municipalities. The town of Suttsu said Thursday it is considering signing up for preliminary research into its land to gauge its suitability for hosting a disposal site.

On Friday, however, its mayor, Haruo Kataoka, said the town has been asked by the prefecture not to apply for the preliminary study.

Before Suttsu, the town of Toyo in Kochi Prefecture applied for the study in 2007, but it later withdrew the application following strong protests by local residents.

In the Kyodo News poll, the western prefecture expressed opposition to hosting a disposal site, saying it faces the need to take measures against a possible major earthquake in the region.

For permanent disposal, high-level radioactive waste, produced as a result of the process of extracting uranium and plutonium from spent fuel, must be stored more than 300 meters underground so that it cannot impact human lives or the environment.

Elsewhere in the world, Finland and Sweden are the only countries to have decided on final disposal sites.

Hokkaido town mayor eyes hosting nuclear waste site

This facility in Finland is the only one where construction has begun on a final storage site for nuclear waste.

This facility in Finland is the only one where construction has begun on a final storage site for nuclear waste.

August 14, 2020

The mayor of Suttsu in western Hokkaido is bracing for a backlash after stating that he wants his small town to be considered as a final destination for nuclear waste by the central government.

“When I think about the future of our town, where the population has been shrinking, there is a need for financial resources to promote industry,” said Haruo Kataoka, 71, in an interview with The Asahi Shimbun.

“I am prepared for whatever form of bashing I may encounter.”

Kataoka may be in for a long fight.

Selecting the site for the nation’s final storage of nuclear waste is a three-stage process that can take up to 20 years. At each stage, the central government provides any municipality that has applied with annual grants.

Kataoka said he was considering having Suttsu apply for the first stage in which past records about natural disasters and geological conditions for the area are examined.

This stage normally takes about two years, and the municipality can receive up to 1 billion yen ($9.3 million) a year or a maximum total of 2 billion yen.

The annual budget for the Suttsu town government is 5 billion yen. Its main industries are oyster farming and fishing for Atka mackerel.

As of the end of March, the town’s population was 2,893. The population has decreased by 30 percent over the past two decades.

To encourage municipalities to submit applications, the central government in July 2017 released a map of areas that were considered scientifically appropriate as a site for the final storage of nuclear waste.

Suttsu is the first municipality expressing an interest in applying since that map was released.

But it remains to be seen if local residents will go along with Kataoka’s idea. He will hold a meeting in September to explain his intention and a decision will be made thereafter whether to proceed with the application.

Kataoka has also expressed interest in moving toward the second stage of the selection process in which boring samples are taken from underground. This is part of the four-year process to determine if the area meets general conditions to enable the selection process to move to the third stage, in which a test facility will be constructed underground.

In the second stage, the municipality can receive up to 2 billion yen a year, or a maximum total of 7 billion yen.

A municipal government can decide at any time to withdraw from the selection process and the grants it has received until then do not have to be returned.

Because nuclear waste may take up to 100,000 years for radiation to reach safe levels, any final storage site would have to be constructed at least 300 meters underground.

Suttsu is classified at the highest of four levels of appropriateness, according to the map released by the central government. Its location facing the Sea of Japan makes Suttsu highly suitable for transporting nuclear waste to the storage site.

But in addition to possible local opposition, the town government will also have to take into consideration an ordinance approved by the Hokkaido prefectural government in 2000 regarding nuclear waste that said no such waste should be brought onto the main northern island.

In a statement released on Aug. 13, Hokkaido Governor Naomichi Suzuki said the ordinance, “is an expression of the desire not to allow a final storage site within Hokkaido, and I believe I have no alternative but to abide by the ordinance.”

Kataoka said that the first stage of the selection process was just a study that did not represent a violation of the ordinance.

But at each stage of the selection process, the views of the prefectural governor and municipality mayor are solicited and any opposition will stop the process from proceeding.

Meanwhile, Hiroshi Kajiyama, the industry minister who oversees the process for selecting a final storage site, told reporters on Aug. 13 that a number of municipalities in addition to Suttsu had expressed interest in obtaining information about the selection process.

While Kajiyama acknowledged his awareness of the Hokkaido ordinance, he added that applying for the first stage of the process did not mean the municipality would automatically move to the second stage.

The central government has had to resort to offering annual grants to encourage municipal governments to express an interest in becoming the site for the final storage of nuclear waste.

Commenting on the interest shown by Suttsu, one government source said, “It is a step forward, but if we think about the entire process as a marathon, the race has just started and the runners have not yet even left the stadium (to reach the road).”

Meanwhile, other municipalities that in the past showed some interest in becoming the final storage site have more often than not met with huge local opposition.

In 2007, the mayor of Toyo in Kochi Prefecture on the island of Shikoku expressed interest in applying without first consulting the town assembly. Local opposition was so strong that a candidate opposed to the idea defeated the incumbent in the next election and the application was withdrawn.

There have also been reports of other municipalities expressing an interest in applying, but no formal announcement has been made until now.

Japan now possesses about 19,000 tons of spent nuclear fuel, but no progress has been made in selecting a site for its final storage. Foreign nations have also experienced difficulties in securing a site for such storage.

Finland is the only nation where actual construction of such a facility has begun.

(This article was written by Yasuo Sakuma, Ichiro Matsuo, Rintaro Sakurai and Yu Kotsubo.)

-

Archives

- May 2024 (181)

- April 2024 (366)

- March 2024 (335)

- February 2024 (345)

- January 2024 (375)

- December 2023 (333)

- November 2023 (342)

- October 2023 (366)

- September 2023 (353)

- August 2023 (356)

- July 2023 (362)

- June 2023 (324)

-

Categories

- 1

- 1 NUCLEAR ISSUES

- business and costs

- climate change

- culture and arts

- ENERGY

- environment

- health

- history

- indigenous issues

- Legal

- marketing of nuclear

- media

- opposition to nuclear

- PERSONAL STORIES

- politics

- politics international

- Religion and ethics

- safety

- secrets,lies and civil liberties

- spinbuster

- technology

- Uranium

- wastes

- weapons and war

- Women

- 2 WORLD

- ACTION

- AFRICA

- Atrocities

- AUSTRALIA

- Christina's notes

- Christina's themes

- culture and arts

- Fuk 2022

- Fuk 2023

- Fukushima 2017

- Fukushima 2018

- fukushima 2019

- Fukushima 2020

- Fukushima 2021

- general

- global warming

- Humour (God we need it)

- Nuclear

- RARE EARTHS

- Reference

- resources – print

- Resources -audiovicual

- World

- World Nuclear

- YouTube

-

RSS

Entries RSS

Comments RSS