Seventy years on, Indigenous victims of UK’s nuclear tests in South Australia still await justice

Rudi Maxwell Oct 14 2023 https://thenewdaily.com.au/news/indigenous-news/2023/10/14/indigenous-victims-sa-nuke-tests/

Seventy years ago Yami Lester was playing outside with his friends at Wallatinna Station in remote South Australia when the ground shook beneath their little feet.

Then a strange black mist quietly rolled in.

On that day, October 15, 1953, the British government conducted its first nuclear test on the Australian mainland, at Emu Field, 170km from Wallatinna.

Mr Lester, a Yankunytjatjara man, was blinded by the fallout.

Before he died in 2017, he shared his memories of the explosion with ICAN, the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear weapons.

“It wasn’t long after that a black smoke came through, a strange black smoke, it was shiny and oily,” he said.

“A few hours later we all got crook, every one of us.

“We were all vomiting; we had diarrhoea, skin rashes and sore eyes. I had really sore eyes, they were so sore I couldn’t open them for two or three weeks.

“Some of the older people, they died.”

Between 1952 and 1963, the British government, with the active participation of the Australian government, conducted 12 major nuclear test explosions and up to 600 ‘minor’ trials in remote South Australia and off the coast of Western Australia.

The ‘minor trials’ dispersed 24.4 kg of plutonium in 50,000 fragments, 101kg of beryllium and 8 tonnes of uranium.

Radioactive contamination from the tests was detected across much of the continent. For decades the authorities denied, ignored and covered up the consequences.

Legacy of trauma

Australia held a royal commission into the tests, which handed down its final report in 1985. In the UK, former service personnel are still fighting with the government for access to records.

Karina Lester says little was done to protect Aboriginal communities during nuclear tests, the ones at Emu Field were known as Totem 1 and Totem 2.

Little was done to protect the 16,000-or-so test-site workers, and even less to protect nearby Aboriginal communities, as Karina Lester, Yami’s daughter, explained.

“The country is still wearing the scars and the people are still wearing those scars as well,” Ms Lester told AAP.

“One of the things I’ve been concerned about as a second generation survivor is that there has been no clean-up at Emu Field in 70 years, so we still don’t know if it’s safe for us to hunt and gather and collect food on or to even visit.

“And so it’s a difficult time for the family but also a time for us to remember and remind our fellow Australians of exactly what happened 70 years ago at Totem 1 and Totem 2 at Emu Field.”

Reconciling With Truth Requires Listening… what about nuclear waste?

September 30, 2023 https://mailchi.mp/preventcancernow/reconciling-with-truth-requires-listening?e=ba8ce79145 #nuclear #antinuclear #nuclear-free #NoNukes

As Canadians look back and Remember the Children who suffered at residential schools, we wish to highlight Algonquin First Nations’ important work to protect the health of children, and the Kitchi Sibi (Ottawa) River watershed from pollution.

The First Nations oppose a hillside nuclear waste Near-Surface Disposal Facility (NSDF) proposed on unceded Algonquin territory at the Chalk River Nuclear Laboratories. In a remarkable turn of events, rainfall during the final hearing on the NSDF demonstrated that the Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission (CNSC) is unlikely to meet its goal to keep nuclear waste secure for hundreds of years.

At Chalk River Nuclear Laboratories scientists first worked on the atomic bomb in the 1940s; ongoing nuclear research ever since has resulted in voluminous waste, that will remain toxic longer than planning horizons. People oppose transportation of nuclear waste through their communities, so the CNSC concluded that it had to deal with waste onsite. A federal Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) was published for a nuclear waste NSDF.

Disturbingly, assessment of the natural environment is absent from the federal EIS, so the Algonquin First Nations retained experts and published Assessment of the CNSC NSDF and Legacy Contamination in June 2023.

The federal assessment found that the top risk for stability of hillside waste disposal was severe rainfall. Too much rain could sweep the nuclear waste down the hill and into Perch Lake, polluting Perch Creek and the Kitchi Sibi River a kilometre away. This could pollute the ecosystem and food sources, as well as drinking water for millions of people downstream in smaller towns, Ottawa and cities.

On Aug. 10, 2023, at the sacred site where the Rideau, Kitchi Sibi and Gatineau rivers tumble together, Chiefs of Kebaowek, Kitigan Zibi Anishinabeg and Mitchibikonik Inik First Nations, Elders and other experts, made final submissions to the CNSC. As witnesses spoke, attendees heard a roar of rain drumming on the roof.

This rain flooded Ottawa streets and basements, stopped traffic, took out power, and backed up sewers. Five centimetres of rain fell in an hour, and more than 300 million litres of untreated water flowed into the Ottawa River.

The EIS vastly under-estimates future weather severity, defining “heavy rainfall” as over only 0.7 cm per hour. The EIS also cites a 2013 estimate of low tornado risks—an insult to fresh memories of catastrophic tornadoes and derechos in Eastern Ontario.

The acceleration of climate disasters is boggling Canada’s long-term predictions of the scale of extreme weather. The nuclear waste disposal facility was designed to withstand end-of-the-century estimates of less than five cm of precipitation in a day for Deep River, and over five cm in a day—not an hour—for Ottawa.

Ottawa’s not alone in breaking rainfall records and disproving future estimates. July 2023 brought rainfall disasters to Nova Scotia, with rainfall up to 50 cm per hour measured in one location. Much of the province experienced 20 cm in a day, causing widespread damage. Canadian federal climate predictions call for much less—up to 9 cm in a day by the end of the century.

If an Environmental Impact Assessment for a bridge was discovered to be this flawed—that the bridge would not withstand a storm as severe as what just occurred—it would be a good reason to reconsider the plans. The Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission should heed the warning from Mother Nature and deny the present proposal.

2

New Brunswick Indigenous communities and Canadians need facts about Small Modular Nuclear Reactors, not sales hype.

Until the government shares facts instead of sales pitches for small modular nuclear reactors, Indigenous nations must assume that representation is not connected to people, but to industry.

BY HUGH AKAGI AND SUSAN O’DONNELL | September 28, 2023

FREDERICTON, N.B.—Governments and other nuclear proponents are failing both Indigenous and settler communities by promoting sales and publicity material about small modular nuclear reactors (SMNRs) instead of sharing facts by independent researchers not tied to the industry.

For decades, nuclear proponents, including both the federal and New Brunswick governments, have focused on the ‘dream of plentiful power’ without highlighting the risks. The nuclear fuel chain—mining uranium, chemically processing the ore, fabricating the fuel, fissioning uranium in a reactor creating toxic radioactive waste remaining hazardous for tens of thousands of years—leaves a legacy of injustices disproportionately felt by Indigenous Peoples and all our relations.

Now the same is happening with the push for SMNRs. We are promised safer reactors by nuclear startup companies in New Brunswick using modifications of reactor designs—molten salt, sodium cooled—that have never operated successfully and safely on a grid anywhere despite billions of dollars of public funds spent in other countries.

Only one example of the misguided SMNR sales pitches for Indigenous and settler communities in New Brunswick is that used CANDU reactor fuel can be “recycled” to make new fuel. The technical name for this process is “reprocessing.” Calling it “recycling” is a buzzword meant to reassure people because the truth is impossible to accept. Less than one per cent of the used fuel at Point Lepreau is plutonium and other elements that could possibly be extracted and re-used for new fuel. The more than 99 per cent left over will be a toxic mess of new kinds of nuclear waste that nobody knows how to safely contain.

