Farmers in Fukushima plant indigo to rebuild devastated town

March 2, 2021

MINAMISOMA, Japan — Because of radiation released by the Fukushima nuclear plant disaster a decade ago, farmers in nearby Minamisoma weren’t allowed to grow crops for two years.

After the restriction was lifted, two farmers, Kiyoko Mori and Yoshiko Ogura, found an unusual way to rebuild their lives and help their destroyed community. They planted indigo and soon began dying fabric with dye produced from the plants.

“Dyeing lets us forget the bad things” for a while, Mori said. “It’s a process of healing for us.”

The massive earthquake and tsunami on March 11, 2011, caused three of the reactors at the nuclear plant to melt and wrecked more than just the farmers’ livelihoods. The homes of many people in Minamisoma, about 20 kilometers (12 miles) from the plant, were destroyed by the tsunami. The disaster killed 636 town residents, and tens of thousands of others left to start new lives.

Mori and Ogura believed that indigo dyeing could help people in the area recover.

Mori said they were concerned at first about consuming locally grown food, but felt safe raising indigo because it wouldn’t be eaten. They checked the radiation level of the indigo leaves and found no dangerous amount.

Ten years after the disaster, Mori and Ogura are still engaged in indigo dyeing but have different missions.

To Mori, it has become a tool for building a strong community in a devastated town and for fighting unfounded rumors that products from Fukushima are still contaminated. She favors the typical indigo dyeing process that requires some chemical additives.

But Ogura has chosen to follow a traditional technique that uses fermentation instead as a way to send a message against dangers of modern technology highlighted by nuclear power.

Mori formed a group called Japan Blue which holds workshops that have taught indigo dyeing to more than 100 people each year. She hopes the project will help rebuild the dwindling town’s sense of community.

Despite a new magnitude 7.3 earthquake that recently hit the area, the group did not cancel its annual exhibition at a community center that served as an evacuation center 10 years ago.

“Every member came to the exhibition, saying they can clean up the debris in their houses later,” Mori said.

Ogura, who is not a member of the group, feels that a natural process is important because the nuclear accident showed that relying on advanced technology for efficiency while ignoring its negative aspects can lead to bad consequences.

“I really suffered during the nuclear accident,” Ogura said. “We escaped frantically in the confusion. I felt I was doing something similar again” by using chemicals.

“We seek too much in the way of many varieties of beautiful colors created with the use of chemicals. We once thought our lives were enriched by it, but I started feeling that wasn’t the case,” she said. “I want people to know what the real natural color looks like.”

Organic indigo dyes take more time and closer attention. Ogura first ferments chopped indigo leaves with water for a month and then mixes the result with lye which is formed on the surface of a mixture of hot water and ashes. It has to be kept at about 20 degrees C (68 degrees F) and stirred three times a day.

Part of the beauty of the process, Ogura says, is that it’s hard to predict what color will be produced.

With the support of city officials, Ogura started making silk face masks dyed with organic indigo.

She used to run an organic restaurant where she served her own vegetables before the disaster, but now runs a guesthouse with her husband in which visitors can try organic indigo dyeing.

Just 700 meters (2,300 feet) from Ogura’s house, countless black bags filled with weakly contaminated debris and soil are piled along the roadside. They have been there since after the disaster, according to Ogura’s husband, Ryuichi. Other piles are scattered around the town.

“The government says it’s not harmful to leave them there. But if they really think it’s not harmful, they should take them to Tokyo and keep them near them,” he said.

The radiation waste stored in the town is scheduled to be moved to a medium-term storage facility by March next year, a town official said.

https://www.startribune.com/farmers-in-fukushima-plant-indigo-to-rebuild-devastated-town/600029579/

In Rural Fukushima, ‘The Border Between Monkeys And Humans Has Blurred’

Shuichi Kanno, 79, walks in front of his home at dusk. Kanno has been dealing with hordes of macaque monkeys in his neighborhood in Japan. They frequently wake him up as they climb over his roof in the early morning hours.

September 10, 2020

Shuichi Kanno rips tape off the top of a large cardboard box at his house in the mountains in Fukushima prefecture in Japan. He opens the box and rustles around to pull out pack after pack of long, thin Roman candle fireworks. The words “Animal Exterminating Firework” are written in Japanese on the side of each canister.

Kanno has been battling hordes of macaque monkeys that have encroached upon his neighborhood in a rural area of Minamisoma. These fireworks are his main deterrent — not to cause the monkeys any physical harm, but to scare them away with a loud bang. That is, until they regain their confidence and come back a few days later, which they do like clockwork, Kanno says.

Kanno stacks fireworks on his coffee table to distribute to neighbors. The fireworks make a loud noise meant to scare, not injure, the monkeys.

“In the early morning while I’m sleeping, just when I’m about to wake up, I hear the noise,” the 79-year-old says in Japanese as he stacks the fireworks on his living room table. “The sound of the monkeys running around on the roof, getting into the gardens, eating all my food. I have to fight them.”

