Japan’s election campaign – Liberal Democratic Party candidates’ differing views on nuclear recycling.

Three of the four candidates vying to lead the Liberal Democratic Party

called Sunday for Japan to maintain its nuclear fuel recycling program as

they geared up for the last few days of campaigning prior to Wednesday’s

vote. During a Fuji TV program, vaccination minister Taro Kono, the only

contender who has pushed for phasing out nuclear power generation, went

against his leadership rivals and said Japan should pivot away from fuel

recycling “as soon as possible.”

Japan Times 26th Sept 2021

https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2021/09/26/national/ldp-hopefuls-nuclear-fuel/

Will Fukushima’s Water Dump Set a Risky Precedent?

Will Fukushima’s Water Dump Set a Risky Precedent? IEEE Spectrum

Questions raised over new norms the disaster’s radioactive wastewater cleanup efforts may foster, RAHUL RAO 24 SEP 2021 Since the Japanese earthquake and tsunami in March 2011, groundwater has been trickling through the damaged facilities at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant, filtering through the melted cores and fuel rods and becoming irradiated with a whole medley of radioisotopes. Japanese authorities have been pumping that water into a vast array of tanks on-site: currently over a thousand tanks, and adding around one new tank per week.

Now, Japanese authorities are preparing to release that water into the Pacific Ocean. Even though they’re treating and diluting the water first, the plan is meeting with vocal protests. From that opposition and from scientists’ critiques of the process, the ongoing events at Fukushima leave an unprecedented example that other nuclear power facilities can watch and learn from.

The release is slated to start in 2023, and potentially last for decades. This month, observers from the International Atomic Energy Agency have arrived in the country to inspect the process. And efforts are also underway to build an undersea tunnel that will discharge the water a kilometer away from the shore.

Before they do that, they’ll treat the water to cleanse it of radioactive contaminants. According to the authorities’ account of the situation, there’s one major contaminant that their system cannot cleanse: tritium.

It’s actually normal for nuclear power plants to release tritium into the air and water in their normal operations. In fact, pre-disaster, Fukushima Daiichi held boiling-water reactors, the lowest-tritium type of nuclear reactors. The Japanese government’s solution is to dilute the tritium-contaminated water down to comparable levels. That’s part of the reason the discharge will likely last several decades.

“While one can argue whether such release limits are appropriate in general for normally operating facilities, the planned release, if carried out correctly, does not appear to be outside of the norm,” says Edwin Lyman, director of nuclear power safety at the Union of Concerned Scientists.

Even so, the plan has—perhaps expectedly—encountered some rather vocal opposition. Some of the loudest cries have come from within Japan, particularly from the fishing industry. Radiation levels in seafood from that coast are well within safety limits, but fishing cooperatives are concerned the plan is (once again) putting their reputations at stake………….

can the events at Fukushima offer other energy facilities around the world any lessons at all?

For one, they’re a good show of the need for emergency planning. “Every nuclear plant should be required to analyze the potential for such long-term consequences,” says Lyman. “New nuclear plants, if built, should incorporate such evaluations into their siting decisions.”

But there’s other things experts say that facilities could learn. For example, something that hasn’t always been present in the Fukushima matter—working against it—has been transparency.

Authorities at the plant haven’t fully addressed the matter of non-tritium contaminants, according to Ken Buesseler, a marine radiochemist at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution who has studied radioactivity in the ocean off Fukushima. Some contaminants—like caesium-137 and strontium-90—were present in the initial disaster in 2011. Others—like cobalt-60 and cerium-144—entered the water later.

It isn’t something the authorities have completely ignored. “Japan plans to run the water again through the decontamination process before release, and the dilution will further reduce the concentrations of the remaining isotopes,” says Lyman.

But Buesseler isn’t convinced that it will be enough. “Theoretically, it’s possible to improve the situation a lot,” he says. “In practice, they haven’t done that.” Japanese authorities insist they can do so, but their ability, he says, hasn’t been independently verified and peer-reviewed……….

“I’d hate to see every country that has radioactive waste start dumping waste into the ocean,” he says. “It’s a transboundary issue, in a way. It’s something bigger than Japan, and something different from regular operation. I think they need to be at least open about that, getting international approval.”

Here, Lyman agrees. “This situation is unique and the decision to release the water into the sea should not set a precedent for any other project.”

But even taking all of that into account, some believe that, if anything, this is an example of a time when there simply is no choice but to take drastic action.

“I believe that this action is necessary to avoid potentially worse consequences,” says Lyman. https://spectrum.ieee.org/fukushima-wastewater-cleanup-questions

Nuclear submarine for Japan? Kono says yes, Kishida says no

Nuclear submarine for Japan? Kono says yes, Kishida says no Nikkei Asia Poll leader believes capability is ‘extremely important’ for country. YUSUKE TAKEUCHI, Nikkei staff writer, September 26, 2021

TOKYO — Following a recent deal by the U.S. and the U.K. to offer Australia classified technology to build nuclear-powered submarines, should fellow Quad member Japan also seek such a capability? The four candidates running for the Liberal Democratic Party presidential race to succeed Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga were asked the question Sunday on Fuji TV.

Poll leader Taro Kono, minister for administrative reform and also in charge of vaccine distribution, gave a thumbs-up. “As a capability, it is very important for Japan to have nuclear submarines,” he said……..

Sanae Takaichi, the former internal affairs minister, also looked favorably upon the idea. “If we think of the worst-case risks in the international environment ahead, I do believe we could have [submarines] that can travel a little longer,” she said, referring to the advantage of nuclear propulsion in that they can stay submerged longer without refueling.

Japan’s Atomic Energy Basic Law stipulates that the use of nuclear power will be limited to peaceful purposes. Takaichi said there was “a need to sort things out” but added she did not believe nuclear-powered submarines to be unconstitutional.

Former LDP policy chief Fumio Kishida, meanwhile, was less receptive to the idea. “When I think about Japan’s national security arrangements, to what extent do we need it?” he asked.

Nuclear-powered submarines are faster and can travel longer compared to the diesel-electric submarines that Japan currently has. But Kishida was alluding to the fact that the Self-Defense Forces’ operations are primarily in areas close to Japan.

To maintain stealth, it will require long hours of work,” he said. “We have to prioritize improving working conditions [of sailors] and secure the personnel.”…….

Seiko Noda, the LDP’s executive acting secretary-general, said: “I have no intention to hold such a capability. I want to make clear that we are a nation with three non-nuclear principles,” she said, pointing to Japan’s long-held position of neither possessing nor manufacturing nuclear weapons, nor permitting their introduction into Japanese territory.

“This is not a situation where we can immediately buy and start to use the submarines,” she said. “We must properly establish a national consensus.” ……. https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/Nuclear-submarine-for-Japan-Kono-says-yes-Kishida-says-no

LDP candidates debate on nuke power must be based on realities

September 24, 2021

Japan’s nuclear power policy has emerged as one of the main issues for the ruling Liberal Democratic Party’s leadership race.

The four candidates for the party presidential election on Sept. 29 should face up to the lessons from the disaster that unfolded at Tokyo Electric Power Co.’s Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant a decade ago and offer specific policy proposals for ensuring in-depth debate on key questions.