The reprocessing method planned for New Brunswick is based on a technology developed by the Idaho National Laboratory, which has spent hundreds of millions of dollars so far, over two decades, attempting to reprocess a small amount of used fuel.

In different countries, commercial reprocessing has been an environmental and financial disaster. In just one example, a small commercial reprocessing plant in the United States operated for six years—heavily subsidized by the federal government and New York state—before shutting down for safety improvements. After the owner abandoned the project in the 1970s, the multi-billion-dollar cleanup continues today.

The research on reprocessing used fuel is clear: it’s an expensive nuclear experiment that could leave a multi-million-dollar mess affecting entire ecosystems and the health of people and other living beings. Why are governments sharing sales and promotional material about the project, and fantasies about ‘recycling’ instead of facts about reprocessing and the experiences in other countries? Why are New Brunswickers and First Nation leaders not demanding the evidence?

The lack of transparency by governments on the risks of SMNRs indicates that either they are not concerned with the risks, or they choose not to share them—the opposite of what is required under the United Nations Declaration of Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

Much of society’s standards for integrity have been lost. We accept circular references, we accept that no one is declaring a conflict of interest in conversations surrounding nuclear. When our integrity is lost, so is our quality of life. Words such as “protect” and “conservation” have no meaning anymore. Though we use the terms “transparency” and “accountability” more and more often, they have less and less meaning.

The Peskotomuhkati Nation in Canada and Wolastoq Grand Council cannot provide consent for any new nuclear developments in New Brunswick without considering the lessons they have learned in the past, the current relationships and communications they are experiencing, and the impacts of toxic wastes that remain dangerous forever. First Nations in New Brunswick cannot provide consent for toxic radioactive waste to be sent to Ontario, where Indigenous nations also do not want it on their territories.

The Wolastoq Grand Council, which issued a statement on nuclear energy and nuclear waste in 2021, opposes any destruction or harm to Wolastokuk which includes all “Flora and Fauna” in, on, and above their homeland. Nuclear is not a green source of energy, or solution to a healthier future for our children, grandchildren and the ones who are not born yet. Wolastoqewi-Elders define Nuclear in their language as ‘Askomiw Sanaqak,’ which translates as ‘forever dangerous.’

The Peskotomuhkatik ecosystem includes Point Lepreau. The Peskotomuhkati leadership in Canada has repeatedly tried to bring facts about both New Brunswick SMNR projects and their potential environmental implications to the attention of New Brunswickers and all Canadians, writing twice to Environment and Climate Change Minister Steven Guilbeault urging him to designate the SMNR projects in New Brunswick for a federal impact assessment, so that all the facts could be made public. Both attempts were denied, the most recent in August this year.

Peskotomuhkati leadership has participated, and continues to participate, in Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission and various provincial processes, and has firsthand experience that these past and current engagement and assessment tools do not provide a sufficient framework to address adverse effects and impacts to Indigenous rights.

The SMNR projects planned for Point Lepreau within Peskotomuhkatik homeland will have profound and lasting impacts on Indigenous rights as well as those of Indigenous communities in Ontario where the nuclear industry is proposing to build a deep geological repository for the used nuclear fuel and other sites for intermediate radioactive waste. The SMNR projects will also have profound and lasting impacts on the Bay of Fundy, the marine life the bay supports, and coastal communities.

Until the government begins to ask for and share facts about SMNRs instead of sales materials, Indigenous nations must assume that representation no longer means peoples’ representation, but rather representation of the industry.

Hugh Akagi is chief of the Peskotomuhkati Nation in Canada. Dr. Susan O’Donnell is the lead investigator of the CEDAR research project at St. Thomas University in Fredericton

Uranium Mining Protections Needed Across the West

The Biden administration needs to protect communities and water supplies across the West from the dangers of uranium mining.

Geoffrey H. Fettus Senior Attorney, Nuclear, Climate & Clean Energy Program

President Biden’s designation of the Baaj Nwaavjo I’tah Kukveni—Ancestral Footprints of the Grand Canyon National Monument will go far in protecting the rich cultural and ecological value of this majestic landscape. It will safeguard some of the most iconic public lands in the American West from the ravages of destructive mining and destructive waste. This protection has been a top priority for tribes in the area, and the designation is long overdue.

“That’s our aboriginal homelands,” Dianna Sue Uqualla, a Havasupai tribal council member, told the Bureau of Land Management at a public meeting according to Bloomberg Law. The monument will “keep at bay these mining people that are coming in,” and will protect the Grand Canyon from companies that are “desecrating, raping the Mother Earth.”

This is wonderful news, but there is much more to be done about uranium mining across the American West. And there’s also a lot of misinformation out there that muddies what should be a clear path forward to protecting all the people and watersheds of the West from unchecked uranium mining.

Uranium mining contaminated tribal lands for decades

The uranium mining industry has left a dreadful history of contamination and harm across vast swathes of the American West, but especially with respect to the Indigenous People who call this area home. It’s a complicated history that intertwines with the Manhattan Project and the Cold War, and it’s a legacy that has yet to be addressed.

On Navajo land alone, nearly four million tons of uranium ore were extracted from 1944 to 1986. The industry and the U.S. government left behind hundreds of abandoned uranium mines, four inactive uranium milling sites, a former dump site, and the widespread contamination of land and water; this includes the 1979 collapse of a tailings dam in Church Rock, New Mexico, that deposited 93 million gallons of radioactive and chemically contaminated liquid and 1,100 tons of solid radioactive tailings into the Rio Puerco, contaminating the river for more than 60 miles downstream. After decades of pressure, the government has finally started to assess and mitigate this contamination.

Much is left to be done: More than 500 abandoned uranium mines remain on Navajo land.

We need new standards

Back in 2016, the Obama administration was poised to take action on uranium mining standards, but then Donald Trump was elected president. It will come as no surprise that the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) under the Trump administration cast aside the Obama EPA’s long-overdue protective environmental standards. In an about-face, the Trump EPA and Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) moved to weaken uranium mining rules.

Once Biden took office in 2021, NRDC had hoped for a new approach. So far, however, we haven’t heard anything from either the EPA or NRC, despite repeated requests by NRDC and other major environmental groups, tribal representatives, and regional groups across the West.

It is time for the EPA to clear the obstacles and move forward on the uranium protections it drew up years ago.

The Biden administration can begin to protect the communities and water resources that have been negatively affected by uranium mining for decades by taking two steps: (1) dissolving a 2020 memorandum of understanding between the EPA and NRC that undercuts the EPA’s ability to enact standards; and (2) issuing protective uranium in situ mining standards that have been sitting on a shelf for years. ……………………………………………………………….

British activists join Nuclear Free Local Authorities in supporting Swedish Sami against uranium mining

The UK/Ireland Nuclear Free Local Authorities and Lakes against the Nuclear Dump have been joined by activists from twelve anti-nuclear campaign groups in a letter to organisations representing the Sami people of Sweden offering support in their fight against uranium mining.

A ban on uranium exploration, mining and processing in Sweden came into force on 1 August 2018 but, last month, Swedish Climate Minister Romina Pourmokhtari announced that the ban would be lifted and that ten new nuclear reactors would be built over the next twenty years. In the face of international and domestic criticism, the centre-right government has since reined in the commitment to new nuclear by talking instead of a vague commitment to developing ‘green power’, but there has been no roll-back on uranium mining.