Hundreds of thousands of people evacuated this area nine years ago, fleeing plumes of radioactive material after three reactors exploded at the Daiichi nuclear power plant, one of the most serious nuclear disasters in history. Whole towns and neighborhoods like Kanno’s were left empty of human life for years — and, much like Chernobyl, nature started to reclaim the space. Plants poke through sidewalks and buildings, while wild boar, raccoons and foxes roam the streets. But in recent years, many evacuation orders have lifted and people have started to return, meaning humans and animals are having to figure out new ways to coexist — or not.

A macaque monkey in a tree in Fukushima prefecture. After the 2011 nuclear disaster, towns and neighborhoods in Fukushima were left devoid of humans for years, and nature started to reclaim the space.

“The monkeys never used to come here, but after the disaster, the border between monkeys and humans has blurred,” Kanno explains. “The houses were empty, but the gardens were still growing — plums, pears, chestnuts, persimmons. It was a wonderland for monkeys, an all-you-can-eat buffet. And they remembered that.”

His neighborhood is on the very edge of the evacuation area, relatively far from Daiichi. People stayed away for only a few years, but by the time they came back, the monkeys had become comfortable. And, Kanno points out, half the houses are still empty and only older people came back. They just don’t have the numbers they need to win the battle against the monkeys without backup.

From left: Shuichi Kanno, Shigeko Hoshino, Hiroyuki Shima and Hachiro Endo are neighbors who moved back to Fukushima after the nuclear disaster and who get regular visits from monkeys that eat fruits and vegetables from their gardens.

That is where the fireworks come in, subsidized by the local government after residents complained. The governments here have provided several different kinds of tools, such as wild boar traps and electric fences for farmers, to help communities with animal problems.

Yuriko Kanno, 75, Shuichi’s wife, comes into the living room, looks at the pile of fireworks and laughs. “I’ve been worried that this village is going to become like that movie, the monkey planet one,” she says, referring to Planet of the Apes. “I’ve seen it — it could happen!”

She walks away giggling. Shuichi Kanno is laughing too. The monkeys are annoying, yes, but they’re also a source of entertainment for the aging residents, he concedes.

Yuriko Kanno, 75, is amused by the battle between her husband and the monkeys.

“Look, I think they’re cute. I would absolutely never hurt them,” he says. “None of this is their fault. It’s nuclear power’s fault. It’s the fault of humans.”

Shuichi Kanno is a leader in the neighborhood, and he’s in charge of distributing the fireworks to any of his neighbors who want them. The neighbors all have to sign an agreement saying they understand the dangers and — most importantly, he says — that they will not hurt any animals.

He loads the fireworks into the trunk of his car and drives down forest roads from house to house, dropping off packs of fireworks at every stop. As he drives, he points to all the natural beauty in the area. The nuclear disaster didn’t just change his relationship with monkeys, he says.

“I loved hiking, and foraging for wild vegetables, finding wild mushrooms. But now it’s so dangerous,” Kanno explains, referring to the high levels of radioactive cesium still present in the dense forests here. “We can’t have a relationship with nature anymore. It’s gone.”

Kanno drives his truck down a main road in his neighborhood, chasing monkeys that he saw scampering around his house not long ago.

He pulls up to the house of Hachiro Endo, 77, whose family has been in the area for generations. The home has a beautiful garden in front and long strands of drying persimmons hanging in the garage.

Endo is delighted by the delivery. He has gone through his entire stockpile protecting his garden. “I’m alert all the time,” Endo sighs. “The monkeys, they’ve taken over my life.”

He says he remembers a time when he was little and his grandfather tried to lure the monkeys down from the mountains into the village, hoping to boost tourism to the area by becoming a monkey town. He was never successful — the macaques were too afraid of humans to come down and stay.

“If only he could see it now,” he says with a laugh.

A troop of monkeys scampers across a road in Fukushima prefecture.

A few days later, Kanno is out on monkey patrol. He has just seen a troop of monkeys running from his house out into the neighborhood. He’s wearing knee-high rubber boots, a bright orange jacket and a baseball cap while clutching a firework in one hand and the steering wheel of his pickup truck in the other.

He drives slowly, leaning forward to scan the hills as he goes. And then suddenly, he slams on his brakes.

“There they are!” he shouts, pointing behind a shed. Dozens of monkeys are jumping toward the forest, scrambling up trees and crawling up the hillside.

He jumps out of the truck and pulls the firework from underneath his jacket, loading it onto a kind of stick so he can hold it far away. He lights the fuse and smiles, pointing it toward the hill.

Kanno grins after shooting off a firework to scare off monkeys that were roaming through the neighborhood.

Three loud booms echo through the trees. The monkeys scatter. Kanno bursts into a grin, giggling. Then he runs to every house nearby, making sure his neighbors know that he just saved their gardens from almost certain devastation.

“They won’t be back tomorrow!” Kanno calls, waving the spent firework, giddy with excitement. “I won today!”

But even as he says that he loads a fresh firework and tucks it into his coat. The monkeys will be back, and the battle will continue.

