Fukushima, Our ongoing accident.

Dec 19, 2022

What happens to the damaged reactors? The territories evacuated by 160 000 people? What are the new conditions for their return to the contaminated area since the lifting of the governmental aid procedures? Are lessons still being learned by our national operator for its own nuclear plants? We must not forget that a disaster is still unfolding in Japan and that EDF was supposed to upgrade its fleet on the basis of this feedback, which has still not been finalized.

Almost twelve years after the Fukushima disaster, Japan is still in the process of dismantling and ‘decontaminating’ the nuclear power plant, probably for the next thirty to forty years as well. In the very short term, the challenges are posed by the management of contaminated water.

- All the contaminated water will be evacuated into the sea, by dilution over decades

- Each intervention in the accident reactors brings out new elements

- This has an impact on the schedule and the efficiency of the means used

- At the same time, the Japanese government’s objective is to rehabilitate the contaminated areas at any cost

- None of the French reactors is up to date with its safety level according to the post-Fukushima measures promulgated

- Japan will resume its nuclear policy, time having done its work on memories

The great water cycle

Although Japanese politicians claim that they have finally mastered the monster, the colossal task of cleaning up the site is still far from being completed to allow for the ultimate dismantling, with the length of time competing with the endless financing.

After so many years of effort, from decontamination to the management of radioactive materials and maneuvers within the dismantled plant, the actions on site require more and more exceptional means, exclusive procedures, and unprecedented engineering feats (such as robotic probes), while the nuclear fuel inside continues to be cooled permanently by water (not without generating, to repeat, millions of liters of radioactive water).

But the hardest part is yet to come: containing the corium, an estimated 880 tons of molten radioactive waste created during this meltdown of the reactor cores, and managing the thousands of fuel rods. So much so that the complete cleanup and dismantling of the plant could take a generation or more for a total estimated cost of more than 200 billion dollars (according to an assessment published by the German insurer Munich Re, Japan is 150 billion euros), a low range since other estimates raise the bill between 470 and 660 billion dollars, which is not in contradiction with the costs of an accident projected by the IRSN in France.

The removal of this corium will remain the most essential unresolved issue for a long time. Without it, the contamination of this area will continue. In February 2022, the operator Tepco (Tokyo Electric Power Company Holdings Inc.) tried again to approach the molten fuel in the containment of a reactor after a few more or less unsuccessful attempts, the radioactivity of 2 sieverts/hour being the end of everything, including electronic robots. This withdrawal seems quite hypothetical, even the Chernobyl reactor has never been removed and remains contained in a sarcophagus.

(source: Fukushima blog and Japan’s Nuclear Safety Authority NRA)

Until that distant prospect arrives, the 1.37 million tons of water will have filled the maximum storage capacity. This water was used to cool the molten fuel in the reactor and then mixed with rainwater and groundwater. The treatment via an Advanced Liquid Processing System (ALPS) is touted as efficient, but does not remove tritium. Relative performance: Tepco has been repeatedly criticized for concealing and belatedly disclosing problems with filters designed to prevent particles from escaping into the air from the contaminated water treatment system: 24 of the 25 filters attached to the water treatment equipment were found to be damaged in 2021, an already known defect that resulted in no investigation of the cause of the problem and no preventive measures after the filters were replaced.

The management of this type of liquid waste is a problem shared by the Americans. On site, experts say that the tanks would present flooding and radiation hazards and would hamper the plant’s decontamination efforts. So much so that nuclear scientists, including members of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) and the Japanese Nuclear Regulatory Authority, have recommended controlled release of the water into the sea as the only scientifically and financially realistic option.

In the end, contaminated water would have to be released into the sea through an underwater tunnel about a kilometer offshore, after diluting it to bring the concentration of tritium well below the percentage allowed by regulation (the concentration would be below the maximum limit of tritium recommended by the World Health Organization for drinking water). Scientists say that the effects of long-term, low-dose exposure to tritium on the environment and humans are still unknown, but that tritium would affect humans more when consumed in fish. The health impact will therefore be monitored, which the government already assures us it is anticipating by analyzing 90,000 samples of treated water each year.

Assessment studies on the potential impact that the release of stored contaminated water into the ocean could have therefore seem insufficient. For tritium, in the form of tritiated water or bound to organic matter, in addition to its diverse behavior according to these configurations, is only part of the problem. Some data show great variability in the concentrations of contaminants between the thousand reservoirs, as well as differences in their relative quantities: some reservoirs that are poor in tritium are rich in strontium 90 and vice versa, suggesting a high variability in the concentrations of other radionuclides and a dilution rate that is not so constant. All the ignorance currently resides on the still unknown interactions of the long-lived radioactive isotopes contained in the contaminated water with the marine biology. It is in order to remove all questions that a complete and independent evaluation of the sixty or so radioisotopes is required by many organizations.

As it stands, with the support of the IAEA so that dilution meets expectations, depending on currents, flows …, the release of contaminated materials would take at least forty years. Opponents of such releases persist in proposing an alternative solution of storage in earthquake-resistant tanks in and around the Fukushima facility. For them, “given the 12.3-year half-life of tritium for radioactive decay, in 40 to 60 years, more than 90% of the tritium will have disappeared and the risks will be considerably reduced,” reducing the direct nuisance that could affect the marine environment and even the food chain.

Modelling of marine movements could lead the waste to Korea, then to China, and finally to the Federated States of Micronesia and Palau. As such, each of the impacted countries could bring an action against Japan before the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea to demand an injunction or provisional measures under international law.

Faced with these unresolved health issues, China, South Korea, Taiwan, local fishing communities continue to oppose this management plan, but the work is far from being completed and the problem of storage remains. Just like the ice wall built into the floor of the power plant, the release of contaminated water requires huge new works: the underwater pipe starts at about 16 meters underground and is drilled at a rate of five to six meters per day.

Time is of the essence. The tanks should reach their maximum capacity by the fall of 2023 (the volume of radioactive water is growing at a rate of about 130 to 140 tons per day). But above all, it is necessary to act quickly because the area is likely to suffer another earthquake, a fear noted by all stakeholders. With the major concern of managing the uranium fuel rods stored in the reactors, the risks that radioactivity will be less contained increase with the years.In France, releases to the sea are not as much of a problem: the La Hague waste reprocessing site in France releases more than 11,000 terabecquerels per year, whereas here we are talking about 22 terabecquerels that would be released each year, which is much less than most of the power plants in the world. But we will come back to this atypical French case…

Giant Mikado

The operator Tepco has successfully removed more than 1500 fuel bundles from the reactor No. 4 of the plant since late 2014, but the hundreds still in place in the other three units must undergo the same type of sensitive operation. To do this, again and again, undertake in detail the clearing of rubble, the installation of shields, the dismantling of the roofs of buildings and the installation of platforms and special equipment to remove the rods… And ultimately decide where all the fuel and other solid radioactive debris will have to be stored or disposed of in the long term. A challenge.

The fuel is the biggest obstacle to dismantling. The solution could lie, according to some engineers, in the construction of a huge water-filled concrete tank around one of the damaged reactors and to carry out the dismantling work in an underwater manner. Objectives and benefits? To prevent radiation from proliferating in the environment and exposing workers (water is a radiation insulator, we use this technique in our cooling pools in France) and to maximize the space to operate the heavy dismantling equipment being made. An immersion solution made illusory for the moment: the steel structure enveloping the building before being filled with water is not feasible as long as radiation levels are so high in the reactor building, preventing access by human teams. In short, all this requires a multitude of refinements, the complexity of the reactors adding to the situations made difficult by the disaster.

Experience, which is exceptional in this field, is in any case lacking. What would guarantee the resistance of the concrete of the tanks over such long periods of time, under such hydraulic pressures? The stability of the soils supporting such structures? How can the concrete be made the least vulnerable possible to future earthquakes? How to replace them in the future?