Sweden accounts for 80% of the European Union’s uranium deposits and already extracts uranium as a waste product when mining for other metals. Foreign companies, including Aura Energy and District Metals, have already expressed an interest in exploiting reserves. Even if the new government’s nuclear hopes come to naught, there will still be a ready export market for any output. The ongoing conflict in Ukraine has made the surety of uranium supply from Russia and its allies uncertain and the recent military takeover in uranium-producing Niger has shaken the market; consequently, pro-nuclear European nations will be looking for any stable source from a neighbour.

The correspondents fear that any resumption of uranium mining will come at a heavy price to the traditional lands and lifestyles of the Indigenous Sami People, with a degradation of their natural environment and their health. The Sami (or Saami) inhabit the region of Sápmi, which embodies the most Northern parts of Norway, Sweden and Finland, and North West Russia, and are best known for their reliance upon semi-nomadic reindeer herding.

Councillor Lawrence O’Neill, Chair of the NFLA’s Steering Committee, said: “Sadly the world over, uranium mining has been, and still is, often visited upon Indigenous People in their Traditional Lands by large, profit-hungry corporations. In addition, national governments have chosen their lands to carry out nuclear weapons testing and nuclear waste dumping. The impact has been enormous – the lands of Indigenous People have been poisoned, their health destroyed and their culture and traditional way of life decimated.

“Sweden has signed the UN Declaration of the Rights of Indigenous People pledging to defend the lands and lifestyle of the Sami, but the decision to resume uranium mining could, if left unchallenged, lead to their destruction. In sending this collective letter, we, the British and Irish local authorities opposed to nuclear power, with British anti-nuclear groups and activists are pledging ourselves as allies in this fight”.

Co-sponsor, Marianne Kirkby, founder of LAND, Lakes against the Nuclear Dump, added: “Here in Cumbria, we feel so much empathy for the Sami people who have had no say whatsoever in the opening-up of Sweden’s wild areas to the devastation of uranium mining.

“In the UK, we have no uranium mining, but plenty of nuclear plants. We are constantly told that nuclear power is ‘clean’ and ‘home-grown’. This blatant lie is the means by which Sami lands are put under pressure for new uranium mining exploitation in areas where it was previously, and quite rightly, banned as being too destructive to the health of people and planet”.

“This lie of ‘clean nuclear’ is the means by which Indigenous people, whether in Cumbria or in Sweden, whether at the waste end or the fuel end of the nuclear industry, are being exploited by the most toxic industry there is without even a ‘by your leave’. We stand in solidarity with the Sami in saying NO – NO MORE!”

The deep roots of the Yucca Mountain nuclear waste fight — and why it continues to this day

Sep 05, 2023, By: Paulina Bucka, https://www.ktnv.com/news/the-deep-roots-of-the-yucca-mountain-nuclear-waste-fight-and-why-it-continues-to-this-day?mibextid=2JQ9oc&fbclid=IwAR2n8wFDd8P4EIq0HqFMPy2ASLEGa_caRDfN8zyxddED3YKpB-bNpPAV8H4

YUCCA MOUNTAIN (KTNV) — For Nevada, it’s the question that doesn’t go away.

The fight to stop Yucca Mountain from becoming a nuclear waste repository has gone on for more than three decades now. Despite an official halt to the project in 2010, that fight continues for Nevada’s Congressional delegation and the Western Shoshone people.

For the Western Shoshone, it’s a cause large than themselves — a calling to preserve their identity for generations to come.

“For the Shoshone people, our identity is the land,” said Ian Zabarte, principal man of the Shoshone Nations. “We developed our language in relation to the land — to be able to talk about it, to be able to share it.”

For decades, those ties have been threatened by the radioactive fallout of nuclear testing.

“You used to be able to drink the water from any of the springs around you,” Zabarte said. “Now, you can’t do that any more because of the pollution.”

One hundred miles northwest of the bright lights of Las Vegas, miles past Mercury, Nevada, sits Yucca Mountain — a 60-million-acre formation made up of mostly fractured volcanic tuffs.

It’s almost home to the Western Shoshone Nation people — a home Zabarte says he hopes to see restored to its most natural form within his lifetime.

Some of the big pollution is radioactive fallout from the nuclear weapons testing,” Zabarte said. “We cannot just pick up and leave in the event of the radiation, the fallout — we lose our identity.”

Zabarte has spent his life on the front lines of the fight to keep nuclear waste out of his ancestral home.

“We would walk all the way across the valley to the main gate at the Nevada Test Site doors and have our protests there,” Zabarte said. “I received a letter in 2001 that said I’m at risk of developing silicosis because of the number of hours I spent underground at Yucca Mountain.”

While the U.S. no longer performs nuclear testing, nuclear advances continue, and questions about what happens to the nation’s nuclear waste remain.

“After testing, Nevada was angry enough about what had happened because of nuclear weapons testing that it said, ‘Never again. We’re not going to be the high-level waste dump for this country,'” said Kevin Kamps, a radioactive waste specialist.

Kamps has walked alongside the Shoshone Nation people for decades in protest of nuclear testing and the proposed repository that would have sat roughly 1,000 feet under Yucca Mountain.

“What happened in our state was Nevada never had consent, and in 1982, when the bill was passed that designated Nevada as the nation’s nuclear storage waste disposal area, that didn’t come with any of our consent,” said Rep. Susie Lee, a Democrat representing Nevada’s 3rd Congressional District.

The late U.S. Senate Majority Leader Harry Reid spent his career leading the battle against the project, which began in the 1980s, during President Ronald Reagan’s administration.

President Barack Obama called the Yucca Mountain project “unworkable” in 2010 and made good on his campaign promise to Nevadans to end it and cut funding for the project.

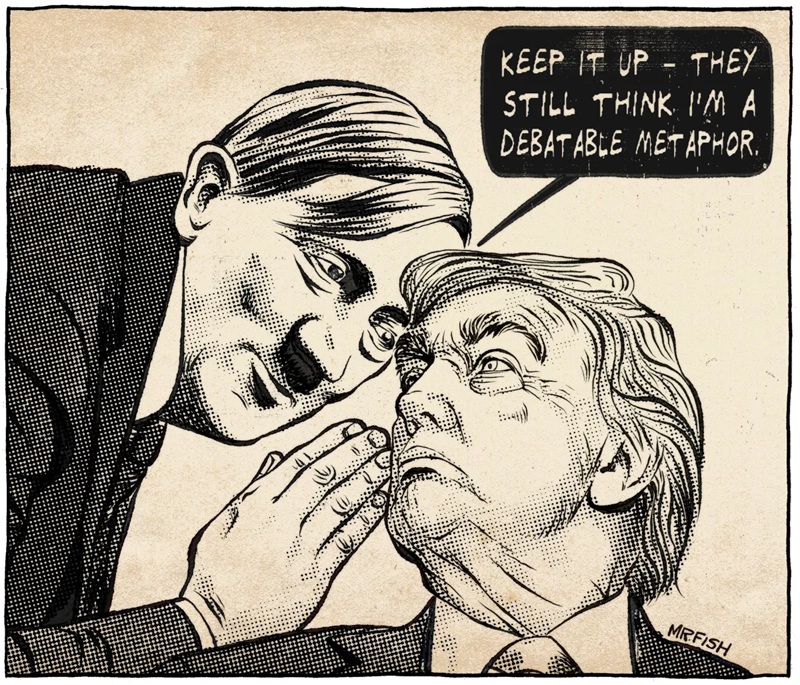

“This was a political cartoon that ran in the Las Vegas Review-Journal back in 2010, and it really celebrated the end of the Yucca Mountain Project, this attempt by the U.S. government to attempt to dump all the country’s high radioactive waste here in Nevada,” Kamps said.