Beach in Fukushima Prefecture reopens for first time since 2011 disasters

Former mayor expresses anger at Tepco in trial over Fukushima crisis

Film on one man’s agony due to 2011 disaster wins key award

Tepco ordered to pay $30,000 each to 318 people of the Minamisoma’s Odaka District class action suit

Comparison study of calculated beta- and gamma-ray doses after the Fukushima accident in Minamisoma: skin dose estimated to be 164 mSv over 3 years

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION

(a) Mirror condition calculation, (b) top view and (c) side view of the calculation geometry.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Air dose rates of (a) beta rays and (b) gamma rays over time.

Comparison of the calculated beta rays (chain line), gamma rays (dotted line), beta + gamma rays (solid line), dose averaged over sample depth (dashed histogram), and data measured by Stepanenko et al. (open circles).

The calculated tissue dose at a brick depth of 50 μm was assumed to be a skin dose, and would be similar to a 70-μm tissue dose. The skin dose was estimated to be 164 mSv for 3 years at the sampling location.

CONCLUSION

To confirm the cause of the dose enhancement near the surface of a brick sample taken from Odaka, Minami-Soma City, Japan, a Monte Carlo calculation was performed using PHITS code and the calculated results were compared with measurements. The calculated results agreed well with previously published measured data. The dose enhancement at the brick surface in the measured data was explained by the beta-ray contribution, and the gentle slope in the dose profile deeper in the brick was due to the gamma-ray contribution. The calculated result estimated the skin dose to be 164 mGy (164mSv) over 3 years at the sampling location.

Source: https://academic.oup.com/jrr/advance-article/doi/10.1093/jrr/rrx099/4827065

New study says Minami-soma as safe as Western Japan cities – do they really expect us to believe this?

On September 5, 2017, Minami-soma city made a statement on the city’s radiation levels compared to 3 cities in West Japan, which has been reported in several newspapers. It’s important to comment on this study because the statement is intended to persuade the population to return to live there.

We are publishing comments on the articles below after having discussed with M. Ozawa of the citizen’s measurement group named the “Fukuichi Area Environmental Radiation Monitoring Project“. For English speaking readers, please refer to the article of Asahi Shimbun in English. For our arguments we refer to other articles published in other newspapers – Fukushima Minyu and Fukushima Minpo – which are only in Japanese.

Here are the locations of Minami-soma and the 3 other cities.

Here is the article of the Asahi Shimbun

Fukushima city shows radiation level is same as in west Japan

By SHINTARO EGAWA/ Staff Writer

September 5, 2017 at 18:10 JST

MINAMI-SOMA, Fukushima Prefecture–Radiation readings here on the Pacific coast north of the crippled Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant are almost identical to those of sample cities on the other side of Japan.

The Minami-Soma government initiated the survey and hopes the results of the dosimeter readings, released Sept. 4, will encourage more evacuees to return to their home areas after they fled in the aftermath of the 2011 nuclear disaster.

A total of 100 portable dosimeters were handed out to 25 city employees from each of four cities–Minami-Soma, Tajimi in Gifu Prefecture, Fukuyama in Hiroshima Prefecture and Nanto in Toyama Prefecture. They were asked to take them wherever they went from May 29 through June 11.

The staff members were evenly dispersed with their homes in all corners of the cities they represented.

In addition, only those living in wooden houses were selected as different materials, concrete walls, for example, are more effective in blocking radiation.

In July 2016, evacuation orders for most parts of Minami-Soma were lifted, but not many residents have so far returned.

The city’s committee for health measures against radiation, which is made up of medical experts, analyzed the data.

The median value of the external radiation dosage of the 25 staff of Minami-Soma was 0.80 millisieverts per annum, while the average value was 0.82 mSv per annum, according to Masaharu Tsubokura, the head of the committee and a physician at Minami-Soma general hospital.

No significant difference was found in the three western cities.

Both figures were adjusted to include the natural radiation dose, and are below the 1-mSv per annum mark set by the national government as the acceptable amount of long-term additional radiation dosage, which is apart from natural radiation and medical radiation dosages.

The radiation doses in all cities were at levels that would not cause any health problems, according to Tsubokura.

“Making comparisons with other municipalities is important,” Tsubokura said. “I am intending to leave the survey results as an academic paper.”

Our comments

1) The difference of life style between city employees and local agricultural population

As we see in the article, portable dosimeters were handed out to city employees. They spend most of their day time in an office protected by concrete walls which are efficient for blocking radiation as stated in the article. However, in Minami-soma, most of the population spends more time outside, very often working in the fields. Their life style is different and therefore the external radiation dose cannot be similar to those of city employees. The result of the comparison between the external radiation dose of city employees cannot be used as an argument to say that it is safe for the local population to live in Minami-soma.

2) In the article of Fukushima Minyu, it is stated that in Minami-soma the radiation dose has a wider range than in the other three cities. This means that there are hotspots, which leads to higher risks of internal irradiation.

3) The radiation dose expressed in terms of Sieverts is relevant for radioprotection when the source of radiation is fixed and identified. This is the case for most of the nuclear workers. However, in the case of Fukushima after the nuclear accident where the whole environment is radio-contaminated and the radioactive substances are dispersed widely everywhere, it is not a relevant reference for radioprotection. It is important in this case to measure surface contamination density, especially of soil.

