Fukushima radioactive contamination: Children nosebleed while asleep and also in daytime, especially after playing in the sand!

Soil contamination survey: 80% of schools have amazing figures!!

The government and Fukushima prefecture do not measure the soil contamination, and lifted the evacuation order one after another, as “external radiation dose has come down to less than 20 mSv/year.” Besides that, Fukushima prefecture closed off in March 2017 the free housing support for voluntary evacuees. “Voluntary evacuees” are evacuees who are evacuating from areas outside the evacuation order zone. The exact number is not grasped and it is estimated to be about 17 thousand people.

For voluntary evacuees, there is no mental reparation from TEPCO, which is paid to forced refugees, 100,000 yen (~1000 $) per month, so only the free provision of housing is a lifeline. Many people will not be able to continue the evacuation life if this is cut off.

Sakamoto says, “The prefecture officials repeatedly said at the briefing session for borrowed housing termination,” We do not know about contamination of the soil, because there are people living in Fukushima. ” But this contamination situation of soil extraordinary. We, the residents in Fukushima, cannot protect ourselves if our prefecture does not clarify the details of soil contamination.”

In Fukushima prefecture, accurate information was not given to residents after the accident. Some people evacuated in the direction of radioactive plum, and many stayed outdoors for a long time in order to get water and food.

Sakamoto’s second daughter was healthy until the nuclear accident, but for some time after the accident, she suffered from symptoms such as nosebleeds, diarrhea and anemia.

“There are so many people who regret that they allowed their children exposed at that time. We hear that the staff of Fukushima Medical University took iodine, which was not given to residents. We never want children to be exposed. “(Sakamoto)

The government and the Fukushima prefecture evaluate the safety only by external radiation dose. Mr. Kono of the citizen environment research institute also alarms the danger of the evaluation.

“Since radioactive material that fell on the ground enters the soil with the passage of time, the radiation dose of the space is shielded by the soil. But it will not be eliminated from the ground and radioactive substances attached to the fine particles soar up and move. Decontaminated ground will be contaminated again and you may suck in and have internal exposure. In fact you do an exact soil survey and decontaminate the place where people live as many times as you can. If the prefecture can not decontaminate, it should give the right to emigrate to people who want to move. It is presumed to be because they do not want to reveal the seriousness of pollution that the government and prefecture do not investigate soil contamination in detail. “

Medical Doctor Ushiyama, clinical professor of Shimane University, and in charge of medical departments at Sagami Hospital, who visits medical sites in Chernobyl often, also said, “To judge safety only by radiation dose in space ignores the risk of internal radiation exposure when radioactive substances are taken into the body. “

In fact, Mr. Sawada (Fukushima-city) who found that cesium was detected from the urine of her child and she is exposed to internal radiation said:

“I was pregnant when a nuclear accident took place 5 years ago. and I evacuated to Yamagata with my 2-year-old daughter. I gave birth at Yamagata and was struggling to raise children by myself. However, since her eldest daughter became emotionally unstable and wanted to return home, I returned home in January 2014. In Fukushima city, the eldest daughter came to take a nosebleed after playing sand. Nosebleed in asleep and in daytime, and my second daughter also took nosebleed after playing outside.

Now that her eldest daughter became first grade in primary school and she does not play sand, it’s gone … …. “

Mr. Sawada says that if children have nosebleed from now on, they will think about evacuation again.

Mr. Endo (Minamisoma city) also talks like this.