All these difficulties begin to explain largely the delays of 30 to 40 to dismantle. The reactors are indeed severely damaged. And lethal radiation levels equivalent to melted nuclear fuel have been detected near one of the reactor covers, beyond simulations and well above previously assumed levels. Each of the reactors consists of three 150-ton covers, 12 meters in diameter and 60 centimeters thick: the radiation of 1.2 sieverts per hour is prohibitive, especially in this highly technical context. There is also no doubt that other hotspots will be revealed as investigations are carried out at the respective sites. The Nuclear Damage Compensation and Decommissioning Facilitation Corporation (NDF), created in 2014, has the very objective of trying to formulate strategic and technical plans in order to proceed with the dismantling of said reactors. Given the physical and radiological conditions, the technical and logistical high-wire act.

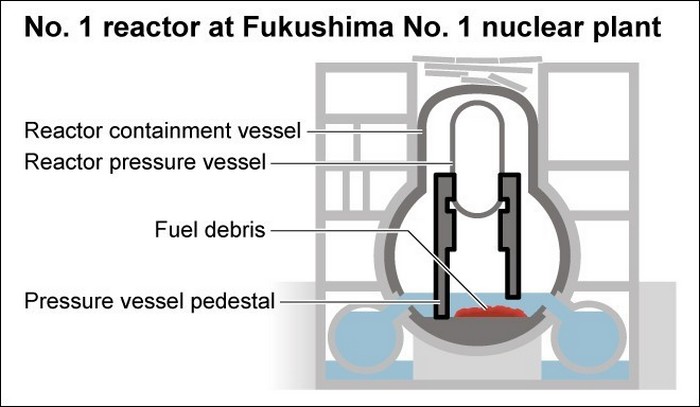

Also, each plan is revised as information is discovered, as investigations are conducted when they are operable. For example, the reinforcing bars of the pedestal, which are normally covered with concrete, are exposed inside Reactor No. 1. The concrete support foundation of a reactor whose core has melted has deteriorated so badly that rebar is now exposed.

The cylindrical base, whose wall is 1.2 meters thick, is 6 meters in diameter. It supports the 440-ton reactor pressure vessel. The reinforcing rods normally covered with concrete are now bare and the upper parts are covered with sediment that could be nuclear fuel debris. The concrete probably melted under the high temperature of the debris. The strength of the pedestal is a major concern, as any defect could prove critical in terms of earthquake resistance.

Nothing is simple. The management of human material appears less complex.

Bringing back to life, whatever it takes

In the mountains of eastern Fukushima Prefecture, one of the main traditional shiitake mushroom industries is now almost always shut down. The reason? Radioactive caesium exceeding the government’s maximum of 50 becquerels per kilogram, largely absorbed by the trees during their growth. More than ten years after the nuclear disaster, tests have revealed caesium levels between 100 and 540 becquerels per kilogram. While cesium C134 has a radioactive half-life of about two years and has almost disappeared by now, the half-life of cesium C137 is about 30 years and thus retains 30% of its radioactivity 50 years after the disaster, and 10% after a century.

As more than two thirds of Fukushima prefecture is covered by forests, nothing seems favorable in the short term to get rid of all or part of the deposited radioactivity, as forests are not part of the areas eligible for ‘decontamination’, unlike residential areas and their immediate surroundings.

On the side of the contaminated residential and agricultural areas, ‘decontamination’ measures have been undertaken. But soil erosion and the transfer of contaminants into waterways, frequent due to typhoons and other intense rain events, are causing the radioactive elements to return, moving them incessantly. Scientists are trying to track radioactive substances to better anticipate geographical fluctuations in doses, but nothing is simple: the phenomena of redistribution of the initial contamination deposits from the mountains to the inhabited low-lying areas are eternal.

The Ministry of the Environment is considering the reuse of decontaminated soils (official threshold of 8,000 becquerels per kilogram), with tests to be conducted. For now, a law requires the final disposal of contaminated soil outside Fukushima Prefecture by 2045, which represents about 14 million cubic meters (excluding areas where radiation levels remain high). This reuse would reduce the total volume before legal disposal.

More generally, Japan has for some years now opted for the strategy of holding radiological contamination as zero and/or harmless. This is illustrated by the representative example of the financial compensation given to farmers, designed so that the difference between pre- and post-accident sales is paid to them as compensation for “image damage”, verbatim.

Finally, in the midst of these piles of scrap metal and debris, it is necessary to make what can be made invisible. Concerning radioactive waste for example, it must be stored in time. On the west coast of the island of Hokkaidō, the villages of Suttsu and Kamoenai have been selected for a burial project. Stainless steel containers would be stored in a vitrified state. But consultation with the residents has not yet been carried out. This is not insignificant, because no less than 19,000 tons of waste are accumulating in the accidental, saturated power plants, and must find a place to rest for hundreds of years to come.

In this sparsely populated and isolated rural area, as in other designated sites, to help with acceptance, 15 million euros are being paid to each of the two municipalities to start the studies from 2020. 53 million are planned for the second phase, and much more in the final stages. This burial solution seems inevitable for Japan, as the waste cannot remain at the level of the surface power plants and is subject at all times to the earthquakes that are bound to occur over such long periods (strong earthquakes have struck off the prefecture in 2021 and 2022). The degrees of dangerousness thus allow the government to impose a default choice, for lack of anything better.

On December 6, 2022, the Director General of the IRSN met with the President of Fukushima University and with a manager of the Institute of Environmental Radioactivity (IER). What was the objective? To show the willingness of both parties to continue ongoing projects on the effects of radioactive contamination on biodiversity and environmental resilience.

But France will not have waited for the health results of a disaster to learn and commit itself to take into account any improvement likely to improve the nuclear safety of its reactors. No ?

Experience feedback

After a few reactor restarts that marked a major change in its nuclear energy policy (ten nuclear reactors from six plants out of a total of fifty-four were restarted by June 2022), the Japanese government is nonetheless planning to build new generation nuclear power plants to support its carbon emission reduction targets. (A memorandum of understanding was signed by the Japan Atomic Energy Agency, Mitsubishi Heavy Industries and Mitsubishi FBR Systems with the American start-up TerraPower to share data for the Natrium fast neutron reactor project; the American company NuScale Power presented its modular reactor technology). But above all, the government is considering extending the maximum service life of existing nuclear reactors beyond 60 years. Following the disaster, Japan had introduced stricter safety standards limiting the operation of nuclear reactors to 40 years, but there is now talk of modernizing the reactors with safety features presented as “the strictest in the world”, necessarily, to meet safety expectations. Their program is worthy of a major refurbishment (GK).

But in France, where are we with our supplementary safety assessments?

The steps taken after the Fukushima disaster to reassess the safety of French nuclear facilities were designed to integrate this feedback in ten years. More than ten years after the start of this process of carrying out complementary safety assessments (CSA), this integration remains limited and the program has been largely delayed in its implementation.

Apparently, ten years to learn all the lessons of this unthinkable accident was not enough. Fear of the probable occurrence of the impossible was not the best motivation to protect the French nuclear fleet from this type of catastrophic scenario, based solely on these new standards. Concerning in detail the reality of the 23 measures identified to be implemented (reinforcement of resistance to earthquake and flooding, automatic shutdown in the event of an earthquake, ultimate water top-up for the reactor and cooling pool, detection of corium in the reactor vessel, etc.), the observation is even distressing: not a single reactor in operation is completely up to standard.

According to NegaWatt’s calculations, at the current rate of progress and assuming that funding and skills are never lacking, it would take until 2040 for the post-Fukushima standards to be finally respected in all French reactors. And even then, some of the measures reported as being in place are not the most efficient and functional (we will come back to the Diesels d’ultime secours, the DUS of such a sensitive model).

Even for the ASN, the reception of the public in the context of post-accident management could appear more important than the effectiveness of the implementation of the measures urgently imposed.

Then, let us complete by confirming that France and Japan have a great and long common history which does not stop in nuclear matters. Among this history, let us recall that Japan lacks facilities to treat the waste from its own nuclear reactors and sends most of it abroad, especially to France. The previous transport of highly radioactive Mox (a mixture of highly toxic plutonium oxide and reprocessed uranium oxide) to Japan dates back to September 2021, not without risk even for the British company specialized in this field, a subsidiary of Orano. The final request for approval for the completion of the Rokkasho reprocessing plant, an important partnership and technology transfer project, is expected in December 2022, although the last shipments to Japan suffered from defective products from Orano’s Melox plant, a frequent occurrence because of a lack of good technical homogenization of the products.