Ten years later, President Donald Trump — a supporter of nuclear energy — initially called for the licensing process of Yucca Mountain to restart. But in 2020, Trump announced that he would reverse his policy and halted his support of the project.

Today, the question still remains: Where should the nation’s nuclear waste be stored? It’s a near-constant fight for members of Nevada’s congressional delegation to this day.

“The fact of the matter is, there are 27 states that have nuclear waste, spent fuel from nuclear reactors, and those states want a solution,” Lee said.

Lee says the bipartisan position from Nevada lawmakers is clear: Nevadans don’t want to see any funding go back into the Yucca Mountain project.

“There will need to be a long-term solution for this,” she said. “I’m working with my counterparts to try and come up with a solution, how we can reprocess that waste, but most importantly, how and where it can be put where there is consent.”

For the Shoshone Nation lineage, the Yucca Mountain fight goes beyond politics. Its members say it’s a race to preserve what’s left of the mountain to leave behind for future generations.

“They say that we are as naive as Native Americans because of our holistic conservation of the land for future generations,” Zabarte said. “They don’t see that as value, that the land is somehow being wasted.

“We’re trying to protect this land so our future generations can live a good quality of life,” he said.

Marshall Islands reacts to US expansion of nuclear compensation

Marianas Variety, By Giff Johnson – For Variety Aug 21, 2023

MAJURO — Within days of United States congressional leaders and executive branch officials telling Marshall Islands leaders there was no more money for nuclear test compensation, the U.S. Senate passed legislation expanding nuclear compensation to more Americans in the U.S. mainland and also living on Guam.

The Senate legislation seeks to expand the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act of 1990. This law currently provides compensation to American Downwinders who lived near the Nevada Test Site, uranium miners, and people who worked at nuclear sites.

The new legislation expands the time period of eligibility for uranium miners from the previous deadline of 1971 to 1990, which means many more workers will be eligible. It also aims to support compensation for people in Guam — who live over a thousand miles away from the Bikini and Enewetak test sites in the Marshall Islands — and other U.S. jurisdictions affected by nuclear testing.

In the Marshall Islands, however, the U.S. definition of those “exposed” is limited to four atolls despite U.S. government studies that show many more islands in the country were exposed to nuclear test fallout. Prior to it running out of compensation funds in the late 2000s, the Nuclear Claims Tribunal compared fallout exposures of American Downwinders and Marshallese. It noted that the highest exposures among American Downwinders were lower than the lowest exposures of Marshallese.

The irony of the U.S. nuclear test compensation disparity is not lost on Marshallese.

“As nuclear test victim ourselves, we support compensation for American victims of nuclear tests, whether they are Downwinders or worked at nuclear test sites or worked in uranium mines,” Marshall Islands Speaker Kenneth Kedi, who represents Rongelap, was quoted Friday in the Marshall Islands Journal. “But the fact that U.S. authorities can tell the Marshall Islands there is ‘no more money’ for nuclear test exposure for people who lived through 67 of the largest US nuclear weapons tests ever conducted while at the same time preparing to expand compensation coverage for Americans is astounding.”

The U.S. government launched its Radiation Exposure Compensation Act in 1990 with a $100 million appropriation from the Congress. Over 30 years later, the U.S. Justice Department has paid out awards amounting to over $2 billion because when additional compensation was needed, the U.S. Congress appropriated more funding.

In contrast, for the Marshall Islands, which was subjected to weapons testing over 90 times the megatonnage of the Nevada nuclear tests, the U.S. provided the Marshall Islands with a $150 million fund as the “full and final” compensation and has refused to respond to Marshall Islands government requests to provide additional compensation in the ensuing 37 years since the first Compact of Free Association went into effect. Despite the fact that the Nuclear Claims Tribunal was an entity created by the first Compact of Association to adjudicate nuclear claims, the Marshall Islands government’s entreaties to the United States for funding to pay the over $3 billion in Tribunal awards have received a cold shoulder.

“We have no issue with people of Guam qualifying for U.S. nuclear compensation,” Kedi commented. “But if the people of Guam, who are 1,400 miles away from Bikini, are eligible for compensation, what about the many Marshallese who lived much closer to the testing who according to the U.S. are not radiation affected?”

The Tribunal award for Rongelap Atoll, which was not paid for lack of funds, is the largest of the Tribunal awards for four U.S.-acknowledged nuclear affected atolls of Bikini, Enewetak, Rongelap and Utrok — in part due to the need to fund cleanup of dozens of islands that remain radioactive from a snowstorm of radioactive fallout from the 1954 Bravo hydrogen bomb explosion at Bikini…………………………………………………….more https://www.mvariety.com/news/marshall-islands-reacts-to-us-expansion-of-nuclear-compensation/article_72b6eb98-3f55-11ee-ac0f-53b4fd3eeff1.html—

Background to Proposed radioactive waste dump in Deep River -opposition from indigenous and non-indigenous groups

| Gordon Edwards 11 Aug 23 |

A consortium of multinational corporations, headed by SNC-Lavalin, was hired by the government of Canada in 2015 to “reduce the liability” associated with federally owned radioactive wastes. The dollar value of that liability has been estimated to exceed $7 billion.

For the last 5 1/2 years, the consortium has been proposing to store the most voluminous waste in a “megadump” intended to hold about one million cubic metres of radioactive and nonradioactive toxic wastes in perpetuity. The proposed dump is essentially a landfill operation one kilometre from the Ottawa River, a heritage river that courses through the nation’s capital and feeds into the St Lawrence River at Montreal.

The project is opposed by all but one of the 11 Algonquin communities on whose unsurrendered territory the megadump is to be sited. It is part of the Chalk River Nuclear Laboratories site – land that was stolen from the Algonquin Nation in 1944. The federal government expropriated the site on national security grounds, required for the World War II Atomic Bomb Project, without asking or notifying or compensating the Algonquins for whom the site had cultural and religious significance for thousands of years.

On Thursday August 10, 2023, three Algonquin communities gave their final arguments to two members of the Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission (CNSC). Both of these Commissioners had previously worked for many years for the nuclear industry. The Algonquins were not allowed to present in person before the Commissioners, so they rented a hall for $8000 and had their own live audience to witness the proceedings as they made their presentations to the Commissioners by zoom.

In addition to Chiefs, elders, councillors, researchers and lawyers from three Algonquin communities – Kebaowek First Nation, Kitigan Zibi Anishinabeg, and Barriere Lake First Nation – there were in attendance members of several Algoquin communities, as well as many non-Indigenous people. The latter included representatives from federal parliamentarians, mayors of local communities, Ottawa city councillors, and representatives of the following Non-Governmental Organizations:

Ottawa Riverkeeper, Grennspace Alliance of Canada’s Capital, Ecology Ottawa, Ottawa River Institute, Canadian Coalition for Nuclear Responsibility, Canadian Environmental Law Association, The Atomic Photographers’ Guild, First United Church Water Care Allies, Old Fort William Cottagers’ Association, Ottawa Charter of the Council of Canadians, Sierra Club Canada Foundation, Pontiac Environmental Protection, Friends of the Earth, Ottawa Raging Grannies, Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society (Ottawa Valley), Biodiversity Conservancy International, Bonnechere River Watershed Project, Council of Canadians Regional, Coalition Against Nuclear Dumps on the Ottawa River, National Capital Peace Council.