“Radioactive dust is terrible because heavy duty trucks carrying decontamination soil and gravel frequently comes and goes back and forth around the school. Her son who goes to the nursery school is picked up by car, but her elder brother goes to

school by bicycle. I worry that my son will inhale the radioactive dust … ”

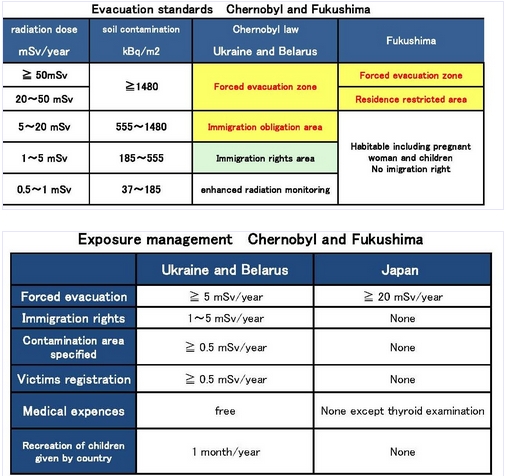

According to a survey group, soil contamination was 449,000 Bq / square meteron the school road in Minamisoma where Mr. Endo lives (around Ishigami 2nd elementary school) . In Fukushima city where Sawada lives, 480,000 Bq / square meter (around Fukushima Daiichi Junior High School) was detected. Ushiyama mentioned that Both the contamination is the value corresponding to the “move rights area” in Belarus ‘(Chernobyl).

“Even a trace amount of radioactive substances taken into the body continue to emit radiation irradiate the organs within the body until it is discharged. It いsl be difficult to get out when the radioactive substance enters the lungs. I heard from a Belarusian doctor that there is a possibility that bladder cancer increased by excretion of radioactive substance in the urine. The accumulation in genital organs is also concerned about the influence on the next generation. , It has also been reported that the abnormality worsened if insects are grown with bait contaminated with radioactive materials. “

Mothers are exhausted by the irresponsible constitution of the government and the prefecture and the social pressures that force to consider “Don’t worry, Fukushima accident never happened, everything is all right.”

Terumi Kataoka who told me the story that removed the slide says.

“Aizu is believed to have little pollution, but it depends on the location.In Aizu Wakamatsu City, the mayor has declared the safety declaration earlier so it is not even decontaminated.If you want the mayor to decontaminate previously If we asked, “Although tourists are returning, if we decontaminate now, both original and child will be lost” was rejected ”

Dynamics of Nuclear Power Policy in the Post-Fukushima Era: Interest Structure and Politicisation in Japan, Taiwan and Korea

Abstract

This article compares the different trajectories of nuclear power policy in Japan, Taiwan and Korea in the post-Fukushima era. The Fukushima nuclear accident ratcheted up the level of contention between civil activism and supporters of nuclear power in all three states. The result of this contention has been decided by the combined effects of two factors – interest structure (complexity vs simplicity) and politicisation (national level vs local level). In terms of scope, policy change has taken place in Taiwan, Japan and Korea in that order. This analysis contributes to a balanced understanding of both structural constraints and the political process in which each actor, and in particular civil activism, is able to manoeuvre.

Introduction

In the wake of President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s “atoms for peace” speech at the United Nations General Assembly in December 1953, the United States signed bilateral atomic energy cooperation agreements with its allies, including Japan, Korea and Taiwan. By providing those allies with nuclear technology, Washington intended to strengthen its defence and foreign policy, the centrepiece of which was the maintenance of nuclear hegemony and containment of the Soviet Union (Medhurst, 1997 Medhurst, M. J. (1997).

Atoms for peace and nuclear hegemony: The rhetorical structure of a Cold War campaign. Armed Forces and Society, 23(1), 571–593.[Crossref], [Google Scholar]).

Washington’s three East Asian allies, all of which suffered from a lack of energy resources, made nuclear power a major state-sponsored industry and relied on it for their industrialisation and economic development. The emergence of strong coalitions in each of these countries – consisting of conservative or authoritarian politicians, state-controlled or private electricity companies, and government bureaucrats – provided sustained support for the growth of nuclear power during the Cold War. When energy security was seriously challenged by the oil shock of the 1970s, nuclear power became the most viable source of electricity. Whereas fears of nuclear proliferation and safety concerns encouraged Western countries to retreat from nuclear power in the 1980s, reliance on nuclear power in these East Asian countries continued to grow. Not only did they become an attractive market for US vendors, but they also succeeded in developing independent nuclear power technology. In particular, Japan successfully developed its own nuclear fuel cycle technology, including enrichment and reprocessing (Kido, 1998 Kido, A. (1998). Trends of nuclear power development in Asia. Energy Policy, 26(7), 577–582.[Crossref], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar]).