4) 6 years and 6 months since the accident, cesium has sunk in the soil. It is thought to be between 6 and 10 cm from the surface. This means the top layer of soil from 0 to 5 cm is blocking the radiation, reducing the measures of the effective dose. However, this does not mean that the population is protected from internal irradiation, since cesium can be re-scattered by many means, by digging or by flooding, for example.

5) The reliability of individual portable dosimeters has already been raised many times. This device is not adequate to capture the full 360° exposure in radio-contaminated environments as described in point 3 above.

6) In the article, it is stated that background radiation is included in the compared values, but it does not mention the actual background radiation measurements in the 4 cities.

The Table of Fukushima Minyu

Radiation dose of the 4 cities

Values include the background radiation dose

Values include the background radiation dose

To summarize, the sample study group does not represent the overall population. The study doesn’t include the risks of internal radiation, for which the measurement of contaminated soil is indispensible. The dosimeters are not adequate to measure the full load of radio-contaminated environments. So, the research method is not adequate to draw the conclusion to say that it is safe for the population to return to live in Minami-soma.

The Minamisoma Whistleblowers, Fukushima

A few days ago Pierre Fetet learned of a map which immediately called his attention.

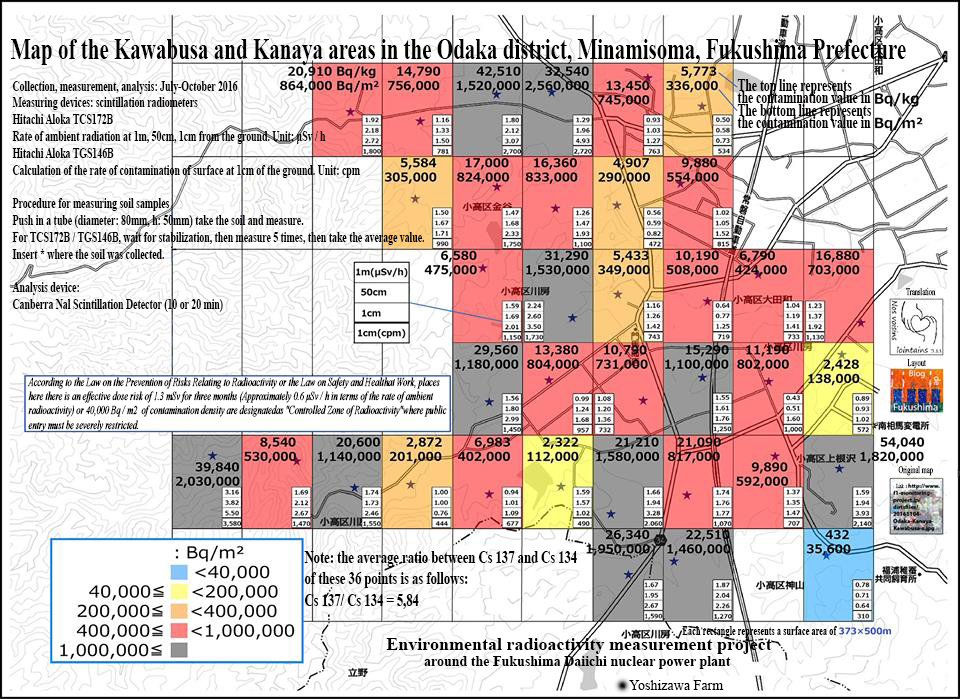

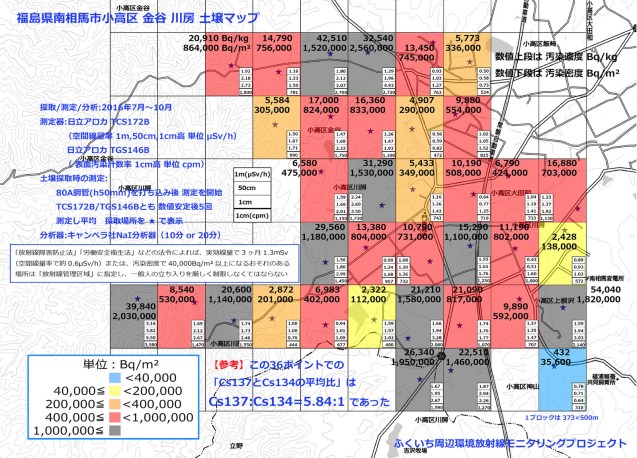

That map displays at the same time precise and unsettling measurements. Not knowing Japanese, Pierre Fetet asked Kurumi Sugita, the president of Nos voisins lointains 3.11 association, to translate for him the text. She immediately accepted and explained to him what it was:

“The project to measure environmental radioactivity around the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant (“Fukuichi Area Environmental Radiation Monitoring Project“) is conducted by a team of relatively old volunteers (who are less radiosensitive than youth) to perform radioactivity measurements with a tight mesh size of 75 x 100 m for radioactivity in air and 375 x 500 m for soil contamination. Measurements of ambient radioactivity and soil radioactivity are carried out mainly in the city of Minamisōma and its surroundings. They try to make detailed measurements so as to show the inhabitants the real conditions of their lives, and also to accumulate data for the analysis of long-term health and environmental damages.”