Taro Kono, the minister of administrative reform who also served as foreign and defense minister in the past, is the only one among the contenders who has clearly argued for phasing out nuclear power generation.

Kono has stated that Japan should pull the plug on its nuclear fuel recycling program “as soon as possible” while promising to allow offline reactors to be restarted when they are officially endorsed as safe, for the time being.

The other three politicians seeking to succeed outgoing Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga have committed themselves to maintaining the current policy of keeping nuclear reactors running. During a recent debate, they voiced skepticism about Kono’s vow to end the fuel recycling program.

Fumio Kishida, a former foreign minister and LDP policy chief, questioned the consistency between Kono’s position on fuel recycling and his policy of allowing reactors to be brought on stream.

Seiko Noda, executive acting secretary-general of the LDP, ruled out any energy policy change that could cause a disruption in the stable supply of power. Sanae Takaichi, a former communications minister, stressed she would promote the development of small reactors and nuclear fusion reactor technology.

The nuclear fuel recycling process involves recovering plutonium from spent nuclear fuel for recycling back into new fuel.

But Japan’s original plan to reprocess spent nuclear fuel to obtain start-up plutonium for a new generation of plutonium “fast breeder” reactors fell through when its Monju prototype fast breeder reactor, which was supposed to be the core technology for the program, was shut down after a sodium leak and fire.

The government then shifted to a strategy of converting spent plutonium, formed in nuclear reactors as a by-product of burning uranium fuel, and uranium into a “mixed oxide” (MOX) that can be reused in existing reactors to produce more electricity.

But this approach has also hit a snag as the number of operating reactors has declined sharply since the Fukushima meltdowns.

Asahi Shimbun editorials have argued that the government should concede that the fuel recycling program is no longer viable and declare an end to it. To be sure, withdrawing from the program would mean spent nuclear fuel must be disposed of as waste. But Japan would only make the world uneasy if it keeps a massive stockpile of weapons-usable plutonium without any plan to use it.

Arguments concerning nuclear policy issues in general, not just fuel recycling, tend to overlook reality. The most important fact about the catastrophic accident at the Fukushima plant is that it caused tremendous damage to society.

Not much is known about the current conditions of the reactors whose cores melted down during the accident. There is no predicting when and how the process of decommissioning the plant will come to an end.

The LDP presidential candidates are divided over whether to build new nuclear plants or expand current ones. But it is obvious that winning the support of the public in general and the local communities involved for such plans would be next to impossible.

It is also unclear when the small reactor and the nuclear fusion reactor that are under development will enter commercial use.

A new estimate by the industry ministry on the future costs of power generation published in August predicts that solar power will eclipse nuclear energy in terms of costs as of 2030. It is hardly surprising that the government’s draft new Basic Energy Plan, unveiled in July, says promoting renewable energy sources should be the top energy policy priority.

Since the Fukushima disaster, the government has been seeking to restart offline reactors one by one while leaving the decisions up to the Nuclear Regulation Authority. But the government should not shy away from a sweeping review of its broken nuclear energy policy.

There are many sticky questions the LDP presidential hopefuls need to address. How would they try to change the country’s current energy mix in what ways and in what kind of time frames while maintaining a steady power supply? What would they do with the growing amount of spent nuclear fuel?

The LDP election requires them to clarify their approaches to tackling these tough challenges.

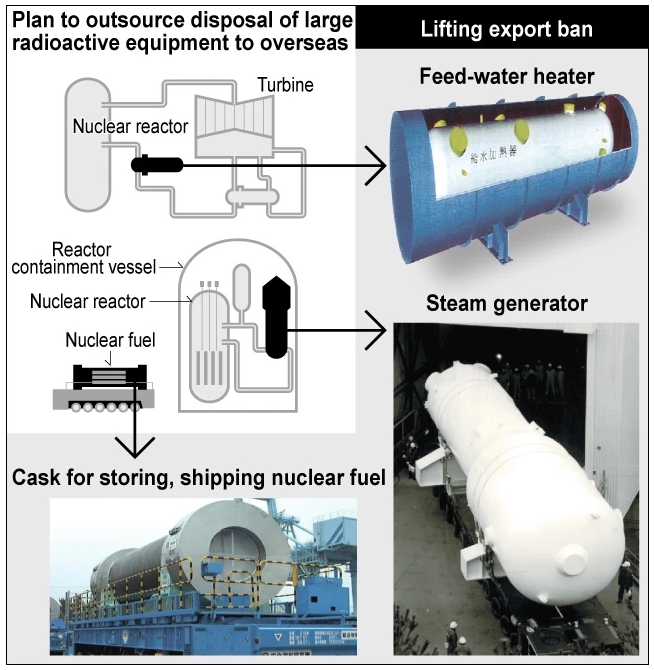

Japan eyes disposal abroad of radioactive plant equipment

Watch out! Japan’s hoping to export now its radioactive junk!

September 20, 2021

Japan plans to ease regulations to allow exports of large, disused equipment from nuclear power plants for overseas disposal as a way to reduce the mountains of radioactive waste accumulating at home.

The setup would mark a major shift from the government’s existing principle of disposing of all radioactive waste inside the country.

The industry ministry mentioned the revised disposal policy in the draft of the updated Basic Energy Plan, which awaits Cabinet approval in October at the earliest.

Even if the plan is approved, it will likely take some time for the government and nuclear plant operators to clear a slew of hurdles, such as estimating the costs of the project and ensuring the safety of shipments.

The Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, which oversees the nuclear industry, is considering outsourcing the disposal of three kinds of large low-level radioactive equipment overseas: steam generators, feed-water heaters and nuclear fuel storing and shipping casks.

These components range in size from 5 to 20 meters and weigh 100 to 300 tons.

Although they are not highly contaminated, compared with nuclear debris generated by spent fuel, they must be disposed of and managed properly, including being buried deep in the ground for years.

The ministry is considering their export as an “exceptional measure” to deal with the grave issue of the radioactive waste accumulating at nuclear facilities across Japan.

“Export regulations will be reviewed to allow for export (of low-level radioactive waste) when certain conditions are met, such as their safe recycling into useful resources,” the draft for the latest version of the Basic Energy Plan said.

The industry ministry is soliciting public opinions on the outsourcing plan until Oct. 4.

Nuclear plant operators have decided to decommission 24 reactors, including the six units at the crippled Fukushima No. 1 nuclear plant.

Work to dismantle those reactors is expected to go into full gear starting in 2025.

Excluding the reactors at the Fukushima plant, the decommissioned units will produce an estimated 165,000 tons of low-level radioactive waste.

But more than 90 percent of that waste has nowhere to go for dismantling and disposal.

Japan still lacks a dedicated disposal site for equipment used at nuclear plants, forcing plant operators to store the waste at their facilities.

The ministry says the storage of the out-of-service equipment is getting in the way of the decommissioning process.

Experts say some businesses in the United States and Sweden clean, melt and recycle metal from radioactive waste sent by foreign countries.

“Japan should first learn the know-how of disposal by outsourcing the work to foreign businesses with a reliable track record in the area and eventually become capable of doing it at home,” said Koji Okamoto, a professor of nuclear engineering at the University of Tokyo.