Mony of the non-Indigenous representatives who came to hear the Algonquin Nations final arguments before the Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission (CNSC) signed their names to the following statement:

“NO CONSENT, NO DUMP. August 10, 2023″Today, CNSC conducts its final hearings on the planned ‘megadump’ at Chalk River – a gigantic mound of radioactive and non-radioactive toxic wastes, seven stories high, one kilometre from the Ottawa River. Most of the radionuclides to be dumped have half-lives of more than 5000 years. 99 percent of the initial radioactivity is from profit-making companies – waste that is imported for permanent disposal at public expense.

“Chalk River is sited on the unceded traditional territory of the Algonquin Nation. The Kebaowek and Kitigan Zibi Anishinabeg Algonquin communities do not consent to this radioactive and toxic dump, which is euphemistically called a Near Surface Disposal

Facility (NSDF).“We are non-Indigenous citizens. We do not presume to speak on behalf of Indigenous peoples, but as proud Canadians we wish to state clearly that if CNSC grants permission for the NSDF despite the lack of free, prior and informed consent from the Kebaowek and Kitigan Zibi Anishinabeg, it will be an act that dishonours all Canadians.

“We – and many others across Canada – regard such a decision as a blow to the process of reconciliation. It will set a dire precedent by suggesting that Indigenous consent is not a priority. Such a development could set back the cause of reconciliation for generations.”[56 signatures by attendees]

TODAY. Nuclear trash on indigenous land ?- a court decision puts Australia in a very difficult spot

Nuclear waste on Aboriginal land ?- and the Voice to Parliament?

The Australian government is in the process of holding a referendum that would give the indigenous people a Voice to Parliament. Imposing nuclear waste on Aboriginal land is not a good look, is it?

This morning, I heard Professor Ian Lowe, talking to a English journalist, about yesterday’s court decision, which supported the Barngarla people’s opposition to nuclear waste dumping on their land.

Prof Lowe eloquently summarised the importance of this legal decision:

-the Aboriginal people were not consulted when the Morrison Liberal Coalition decided to make a nuclear waste dump on their traditional land.

– this raises problems for the Australian government in selecting any land in this country for nuclear waste dumping

-this has international implications – about any country where the rulers want to impose a nuclear waste dump on indigenous land

-this has implications for the ill-advised (corrupt firm PWC was the advisor) AUKUS decision by the Albanese government to buy U.S nuclear submarines at $369billion. That decision included Australia taking responsibility for the high level radioactive trash from the nuclear submarines. Where to dump that trash?

Of course, the Australian government does have the power to impose the nuclear waste dump anyway, against indigenous wishes, even against South Australian State government wishes,

The Australian government is in the process of holding a referendum that would give the indigenous people a Voice to Parliament. Imposing nuclear waste on Aboriginal land is not a good look, is it?

Nuclear waste issue must be resolved before new facility can be explored, says Saugeen Ojibway Nation

APTN News, By Kierstin Williams, Jul 11, 2023

The Bruce Nuclear Station was built in the 1960s without the consultation or consent of the Saugeen Ojibway Nation.

The Saugeen Ojibway Nation is not making any commitments on the proposed expansion of the Bruce Power nuclear plant until the issue of whether nuclear waste will be stored on its territory is resolved.

Last week, Todd Smith, Ontario’s minister of energy, announced preliminary studies with Bruce Power to explore the expansion of Canada’s largest nuclear plant. The expansion would see an additional 4,800 megawatts of nuclear generation at the site.

The Bruce Power Nuclear Generating Station is located on the eastern shore of Lake Huron, the traditional territory of the Saugeen Ojibway Nation (SON), which is comprised of Saugeen First Nation and the Chippewas of Nawash First Nation.

“We have stated clearly that SON will not support any future projects until the history of the nuclear industry in our Territory is resolved and there is a solution to the nuclear waste problems that is acceptable to SON and its People,” said both chiefs in a letter on behalf of Saugeen and Nawash.

SON says the Bruce Nuclear Station was built in the 1960s without its consultation or consent.

The Nuclear Waste Management Organization (NWMO), the federal agency responsible for the long-term management of Canada’s used nuclear waste, plans to select a host site for its proposed deep geological nuclear waste facility by the fall of 2024. The facility would hold used nuclear fuel in a vault approximately 500 metres underground.

The two possible sites are within Saugeen Ojibway’s traditional territory and Wabigoon Lake Ojibway Nation near Ignace, Ont.

“The long overdue resolution of the nuclear legacy issues must occur before any future project is approved,” said Chief Conrad Ritchie and Ogimaa Kwe Veronica Smith in the letter. “Similarly, we must also have a plan in place that has been agreed to by SON to deal with all current and future nuclear waste before any future projects could go ahead.

“In no way does this announcement commit the SON to new nuclear development on SON territory,” added the letter posted on the band’s Facebook page…………………………………………..

In response to SON’s letter, NWMO said the storage site plan “will only proceed in an area with informed and willing hosts, where the municipality, First Nation communities, and others in the area are working together to implement it.

“This means the proposed South Bruce site would only be selected to host a deep geological repository with Saugeen Ojibway Nation’s willingness,” said the NWMO. https://www.aptnnews.ca/featured/nuclear-waste-issue-must-be-resolved-before-new-facility-can-be-explored-says-saugeen-ojibway-nation/

First Nations won’t back nuclear plant expansion until waste questions are answered

By Matteo Cimellaro | July 7th 2023 (The National Observer) https://www.nationalobserver.com/2023/07/07/news/first-nations-wont-back-nuclear-plant-expansion-until-waste-questions-are-answered#:~:text=Two%20First%20Nations%20near%20the,obtained%20by%20Canada’s%20National%20Observer.

Two First Nations near the proposed expansion of Canada’s largest nuclear power plant will not support any new projects until there is a solution to the nuclear waste problem on their territory, the Saugeen Ojibway Nation wrote in a letter to its membership obtained by Canada’s National Observer.

Bruce Power, the operator of the Bruce Nuclear Generating Station, will have to demonstrate safe nuclear waste management, the Ontario government said in a press release announcing the province’s first large-scale nuclear development in three decades. However, the release stopped short of mentioning the development of a deep geological repository set to be the solution for long-term nuclear waste storage for the country.

The Saugeen Ojibway Nation, composed of the Saugeen First Nation and the Chippewas of Nawash Unceded First Nation, is one of two possible hosts for the Nuclear Waste Management Organization’s (NWMO) proposed nuclear waste facility, along with Ignace, Ont., located 250 kilometres northwest of Thunder Bay.

The NWMO, a Canadian non-profit tapped to address the disposal of used nuclear fuel, will select a site to store Canada’s nuclear waste roughly 500 feet underground — as deep as the CN Tower is high — in a geological repository in March 2024.

“Until the Saugeen Ojibway are comfortable on the plan on how we’re going to resolve that waste issue, it’s really hard for us to buy into 100 per cent of what the province is doing,” Veronica Smith, chief of the Chippewas of Nawash Unceded First Nation, told Canada’s National Observer.

There will be compensation for the communities chosen to host the deep geological repository, Smith added. But it’s unclear if host First Nations might benefit from a nuclear waste facility revenue-sharing model or a lump sum payment. Those conversations haven’t even started between Saugeen Ojibway Nation and the NWMO, Smith said.

It’s also unclear if community members of both First Nations will be comfortable with the NWMO’s plan for a nuclear waste facility. Smith notes community members are the ultimate decision-makers over a proposed agreement to host the waste facility, not the elected chief and council.

Nishnawbe Aski Nation, the political organization that represents 49 First Nations in northern Ontario, including all those in Treaty 3 where the Ignace site is located, has vehemently opposed building the waste facility in the North. In 2022, the organization passed a resolution stating concerns over watersheds that lead up into Hudson Bay.