Thanks to the Kurumi Sugita’s translation and with the agreement of Mr. Ozawa, author of the document, Pierre Fetet was able to make a French version of this map, which I translated into english here below:

Map of Mr. Ozawa’s team,“Fukuichi Area Environmental Radiation Monitoring Project” (translation first by Kurumi Sugita, then by Hervé Courtois)

In the context of the normalization of contaminated areas into habitable areas, the evacuation order of the Odaka district of the city of Minamisōma was lifted on 12 July 2016, except the area bordering Namie (Hamlet of Ohatake where a single household lives) classified as a “difficult return” area.

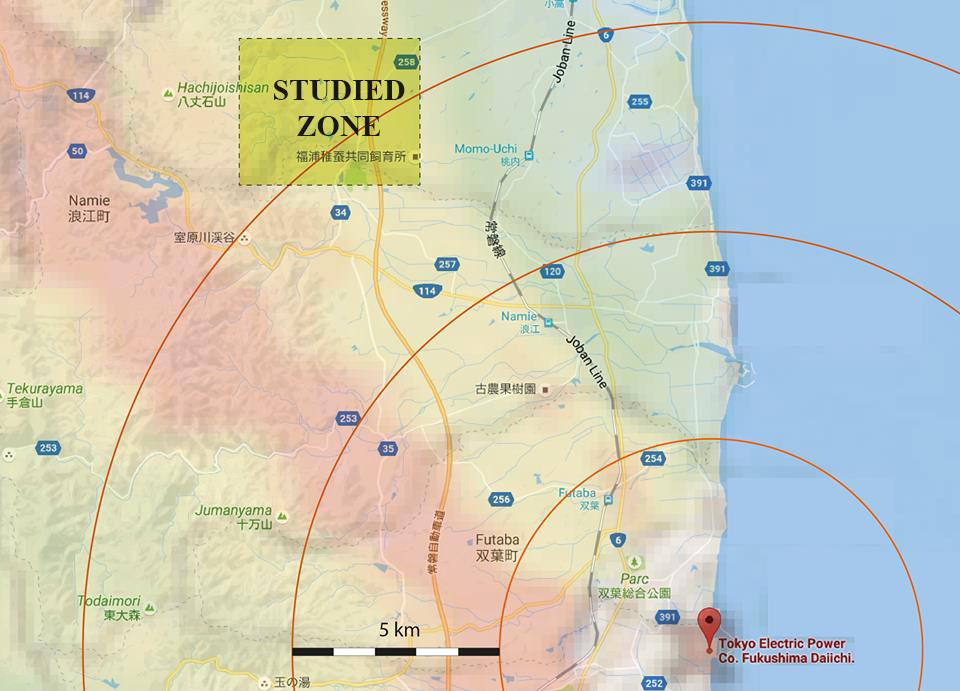

Situation of the study area

The contamination map examines the Kanaya and Kawabusa areas of the Odaka district, about fifteen kilometers from the former Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant. Mr. Ozawa, the engineer who launched this investigation, has chosen the precision of the measurements, that is to say laboratory scintillation radiometers are used to measure radioactivity: Hitachi Aloka TCS172B, Hitachi Aloka TGS146B and Canberra NaI Scintillation Detector.

The originality of this map is due as much to the quality of its realization as to the abundance of its informations: it can be read, for each of the 36 samples taken, measurements in Bq / m², in Bq / kg, in μSv / h at three different soil heights (1 m, 50 cm, 1 cm) And in cpm (counts per minute) at the height of 1 cm. For those who know a little about radioactivity, these informations are very valuable informations. Usually, measurements are given in either unit, but never simultaneously with 4 units. Official organizations should learn this way of working.

The measures revealed by the map are very disturbing. They show that the earth has a level of contamination that would make it a radioactive waste in any uncontaminated country. As Mr. Ozawa writes, these lands should be considered a “controlled zone”, that is to say a secure space, as in nuclear power plants, where the doses received must be constantly checked. In fact, it is worse than inside of a nuclear power plant because in Japan the inhabitants evacuated since five and a half years are now asked to return home, whereas it is known that they will be irradiated (Up to 20 mSv / year) and contaminated (by inhalation and ingestion).

This citizen research is remarkable in more ways than one:

- It is independent of any organization. There is no lobby to alter or play down this or that measure. These are just raw data, taken by honest people, in search of truth.

- It respects a scientific protocol, explained on the map. There will always be people to criticize this or that aspect of the process, But this one is rigorous and objective.

- It takes measurements 1 m from the ground but also 1 cm from the ground. This approach is more logical because until now men are walking on the ground no? The contamination maps of Japan often show measurements at 1 m from the ground, Which does not reflect reality and seems to be done to minimize the facts. Indeed, the measurement is often twice as high at 1 cm from the ground as at 1 m.