No one is immortal

In the meantime, the ex-managers of the nuclear power plant have been sentenced to pay 95 billion euros for having caused the disaster of the entire eastern region of Japan. They were found guilty, above all, of not having sufficiently taken into account the risk of a tsunami at the Fukushima-Daiichi site, despite studies showing that waves of up to 15 meters could hit the reactor cores. Precisely the scenario that took place.

Worse, Tepco will be able to regret for a long time to have made plan the cliff which, naturally high of 35 meters, formed a natural dam against the ocean and the relatively frequent tsunamis in this seismic zone. This action was validated by the Japanese nuclear safety authorities, no less culpable, on the basis of the work of seismologists and according to economic considerations that once again prevailed (among other things, it was a question of minimizing the costs of cooling the reactors, which would have been operated with seawater pumps).

The world’s fourth largest public utility, familiar with scandals in the sector for half a century, Tepco must take charge of all the work of nuclear dismantling and treatment of contaminated water. With confidence. The final total estimates are constantly being revised upwards, from 11,000 billion to 21,500 billion yen, future budgets that are borrowed from financial institutions, among others, with the commitments to be repaid via the future revenues of the electricity companies. A whole financial package that will rely on which final payer?

Because Tepco’s financial situation and technical difficulties are deteriorating to such an extent that such forty-year timetable projections remain very hypothetical, and the intervention of the State as a last resort is becoming more and more obvious. For example, the Japanese government has stated that the repayment of more than $68 billion in government funding (interest-free loans, currently financed by government bonds) for cleanup and compensation for the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant disaster, owed by Tepco, has been delayed. Tepco’s mandatory repayments have been reduced to $270 million per year from the previous $470 million per year. It is as much to say that the envisaged repayment periods are as spread out as the Japanese debt is abysmal.

Despite this chaotic long-term management, the Japanese government has stated that it is considering the construction of the next generation of nuclear power plants, given the international energy supply environment and Japan’s dependence on imported natural resources. Once the shock is over, business and realpolitik resume.

On a human scale, only radioactivity is immortal.

Marie Curie’s Belongings Will Be Radioactive For Another 1,500 Years

By BARBARA TASCH, BUSINESS INSIDER, https://www.sciencealert.com/these-personal-effects-of-marie-curie-will-be-radioactive-for-another-1-500-years?fbclid=IwAR2mz5r9iMmKfNoIYm1ddsmsoLUqMZn7a84pCdZYKp5aYi1TWup0Tl0vkN4 21 Aug 2015

Marie Curie, known as the ‘mother of modern physics’, died from aplastic anaemia, a rare condition linked to high levels of exposure to her famed discoveries, the radioactive elements polonium and radium.

Curie, the first and only woman to win a Nobel Prize in two different fields (physics and chemistry), furthered the research of French physicist Henri Becquerel, who in 1896 discovered that the element uranium emits rays.

Alongside her French physicist husband, Pierre Curie, the brilliant scientific pair discovered a new radioactive element in 1898. The duo named the element polonium, after Poland, Marie’s native country.

Still, after more than 100 years, much of Curie’s personal effects including her clothes, furniture, cookbooks, and laboratory notes are still radioactive, author Bill Bryson writes in his book, A Short History of Nearly Everything.

Regarded as national and scientific treasures, Curie’s laboratory notebooks are stored in lead-lined boxes at France’s Bibliotheque National in Paris. Wellcome Library

While the library grants access to visitors to view Curie’s manuscripts, all guests are expected to sign a liability waiver and wear protective gear as the items are contaminated with radium 226, which has a half life of about 1,600 years, according to Christian Science Monitor.

Her body is also radioactive and was therefore placed in a coffin lined with nearly an inch of lead.

The Curie’s are buried in France’s Panthéon, a mausoleum in Paris which contains the remains of distinguished French citizens – like philosophers Rousseau and Voltaire.

Hot water — radiation in drinking water

Tighter controls called for as radiation contaminates US drinking water

Hot water — Beyond Nuclear International

Radioactive contamination is creeping into drinking water around the U.S.

https://beyondnuclearinternational.org/2023/01/01/hot-water/ By Lynne Peeples, Ensia 1 Jan 2023

When Jeni Knack moved to Simi Valley, California, in 2018, she had no idea that her family’s new home was within 5 miles of a former nuclear and rocket testing laboratory, perched atop a plateau and rife with contamination. Radioactive cesium-137, strontium-90, plutonium-239 and tritium, along with a mix of other toxic chemicals and heavy metals, are known to have been released at the industrial site through various spills, leaks, the use of open-air burn pits and a partial nuclear meltdown.

Once Knack learned about the Santa Susana Field Laboratory and the unusual number of childhood cancer cases in the surrounding community, she couldn’t ignore it. Her family now only drinks water from a 5-gallon (19-liter) jug delivered by Sparkletts water service. In August of 2021, she began sending her then 6-year-old daughter to kindergarten with two bottles of the water and instructions to not refill them at school, which is connected to the same Golden State Water Company that serves her home.

A federal report in 2007 acknowledged that two wells sourced by the water company were at risk of contamination from the site. “The EPA has said we’re at risk,” says Knack. And Golden State, she says, has at times used “possibly a very hefty portion of that well water.” To date, radioactivity above the natural level has not been detected in Golden State’s water.

Concerns across the country

All water contains some level of radiation; the amount and type can vary significantly. Production of nuclear weapons and energy from fissionable material is one potential source. Mining for uranium is another. Radioactive elements can be introduced into water via medical treatments, including radioactive iodine used to treat thyroid disorders. And it can be unearthed during oil and gas drilling, or any industrial activities that involve cracking into bedrock where radioactive elements naturally exist. What’s more, because of their natural presence, these elements can occasionally seep into aquifers even without being provoked.

The nonprofit Environmental Working Group (EWG, a partner in this reporting project) estimates that drinking water for more than 170 million Americans in all 50 states “contains radioactive elements at levels that may increase the risk of cancer.” In their analysis of public water system data collected between 2010 and 2015, EWG focused on six radioactive contaminants, including radium, radon and uranium. They found that California has more residents affected by radiation in their drinking water than anywhere else in the U.S. Yet the state is far from alone. About 80% of Texans are served by water utilities reporting detectable levels of radium. And concerns have echoed across the country — from abandoned uranium mines on Navajo Nation lands, to lingering nuclear waste from the Manhattan Project in Missouri, to contaminants leaching from phosphate mines in Florida.

While ingesting radioactive elements through drinking contaminated water is not the only route of human exposure, it is a major risk pathway, says Daniel Hirsch, a retired University of California, Santa Cruz, professor who has studied the Santa Susana Field Laboratory contamination. “One thing you don’t want to do is to mix radioactivity with water. It’s an easy mechanism to get it inside people,” he says. “When you drink water, you think you excrete it. But the body is made to extract things from what you ingest.”

Strontium-90, for example, is among elements that mimic calcium. So the body is apt to concentrate the contaminant in bones, raising the risk of leukemia. Pregnant women and young kids are especially vulnerable because greater amounts of radiation are deposited in rapidly growing tissue and bones. “This is why pregnant women are never x-rayed,” says Catherine Thomasson, an independent environmental policy consultant based in Portland, Oregon. Cesium can deposit in the pancreas, heart and other tissues, she notes. There, it may continue to emit radioactivity over time, causing disease and damage.

Scientists believe that no amount of radiation is safe. At high levels, the radiation produced by radioactive elements can trigger birth defects, impair development and cause cancer in almost any part of the body. And early life exposure means a long period of time for damage to develop.

Health advocates express concern that the government is not doing enough to protect the public from these and other risks associated with exposure to radioactive contamination in drinking water. The legal limits set by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) for several types of radioactive elements in community water systems have not been updated since 1976. Further, many elements are regulated as a group rather than individually, such as radium-226 plus radium-228. And water system operators, if they are required to monitor for radioactive elements, only need to do so infrequently — say, every six or nine years for certain contaminants.

Meanwhile, private wells generally remain unregulated with regard to the elements, which is particularly concerning because some nuclear power plants are located in rural areas where people depend on private wells. More than one out of every 10 Americans use private wells or tiny water systems that serve fewer than 15 residences.