Under the Joint Convention on the Safety of Spent Fuel Management and on the Safety of Radioactive Waste Management, signatory countries that produce radioactive waste are obliged, in principle, to dispose of it within their territories.

But they can export the waste as exceptional cases if they obtain the consent of countries where business partners are based.

However, Japan’s Foreign Exchange and Foreign Trade Control Law bans such exports.

Utilities have pressed the government for a change in the disposal policy, and the industry ministry has been reviewing the existing setup alongside experts on nuclear technology.

Although the ministry intends to follow the principle of doing away with the waste within Japan, it plans to approve exports of the three types of nuclear plant equipment on condition that they will be recycled.

Ministry officials say the plan can be achieved through a revised ministry directive, without having to change the law.

The equipment intended for recycling overseas could include components kept at nuclear plants that still generate power.

But the ministry needs to work out many issues to turn the plan into reality.

Nuclear plant operators have the primary responsibility for disposing of low-level radioactive waste. And the actual costs these Japanese companies would have to pay to recyclers overseas is still unknown.

The bill could be far more expensive than initially estimated.

How to safely ship the radiation-contaminated equipment abroad is another unresolved issue.

The amount of nuclear waste in Japan has been growing since the 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster. Utilities have gradually resumed operations at nuclear plants, but some have decided to decommission reactors, particularly aging ones, largely because of the costs needed to upgrade them under new safety standards.

For decades, Japan has been unable to secure a final disposal site for such waste inside the country, mainly because of opposition from residents of candidate sites.

TEPCO bungles placement of 100 fire detectors at nuclear plant

September 20, 2021

Tokyo Electric Power Co. has continued its bumbling ways concerning safety measures, misplacing dozens of fire detectors at its Kashiwazaki-Kariwa nuclear plant in Niigata Prefecture, sources said.

TEPCO is seeking to restart the No. 7 reactor at the sprawling nuclear plant, but the utility has run into a host of problems following stricter safety standards implemented after the 2011 disaster at its Fukushima No. 1 nuclear plant.

In the latest incident, about 100 fire detectors were not placed in locations set under safety regulations, the sources said.

The misplacements could delay the detection of heat and smoke from a fire, hampering an immediate response to such a potentially disastrous event.

Under the new safety regulations, nuclear plant operators are required to place a fire detector at least 1.5 meters from an air conditioner vent or other opening. That rule is based on the fire protection law.

Inspectors from the government’s Nuclear Regulation Authority in February noticed that a smoke detector was placed only about 1 meter from the ventilating opening in the storage battery room of the No. 7 reactor building.

TEPCO said it has since moved the detector to the proper location and confirmed through visual checks that the other fire detectors were installed in the right places.

But an additional NRA inspection in April found that two other fire detectors were misplaced.

Following that finding, TEPCO undertook a fresh check of about 2,000 detectors throughout the nuclear plant.

The company reported to the nuclear watchdog on Sept. 16 that more cases of misplaced detectors were confirmed, bringing the total to about 100, according to the sources.

With seven reactors, the Kashiwazaki-Kariwa nuclear plant is among the largest in the world in terms of capacity. It is also the only nuclear facility that TEPCO can restart since the company decided to decommission both the Fukushima No. 1 and No. 2 nuclear plants.

TEPCO is eager to put the Kashiwazaki-Kariwa plant back online because burning fossil fuel at its thermal plants has proved costly.

But the NRA in April ordered the company to stop preparations toward a restart following revelations of a number of safety flaws.

In January, the company announced the completion of work to bolster safeguarding of the No. 7 reactor, which has an output of 1.35 gigawatts.

However, fire-prevention work was not finished at many locations of the nuclear plant.

News outlets also reported in January that an employee of the plant entered the central control room of a reactor by using the ID of another employee in September last year, a serious breach of the NRA’s anti-terrorism measures.

In addition, it was found that security devices designed to detect unauthorized entry had not been working properly at 15 sites at the plant since March last year.

TEPCO left most of these devices unfixed for about a month.

The company is expected to submit a report to the NRA on how to prevent a recurrence by Sept. 23.

New radiation scrubber begins cleaning water at Fukushima plant

New radiation scrubber begins cleaning water at Fukushima plant, Japan Times 19 Sep 21The operator of the crippled Fukushima No. 1 nuclear plant on Thursday powered up an additional water treatment facility to scrub contamination from the massive quantities of radioactive water stored there.

The new, mobile facility filters radioactive strontium from water used to cool three reactors that partially melted down in March 2011, said operator Tokyo Electric Power Co., and can handle 300 tons of water a day……

The procedure will reduce radioactive strontium in the water to about one-thousandth of its current level, the utility said.

However, removing strontium will not in itself render the water safe. It then needs to be treated by another system at the plant which filters out around 60 kinds of radioactive materials.

But there is an important reason why the strontium takes precedence. Removing that isotope before the others will make the water far less of a hazard in the event of a major leak into the ocean.

Meanwhile, an estimated 400 tons of groundwater continues to seep into the reactor basements every day, forcing the utility to find ways to store it. Tepco already has 400,000 tons of toxic water stored at the site, which will all need to be treated one day. https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2014/10/03/national/new-radiation-scrubber-begins-cleaning-water-at-fukushima-plant/

Tepco technicians ignored Fukushima filters leaking radioactive water.

Technicians at Japan’s wrecked Fukushima nuclear power plant have acknowledged neglecting to investigate the cause of faulty exhaust filters key to preventing radioactive pollution, after being forced to replace them twice. Representatives of the Tokyo Electric Power Company made the revelations Monday during a regular review of the Fukushima Daiichi plant at a meeting with Japanese regulatory authorities.

The plant suffered triple meltdowns following a massive earthquake and tsunami in 2011. “At the core of this problem is TEPCO´s attitude,” said a Nuclear RegulationAuthority commissioner, Nobuhiko Ban, at the meeting. TEPCO has been

repeatedly criticized for coverups and delayed disclosures of problems atthe plant. In February, it said two seismometers at one reactor remained broken since last year and failed to collect data during a powerful quake.

Company officials have said that 24 out of 25 filters attached to water treatment equipment had been found damaged last month, after an alarm went off as workers were moving sludge from the unit to a container, temporarilysuspending the water treatment. The operation partially resumed last weekafter filter replacement. The filters are designed to prevent particles from escaping into the air from a contaminated water treatment system – called Advanced Liquid Processing System, or ALPS – that removes selected radioactive isotopes in the water to below legally releasable limits.

Daily Mail 14th Sept 2021

Irradiated man kept alive for nuclear research

Paul Richards, Nuclear Fuel Cycle Watch Australia, 10 Sept 21, TOTAL DESTRUCTION

Although most of Hisashi Ouchi’s body had been completely destroyed, including his DNA and immune system, the doctors kept him alive as a human experiment.They kept him alive for a total of 83 days until he died of multiple organ failures.

During those 83 days, Hisashi Ouchi underwent the first transfusion of peripheral stem cells, as well as several blood transfusions and skin transplants.However, neither the transfusions or transplants could keep his bodily fluids from leaking out of his pores.