- It acts as a revealing map. Mr. Ozawa and his team are whistleblowers. Their maps say: Watch out ! Laws contradict each other in Japan. What the government claims, namely that a dose of 20 mSv / year will not produce any health effect, is not necessarily the truth. If you come back, you are going to be irradiated and contaminated.

France is preparing for the same forfeiture, namely that ‘it is transposing into national law the provisions of Directive 2013/59 / Euratom: the French authorities retained the upper limit of the interval: 100 mSv for the emergency phase and 20 mSv for the following 12 months (And for the following years there is no guarantee that this reference level will not be renewed). These values apply to all, including infants, children and pregnant women! ” (source Criirad)

The Japanese government is asking residents to return home and abolishing compensation for evacuees. The Olympics are coming, Fukushima must be perceived as “normal” so that the athletes and supporters of the whole world won’t be afraid, even if it means sacrificing the health of the local population. It is therefore necessary to make known the map of Mr. Ozawa so that future advertising campaigns do not stifle the reality of the facts.

Pierre Fetet

Data on measurements at Minamisōma

http://www.f1-monitoring-project.jp/open_deta.html

Website of the measuring team: “Fukuichi Area Environmental Radiation Monitoring Project“

http://www.f1-monitoring-project.jp/index.html

Address of the original map (HD)

http://www.f1-monitoring-project.jp/dirtsfiles/20161104-Odaka-Kanaya-Kawabusa-s.jpg

Source : Article of Pierre Fetet

http://www.fukushima-blog.com/2016/11/alerte-a-minamisoma.html

(Translation Hervé Courtois)

Home at last, but little joy as evacuee picks up pieces of her life

3 km’s up the coast. 1.8 miles to Minami-Soma from fuk. …. “The Japanese government steered displaced people toward their return by repeating that an annual exposure of up to 20 millisieverts poses little health risk,”

Tomoko Kobayashi, right, prepares with a volunteer worker for the reopening of her Futabaya ryokan in the Odaka district of Minami-Soma, Fukushima Prefecture, on July 11.

MINAMI-SOMA, Fukushima Prefecture–It was no ordinary homecoming for Tomoko Kobayashi, after an enforced absence of more than five years due to the 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster.

She says she is “in no mood for celebration” given the daunting task facing her: having to start from scratch at the traditional ryokan inn that has been in the family for nearly 70 years.

The community that Kobayashi had called home was overrun with rats, wild boar and palm civets, and she struggled to protect the family business from that nightmare.

Kobayashi’s journey home to start afresh took her via Ukraine, which she visited in 2013 to learn how victims of the world’s worst nuclear accident–the Chernobyl disaster in 1986–were coping after all those years.

Kobayashi, 63, was shocked by the different approach authorities there had taken compared with that of Japan.

She said Ukraine takes a more cautious approach toward radiation risks.

Kobayashi returned to Minami-Soma’s Odaka district on July 12 after the central government lifted a ban for 11,000 or so evacuees from the district, which is within a 20-kilometer radius of the crippled Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant.

Her initial concern is living with low-level radiation.

She also worries for her future and whether she can get the business up and running. With her husband, Takenori, 67, Kobayashi has reopened Futabaya ryokan. The inn that she took over from her mother 10 years ago has 15 guest rooms and is located in front of JR Odaka Station, which is 16 km from the plant.

Another of her concerns centers on whether her return home to reopen the inn could play into the hands of the authorities.

“The central government is eager to wind up the program that compensates the victims,” she said, alluding to a sense that evacuees are being encouraged to return so that financial redress can end.

On the plus side, the radiation level in her neighborhood has dropped to below 0.2 microsievert per hour. Although it is three times the level before the triple meltdown in March 2011, the figure is significantly lower than in the immediate aftermath.

Since the disaster, Kobayashi has closely monitored the radioactivity of food, drinking water and soil by working with a local citizens group. In one instance, radioactivity registered more than 10,000 becquerels per kilogram when she measured the levels of the dust and dirt sucked up in a vacuum cleaner at her home.

Returning home means she still faces the risk of exposure to long-term, low radiation. How this could affect her health is not understood by scientists.

Odaka was previously designated a “zone in preparation for the lifting of the evacuation order,” where an annual radiation dose is estimated at 20 millisieverts or below.

Extensive decontamination work over the past three years paved the way for the evacuees’ return.

Despite the lifting of the ban, only 10 to 20 percent of the residents from Odaka and other parts of Minami-Soma are expected to go back.

Evacuees are reluctant because of the potential hazard of the long-term, low radiation exposure and the new living and social networks built during the five years they were away.

They are also wary of the risks of moving back in the vicinity of the nuclear complex where the unprecedented scale of work to decommission the damaged reactors is under way amid a host of challenges, including an accumulated buildup of highly radioactive water.

Before the nuclear accident, Kobayashi had a staff of five that washed and starched the linen. It was a hallmark of her ryokan’s hospitality. With only one staffer coming back, however, Kobayashi has to forgo the starched sheets.

At one point, more than 60,000 of the city’s 72,000 residents evacuated, including those who left voluntarily.