The Santa Susana Field Laboratory was rural when it was first put to use about 70 years ago. Today, more than 700,000 people live within 10 miles (16 kilometers). Recent wildfires have exacerbated these residents’ concerns. The 2018 Woolsey fire started on the property and burned 80% of its 2,850 acres (1,153 hectares). Over the following three months, the levels of chemical and radioactive contamination running off the site exceeded state safety standards 57 times.

Hirsch highlights several potential avenues for drinking water contamination related to nuclear weapons or energy development. Wind can send contamination off site and deposit it into the soil, for example. Gravity can carry contaminants downhill. And rains can carry contamination via streams and rivers to infiltrate groundwater aquifers. While vegetation absorbs radioactive and chemical contaminants from the soil in which it grows, those pollutants are readily released into the environment during a fire.

While no tests have detected concerning levels of radioactivity in Golden State’s water, advocates and scientists argue that testing for radioactive elements remains inconsistent and incomplete across the country. Federal and state regulations do not require monitoring for all potential radioactive contaminants associated with the known industrial activity on the site. For some of the regulated contaminants, water companies need only test once every several years.

“This is not an isolated matter,” says Hirsch. “We’re sloppy with radioactive materials.”

“We need stricter regulations”

In 2018, around the same time that fires stirred up radioactive elements in and around the Santa Susana Field Laboratory, drinking water concerns arose just outside of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Guy Kruppa, superintendent of the Belle Vernon Municipal Authority, had been noticing major die-offs of the bacteria in his sewage treatment plant. The bugs are critical for breaking down contaminants in the sewage before it is discharged into the Monongahela River. About 1 mile (1.6 kilometers) downstream is a drinking water plant.

Kruppa and his colleagues eventually linked the low bacteria numbers to leachate they accepted from the Westmoreland landfill. The landfill had begun taking waste from nearby fracking sites — material that included bacteria-killing salts and radioactive elements such as radium.

The Belle Vernon Municipal Authority subsequently got a court order to force the landfill to stop sending its leachate — the liquid stuff that flows off a landfill after it rains. “We sealed off the pipe,” Kruppa says.

Today, radiation is no longer discharging from his plant. Yet he remains concerned about where the leachate might now be going and, more broadly, about the weak regulation regarding radioactive waste that could end up in drinking water. The quarterly tests required of his sewage treatment plant, for example, do not include radium. “The old adage is, if you don’t test for it, you’re not going to find it,” adds Kruppa.

Concerns that radioactive elements from fracking could travel into community drinking water sources have been on the rise for at least a decade. A study led by Duke University researchers and published in 2013 found “potential environmental risks of radium bioaccumulation in localized areas of shale gas wastewater disposal.” Kruppa’s actions in 2018 drove widespread media attention to the issue.

In late July 2021, the state of Pennsylvania announced it would begin ordering landfills that accept waste from oil or gas drilling sites to test their leachate for certain radioactive materials associated with fracking. The state’s move was a “good step in the right direction,” says Amy Mall, a senior advocate with the nonprofit Natural Resources Defense Council, which published a report on radioactive waste from oil and gas production in July. “We do need more data. But we don’t think monitoring alone is adequate. We need stricter regulations as well.”

The EPA drinking water standard for radium-226 plus radium-228, the two most widespread isotopes of radium, is 5 picocuries per liter (0.26 gallon). The California Office of Environmental Hazard Assessment’s public health goal, set in 2006 and the basis of EWG’s study, is far more stringent: 0.05 picocuries per liter for radium-226 and just 0.019 picocuries per liter for radium-228. “There is a legal limit for some of these contaminants, like radium and uranium,” says Sydney Evans, a science analyst with EWG. “But, of course, that’s not necessarily what’s considered safe based on the latest research.”

“We don’t regulate for the most vulnerable,” says Arjun Makhijani, president of the nonprofit Institute for Energy and Environmental Research. He points to the first trimester in a pregnancy as among the riskiest windows of development.

The known toxicities of radioactive contaminants, as well as technology available to test for them, have evolved significantly since standards were established in the 1970s. “We have a rule limited by the technology available 40 years ago or more. It’s just a little crazy to me,” says Evans. Hirsch points to a series of reports from the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine on health risks from ionizing radiation. “They just keep finding that the same unit of exposure produces more cancers than had been presumed,” he says. The most recent version, published in 2006, found the risk of cancer due to radiation exposure for some elements to be about 35% higher per unit dose than the 1990 version.

The EPA has begun its fourth review of national primary drinking water regulations, in accordance with the Safe Drinking Water Act. The results are anticipated in 2023. While advocates hope for stricter standards, such changes would add to the difficulties many drinking water providers already face in finding the finances and technology necessary to meet those regulations.

Seeking solutions

The aquifer beneath Winona, Minnesota — which supplies drinking water to residents — naturally contains radium, resulting in challenges for the city water department to minimize levels of the radioactive element.

Tests of Winona’s drinking water have found levels of radium above federal standards. In response to results, in April 2021 city officials cautioned residents that low-dose exposure over many years can raise the risk of cancer. However, they did not advise people to avoid drinking the water.

The city is now looking to ramp up their use of a product called TonkaZorb, which has proven effective in removing radium at other drinking water plants, notes Brent Bunke, who served as the city’s water superintendent during the time of the testing. The product’s active ingredient is manganese, which binds to radium. The resulting clumps are easy to sift out by the sand filter. Local coverage aptly likened it to kitty litter. Bunke notes that the city also plans to replace the filter media in their aging sand filters. Of course, all these efforts are not cheap for the city. “It’s the cost of doing business,” says Bunke.

Winona is far from alone in their battle against ubiquitous radium. And they are unlikely to be the hardest hit. “Communities that are being impacted don’t necessarily have the means to fix it,” says Evans. “And it’s going to be a long-term, ongoing issue.” Over time, municipalities often have to drill deeper into the ground to find adequate water supply — where there tends to be even larger concentrations of radium.

Some are looking upstream for more equitable solutions. Stanford University researchers, for example, have identified a way to predict when and where uranium is released into groundwater aquifers. Dissolved calcium and alkalinity can boost water’s ability to pick up uranium, they found. Because this tends to happen in the top six feet of soil, drinking water managers can make sure that water bypasses that area as it seeps into or is pumped out of the ground.

The focus of this research has been on California’s Central Valley — an agricultural area rich in uranium. “When you start thinking about rural water systems, or you think about water that’s going to be used in agriculture, then your economic constraints become really, really great,” says Scott Fendorf, a professor of earth systems science at Stanford and coauthor on the study. “You can’t afford to do things like reverse osmosis” — a spendy form of filtration technology.

In general, radiation can be very difficult to remove from water. Reverse osmosis can be effective for uranium. Activated carbon can cut concentrations of radon and strontium. Yet standard home or water treatment plant filters are not necessarily going to remove all radioactive contaminants. Scientists and advocates underscore the need for further prevention strategies in the form of greater monitoring and stronger regulations. The push continues across the country, as the issue plagues nearly everywhere — an unfortunate truth that Knack now knows.

Why doesn’t her family simply move? “I’m not saying we won’t. I’m not saying we shouldn’t,” she says. “But I don’t even know where we’d go. It really looks like contaminated sites are not few, but all over the country.”

Small modular reactors will not save the day. The US can get to 100% clean power without new nuclear

We can create a renewable electricity system that is much more resilient to weather extremes and more reliable than what we have today.

https://www.utilitydive.com/news/small-modular-reactor-smr-wind-solar-battery-100-percent-clean-power-electricity/637372/ Nov. 28, 2022, By Arjun Makhijani

There is a widespread view that nuclear energy is necessary for decarbonizing the electricity sector in the United States. It is expressed not only by the nuclear industry, but also by scholars and policy-makers like former Energy Secretary Steven Chu, a Nobel Prize-winning physicist who recently said that the choices we have “…when the wind doesn’t blow and the sun doesn’t shine” are “fossil fuel or nuclear.” I disagree.

Wind and solar are much cheaper than new nuclear plants even when storage is added. The National Renewable Energy Laboratory estimated the cost of unsubsidized utility-scale solar plus battery storage in 2021 was $77 per megawatt-hour — about half the cost of new nuclear as estimated by the Wall Street firm Lazard. (An average New York State household uses a megawatt-hour in about seven weeks.)