During the first week of experiments, Hisashi Ouchi had enough consciousness to tell the doctors“I can’t take it anymore… I am not a guinea pig…”but they continued to treat him for 11 more weeks. The nurses caring for him also recorded the narcotic load to abate pain was not enough to give him relief. At the time of recording his death, his heart had stopped for 70 minutes and the doctors chose this time not to resurrect him.

UNBREAKABLE RECORD To this day, Hisashi Ouchi holds the record for the most radiation experienced by a surviving person, however, this is not an accomplishment that his family likely celebrates.

The case of malpractice by these doctors is extremely horrific and one of the greatest examples of human torture of the 20th century.Thankfully, medical professionals values, would not be superseded by the nuclear state, so this record in all probability will never be broken._____________More on why the accident happened:https://sci-hub.se/…/abs/10.1080/00963402.2000.11456942 from https://www.facebook.com/groups/1021186047913052

Energy Markets Bet Against Nuclear As Election Nears In Japan

Energy Markets Bet Against Nuclear As Election Nears In Japan, Oil Price, By Haley Zaremba – Sep 08, 2021 Japanese Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga shocked the world on Friday when he announced that he will be stepping down and declining to seek re-election after serving one term. ………

one candidate has emerged as a major frontrunner. ….. Taro Kono served as the minister in charge of battling Covid-19 in Japan. It is looking likely that Kono will garner the support of the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP), whose majority in the Japanese parliament ensures that any candidate who heads the party will ultimately win the race for Prime Minister. Kono emerged as the clear frontrunner in Japanese media polls over the weekend that asked respondents to indicate their preferred leader.

It remains to be seen whether Taro Kono will take the helm of Japan, but if he sticks to his guns, the Japanese nuclear energy sector could soon recede into the rearview.

In addition to being known for his role in combating the novel coronavirus pandemic, Kono is also a noted anti-nuclear advocate with a long history of outspoken dissent about the nuclear energy that currently represents a fifth of Japan’s energy mix. Due to this history, the news of Kono’s ascent toward the Prime Minister position on Monday has already sent shockwaves through Japan’s energy markets.

So far, renewable energy markets are winning big. “Frenzied buying from retail traders sent Japan’s renewable energy stocks soaring Monday,” in response to Kono’s emergence as a top contender according to reporting from Bloomberg. Solar and biomass power company Renova Inc. saw its stock increase by 15% while solar firm West Holdings Co. hit an all-time high after its stocks jumped 9%. These gains came at a cost to nuclear energy firms and power companies, and Kansai Electric Power Co. stocks notably dropped 2.7%.

Although the markets have already spoken, it remains to be seen whether Kono will stick to his staunchly anti-nuclear stance if he enters office as Prime Minister. “Whether he will actually reflect his previous stance into his policies once the race for the prime minister position begins is a different story,” Norihiro Fujito, chief investment strategist at Tokyo’s Mitsubishi UFJ Morgan Stanley Securities Co. was quoted by Bloomberg. “The market is just getting ahead of itself.”

…….. Currently, the national plan “calls for renewable sources to provide between 22% and 24% of Japan’s electricity by 2030, and for nuclear energy to provide between 20% and 22%.” But nuclear energy is a hard sell in Japan, a country that is still recovering from the devastating 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster

Just this week, a full decade after the tragedy caused by an earthquake and ensuing tsunami, the International Atomic Energy Agency is reaching out to Japan to work alongside them in their continuing struggles to manage the radioactive waste still piling up after the 2011 accident. Japan has continued to use more than a million tonnes of water to cool the damaged reactors and prevent a meltdown, and now they’re running out of storage space for the radioactive waste water. Their plan? Dump it into the Pacific Ocean.

The continued complications and hazardous aftereffects of the nuclear disaster at Fukushima throw the dark side of nuclear into stark relief for the Japanese public. ……… It remains to be seen whether Taro Kono will take the helm of Japan, but if he sticks to his guns, the Japanese nuclear energy sector could soon recede into the rearview. https://oilprice.com/Alternative-Energy/Nuclear-Power/Energy-Markets-Bet-Against-Nuclear-As-Election-Nears-In-Japan.html

IAEA Seeks Japan Transparency in Release of Fukushima Water

IAEA Seeks Japan Transparency in Release of Fukushima Water, By Mari Yamaguchi | September 8, 2021 TOKYO (AP) — Experts from the International Atomic Energy Agency asked Japan on Tuesday for full and detailed information about a plan to release treated but still radioactive water from the wrecked Fukushima nuclear plant into the ocean.

The three-member team, which is assisting Japan with the planned release, met Tuesday with government officials to discuss technical details before traveling to the Fukushima Daiichi plant for an on-site examination Wednesday. They will meet with Japanese experts through Friday…….. https://www.claimsjournal.com/news/international/2021

Japan’s Liberal Democratic Party hopes that presidential contender Taro Kono will drop his anti nuclear stance.

LDP leadership race hopeful Taro Kono modifies stance on nuclear energy Japan Times 8 Sept 21, Liberal Democratic Party leadership race hopeful Taro Kono indicated his readiness on Wednesday to accept the restart of idled nuclear power plants for the time being, in order for Japan to realize its goal of achieving carbon neutrality by 2050.

“It’s necessary to some extent to restart nuclear plants that are confirmed to be safe, as we aim for carbon neutrality,” Kono, currently regulatory reform minister, told reporters.

Kono, known as an advocate for a shift away from nuclear energy, is eager to run in the ruling party’s leadership election on Sept. 29 to select a successor to outgoing LDP President and Prime Minister Yoshihide .

However, there are concerns among some LDP members over his position on the issue. Kono apparently modified his stance to win broader support ahead of the party election.

“Basically, our priority is to increase the use of renewable energy sources, but it would be possible to use nuclear plants whose safety is confirmed for now if there are power supply shortages,” Kono said.

“Nuclear plants will disappear eventually, but I’m not saying that they should be scrapped immediately, like tomorrow or next year,” he added.

With Kono also in charge of COVID-19 vaccine rollout, some people are questioning whether it would be possible for him to continue in the role while campaigning for the LDP presidency.

“I don’t think (my election campaign) would affect my duties,” Kono said….. https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2021/09/08/national/politics-diplomacy/kono-nuclear/

Nuclear ”ethics” – fatally ill man kept alive against his will, in the cause of nuclear research

In 1999 an accident at a Japanese Nuclear Power Plant caused one of its technicians, Hisashi Ouchi, to be exposed to high levels of radiation. He was kept alive for 83 days, against his will, by doctors so they could use his body to study the effects of radiation on humans.Hisashi Ouchi was one of three employees of the Tokaimura nuclear plant to be heavily impacted by the accident on 30 September 1999.

The Man Kept Alive Against His Will

How modern medicine kept a ‘husk’ of a man alive for 83 days against his will

https://historyofyesterday.com/the-man-kept-alive-againsthttps://historyofyesterday.com/the-man-kept-alive-against-his-will-647c7a24784 Colin Aneculaese 27 July 2020, Radiation has always been a subject of great interest for many scientists. Since its discovery and weaponisation, many have looked into its impact on living organisms, especially humans. As a result, many living being suffered at the hands of those who sought to find the real impact of radiation on living beings. Throughout the years this experimentation was mainly focused on animals as it would be unethical to test such a thing on humans.