Prior to the Fukushima nuclear incident, one-third of all electricity in Japan, Korea and Taiwan came from nuclear power. As of August 2016, there were 43 reactors capable of operation in Japan, six in Taiwan, and 25 in Korea. Japan has only two reactors currently in operation, but Tokyo is trying to increase that number. Nuclear power still accounts for 18.9 per cent of electricity generation in Taiwan and 31.7 per cent in Korea (World Nuclear Association, 2015 World Nuclear Association. (2015). Nuclear share figures. Retrieved from http://www.world-nuclear.org/information-library/facts-and-figures/nuclear-generation-by-country.aspx %5BGoogle Scholar]; World Nuclear Association, 2016 World Nuclear Association. (2016). World nuclear power reactors and uranium requirements. Retrieved from http://www.world-nuclear.org/info/Facts-and-Figures/World-Nuclear-Power-Reactors-and-Uranium-Requirements/ %5BGoogle Scholar]). Japan and Korea are also competitive exporters of nuclear reactors to countries that aspire to have access to nuclear energy.

The Fukushima nuclear incident of 2011 came as a shock to the nuclear power industry. Fukushima has not only escalated calls to “exit-from-nuclear” from civil activists in Japan but has also had repercussions around the world, particularly in Japan’s neighbours Taiwan and Korea. In the wake of the huge public backlash provoked by the incident, the three countries face the conundrum of how to enhance the sustainability of their economies while reducing their reliance on nuclear power. This situation prompts a number of questions. To what extent has the Fukushima incident brought about changes to existing nuclear policies in Japan, Taiwan and Korea? How has rising civil activism been translated into policy change in each of these countries, and what factors have been at work to convert the shock of Fukushima into a shift in energy policy? In addressing these questions, this article closely compares contentions involving different interest structures and levels of politicisation in the three cases. The interest structure under examination is the way in which the conflicting interests of supporters of nuclear energy and those opposing it are configured (complex or simple). The “level” of politicisation refers to the level at which the campaigns are fought (national or local).

This article is an exercise in inductive analysis, which seeks to use these cases to identify two factors that result in changes in nuclear power policy. The findings we obtain from an examination of the three cases are that the external shock (i.e. the Fukushima incident) has intensified contention; and that for a significant policy change to occur, the interest structure has to be simple (i.e. state-controlled nuclear power and the absence of new interests such as nuclear exports), and civil activism has to be able to cross partisan lines and raise contention to a nationally prioritised level.

This article consists of three parts. In the first part, we conceptualise the two factors that decided the policy direction in the three cases: interest structure and level of politicisation. In the second part, we outline the development of nuclear power and examine the development of contention between civil activists and nuclear power supporters in the three cases. In the third part, we identify some generalisations concerning changes in nuclear power policy.

Two Factors: Interest Structure and Politicisation

Despite common energy security needs and US support for the peaceful use of nuclear energy, nuclear power policies and the nuclear industries in the three countries under consideration have followed somewhat different paths of development. As a result, each case has displayed a different type of contention, but in all three cases government decisions and social consent have been equally important for changes in the nuclear power policy (Golay, 2001 Golay, M. W. (2001). On social acceptance of nuclear power. The Center for International Political Economy & the James A. Baker III Institute for Public Policy, Rice University. [Google Scholar]; Parkins & Haluza-DeLay, 2011 Parkins, J. R., & Haluza-DeLay, R. (2011). Social and ethical considerations of nuclear power development. Staff Paper #11-01, Department of Rural Economy, University of Alberta. [Google Scholar]). Changes in outcomes ranged from a minor adjustment of existing policy, through a significant change, to abandoning the use of nuclear power entirely. With this diversity of outcomes in mind, it is useful to investigate how the relevant actors – the government, pro-nuclear politicians (or political parties), electricity companies, and civil activists – have contended and/or coalesced with one another.