Time is the scarcest resource of all for addressing the climate crisis. Nuclear has failed spectacularly on this count as well. Of the 34 new reactor projects announced for the “nuclear renaissance,” only two reactors being built in Georgia are set to come online — years late at more than double the initial cost estimate, a success rate of 6%. Even including the old Watts Bar 2 reactor (start of construction: 1973), which was completed in 2016 (well over budget), raises the success rate to just 9% — still much worse than the mediocre 50-50 record of the first round of nuclear construction in the U.S., when about half of the proposed reactors were ultimately built. The nuclear industry is marching fast — in the wrong direction.

The much-ballyhooed Small Modular Reactors are not going to save the day. NuScale, the most advanced in terms of certification, had announced in 2008 that its first reactor would be on line in 2015-2016; now the date is 2028 and costs have risen. In the same period, wind and solar generation have cumulatively generated electricity equal to more than the amount 300 NuScale SMRs would produce in 15 years. Nuclear is dismally slow, unequal to the climate challenge.

Simply saying that nuclear is “baseload power” is to recite an obsolete mantra. As David Olsen, a member of the Board of Governors of the California Independent System Operator, which runs that state’s electricity grid, has said: “‘Baseload’ refers to an old paradigm that has to go away.”

It is generally agreed that solar, wind and battery storage cannot address the entire decarbonization problem. They can do the job economically and reliably about 95% of the time. Much of the gap would be on winter nights with low wind when most buildings have electrified their heating and electric cars are plugged in. That’s where working with the rhythms of nature comes in.

Spring and autumn will be times of plentiful surplus wind and solar; that essentially free electricity could be used to make hydrogen to power light-duty fuel cells (such as those used in cars) to generate electricity on those cold winter nights. Surplus electricity can also be stored in the ground as cold or heat — artificial geothermal energy — for use during peak summer and winter hours.

Then there is V2G: vehicle-to-grid technology. When Hurricane Ian caused a blackout for millions in Florida, a Ford F-150 Lightning in “vehicle-to-home” mode saved the day for some. Plugged-in cars could have a dual purpose — as a load on the grid, or, for owners who sign up to profit, a supply resource for the grid, even as the charge for the commute next day is safeguarded.

We are also entering an era of smart appliances that can “talk” to the grid; it’s called “demand response.” The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission recognizes it as a resource equivalent to generation when many devices like cars or air conditioners are aggregated. People would get paid to sign up, and on those rare occasions when their heaters are lowered a degree or their clothes washing is postponed by a few hours, they would be paid again. No one would have to sign up; but signing up would make electricity cheaper. We know from experience there will be plenty of takers if the price is right.

All that is more than enough to take care of the 5% gap. No uranium mining, no nuclear waste, no plutonium produced just to keep the lights on.

We can create a renewable electricity system that is much more resilient to weather extremes and more reliable than what we have today. The thinking needs to change, as the Drake Landing Solar Community in Alberta, Canada, where it gets to negative 40 degrees Celsius in the winter, has shown. It provides over 90% of its heating by storing solar energy in the ground before the winter comes. Better than waiting for the nuclear Godot.

A pretentious and dishonest story-telling conference of Small Nuclear Reactor salesmen in Atlanta 2022

Markku Lehtonen in The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists covered this conference – “SMR & Advanced Reactor 2022” event in Atlanta – in a lengthy article.

The big players were there, among over 400 vendors, utility representatives, government officials, investors, and policy advocates, in “an atmosphere full of hope for yet another nuclear renaissance.

The writer details the claims and intentions of the SMR salesmen – in this “occasion for “team-building” and raising of spirits within the nuclear community.’, in relation to climate change and future energy needs, and briefly mentioning “security”, which is code for the nuclear weapons aspect.

It struck me that “team building” might be difficult, seeing that the industry representatives were from a whole heap of competing firms, with a whole heap of different small reactor designs, (and not all designs are even small, really)

This Bulletin article presents a measured discussion of the possibilities and the needs of the small nuclear reactors. The writer recognises that this gathering was really predominantly a showcase for the small nuclear wares, – the SMR salesmen “must promise, if not a radiant future, at least significant benefits to society. “

“Otherwise, investors, decision-makers, potential partners, and the public at large will not accept the inevitable costs and risks. Above all, promising is needed to convince governments to provide the support that has always been vital for the survival of the nuclear industry.”

He goes on to describe the discussions and concerns about regulation, needs for a skilled workforce, government support, economic viability. There were some contradictory claims about fast-breeder reactors.

Most interesting was the brief discussion on the political atmosphere, the role of governments, the question of over-regulation .

” A senior industry representative …. lamenting that the nuclear community has “allowed too much democracy to get in“

“The economic viability of the SMR promise will crucially depend on how much further down the road towards deglobalization, authoritarianism in its various guises, and further tweaking of the energy markets the Western societies are willing to go”

The Bulletin article concludes:

“Promises and counter-promises. For the SMR community that gathered in Atlanta, the conference was a moment of great hope and opportunity, not least thanks to the aggravating climate and energy security crises. But the road toward the fulfilment of the boldest SMR promises will be long, as is the list of the essential preconditions. To turn SMR promises into reality, the nuclear community will need no less than to achieve sufficient internal cohesion, attract investors, navigate through licensing processes, build up supply chains and factories for module manufacturing, win community acceptance on greenfield sites, demonstrate a workable solution to waste management, and reach a rate of deployment sufficient to trigger learning and generate economies of replication. Most fundamentally, governments would need to be persuaded to provide the many types of support SMRs require to deliver on their promises.

Promising of the kind seen at the conference is essential for the achievement of these objectives. The presentations and discussions in the corridors indeed ran the full gamut of promise-building, from the conviction of a dawning nuclear renaissance along the lines “this time, it will be different!” through the hope of SMRs as a solution to the net-zero and energy-security challenges, and all the way to specific affirmations hailing the virtues of individual SMR designs. The legitimacy and credibility of these claims were grounded in the convictions largely shared among the participants that renewables alone “just don’t cut it,” that the SMR supply chain is there, and that the nuclear industry has in the past shown its ability to rise to similar challenges.

Two questions appear as critical for the future of SMRs. First, despite the boost from the Ukraine crisis, it is uncertain whether SMR advocates can muster the political will and societal acceptance needed to turn SMRs into a commercial success. The economic viability of the SMR promise will crucially depend on how much further down the road towards deglobalization, authoritarianism in its various guises, and further tweaking of the energy markets the Western societies are willing to go. Although the heyday of neoliberalism is clearly behind us and government intervention is no longer the kind of swearword it was before the early 2000s, nothing guarantees that the nuclear euphoria following the Atoms for Peace program in the 1950s can be replicated. Moreover, the reliance of the SMR business case on complex global supply chains as well as on massive deployment and geographical dispersion of nuclear facilities creates its own geopolitical vulnerabilities and security problems.

Second, the experience from techno-scientific promising in a number of sectors has shown that to be socially robust, promises need constructive confrontation with counter-promises. In this regard, the Atlanta conference constituted somewhat of a missed opportunity. The absence of critical voices reflected a longstanding problem of the nuclear community recognized even by insiders—namely its unwillingness to embrace criticism and engage in constructive debate with sceptics. “Safe spaces” for internal debates within a like-minded community certainly have their place, yet in the current atmosphere of increasing hype, the SMR promise needs constructive controversy and mistrust more than ever.” https://thebulletin.org/2022/12/building-promises-of-small-modular-reactors-one-conference-at-a-time

How Ukraine’s Jewish president Zelensky made peace with neo-Nazi paramilitaries on front lines of war with Russia

In its bid to deflect from the influence of Nazism in contemporary Ukraine, US media has found its most effective PR tool in the figure of Zelensky, a former TV star and comedian from a Jewish background. It is a role the actor-turned-politician has eagerly assumed.

But as we will see, Zelensky has not only ceded ground to the neo-Nazis in his midst, he has entrusted them with a front line role in his country’s war against pro-Russian and Russian forces.