Outside of major nuclear events such as the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the meltdowns of nuclear facilities such as nuclear power plants, the effect of radiation on humans could not be tested. As such after the 1999 Tokaimura nuclear accident, many scientists jumped at the opportunity to study the victims of such a high amount of explosion to radiation. Out of all the victims of the disaster, the case of Hisashi Ouchi stands out.

Tokaimura nuclear plant

Hisashi Ouchi was one of three employees of the Tokaimura nuclear plant to be heavily impacted by the accident on 30 September 1999. Leading up to the 30th of the month the staff at the Tokaimura nuclear plant were in charge of looking after the process of dissolving and mixing enriched uranium oxide with nitric acid to produce uranyl nitrate, a product which the bosses of the nuclear plant wanted to have ready by the 28th.

Due to the tight time constraints, the uranyl nitrate wasn’t prepared properly by the staff with many shortcuts being used to achieve the tight deadline. One of these shortcuts was to handle the highly radioactive produce by hand. During their handling of the radioactive produce while trying to convert it into nuclear fuel (uranyl nitrate is used as nuclear fuel) for transportation the inexperienced three-man crew handling the operation made a mistake.

During the mixing process, a specific compound had to be added to the mixture, the inexperienced technicians added seven times the recommended amount of the compound to the mixture leading to an uncontrollable chain reaction being started in the solution. As soon as the Gamma radiation alarms sounded the three technicians knew they made a mistake. All three were exposed to deadly levels of radiation, more specifically Ouchi receiving 17 Sv of radiation due to his proximity to the reaction, Shinohara 10 Sv and Yokokawa 3 Sv due to his placement at a desk several meters away from the accidents. When being exposed to radiation it is said that anything over 10 Sv is deadly, this would prove to be true in this instance.

The fallout of radiation

Shinohara, the least affected out of the two who received a deadly dose of radiation, lasted 7 months in hospital until 27 April 2000. The technician died of lung and liver failure after a long battle against the effects of the radiation he endured. During his, 7-month stay at the University of Tokyo Hospital several skin grafts, blood transfusions and cancer treatments were performed on him with minimal success. Shinohara’s time at the University of Tokyo Hospital would be much less painful than Ouchi’s.

Protests as France sends latest shipment of used nuclear fuel to Japan

Protests as France sends latest nuclear shipment to Japan https://www.france24.com/en/live-news/20210908-protests-as-france-sends-latest-nuclear-shipment-to-japanActivists from environmental group Greenpeace protested against a shipment of reprocessed nuclear fuel that was set to leave France for Japan on Wednesday for use in a power plant.

The load of highly radioactive Mox, a mixture of reprocessed plutonium and uranium, was escorted by police from a plant near the port of Cherbourg to the dockyard in the early hours of the morning.

A handful of Greenpeace activists waved flags and signs with anti-nuclear logos as they camped out on Tuesday night to wait for the heavy-goods truck transporting the high-security cargo.The Mox from French nuclear technology group Orano is destined for a nuclear plant in Takahama in Japan and is the seventh such shipment from France since 1999.

Japan lacks facilities to process waste from its own nuclear reactors and sends most of it overseas, particularly to France.

The country is building a long-delayed reprocessing plant in Aomori in northern Japan.

“Orano and its partners have a longstanding experience in the transport of nuclear materials between Europe and Japan, in line with international regulations with the best safety and security records,” Orano said in a September 3 statement.

The fuel is being shipped by two specially designed ships from British company PNTL.

Media Coverage of Fukushima, Ten Years Later.

Abstract: When taking up the unlearned lessons of Fukushima, one of the biggest may have been the need for more robust oversight of the nuclear industry. In Japan, the failure of the major national news media to scrutinize the industry and hold it accountable was particularly glaring. Despite their own claims to serve as watchdogs on officialdom, the major media have instead covered Japan’s powerful nuclear industry with a mix of silent complicity and outright boosterism. This is true both before and after the Fukushima disaster. In the decades after World War II, when the nuclear industry was established, media played an active role in overcoming public resistance to atomic energy and winning at least passive acceptance of it as a science-based means for Japan to secure energy autonomy.

During the Fukushima disaster, the media served government objectives such as preservation of social order by playing down the size of the accident and severity of radiological releases, resulting in widely divergent coverage from serious overseas media. While a short-lived proliferation of more critical and independent coverage followed the disaster, the old patterns returned with a vengeance after the installment of the pro-nuclear administration of Abe Shinzō. This article will examine the roots of the Japanese media’s failure to challenge or scrutinize the nuclear industry, and how this complicity has played out in the post-Fukushima era. It will use a historical analysis to look at how the current patterns of media coverage were actually established in the immediate postwar period, and the formation of public support for civilian nuclear power.

During my 15 years as a foreign correspondent in Tokyo, including a six-year stint as Tokyo bureau chief of The New York Times (2009-2015), I often covered the same news events as Japanese journalists, standing shoulder-to-shoulder at more press conferences than we’d care to count. While I admire many Japanese colleagues individually as journalists, I was frequently struck by the shortcomings of Japan’s big domestic media and Japanese journalism as an institution.

But never did I feel these structural weaknesses as keenly as I did in the tense weeks that followed the triple meltdown at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station.

In Minami-soma, a city 25 kilometers north of the stricken plant, where some 20,000 remaining residents were cut off from supplies of food, fuel and medicines, I discovered that journalists from major Japanese media were nowhere to be seen. They had withdrawn from Minami-soma, forbidden by their editors in Tokyo from approaching within 30 or 40 kilometers of Fukushima Daiichi.

By doing so, they had essentially abandoned the already isolated residents. But you would never know that from the media’s stories, which made no mention of their own pull out or the perceived risks that had prompted this retreat. Instead, the main newspaper articles uniformly repeated official reassurances that there was no cause for alarm because the radiation posed “no immediate danger to human health,” as the chief cabinet secretary at the time, Edano Yukio, so famously put it.1

The mismatch between word and deed—between what the newspapers were telling their audiences and what they were actually doing to protect their own journalists—was glaring. It turned out that this was only the first of several instances during the Fukushima disaster where I witnessed Japan’s major media adhering to the official narrative regardless of the facts on the ground. I refer to this phenomenon as “media capture,” borrowing from the more widely used term “regulatory capture,” which is used to describe a similar failure of government oversight of the nuclear industry.

Over the months and years that followed the meltdowns, I saw numerous instances of national media refusing to take a critical or distanced stance in their coverage of the nuclear industry and its government regulators. Instead, they repeatedly chose to internalize the official narratives and even adhere to the government-approved language. We saw this is the widely diverging narratives that started appearing in the serious foreign press versus the major domestic media as the accident worsened.