Within the northern First Nations, there are also worries a nuclear spill from transport trucks carrying waste could cut off the northern communities’ winter road access, cutting a vital supply route to several communities.

“What is NWMO going to say if both communities say no?” Smith asked.

In its letter to membership, the Saugeen Ojibway Nation also wrote that it wants a resolution and reconciliation over the historical legacy issues of nuclear power on their territory.

In the 1960s, the Bruce Power Station, one of the largest nuclear power stations in the world, was constructed on Saugeen Ojibway Nation’s territory without consultation and consent.

“What is NWMO going to say if both communities say no?” Smith asked.

In its letter to membership, the Saugeen Ojibway Nation also wrote that it wants a resolution and reconciliation over the historical legacy issues of nuclear power on their territory.

In the 1960s, the Bruce Power Station, one of the largest nuclear power stations in the world, was constructed on Saugeen Ojibway Nation’s territory without consultation and consent.

Local colleges train students to work in a plutonium pit factory, but at what cost?

It carries a legacy of illness, death and environmental racism for countless others. History tells of a long practice of hiring local Hispano and Pueblo communities to staff some of the most dangerous positions.

History tells of a long practice of hiring local Hispano and Pueblo communities to staff some of the most dangerous positions, a practice that has its origins in the early years of the lab, as Myrriah Gómez describes in her 2022 book Nuclear Nuevo México.

- By Alicia Inez Guzmán Searchlight New Mexico, Jun 10, 2023 https://www.santafenewmexican.com/news/local_news/local-colleges-train-students-to-work-in-a-plutonium-pit-factory-but-at-what-cost/article_068bd3b2-0589-11ee-b8ba-93e1230989e7.html

Every day, thousands of people from all parts of El Norte make the vertiginous drive up to Los Alamos National Laboratory. It’s a trek that generations of New Mexicans have been making, like worker ants to the queen, from the eastern edge of the great Tewa Basin to the craggy Pajarito Plateau. All in the pursuit of “good jobs.”

Some, inevitably, are bound for that most secretive and fortified place, Technical Area 55, the very heart of the weapons complex — home to PF-4, the lab’s plutonium handling facility, with its armed guards, concrete walls, steel doors and sporadic sirens. To enter “the plant,” as it’s known, is to get as close as possible to the existential nature of the nuclear age.

For 40 years, some 250 workers were tasked, mostly, with research and design. But a multibillion-dollar mission to modernize the nation’s nuclear arsenal has brought about “a paradigm shift,” in the words of the Defense Nuclear Facilities Safety Board, a federal watchdog. Today, the plant is in the middle of a colossal expansion — growing from an aged building to what the safety board calls “a large-scale production facility for weapon components with the largest number of workers in its history.”

In short, the plant is slated to become a factory for making plutonium pits, the essential core of every nuclear warhead.

Four years ago, LANL began laying the groundwork for this expansion by searching out and shaping a highly trained labor pool of technicians to handle fissile materials, machine the parts for weapons, monitor radiation and remediate nuclear waste. The lab turned to the surrounding community tapping New Mexico’s small regional institutions — colleges that mostly serve minority and low-income students. The plan, as laid out in a senate subcommittee meeting, set forth a college-to-lab pipeline — a “workforce of the future.”

Taken altogether, Santa Fe Community College, Northern New Mexico College and the University of New Mexico’s Los Alamos campus have accepted millions of federal dollars for their role in preparing that workforce. They’ve graduated 74 people to date, many of whom will end up at TA-55.

As Kelly Trujillo, associate dean of SFCC’s School of Sciences, Health, Engineering and Math, put it, “A lot of these jobs are high-paying jobs and they allow [workers] to stay in their home, in the area that they love.”

The trade-offs, like so much involving LANL’s history in Northern New Mexico, are not without controversy. For many local families, the lab has been a gateway to the American dream. Its high wages have afforded generations of Norteños a chance at the good life — new houses, new cars, land ownership, higher education for their kids. To work there is to become part of the region’s upper crust.

It carries a legacy of illness, death and environmental racism for countless others. History tells of a long practice of hiring local Hispano and Pueblo communities to staff some of the most dangerous positions, a practice that has its origins in the early years of the lab, as Myrriah Gómez describes in her 2022 book Nuclear Nuevo México.

New Mexico’s academic institutions have for decades served as LANL’s willing partner, feeding students into the weapons complex with high school internships; undergraduate student programs; graduate and postdoc programs; and apprenticeships for craft trades and technicians. The lab heavily recruits at most local colleges, too.

Talavai Denipah-Cook can still remember LANL representatives plying her with promises of a high-paying job and good benefits at an American Indian Sciences and Engineering Society conference years ago. At the time, she was a student at a private high school in Española, and the future that they painted looked bright.

“I was like, ‘Wow, that sounds really intriguing.’ We don’t get that around here, especially as people of color,” said Denipah-Cook, now a program manager in the Environmental Health and Justice Program at Tewa Women United, an Indigenous nonprofit based in Española.

Then she remembered the words of her grandmother, a field nurse from Ohkay Owingeh, who once tended to Navajo Nation tribal members affected by uranium mining and saw the health impacts of radiation exposure firsthand.

“She used to tell me, ‘Don’t ever, ever work at Los Alamos National Labs.’”

‘The snake road’

For nearly eight decades, LANL’s repeated attempts to expand have run up against the plateau’s geography. During the Manhattan Project, the site proved problematic in terms of housing, transportation and access along the road that old-timers called el camino de la culebra — the snake road. In more recent years, the lab’s footprint has stretched to encompass a nearly 40-square-mile campus that abuts Bandelier National Monument, U.S. Forest Service lands, the cities of Los Alamos and White Rock, and San Ildefonso Pueblo.

One of its smallest areas, TA-55, sits at the north-central edge of campus. Within is “the plant” — a 233,000-square-foot building that ranks, according to the U.S. Department of Energy, as the only “fully operational, full capability plutonium facility in the nation.”

This is where plutonium and other irradiated materials are conveyed by a trolley system from a vault to rooms lined with gloveboxes, sealed and oxygen-free. Workers, their hands protected by bulky gloves, weigh and handle plutonium in all its forms — molten, metal and powder. They disassemble and inspect existing weapons from the stockpile; forge parts for nuclear batteries that help power spacecrafts; and perfect the dimensions of plutonium “hemishells” on hand-built machines. According to a retired machinist, each pit has to be so precisely crafted that the difference between it and others can vary no more than the width of a strand of hair.

A mass of certifications and protocols are required for every task; there is little margin for error. Should radiation escape its enclosure, a radiation control technician stands by with a Geiger counter to detect it and stop work immediately.

Plant employees earn an extra $20,000 of environmental pay — in order “to attract people, quite frankly, to work in our more challenging facilities,” said Stephen Schreiber, who works in weapons production as the technical director of the lab’s office of Science, Technology and Engineering.

When Joaquin Gallegos, the former chair of NNMC’s Biology, Chemistry and Environmental Sciences Department, recruited high school students to join the college pipeline, he cited the competitive salaries and drew upon his own family history: the aunts and uncles who worked at LANL while continuing to tend multigenerational land.

The lab “subsidized” their lifestyle and made it possible not to “sell out,” Gallegos said. “People who have 10 or 15 acres of agricultural land, that’s not enough to support a family. But if you work at the labs, you could still maintain that culture. You could still raise animals and maintain that as part of your family.”