The Grayzone, ALEXANDER RUBINSTEIN AND MAX BLUMENTHAL·MARCH 4, 2022

While Western media deploys Volodymyr Zelensky’s Jewish heritage to refute accusations of Nazi influence in Ukraine, the president has ceded to neo-Nazi forces and now depends on them as front line fighters.

Back in October 2019, as the war in eastern Ukraine dragged on, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky traveled to Zolote, a town situated firmly in the “gray zone” of Donbas, where over 14,000 had been killed, mostly on the pro-Russian side. There, the president encountered the hardened veterans of extreme right paramilitary units keeping up the fight against separatists just a few miles away.

Elected on a platform of de-escalation of hostilities with Russia, Zelensky was determined to enforce the so-called Steinmeier Formula conceived by then-German Foreign Minister Walter Steinmeier which called for elections in the Russian-speaking regions of Donetsk and Lugansk.

In a face-to-face confrontation with militants from the neo-Nazi Azov Battalion who had launched a campaign to sabotage the peace initiative called “No to Capitulation,” Zelensky encountered a wall of obstinacy.

With appeals for disengagement from the frontlines firmly rejected, Zelensky melted down on camera. “I’m the president of this country. I’m 41 years old. I’m not a loser. I came to you and told you: remove the weapons,” Zelensky implored the fighters.

Once video of the stormy confrontation spread across Ukrainian social media channels, Zelensky became the target of an angry backlash.

Andriy Biletsky, the proudly fascist Azov Battalion leader who once pledged to “lead the white races of the world in a final crusade…against Semite-led Untermenschen”, vowed to bring thousands of fighters to Zolote if Zelensky pressed any further. Meanwhile, a parliamentarian from the party of former Ukrainian President Petro Poroshenko openly fantasized about Zelensky being blown to bits by a militant’s grenade.

Though Zelensky achieved a minor disengagement, the neo-Nazi paramilitaries escalated their “No Capitulation” campaign. And within months, fighting began to heat up again in Zolote, sparking a new cycle of violations of the Minsk Agreement.

By this point, Azov had been formally incorporated into the Ukrainian military and its street vigilante wing, known as the National Corps, was deployed across the country under the watch of the Ukrainian Interior Ministry, and alongside the National Police. In December 2021, Zelensky would be seen delivering a “Hero of Ukraine” award to a leader of the fascistic Right Sector in a ceremony in Ukraine’s parliament.

A full-scale conflict with Russia was approaching, and the distance between Zelensky and the extremist paramilitaries was closing fast.

This February 24, when Russian President Vladimir Putin sent troops into Ukrainian territory on a stated mission to “demilitarize and denazify” the country, US media embarked on a mission of its own: to deny the power of neo-Nazi paramilitaries over the country’s military and political sphere. As the US government-funded National Public Radio insisted, “Putin’s language [about denazification] is offensive and factually wrong.”

In its bid to deflect from the influence of Nazism in contemporary Ukraine, US media has found its most effective PR tool in the figure of Zelensky, a former TV star and comedian from a Jewish background. It is a role the actor-turned-politician has eagerly assumed.

But as we will see, Zelensky has not only ceded ground to the neo-Nazis in his midst, he has entrusted them with a front line role in his country’s war against pro-Russian and Russian forces.

The president’s Jewishness as Western media PR device

Hours before President Putin’s February 24 speech declaring denazification as the goal of Russian operations, Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky “asked how a people who lost eight million of its citizens fighting Nazis could support Nazism,” according to the BBC.

Raised in a non-religious Jewish family in the Soviet Union during the 1980’s, Zelensky has downplayed his heritage in the past. “The fact that I am Jewish barely makes 20 in my long list of faults,” he joked during a 2019 interview in which he declined to go into further detail about his religious background.

Today, as Russian troops bear down on cities like Mariupol, which is effectively under the control of the Azov Battalion, Zelensky is no longer ashamed to broadcast his Jewishness. “How could I be a Nazi?” he wondered aloud during a public address. For a US media engaged in an all-out information war against Russia, the president’s Jewish background has become an essential public relations tool.

A few examples of the US media’s deployment of Zelensky as a shield against allegations of rampant Nazism in Ukraine are below (see mash-up above [on original] for video ): ………………………………….

Behind the corporate media spin lies the complex and increasingly close relationship Zelensky’s administration has enjoyed with the neo-Nazi forces invested with key military and political posts by the Ukrainian state, and the power these open fascists have enjoyed since Washington installed a Western-aligned regime through a coup in 2014.

In fact, Zelensky’s top financial backer, the Ukrainian Jewish oligarch Igor Kolomoisky, has been a key benefactor of the neo-Nazi Azov Battalion and other extremists militias.

Backed by Zelensky’s top financier, neo-Nazi militants unleash a wave of intimidation

Incorporated into the Ukrainian National Guard, the Azov Battalion is considered the most ideologically zealous and militarily motivated unit fighting pro-Russian separatists in the eastern Donbass region.

With Nazi-inspired Wolfsangel insignia on the uniforms of its fighters, who have been photographed with Nazi SS symbols on their helmets, Azov “is known for its association with neo-Nazi ideology…[and] is believed to have participated in training and radicalizing US-based white supremacy organizations,” according to an FBI indictment of several US white nationalists that traveled to Kiev to train with Azov.

Igor Kolomoisky, a Ukrainian energy baron of Jewish heritage, has been a top funder of Azov since it was formed in 2014. He has also bankrolled private militias like the Dnipro and Aidar Battalions, and has deployed them as a personal thug squad to protect his financial interests.

In 2019, Kolomoisky emerged as the top backer of Zelensky’s presidential bid. Though Zelensky made anti-corruption the signature issue of his campaign, the Pandora Papers exposed him and members of his inner circle stashing large payments from Kolomoisky in a shadowy web of offshore accounts.

When Zelensky took office in May 2019, the Azov Battalion maintained de facto control of the strategic southeastern port city of Mariupol and its surrounding villages. As Open Democracy noted, “Azov has certainly established political control of the streets in Mariupol. To maintain this control, they have to react violently, even if not officially, to any public event which diverges sufficiently from their political agenda.”

Attacks by Azov in Mariupol have included assaults on “feminists and liberals” marching on International Women’s Day among other incidents……………………………

Zelensky failed to rein in neo-Nazis, wound up collaborating with them

Following his failed attempt to demobilize neo-Nazi militants in the town of Zolote in October 2019, Zelensky called the fighters to the table, telling reporters “I met with veterans yesterday. Everyone was there – the National Corps, Azov, and everyone else.”

A few seats away from the Jewish president was Yehven Karas, the leader of the neo-Nazi C14 gang.

During the Maidan “Revolution of Dignity” that ousted Ukraine’s elected president in 2014, C14 activists took over Kiev’s city hall and plastered its walls with neo-Nazi insignia before taking shelter in the Canadian embassy.

As the former youth wing of the ultra-nationalist Svoboda Party, C14 appears to draw its name from the infamous 14 words of US neo-Nazi leader David Lane: “We must secure the existence of our people and a future for white children.”………………………………………………..

Throughout 2019, Zelensky and his administration deepened their ties with ultra-nationalist elements across Ukraine…………………………………………………………

In November 2021, one of Ukraine’s most prominent ultra-nationalist militiamen, Dmytro Yarosh, announced that he had been appointed as an advisor to the Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces of Ukraine. Yarosh is an avowed follower of the Nazi collaborator Bandera who led Right Sector from 2013 to 2015, vowing to lead the “de-Russification” of Ukraine…………………………………….

Ukrainian state-backed neo-Nazi leader flaunts influence on the eve of war with Russia

On February 5, 2022, only days before full-scale war with Russia erupted, Yevhen Karas of the neo-Nazi C14 delivered a stem-winding public address in Kiev intended to highlight the influence his organization and others like it enjoyed over Ukrainian politics………………………………….

“If we get killed…we died fighting a holy war”

…………………………………… With fighting underway, Azov’s National Corps gathered hundreds of ordinary civilians, including grandmothers and children, to train in public squares and warehouses from Kharviv to Kiev to Lviv.

On February 27, the official Twitter account of the National Guard of Ukraine posted video of “Azov Fighters” greasing their bullets with pig fat to humiliate Russian Muslim fighters from Chechnya.