To cite a straightforward example, we started using the word “meltdown” within hours of the first reactor building explosion at the plant, reflecting the almost unanimous view of outside experts that a melting fuel core was the only realistic source of the hydrogen that caused the blast. However, the domestic national dailies and NHK avoided the word “meltdown” (in Japanese, merutodaun) for months, following the insistence of the Ministry of Economics, Trade and Industry (METI), the powerful government agency that both promoted and regulated Japan’s nuclear industry, that a meltdown had not been confirmed. The big Japanese media used other official euphemisms as well, including “explosion-like event” to describe the massive blast at the Unit 3 reactor building, which blew chunks of concrete hundreds of feet into the air.

In fact, I even had Japanese journalists calling me to berate me and my newspaper for using the M-word without METI’s permission. Readers of the Japanese national dailies didn’t see the M-word until mid-May, when METI and the plant’s operator, Tokyo Electric Power Co. or TEPCO, conceded in public that Fukushima Daiichi had indeed suffered a meltdown in mid-March—three meltdowns, in fact.

In the chapter that I wrote for Legacies of Fukushima: 3.11 in Context, I tried to explain some of the reasons why the civilian nuclear power industry could have such a peculiarly strong grip on the media and their narratives. The nuclear industry was a national project that was promoted by the powerful central ministries as a silver bullet for resource-poor Japan’s dependence on imported energy. This gave it an elevated status as the elite bureaucrats guided Japan’s postwar recovery and economic take-off.

I looked at the media’s dependence on Tokyo’s powerful central ministries, which takes its most visible form in the so-called kisha kurabu, or “press clubs.” These are arrangements that allow national media to station their journalists inside the ministries and agencies, where they are given their own room and exclusive access to officials. Much of the reporting by the major Japanese media starts in the kisha kurabu, where journalists gather to wait for the next press conference or off-record briefing from officials. The kisha kurabu system fosters a passive form of journalism, in which reporters become dependent on the ministry within which they are embedded. In pursuit of a scoop that can make or break a career, the journalists compete for handouts from ministry officials. All too often, they enter a Faustian bargain in which the journalists swap narrative control in exchange for exclusive access to information. The result is a passive form of access journalism that ends up repeating spoon-fed official narratives.

I also looked to the past at the emergence of newspapers like the Asahi Shimbun during the early to mid-Meiji era, when the national priority was to protect autonomy by finding a way to catch the industrialized West. I argued that this history baked into the mindset of Japanese journalists a feeling of responsibility for the fate of their nation, including its vital energy needs. It also led to an identification with the government, and particularly the elite officialdom, as protectors of Japan and its people from predatory foreign powers. This inclination to side with the state has continued in the postwar period, when journalists have clearly seen themselves as members of a national elite attached to a broader bureaucratic-led system.

One point that I wanted to underscore was that this media capture was not something so simple or venal as corruption. This is how it is often portrayed by critical Japanese writers, usually freelancers and book authors, who focus on the so-called Nuclear Village, a nexus of business, government, labor unions, academia and news media linked by the cash flowing out of the highly profitable nuclear plants. While money doubtlessly plays a role in many of these relationships, including perhaps the for-profit commercial TV broadcasters, I see no direct evidence that it sways the coverage of the national newspapers. These are privately held companies for whom advertising is a much less important revenue source than subscriptions (or the rent from their valuable real estate holdings in central Tokyo and Osaka).

Regardless of the cause, the result has been generations of postwar journalists who have consistently failed to serve as watchdogs on one of the nation’s most politically powerful industries.2 Starting in the 1990s, public scandals started plaguing the industry, and TEPCO in particular. In 2002, government inspectors announced that TEPCO had been routinely falsifying safety reports to hide minor incidents and equipment problems at reactors including several at Fukushima Daiichi. TEPCO eventually admitted to more than 200 such violations stretching back to 1977. Five years later, TEPCO revealed even more cover-ups of safety issues, which the company had failed to report in the previous inquiry.

Despite what was clearly a chronic and systemic failure of both internal compliance and government oversight, no one was arrested or charged, and the existing regulatory framework left unchanged. The media could have played a role of holding the regulators’ feet to the fire by exposing the structural problems behind this abysmal record of obfuscation and cover-ups. Instead, the watchdogs chose to remain largely silent, reporting on the government’s revelations, but making few efforts at independent investigative reporting.

Of course, such criticisms enjoy the benefits of hindsight, with the accident in 2011 making it easier to see these failures as part of a broader narrative that leads inevitably to Fukushima. But how about after 2011, when the severity of the disaster led to numerous calls for reform? During that time, the national media have also been held up to uncomfortable scrutiny by a jaded and distrustful public, who felt betrayed by their early coverage of the accident.

Unfortunately, ten years later, nothing seems to have changed.

This was apparent in mid-April of 2021, when the Japanese government announced a decision to release into the Pacific Ocean more than 1.2 million tons of radioactive water that has been building up in hundreds of huge metal tanks on the grounds of the Fukushima Daiichi plant. (The accumulation of contaminated water has plagued the plant from the early days of the disaster. TEPCO has resorted to some high-tech solutions with mixed results, including a mile-long “ice wall” of frozen dirt that failed to fully block the water, much of which flows into the plant from underground.)

The water stored in these tanks contains tritium, a radioactive isotope of hydrogen that is best known for its military use as the fuel for thermonuclear warheads (hence the term “hydrogen bomb”). On the spectrum of radioactive substances, tritium emits relatively low levels of radiation in form of beta particles. But it is a radioactive substance nonetheless, a fact that major media played down or even omitted by choosing, once again, to adopt the industry and government’s language to describe the dump. The main news stories in the major national newspapers and TV broadcasts used the official term for this water, which is shorisui, or “treated water.”

While technically correct, this term euphemistically glosses over the fact that this is not the same as, say, treated sewage water. Nor does treated water convey the fact that this water still contains a radionuclide that emits beta radiation.

One result was an interesting battle of words that pitted the mainstream media, which used the approved “treated water,” against journalists who were outside the press club’s inner circle. These publications and web sites chose to use clearer terms such as osensui, or “contaminated water.” The leftist daily Tokyo Shimbun, a smaller regional newspaper that has stood out for its more critical coverage of the nuclear disaster, compromised by calling the water osenshorisui, or “contaminated treated water.”3

More eye-opening was the fact that there were actually efforts to enforce use of the officially approved term. As many journalists discovered, there was an army of social media trolls at ready to pile onto anyone with the temerity to use more critical terminology, and particularly “contaminated water.” TEPCO and the government mobilized university experts and PR professionals to police the public sphere for use of words that were deemed “unscientific” and “ideological.”

Of course, the choice of the word “treated” is itself also highly political. It buttressed the larger message put forth by the government and the plant’s operator that the release of this water was no cause for alarm, but something very common and normal that nuclear plants around the world do all the time. By accepting the official terminology, the media were implicitly adopting this framing of the issue, which focused on the claim that the water could be diluted to the point of being harmless when dumped into the Pacific.

Scientifically, this is a valid claim. My point here is not to take sides. Rather, I am criticizing the large domestic media for failing to do the same: i.e., not take sides. By adopting the official narrative, the media were complicit in the government’s and TEPCO’s exclusion of other, also valid counterarguments. One of the biggest is the fact that this release is anything but normal. No nuclear plant has ever conducted an orchestrated release of such a huge quantity of tritium-laden water. (At the time of writing, the amount, 1.2 million tons, is enough to fill almost 500 Olympic-sized swimming pools.) Worse, the release is to be carried out in the same closed, opaque manner as the rest of Japan’s decade-long response to the disaster. Unless TEPCO and METI break with past precedent to allow full international oversight to verify that the water is as clean as they claim it is, we are left once again to trust actors who have consistently violated public faith.