After she moved into temporary housing in Minami-Soma in 2012, Kobayashi occasionally visited the inn to clean up. The dark waters of the tsunami, spawned by the magnitude-9.0 tremor on March 11, 2011, almost reached the front door of her ryokan, even though it is situated 3 km from the coast.

Her neighborhood, which was blessed with a wide array of edible wild plants, mushrooms and freshwater fish, was transformed into a “gray ghost town.” The landscape became increasingly bleaker as gardens of homes were occupied by piles of black plastic bales containing radioactive waste from the cleanup operation.

Kobayashi had many sleepless nights. She wondered whether she could ever pick up the threads of the existence she led before the catastrophe.

Her turning point came in September 2013 when she joined a tour to the region in Ukraine devastated by the Chernobyl accident.

“I was curious to know how victims of a nuclear accident considered more serious than Fukushima’s are faring nowadays,” Kobayashi said.

Kobayashi also wanted to convey her gratitude to those affected by the Chernobyl explosion in Zhytomyr province for sending 150 dosimeters to Minami-Soma. The devices proved to be invaluable at a time when the city badly needed them.

When her tour group visited Zhytomyr, the residents there shared their experiences and answered questions sincerely.

What struck Kobayashi during the trip was the disparity between Ukraine’s local government and Japanese authorities in their handling of radiation risks and programs made available to help the victims.

In Ukraine, authorities are more hands-on.

“No Trespassing” and other warning signs were put up in communities, although their doses of radiation were lower than that in Odaka. Ukraine authorities issued a warning on the basis of radioactive contamination in the ground as it could lead to internal radiation exposure of residents through the spread of radioactive dust.

She also learned that a large number of people in Zhytomyr have developed health problems, not just cancer, but also a wide variety of diseases.

But they are guaranteed by law the right to receive treatment or to take refuge.

That is in sharp contrast with the Japanese government briefings with evacuees, which barely touched on the long-term, low radiation risks.

Kobayashi is outraged by this.

“The Japanese government steered displaced people toward their return by repeating that an annual exposure of up to 20 millisieverts poses little health risk,” she said.

Kobayashi said she would have been less suspicious of the intention of Japanese officials if they had candidly admitted that they didn’t know about the possible effects on health.

She is also angered about the way authorities treated evacuees in light of the July 12 lifting of the ban.

Evacuees from Minami-Soma’s Kawabusa district, a mountainous area that fell in the “residence restriction zone,” were also allowed to return. The zone is defined as one registering an estimated annual dose of between 20 to 50 millisieverts.

Although a dose in Kawabusa was confirmed to have dropped to less than 20 millisieverts, the clearance came as a surprise to many locals since it ran counter to the government’s previous policy of designating such an area first a zone in preparation for the lifting.

Kawabusa is home to about 300 people, including many children.

Despite a drop in radiation readings in her community, Kobayashi said she cannot ask her grandchildren, who are 8 and 2, to come visit her and her husband yet.

But she is determined to make an effort for rebuilding.

“I don’t know how many more years it will take to bring back the happy sounds of children to our community, but I am determined to do what I can do now,” Kobayashi said.

http://www.asahi.com/ajw/articles/AJ201608050001.html

Evacuation order lifted in Minami-Soma after 5 years, affecting 10,000 people

For the first time in five years, a train begins service on the 9.4-kilometer stretch between Odaka and Haranomachi stations in Minami-Soma, Fukushima Prefecture, on East Japan Railway Co.’s Joban Line at 7:33 a.m. on July 12.

Evacuation order lifted in Minami-Soma after 5 years

MINAMI-SOMA, Fukushima Prefecture–In good news for residents, an evacuation order for the southern part of the city here was lifted on July 12 for the first time since the massive earthquake and tsunami crippled the Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant five years ago.

However, due to lingering fears of radiation contamination, less than 20 percent of the populace are set to return to their homes.

The central government allowed residents back into the southern region of the city after midnight on July 11. It marks the sixth time that evacuation orders have been lifted for locales in Fukushima Prefecture, following such municipalities as Naraha and Katsurao.

The latest lifting in Minami-Soma affects a total of 10,807 residents in 3,487 households in all parts of the Odaka district and parts of the Haramachi district, making it the largest number of people to be let back into their homes since evacuation zones were established following the 2011 nuclear disaster.

Two residents living in a household in an area designated a “difficult-to-return” zone in the southern part of the city are still not allowed back home.

However, only about 2,000 residents signed up to stay overnight at their homes in the area ahead of the lifting of the evacuation order.

That is likely because many still fear the effects of radiation from the destroyed power plant, which straddles the towns of Futaba and Okuma to the south of Minami-Soma. In addition, five years was more than enough time for residents who evacuated elsewhere to settle down.

With at least some of the residents returning home, East Japan Railway Co. resumed service on the 9.4-kilometer stretch between Odaka and Haranomachi stations on the Joban Line for the first time in more than five years on the morning of July 12. The first train of the morning entered Odaka Station carrying 170 or so people on two cars as traditional flags used in the Soma Nomaoi (Soma wild horse chase) festival on the platform greeted passengers.