…………………… Besides authorizing the release of hardcore criminals to join the battle against Russia, Zelensky has ordered all males of fighting age to remain in the country. Azov militants have proceeded to enforce the policy by brutalizing civilians attempting to flee from the fighting around Mariupol.

According to one Greek resident in Mariupol recently interviewed by a Greek news station, “When you try to leave you run the risk of running into a patrol of the Ukrainian fascists, the Azov Battalion,” he said, adding “they would kill me and are responsible for everything.”

Footage posted online appears to show uniformed members of a fascist Ukrainian militia in Mariupol violently pulling fleeing residents out of their vehicles at gunpoint.

Other video filmed at checkpoints around Mariupol showed Azov fighters shooting and killing civilians attempting to flee.

On March 1, Zelensky replaced the regional administrator of Odessa with Maksym Marchenko, a former commander of the extreme right Aidar Battalion, which has been accused of an array of war crimes in the Donbass region.

Meanwhile, as a massive convoy of Russian armored vehicles bore down on Kiev, Yehven Karas of the neo-Nazi C14 posted a video on YouTube from inside a vehicle presumably transporting fighters.

“If we get killed, it’s fucking great because it means we died fighting a holy war,” Karas exclaimed. ”If we survive, it’s going to be even fucking better! That’s why I don’t see a downside to this, only upside!”

https://thegrayzone.com/2022/03/04/nazis-ukrainian-war-russia/

Despite the hype, we shouldn’t bank on nuclear fusion to save the world from climate catastrophe

Robin McKie, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2022/dec/17/dont-bank-on-nuclear-fusion-to-save-the-world-from-a-climate-catastrophe-i-have-seen-it-all-before

Last week’s experiment in the US is promising, but it’s not a magic bullet for our energy needs

“…….. For almost half a century, I have reported on scientific issues and no decade has been complete without two or three announcements by scientists claiming their work would soon allow science to recreate the processes that drive the sun. The end result would be the generation of clean, cheap nuclear fusion that would transform our lives.

Such announcements have been rare recently, so it gave me a warm glow to realise that standards may be returning to normal. By deploying a set of 192 lasers to bombard pellets of the hydrogen isotopes deuterium and tritium, researchers at the US National Ignition Facility (NIF) in Livermore, California, were able to generate temperatures only found in stars and thermonuclear bombs. The isotopes then fused into helium, releasing excess energy, they reported.

It was a milestone event but not a major one, although this did not stop the US government and swaths of the world’s media indulging in a widespread hyping jamboree over the laboratory’s accomplishment. Researchers had “overcome a major barrier” to reaching fusion, the BBC gushed, while the Wall Street Journal described the achievement as a breakthrough that could herald an era of clean, cheap energy.

It is certainly true that nuclear fusion would have a beneficial impact on our planet by liberating vast amounts of energy without generating high levels of carbon emissions and would be an undoubted boost in the battle against climate change.

The trouble is that we have been presented with such visions many times before. In 1958, Sir John Cockcroft claimed his Zeta fusion project would supply the world with “an inexhaustible supply of fuel”. It didn’t. In 1989, Martin Fleischmann and Stanley Pons announced they had achieved fusion using simple laboratory equipment, work that made global headlines but which has never been replicated.

To this list you can also add the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (Iter), a huge facility being built in Saint-Paul-lès-Durance in Provence, France, that was supposed to achieve fusion by 2023 but which is over 10 years behind schedule and tens of billions of dollars over budget.

In each case, it was predicted that the construction of the first commercially viable nuclear fusion plants was only a decade or two away and would transform our lives. Those hopes never materialised and have led to a weary cynicism spreading among hacks and scientists. As they now joke: “Fusion is 30 years away – and always will be.”

It was odd for Jennifer Granholm, the US energy secretary, to argue that the NIF’s achievement was “one of the most impressive scientific feats of the 21st century”. This is a hard claim to justify for a century that has already witnessed the discovery of the Higgs boson, the creation of Covid-19 vaccines, the launch of the James Webb telescope and the unravelling of the human genome. By comparison, the ignition event at the NIF is second-division stuff.

Most scientists have been careful in their responses to the over-hyping of the NIF “breakthrough”. They accept that a key step has been taking towards commercial fusion power but insist such plants remain distant goals. They should not be seen as likely saviours that will extract us from the desperate energy crisis we now face – despite all the claims that were made last week.

Humanity has brought itself to a point where its terrible dependence on fossil fuels threatens to trigger a 2C jump in global temperatures compared with our pre-industrial past. The consequences will include flooding, fires, worsening storms, rising sea levels, spreading diseases and melting ice caps.

Here, scientists are clear. Fusion power will not arrive in time to save the world. “We are still a way off commercial fusion and it cannot help us with the climate crisis now,” said Aneeqa Khan, a research fellow in nuclear fusion at Manchester University. This view was backed by Tony Roulstone, a nuclear energy researcher at Cambridge University. “This result from NIF is a success for science, but it is still a long way from providing useful, abundant clean energy.”

At present, there are two main routes to nuclear fusion. One involves confining searing hot plasma in a powerful magnetic field. The Iter reactor follows such an approach. The other – adopted at the NIF facility – uses lasers to blast deuterium-tritium pellets causing them to collapse and fuse into helium. In both cases, reactions occur at more than 100 million C and involve major technological headaches in controlling them.

Fusion therefore remains a long-term technology, although many new investors and entrepreneurs – including Bill Gates and Jeff Bezos – have recently turned their attention to the field, raising hopes that a fresh commercial impetus could reinvigorate the development of commercial plants.

This input is to be welcomed but we should be emphatic: fusion will not arrive in time to save the planet from climate change. Electricity plants powered by renewable sources or nuclear fission offer the only short-term alternatives to those that burn fossil fuels. We need to pin our hopes on these power sources. Fusion may earn its place later in the century but it would be highly irresponsible to rely on an energy source that will take at least a further two decades to materialise – at best.

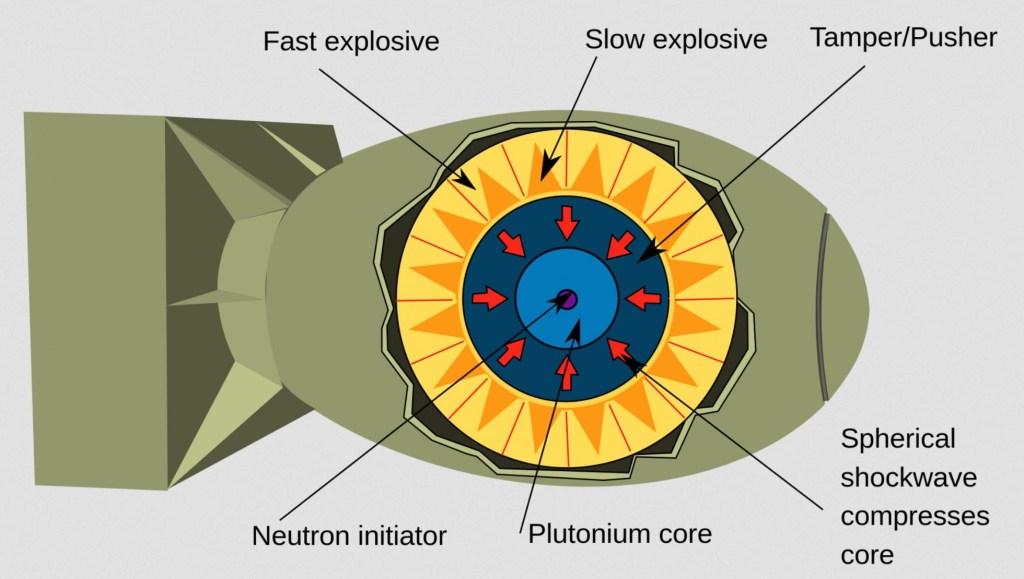

America’s complicated problem of disposing of tons of plutonium bomb cores, as the government to spend $1.7 billion on more plutonium bomb cores

The nuclear security agency’s draft statement comes as the Senate approved a military spending bill that seeks to funnel $1.7 billion to the lab’s pit operations, an unprecedented funding amount.