Just as importantly, there are valid reasons to at least question whether the water is as clean as TEPCO says it is. The company has been telling us for years that it has installed state-of-the-art treatment and filtration technologies that scrub the water of every radioactive particle except tritium. However, in 2018, the plant operator suddenly revealed that 75% of the treated water at the plant still contained excessive amounts of other, more radioactive substances including strontium 90, a dangerous isotope that can embed itself in the living tissue of human bones.4

To be fair, TEPCO may be right in its assessment of the water’s safety. Even so, it is the job of conscientious journalists to take a skeptical attitude toward such claims until they can be independently verified. The media also need to remind why this is necessary, given the company’s and the industry’s history of cover-ups. My goal here is to fault the major domestic media for once again failing to do this, despite the bitter lessons of 2011. Adopting the language of METI and TEPCO privileges the official perspective over others. It shows that the journalists are internalizing the official framing of the event and how it should be discussed and understood.

Officialdom is thus allowed to set the boundaries of public debate, excluding more critical perspectives as “political,” “unscientific” or even “foreign.” The last characterization reflects the fact that the Chinese and South Korean governments raised some of the loudest objections to the release. The media have tended to frame these as the latest in a litany of self-serving complaints by Asian rivals that like to accuse Japan of failing to apologize for World War II-era atrocities. While Beijing and Seoul may have political motives for seizing on the water issue, this shouldn’t be a reason for journalists to avoid taking up more substantive criticisms about the release. Opposition has appeared in many other countries and reflects the failure of Japan to consult with other nations that share the Pacific Ocean, which will be the site of the mass water dump.

This is a failure by media, once again, to inform their readers of the existence of alternative narratives that take a dimmer view of the actions taken by Japan’s officialdom, or that point out where government interests diverge from those of Japan’s public. This is also a failure of a different sort: of media to protect their own intellectual independence. By uncritically adopting the official narratives, the journalists are relinquishing the right to frame in their issues. This surrendering of agency is the central fact of the media capture that I described above.

To be clear, Japan is not unique in suffering from the problem of media capture. The press in other democratic countries face similar challenges. In the United States, we use the term “access journalism” to describe the pitfalls of journalists, often in Washington, who trade autonomy for exclusive access to official sources. However, Japan’s version of access journalism is more extreme, producing a uniformly monolithic coverage closer to that in non-democratic societies. The most apt American equivalent may be the period of extreme patriotic fervor between the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks and the March 2003 invasion of Iraq, when U.S. media failed to adequately challenge the erroneous claims of the Bush administration that Iraq was in possession of weapons of mass destruction.

In Japan’s ongoing Fukushima disaster, this lack of agency manifests itself as a failure to not only set the narrative, but even to decide what is newsworthy. Most of the coverage is essentially an act of regurgitating the information that was distributed at the ministry’s kisha kurabu. Since the news reports are based on information received from ministry officials, not surprisingly they usually showcase the actions of those officials. Both the pages of Japan’s national dailies and the evening news broadcasts of NHK are filled with stories of Japanese officialdom in action, solving some problem or punishing some wrongdoer. Most news reports are mini-dramas in which officials play the starring role. As such, they serve as demonstrations that agency lies in the elite bureaucracies at the center of the postwar Japanese state, and not the major media, which seems to serve as an appendage.

Even when critical stories appear, they are rarely the work of enterprising reporters unearthing facts that the powerful would rather keep covered. Rather, the revelations tend to come from official actors when they have decided to take action against malfeasance. One example was TEPCO’s cover-ups, mentioned earlier, which were exposed by nuclear regulators, not investigative reporters. A more recent example is revelations that started to become public in March 2021 of years of security lapses at the huge Kashiwazaki-Kariwa nuclear plant in Niigata, facing the Sea of Japan. Over the next two months, news stories dribbled out about workers who were able to access the sensitive areas around the plant’s nuclear reactors without proper ID. In one case in 2015, a man entered the reactor area using the ID of his father, who also worked at the plant. Once again, there lapses were not exposed by intrepid reporters but regulators themselves, who leaked them to prepare the public for their decision to reject TEPCO’s request to restart the plant.5

The lack of media agency is all the more glaring because there have been very notable exceptions. Japan’s journalists have shown that they are capable of true investigative reporting that can define and drive the public narrative. For a brief window of time during the early years of the Fukushima disaster, some major Japanese media experimented with more autonomous journalism. This began in the late summer of 2011, as public disillusionment in the domestic press’s compliant coverage grew. This prompted some media to try to re-engage readers with more hard-hitting reports that challenged the official claims.

The most notable of these efforts was launched by the Asahi Shimbun, Japan’s second-largest daily, which beefed up a new reporting group dedicated to investigative journalism. (By investigative journalism, I mean journalists taking the initiative to pry out hidden truths and assemble these into original, factual narratives that challenge the versions of reality put forth by the powerful.) The Asahi’s investigative division got off to a strong start by winning Japan’s most prestigious press award two years in a row. It scored what it trumpeted as its biggest coup in May 2014, when two of its reporters wrote a front-page story that exposed the dangerously poor crisis management at the plant as it teetered on the brink of catastrophe. The story revealed that the government had hidden testimony by the Fukushima Daiichi plant’s manager during the accident, Yoshida Masao, who later died of cancer. It also recounted what it said was the most explosive revelation of this secret testimony: that hundreds of workers and staff had fled the crippled plant at the most dangerous point in the disaster, despite the fact that Yoshida never gave them the order to leave.

However, the Asahi erred by giving the story a misleading headline, which left readers with the impression that the workers had fled in defiance of Yoshida’s order to stay. (In fact, Yoshida himself says in the testimony that his order didn’t reach these workers—a stunning breakdown in command and control that was lost in the subsequent blow up over the article.) This misstep gave critics the opening that they needed to try to discredit the entire story, and by extension the newspaper’s proactive coverage of the disaster. A host of critics, including the prime minister himself and the rest of the mainstream media, set upon the Asahi with unusual ferocity. After weeks of withering attacks, which essentially accused the newspaper of lacking patriotism and of belittling the heroic plant workers, the Asahi’s president made a dramatic surrender in September 2014, retracting the entire article, gutting the investigative team and resigning his own job to take responsibility for the fiasco.6

Thus marked the end of the Asahi’s short-lived foray into investigative journalism, which I have described in more detail in this journal.7 Suffice it to say here that when forced to make a choice, the Asahi, the nation’s leading liberal voice favored by the intelligentsia, chose to remain on the boat. To preserve the privileged insider status as a member of the kisha kurabu media, the newspaper chose to sacrifice not only its biggest reporting accomplishment of the disaster, but also the journalists who produced it, who were sent into humiliating internal exile. For years afterward, the newspaper shunned proactive reporting on Fukushima, staying within safe confines of the official storyline.