Pendulum swings for pits

It’s been almost 75 years since LANL last produced plutonium pits at an industrial scale. In 1996, the lab was sanctioned to produce up to 20 plutonium war reserve pits a year for the W88 warhead. It produced 30 pits in a five-year period, until 2012 when all major plutonium operations were suspended, after four pieces of weapons-grade plutonium were placed side by side for a photo op — a positioning that could have caused a runaway neutron chain reaction and a flash of potentially fatal radiation.

“The lab has never had to be accountable for their promises,” said Greg Mello, of the Los Alamos Study Group, an influential anti-nuclear nonprofit based in Albuquerque. “Could they be a factory? Could they produce pits reliably? No. Not at all.”

LANL, regardless, was tapped as one of two sites — the other being South Carolina’s Savannah River plutonium processing facility — to produce no fewer than 80 pits annually by 2030, according to the Fiscal 2020 National Defense Authorization Act. The law authorized LANL to produce 30 pits per year by 2026.

What’s being proposed is so huge it has no precedent, said Jay Coghlan, executive director of Nuclear Watch New Mexico, an anti-nuclear advocacy organization in Santa Fe.

“Here we have this arrogant agency that thinks it can just impose expanded bomb production on New Mexico,” said Coghlan, referring to the National Nuclear Security Administration, the lead agency for pit production. “They do not have credible cost estimates and they do not have a credible plan for production. But yet they expect New Mexicans to bear the consequences.”

The costs, according to the Los Alamos Study Group, will come to some $46 billion by 2036 — the earliest the NNSA says it can hit 80 pits per year at the two sites. It’s roughly the same amount of money it would take to rebuild every single failing bridge in America.

The NNSA estimates the lab will need 4,100 full-time employees, including scientists and engineers, security guards, maintenance, craft workers, and “hard-to-fill positions,” as LANL has dubbed the pipeline jobs.

It is the most costly program in the agency’s history. It is also destined, Coghlan and others say, to collapse under its own weight. Both Los Alamos and Savannah River are, according to federal documents, billions of dollars over budget and years behind schedule.

Money, waste and risk

More than $20 billion is slated for paying personnel and underwriting the construction in and around TA-55, including parking structures, office buildings, facilities to process transuranic liquid waste, and demolishing and decontaminating hundreds of old gloveboxes and installing hundreds of new ones. Construction is taking place at night, while staff work toward meeting LANL’s new quota by day.

Safety and controlling risk are paramount, said Schreiber, the LANL technical director. “We really do instill that in our workers.” But observers at the Union of Concerned Scientists say the pace doesn’t bode well.

“When you have new employees who are not very experienced in a new facility running new procedures in a high-risk environment — trying to do it fast, trying to meet a quota — that’s a recipe for something bad to happen,” said Dylan Spaulding, a senior scientist in the nonprofit’s global security program.

New Mexico’s all-Democratic congressional delegation, whatever the controversies, supports the project wholeheartedly. It was Heinrich and South Carolina’s Republican Sen. Lindsey Graham who rallied behind pit production in their states — ushering it into law in the 2020 National Defense Authorization Act. Then-Congressman Ben Ray Luján helped shepherd money to the pipeline programs.

Radiation 101

Last spring, assistant professor Scott Braley taught two back-to-back introductory courses to 13 future radiation control technicians at NNMC. His lectures covered a host of topics: the history of “industrial-scale” radiation accidents worldwide, algebraic formulas to determine the correlation between individual cancer and workplace exposure, and maximum permissible doses for future workers like themselves. The rates are higher than for the general public, Braley explained, because, for one, radiation workers “have accepted a higher risk.”

Once they get their associate degree, NNMC graduates proceed to the second part of their training, in a Los Alamos classroom. There, they learn how to don and doff personal protective gear — a suit not unlike the one that recent NNMC graduate Karen Padilla said she once used to keep bees. Padilla, 42, participated in simulations of scenarios that she and others might one day face, learning the proper ways to detect radiation around trash and 55-gallon barrels of waste, for instance.

“Long-term, I don’t have really any fears about this because I feel like my instructors are doing a good job of helping me understand how to protect myself” and others, said Padilla. “I think ultimately that’s my job as a [radiation control technician], to protect people who are working, to make sure they’re not getting into something that could be harmful.”

Much of the college programs center around minimizing risk. And yet they present an ethical dilemma, said Eileen O’Shaughnessy, co-founder of Demand Nuclear Abolition.

“What does it mean to assume that exposure is acceptable at all? Because the thing about radiation is it’s cumulative and any amount is unsafe.”

Generations of Northern New Mexicans have faced the same time-worn question: Are the good jobs worth the trade-offs?

“You realize, yes, they are paying you well, but you’re being put in situations that you have no idea about,” said the retired machinist, with over two decades of experience working at the lab, much of it at the plant. He asked to remain anonymous for fear of retaliation. “It’s the mentality at the lab,” he said. “They don’t really think that people that are techs are even really worth much.”

A powerful neighbor

Dueling perspectives reveal the chasms around the lab and, in particular, what some consider the Manhattan Project’s original sin: Its use of eminent domain to force Indigenous and Hispano people off their farms and sacred lands on the Pajarito Plateau. Its arrival, oral histories hold, spelled the end of land-based living.

“When did we stop farming to sustain ourselves?” Kayleigh Warren recalled asking a relative from Santa Clara Pueblo. The answer: “When the labs came in.”

Now an environmental health and justice program coordinator at Tewa Women United, Warren has borne witness to the region’s change in values. The lab has so deeply carved itself into Northern New Mexico’s psyche that imagining another future and means of survival has come to seem impossible.

As the single largest employer in northern New Mexico, LANL’s horizon of influence is vast. And with billions more dollars flooding in, its sway in almost every sphere seems only to grow.

Despite the lab’s omnipresence, economic gains have been relatively limited. While Los Alamos County has one of the highest median household incomes in the nation, the surrounding communities — including Española — are among the poorest in the state.

“LANL has been a bad neighbor,” Warren said. “If the economic benefits are so good for them to continue their work and expand, you would think the communities around here would be doing better. But we’re not.”

A nuclear site is on tribes’ ancestral lands. Their voices are being left out on key cleanup talks

KNKX Public Radio | By The Associated Press, June 23, 2023

Three federally recognized tribes have devoted decades to restoring the condition of their ancestral lands in southeastern Washington state to what they were before those lands became the most radioactively contaminated site in the nation’s nuclear weapons complex, the Hanford Nuclear Reservation.

But the Yakama Nation, Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation and Nez Perce Tribe have been left out of negotiations on a major decision affecting the future cleanup of millions of gallons of radioactive waste stored in underground tanks on the Hanford site near Richland.

In May, federal and state agencies reached an agreement that hasn’t been released publicly but will likely involve milestone and deadline changes in the cleanup, according to a spokesperson for the Washington State Department of Ecology, a regulator for the site. As they privately draft their proposed changes, the tribes are bracing for a decision that could threaten their fundamental vision for the site.

“As original stewards of that area, we’ve always been taught to leave it better than you found it,” said Laurene Contreras, program administrator for the Yakama Nation’s Environmental Restoration/Waste Management program, which is responsible for the tribe’s Hanford work. “And so that’s what we’re asking for.”

From World War II through the Cold War, Hanford produced more than two-thirds of the United States’ plutonium for nuclear weapons, including the atomic bomb dropped on Nagasaki, Japan, in 1945. Production ceased in 1989, and the site’s mission shifted to cleaning up the chemical and radioactive waste left behind.