Weehler said the government should hold off on producing pits, which will generate more waste, until it has figured out a safe and effective way to dispose of the radioactive material it already has.

LANL would aid in diluting plutonium in controversial disposal plan

https://www.santafenewmexican.com/news/local_news/lanl-would-aid-in-diluting-plutonium-in-controversial-disposal-plan/article_e6cb6380-6d26-11ed-9a6c-731a070c9235.html By Scott Wyland swyland@sfnewmexican.com, Dec 17, 2022

The federal government has released a draft environmental impact statement on its plans to dilute and dispose of surplus plutonium, plans that worry some activists, residents and state officials because the radioactive material would be trucked at least twice through New Mexico, including the southern edge of Santa Fe.

The U.S. Energy Department’s nuclear security agency placed a notice of the 412-page draft in the Federal Register on Friday, providing details on the plutonium disposal it first announced two years ago but had kept mostly silent about.

Agencies want to get rid of 34 metric tons of plutonium bomb cores, or pits, that are left over from the Cold War and being kept at the Pantex Plant in Amarillo, Texas.

Plans call for shipping the material to Los Alamos National Laboratory, where it would be converted to oxidized powder, then transported to Savannah River Site in South Carolina so crews can add an adulterant to make it unusable for weapons.

From there, it would go to the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant, an underground disposal site in Carlsbad. This “downblending” is required because WIPP only takes waste below a certain radioactive level.

The public will have a chance to weigh in, both with written comments and at several public hearings scheduled for early next year.

Critics have spoke out against the plan for more than a year, arguing it puts communities along the trucking routes at risk and should be reconsidered.

Cindy Weehler, who co-chairs the watchdog group 285 ALL, said the environmental review confirms her concerns about the region becoming a hub for material that is more radioactive than the transuranic waste — contaminated gloves, equipment, clothing, soil and other materials — the lab now ships to WIPP.

“The preferred option is still to do this 3,300-hundred-mile road trip and have the two operations occur at two different labs,” Weehler said.

The impact statement offers possible alternatives, such as doing all the downblending at the lab or Savannah River to reduce transportation, but it makes clear the original plan is the preferred method.

The National Nuclear Security Administration has been quiet about the dilute-and-dispose plans, other than to acknowledge an environmental impact statement was underway.

This silence has frustrated residents, state and local officials and community advocates like Weehler.

If all the downblending is done at the lab, it would keep the plutonium from being hauled through a dozen states, so that would be better for many neighborhoods across the country, Weehler said.

However, dangerous radioactive substances would still go through Los Alamos and Santa Fe counties twice, she said.

Whether the oxidized powder leaves the lab in pure form or is adulterated, it would be hazardous to breathe in if the containers were breached in an accident, she said.

The draft statement said the powder would go into a steel canister, which would be placed into a reinforced 55-gallon drum known as a “criticality control container.” As many as 14 control containers can be put into a heavily fortified Trupact shipping container.

The lab has an operation known as ARIES for oxidizing plutonium on a small scale. Boosting the quantity would require installing more glove boxes — the sealed compartments that allow workers to handle radioactive materials — and other equipment to the plutonium facility, the statement said. The additions would expand the facility to 6,800 feet from 5,200 feet.

Structures would have to be built to accommodate the work, including a logistical support center, an office building, a warehouse, a security portal and a weather enclosure for the plutonium facility’s loading dock, the statement says.

The idea of doing away with surplus plutonium began after the Cold War. In 2000, the U.S. and Russia agreed to each eliminate 34 metric tons of the plutonium so it could no longer be used in nuclear weapons.

Russia reportedly withdrew from the pact later, but the U.S. decided to stick with its commitment.

The Energy Department originally sought to build a Savannah River facility that could turn Cold War plutonium into a mixed oxide fuel for commercial nuclear plants. But after billions of dollars in cost overruns and years of delays, the Trump administration scrapped the project in 2018 and decided to go with diluting and disposing of the waste.

One nuclear waste watchdog questioned why the leftover pits must be removed from Pantex at all.

That facility should be able to continue storing the plutonium safely, just as it has since the 1990s, said Don Hancock, director of nuclear waste safety for the nonprofit Southwest Research and Information Center.

“If it’s not safe to be at Pantex, then that raises some severe questions about the safety of the Pantex plant for its assembly and disassembly mission” for nuclear weapons, Hancock said.

Hancock said he opposes the government using WIPP as the sole disposal site for the diluted plutonium and other nuclear waste.

The nuclear security agency’s draft statement comes as the Senate approved a military spending bill that seeks to funnel $1.7 billion to the lab’s pit operations, an unprecedented funding amount.

Weehler said the government should hold off on producing pits, which will generate more waste, until it has figured out a safe and effective way to dispose of the radioactive material it already has.

“This is just a commonsense thing,” she said. “We have the weaponry we need.”

Fusion. Really?

BY KARL GROSSMAN, https://www.counterpunch.org/2022/12/16/fusion-really/— 16 Dec 22

There was great hoopla—largely unquestioned by media—with the announcement this week by the U.S. Department of Energy of a “major scientific breakthrough” in the development of fusion energy.

“This is a landmark achievement,” declared Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm. Her department’s press release said the experiment at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California “produced more energy from fusion than the laser energy used to drive it” and will “provide invaluable insights into the prospects of clean fusion energy.”

“Nuclear fusion technology has been around since the creation of the hydrogen bomb,” noted a CBS News article covering the announcement. “Nuclear fusion has been considered the holy grail of energy creation.” And “now fusion’s moment appears to be finally here,” said the CBS piece

But, as Dr. Daniel Jassby, for 25 years principal research physicist at the Princeton Plasma Physics Lab working on fusion energy research and development, concluded in a 2017 article in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, fusion power “is something to be shunned.”

His article was headed “Fusion reactor: Not what they’re cracked up to be.”

“Fusion reactors have long been touted as the ‘perfect’ energy source,” he wrote. And “humanity is moving much closer” to “achieving that breakthrough moment when the amount of energy coming out of a fusion reactor will sustainably exceed the amount going in, producing net energy.”

“As we move closer to our goal, however,” continued Jassby, “it is time to ask: Is fusion really a ‘perfect’ energy source?” After having worked on nuclear fusion experiments for 25 years at the Princeton Plasma Physics Lab, I began to look at the fusion enterprise more dispassionately in my retirement. I concluded that a fusion reactor would be far from perfect, and in some ways close to the opposite.”

“Unlike what happens” when fusion occurs on the sun, “which uses ordinary hydrogen at enormous density and temperature,” on Earth “fusion reactors that burn neutron-rich isotopes have byproducts that are anything but harmless,” he said.

A key radioactive substance in the fusion process on Earth would be tritium, a radioactive variant of hydrogen.

Thus there would be “four regrettable problems”—“radiation damage to structures; radioactive waste; the need for biological shielding; and the potential for the production of weapons-grade plutonium 239—thus adding to the threat of nuclear weapons proliferation, not lessening it, as fusion proponents would have it,” wrote Jassby.

“In addition, if fusion reactors are indeed feasible…they would share some of the other serious problems that plague fission reactors, including tritium release, daunting coolant demands, and high operating costs. There will also be additional drawbacks that are unique to fusion devices: the use of a fuel (tritium) that is not found in nature and must be replenished by the reactor itself; and unavoidable on-site power drains that drastically reduce the electric power available for sale.”

“The main source of tritium is fission nuclear reactors,” he went on. Tritium is produced as a waste product in conventional nuclear power plants. They are based on the splitting of atoms, fission, while fusion involves fusing of atoms.

“If adopted, deuterium-tritium based fusion would be the only source of electrical power that does not exploit a naturally occurring fuel or convert a natural energy supply such as solar radiation, wind, falling water, or geothermal. Uniquely, the tritium component of fusion fuel must be generated in the fusion reactor itself,” said Jassby.

About nuclear weapons proliferation, “The open or clandestine production of plutonium 239 is possible in a fusion reactor simply by placing natural or depleted uranium oxide at any location where neutrons of any energy are flying about. The ocean of slowing-down neutrons that results from scattering of the streaming fusion neutrons on the reaction vessel permeates every nook and cranny of the reactor interior, including appendages to the reaction vessel.”