The Asahi’s biggest mistake was its failure to stand behind its journalists. Investigative reporting is by nature a highly risky undertaking, and one that pits a handful of underpaid journalists against some of the most powerful members of society. By not only failing to stand up for its investigative reporters but trying to scapegoat them by punishing them for the mistakes in coverage, the Asahi sent a chilling message to all mainstream journalists: Newspapers don’t have your back. In such an environment, what journalists in their right mind would want to challenge the powers that be?

Admirably, some of the Asahi’s investigative reporters did stand their ground even at the cost of their careers at the newspaper. Soon after the debacle, two of the investigative group’s top reporters quit to launch Japan’s first NGO dedicated to investigative journalism, which in 2021 was renamed Tokyo Investigative Newsroom Tansa.8 Another resigned to join Facta, a Japanese magazine dedicated to investigative coverage (and offering stories that cannot be found in the large national newspapers). These decisions to place principle over company and career underscore my broader point: The sources of Japan’s media capture are bigger than the individual reporters and embedded in the structure of media institutions and the practice in Japan of journalism itself.

The Asahi’s capitulation in 2014 marked the end of not just the Asahi’s but all the mainstream media’s efforts to create new, more critical narratives of the Fukushima disaster. These days, most reporting tends to fall into one of a few prepackaged, safely uncontroversial storylines. There is the Fukushima 50 narrative of successfully overcoming Japan’s biggest trial since World War II. Another is the “baseless rumors” (fuhyō higai) narrative, which casts fears of radiation as over-exaggerated, and usually the creation of women, leftists and foreigners.

Journalists have told me that the Asahi’s surrender created a powerful prohibition on critical coverage. Having seen what happened to Japan’s leading liberal newspaper, and the star reporters there who lost their careers, few journalists have the stomach to challenge the status quo. The result is a grim new conformity.

Adding to the pressure to toe the line has been the appearance post-Fukushima of another new, problem-plagued national project: the Tokyo Summer Olympics, originally scheduled for 2020. Coverage of the Olympics has again tended to adhere to official narratives, even as public misgivings grew in Prime Minister Suga Yoshihide’s decision to go forward with the Games a year later, in 2021, in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic.

From the start, the government has used the Olympics to divert attention from Fukushima while proclaiming that the disaster is now in the past. While there has been critical coverage, it has been the exception and not the rule. Indeed, the media’s silence was deafening when the previous prime minister, Abe Shinzō, told the International Olympic Committee in Buenos Aires in September 2013 that the plant’s “situation was under control,” even as contaminated water was then still bleeding into the Pacific.

By failing to take the initiative in Fukushima, the media have ended up supporting official efforts to use the Games to put the lid back on the nuclear disaster. The Olympics have become yet one more means for Japan’s elites to regain control of the public sphere, or at least the part of it controlled by the big legacy media. (They have had less success asserting control over the much more anarchic and anonymous world of social media.)

The media’s reluctance to challenge the government has also been apparent during the Covid-19 pandemic. I’m still waiting for the investigative articles that expose the truth behind Tokyo’s biggest failures during the pandemic. The major media emitted barely a peep in response to the government’s blatantly discriminatory decision during the first six months of the pandemic to close Japan’s borders to all foreign nationals, including long-term residents, while allowing Japanese nationals to come and go. More importantly, I would be the first in line to read an investigative exposé into what delayed the roll out of vaccines in Japan.

All too often, coverage of COVID-19 ended up repeating the pattern that we saw in Fukushima. The media once again surrendered their biggest public asset: their power to challenge the official narrative and expose the facts that officials don’t want us to know. Instead, the major domestic media once again show themselves more interested in preserving their privileged insider status. By doing so, they once again do a disservice of their readers.

The need to serve their readers by finding an independent and critical voice should have been the media’s biggest takeaway from Fukushima. Instead, they appear to be merely repeating the mistakes of a decade ago.

References

Brown, A. and Darby, I. (2021) ‘Plan to discharge Fukushima plant water into sea sets a dangerous precedent’, The Japan Times, April 25 [Online]. Accessed: June 25, 2021.

Fackler, M. (2016) ‘Sinking a bold foray into watchdog journalism in Japan’, Columbia Journalism Review [Online]. Accessed: June 25, 2021.

Fackler, M. (2016) ‘The Asahi Shimbun’s failed foray into watchdog journalism’, The Asia Pacific Journal Japan Focus, 14(24) [Online]. Accessed: June 25, 2021.

Jomaru, Y. (2012) Genpatsu to media shinbun jānarizumu ni dome no haiboku [Nuclear Power and the Media: The Second Defeat of Newspaper Journalism]. Tokyo: Asahi Shimbun Shuppan.

Kyodo. (2021) ‘Another security breach at Tepco nuclear plant uncovered’, The Japan Times, May 9 [Online]. Accessed: June 25, 2021.

Ogawa, S. (2021) ‘Fukushima dai ichi genpatsu no osen shorisui, seifu ga kaiyō hōshutsu no hōshin o kettei e 1 3 nichi ni mo kanei kakuryō kaigi [Government Moving Toward Decision to Release the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Plant’s Contaminated Treated Water in the Ocean], Tokyo Shimbun, April 9 [Online]. Accessed: June 25, 2021.

Tansa. (2021) Tokyo investigative newsroom Tansa [Online]. Accessed: June 4, 2021.

Notes

SankeiNews (2011). “Edano kanbōchō kankaiken No1 ‘Tadachi ni kenkō shigai wa denai…’” [Chief Cabinet Secretary Press Conference Edano No1 ‘No Immediate Health Damage’]) [Online Video]. Accessed: August 23, 2011.2

Jomaru, 2012.3

Ogawa, 2021.4

Brown and Darby, 2021.5

Kyodo, 2021.6

Fackler, 2016.7

Fackler, 2016.8

Tansa, 2021.

-

Archives

- January 2026 (259)

- December 2025 (358)

- November 2025 (359)

- October 2025 (376)

- September 2025 (258)

- August 2025 (319)

- July 2025 (230)

- June 2025 (348)

- May 2025 (261)

- April 2025 (305)

- March 2025 (319)

- February 2025 (234)

-

Categories

- 1

- 1 NUCLEAR ISSUES

- business and costs

- climate change

- culture and arts

- ENERGY

- environment

- health

- history

- indigenous issues

- Legal

- marketing of nuclear

- media

- opposition to nuclear

- PERSONAL STORIES

- politics

- politics international

- Religion and ethics

- safety

- secrets,lies and civil liberties

- spinbuster

- technology

- Uranium

- wastes

- weapons and war

- Women

- 2 WORLD

- ACTION

- AFRICA

- Atrocities

- AUSTRALIA

- Christina's notes

- Christina's themes

- culture and arts

- Events

- Fuk 2022

- Fuk 2023

- Fukushima 2017

- Fukushima 2018

- fukushima 2019

- Fukushima 2020

- Fukushima 2021

- general

- global warming

- Humour (God we need it)

- Nuclear

- RARE EARTHS

- Reference

- resources – print

- Resources -audiovicual

- Weekly Newsletter

- World

- World Nuclear

- YouTube

-

RSS

Entries RSS

Comments RSS