The central government is pushing to lift evacuation orders on all areas of the prefecture excluding difficult-to-return zones by March 2017.

http://www.asahi.com/ajw/articles/AJ201607120054.html

Japan lifts evacuation orders in Fukushima affecting 10,000 people

FUKUSHIMA, Japan (Kyodo) — The government on Tuesday further scaled down areas in Fukushima Prefecture subject to evacuation orders since the March 2011 nuclear disaster at the Fukushima Daiichi complex, enabling the return of more than 10,000 residents to the city of Minamisoma.

Following the move, the city will become mostly habitable except for one area containing one house. But many residents seem uneager to return, having begun new lives elsewhere.

The government is in the process of gradually lifting evacuation orders issued to areas within a 20-kilometer radius of the plant of Tokyo Electric Power Company Holdings Inc. and in certain areas beyond the zone amid ongoing radiation cleanup efforts.

Eight municipalities in Fukushima Prefecture have areas defined as evacuation zones, which are divided into three categories based on their radiation levels. The most seriously contaminated area is called a zone “where it is expected that the residents have difficulties in returning for a long time.”

In Minamisoma, the government lifted evacuation orders for areas except for the difficult-to-return zone. As of July 1, the areas had a registered population of 10,807, or 3,487 households.

To encourage evacuees to return, the central government and the city reopened hospital facilities, built makeshift commercial facilities and prepared other infrastructure.

Radiation cleanup activities have finished in residential areas, but will continue for roads and farmland until next March.

The government hopes to lift the remaining evacuation orders affecting areas other than the difficult-to-return zones by next March, officials said.

http://mainichi.jp/english/articles/20160712/p2g/00m/0dm/031000c

Japan lifts evacuation order for city near nuclear plant

Minamisoma is one of the most contaminated places in Fukushima. Decontamination is never permanent. Some places already have been decontaminated up to 5 times already, but the contamination always coming back gradually to the pre-decontamination levels thanks to the ruisseling rain and the wind bringing it from the forested hills where it has accumulated. Fukushima prefecture is 80% forested hills/mountains, all heavily contaminated.

The Japanese Government insists on perpetuating the decontamination lie, pushing the people to return to live in the previously evacuated areas, hammering in the media that low-radiation exposure is not harmful to health. Economic priorities prevailing above people lives.

Quoting Bo Jacobs: “This is entirely about removing legally obligated compensation. When you are forced to evacuate, the government is liable for the costs. When the government says that the radiation in your community is acceptable, then there is no more legal obligation to compensate you for living someplace that is safe. “

Tokyo: The Japanese government on Friday lifted an evacuation order for the entire city of Minamisoma, located near the disabled nuclear plant in Fukushima.

The decision, which is awaiting approval from the local council, will allow the return of 12,000 people to the municipalities included in the restricted area around the plant due to the nuclear disaster in 2011.

Minamisoma, with a population of 46,000, is located north of Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant, and the southern and western part of the city is still under the evacuation order, affecting around 11,700 people.

The government has decided to lift the restriction after completing the decontamination work in the residential and surrounding areas, a government spokesperson told state broadcaster NHK.

From next month onwards, Japan intends to allow evacuees to return to the Katsurao and Kawauchi villages too, which means that around 1,480 and 1,040 people will be able to return to their homes respectively.

The last municipality where the evacuation order was completely lifted was Naraha in September 2015, although the inhabitants have returned in small batches due to fear of persisting radiation, a shattered local economy and scarce availability of services.

Around 74,200 citizens throughout the Fukushima prefecture remain evacuated as a result of the earthquake and tsunami of March 11, 2011, out of which only around 4,500 have returned to the areas where the evacuation order has been lifted, according to the local government in February.

http://www.newsx.com/world/28364-japan-lifts-evacuation-order-for-city-near-nuclear-plant

-

Archives

- February 2026 (181)

- January 2026 (308)

- December 2025 (358)

- November 2025 (359)

- October 2025 (376)

- September 2025 (258)

- August 2025 (319)

- July 2025 (230)

- June 2025 (348)

- May 2025 (261)

- April 2025 (305)

- March 2025 (319)

-

Categories

- 1

- 1 NUCLEAR ISSUES

- business and costs

- climate change

- culture and arts

- ENERGY

- environment

- health

- history

- indigenous issues

- Legal

- marketing of nuclear

- media

- opposition to nuclear

- PERSONAL STORIES

- politics

- politics international

- Religion and ethics

- safety

- secrets,lies and civil liberties

- spinbuster

- technology

- Uranium

- wastes

- weapons and war

- Women

- 2 WORLD

- ACTION

- AFRICA

- Atrocities

- AUSTRALIA

- Christina's notes

- Christina's themes

- culture and arts

- Events

- Fuk 2022

- Fuk 2023

- Fukushima 2017

- Fukushima 2018

- fukushima 2019

- Fukushima 2020

- Fukushima 2021

- general

- global warming

- Humour (God we need it)

- Nuclear

- RARE EARTHS

- Reference

- resources – print

- Resources -audiovicual

- Weekly Newsletter

- World

- World Nuclear

- YouTube

-

RSS

Entries RSS

Comments RSS