For these tribes, which have served as vital watchdogs in the cleanup process, the area’s history dates back long before Hanford, to pre-colonization. It was a place where some fished, hunted, gathered and lived. It’s home to culturally significant sites. And in 1855 treaties with the U.S. government in which the tribes ceded millions of acres of land, they were assured continued access.

The U.S. Department of Energy, the Environmental Protection Agency and the Washington State Department of Ecology have held confidential negotiations since 2020 on revising plans for the approximately 56 million gallons of radioactive waste stored in 177 underground tanks at Hanford. The discerning eyes of the tribal experts have been kept out, though EPA and Ecology have said there will eventually be opportunities for the tribes to meet with them about this.

The revisions are expected to affect an agreement among the three agencies that outlines the Hanford cleanup. Mason Murphy, program manager for the Confederated Tribes’ Energy and Environmental Sciences program, points out that the tribes also weren’t consulted in that original 1989 agreement.

“It’s an old scabbed-over wound,” Murphy said…………………………………………………….. https://www.knkx.org/government/2023-06-23/a-nuclear-site-is-on-tribes-ancestral-lands-their-voices-are-being-left-out-on-key-cleanup-talks

—

‘We need to wake up’: Algonquin leaders sound alarm over planned nuclear waste facility near Ottawa River

By Matteo Cimellaro | News, Urban Indigenous Communities in Ottawa | June 20th 2023

Four Algonquin chiefs spoke out on Tuesday, calling out the government and its private-sector contractor over what they say are inadequate consultations over a planned nuclear waste storage facility.

Last year, the Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission (CNSC) paused its decision to move ahead with the planned waste facility, located at the Canadian Nuclear Laboratories in Chalk River, Ont. The site is 180 kilometres north of Ottawa and sits within a kilometre of the Ottawa River, otherwise known as the Kichi Sibi in Algonquin.

The pause was intended to give more time for consultations with Kebaowek First Nation and Kitigan Zibi Anishinabeg, whose traditional territories circle the Ottawa River on both sides of Quebec and Ontario.

“It’s a huge victory for us,” Coun. Justin Roy of Kebaowek First Nation told Canada’s National Observer at the time.

But now, Algonquin leaders are slamming the CNSC for failing to give adequate time for meaningful consultation. The process only lasted six months, which the leaders argued is a short time frame given the challenges of negotiating funding agreements for Indigenous-led environmental assessments.

Still, the Algonquin-led assessment found the proximity to the Ottawa River, which supplies water to millions, including Algonquins, a major red flag. The river was given status of a Canadian Heritage River by Ontario and Quebec and it holds the utmost spiritual and historical importance for the Algonquin nation.

The assessment also pointed to potential risks to Indigenous harvesting rights and the environment, including contamination concerns to local moose, migratory birds and fish.

There are also concerns about tritium, a radioactive form of hydrogen, leaching from the nuclear waste into the Ottawa River, Chief Lance Haymond of Kebaowek First Nation said.

“We need to wake up and recognize what a danger Chalk River poses not only to the Algonquin people but to all Canadians, especially those living in the Ottawa-Gatineau area,” he added.

At the press conference, Haymond was flanked by Dylan Whiteduck, chief of Kitigan Zibi, and grand chiefs Savanna McGregor and Lisa Robinson, who are leaders of the Algonquin Anishinabeg Nation Tribal Council and Algonquin Nation Secretariat, respectively.

Elizabeth May, co-leader of the federal Green Party, sponsored the press conference. In brief comments, she pointed to the primary shareholder of the company that manages Canadian Nuclear Laboratories, criticizing the decision to build the facility so close to the Ottawa River.

Canadian Nuclear Laboratories is a subsidiary of the Crown corporation Atomic Energy Limited Corporation, but it is operated under contract by the Canadian National Energy Alliance, a private-sector consortium led primarily by SNC-Lavalin. The Canadian National Energy Alliance is responsible for the daily operations of the nuclear laboratories, as well as the decommissioning and management of nuclear waste from the facilities, according to the SNC-Lavalin website.

“I don’t think we had in mind that SNC-Lavalin would once again get its way,” she said, alluding to the company’s role in a scandal that rocked the federal government four years ago.

The Algonquin leaders are also calling foul on the consultation process for a divide-and-conquer strategy of picking which Algonquin nations to consult with, which Haymond calls a “continuation of colonialism.” Pikwakanagan First Nation signed a long-term relationship agreement with Canadian Nuclear Laboratories on June 9.

“It’s a First Nation who seemed to have forgotten their responsibilities and priorities as protectors of the land, protectors of the water,” he said.

Haymond notes Pikwakanagan was given years of consultation through the controversial organization Algonquins of Ontario, which local Algonquins have accused of dividing the nation and giving free passes to false Indigenous identity claims. The organization even named a building in Algonquin at the Canadian Nuclear Laboratories site.

An official hearing for the near-surface nuclear waste facility is scheduled for Aug. 10.

“We’ve been here for millennia, the Algonquin nation and our people,” Chief Whiteduck said.

“We’re still here, and we’re gonna be here for another 1,000 years. We’re hoping to deal with these contaminants that will be poured into our river.”

— With files from Natasha Bulowski

Pacific leaders remain steadfast against nuclear waste disposal

National Indigenous Times, Gorethy Kenneth (PNG Post Courier) – May 11, 2023

Pacific has a combined voice on “no nuclear waste” in the Pacific, Prime Minister James Marape told reporters in Port Moresby on Tuesday.

He was asked by reporters if the country would support Japan on its nuclear waste issue.

Mr Marape said that he would release a statement at a later date on the latter.

Japan allegedly reported that it was due to start dumping one million tonnes of nuclear waste from the damaged Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant into the Pacific ocean in only a few months.

And according to Japan’s government, the waste water was to be treated by an Advanced Liquid Processing System, which would remove nuclides from the water.

However, the Pacific island leaders united and demanded that Japan share pivotal information about the plan.

Japan, however, assured the Pacific leaders that there was no such threat, and instead defended that the country and their government had no plans to dump more than one million tonnes of radioactive waste water into the Pacific ocean……….. https://nit.com.au/11-05-2023/5922/pacific-leaders-remain-steadfast-against-nuclear-waste-disposal-png23

-

Archives

- January 2026 (227)

- December 2025 (358)

- November 2025 (359)

- October 2025 (377)

- September 2025 (258)

- August 2025 (319)

- July 2025 (230)

- June 2025 (348)

- May 2025 (261)

- April 2025 (305)

- March 2025 (319)

- February 2025 (234)

-

Categories

- 1

- 1 NUCLEAR ISSUES

- business and costs

- climate change

- culture and arts

- ENERGY

- environment

- health

- history

- indigenous issues

- Legal

- marketing of nuclear

- media

- opposition to nuclear

- PERSONAL STORIES

- politics

- politics international

- Religion and ethics

- safety

- secrets,lies and civil liberties

- spinbuster

- technology

- Uranium

- wastes

- weapons and war

- Women

- 2 WORLD

- ACTION

- AFRICA

- Atrocities

- AUSTRALIA

- Christina's notes

- Christina's themes

- culture and arts

- Events

- Fuk 2022

- Fuk 2023

- Fukushima 2017

- Fukushima 2018

- fukushima 2019

- Fukushima 2020

- Fukushima 2021

- general

- global warming

- Humour (God we need it)

- Nuclear

- RARE EARTHS

- Reference

- resources – print

- Resources -audiovicual

- Weekly Newsletter

- World

- World Nuclear

- YouTube

-

RSS

Entries RSS

Comments RSS