It is noted in the literature that the Fukushima incident brought about a big change in the public perception of nuclear power all around the world (Kim, Kim, & Kim, 2013 Kim, Y., Kim, M., & Kim, W. (2013). Effect of the Fukushima nuclear disaster on global public acceptance. Energy Policy, 61, 822–828.[Crossref], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar]). This change in public perception has led to construction delays and cost overruns that have interrupted the principal nuclear states’ attempts to lead a nuclear revival (Szarka, 2013 Szarka, J. (2013). From exception to norm – and back again? France, the nuclear revival, and the post-Fukushima landscape. Environmental Politics, 22(4), 646–663.[Taylor & Francis Online], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar]). Nevertheless, as it has become clear that the perceptual change by itself is not bringing about an immediate change in policy, analysts have also delved into the sources of policy continuity or partial change, including the impact of short-term interests (Nohrstedt, 2005 Nohrstedt, D. (2005). External shocks and policy change: Three Mile Island and Swedish nuclear energy policy. Journal of European Public Policy, 12(6), 1041–1059.[Taylor & Francis Online], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar]), the strength of links between governments and the nuclear industry (Fam et al., 2014 Fam, S. D., Xiong, J., Xiong, G., Yong, D. L., & Ng, D. (2014). Post-Fukushima Japan: The continuing nuclear controversy. Energy Policy, 68, 199–205.[Crossref], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar]), the way perceived benefits and risks affect public opinion (Park & Ohm, 2014 Park, E., & Ohm, J. Y. (2014). Factors influencing the public intention to use renewable energy technologies in South Korea: Effects of the Fukushima nuclear accident. Energy Policy, 65, 198–211.[Crossref], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar]), and the links between the social movements and party politics (Ho, 2014 Ho, M.-S. (2014). The Fukushima effect: Explaining the resurgence of the anti-nuclear movement in Taiwan. Environmental Politics, 23(6), 965–983.[Taylor & Francis Online], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar]). These individual analyses have their merits, but they have not systematically addressed the question of what mediates the conversion of an external shock into a policy change (or what impedes such a conversion). The issues we should examine are (1) the structure that determines the relationship between those who are deeply involved in the contention at a critical moment, particularly the relationship between supporters and challengers of nuclear power, and (2) the process by which the issue of nuclear power is politicised and those in power are forced to adopt (or resist) a new policy. In this article, we focus on these two factors: the interest structure (as structure) and politicisation (as process).

The first of the two factors, interest structure, may be defined as the way in which the competing interests of supporters and challengers are configured. The actors who support nuclear power and related industries differ from case to case, and the interest structure differs accordingly; depending on how the relationship between actors is formed, the interest structure takes on its own unique form, either complex or simple. This definition helps to identify the mode of contention between supporters and challengers. If the interest structure is complex, it is difficult for civil activists to fight against the supporters of nuclear power because a complex interest structure diversifies the battlefield and thus diffuses the activists’ ability to fight the supporters.

The degree of complexity of the interest structure is determined by two elements: type of ownership and whether new interests have been created. Specifically, ownership – whether nuclear power is state-owned or privatised – determines the degree of complexity. The form of ownership arises at an early stage in the introduction or development of the industry. Nuclear power that is owned by the state is mostly controlled by the state and thus has a less complex interest structure than privatised nuclear power. If nuclear power is state-owned and controlled, when there is serious contention over the issue, the fate of nuclear power will depend on government decisions. In contrast, if the industry is privatised and thus managed by electricity companies, the interest structure will be highly complex. Privatised ownership contributes to the creation of an “iron triangle” consisting of profit-seeking electricity companies, government bureaucrats who sustain nuclear power, and politicians who protect the interests of nuclear power (Vivoda, 2014 Vivoda, V. (2014). Energy security in Japan: Challenges after Fukushima. Surrey: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]; Iguchi & Koga, 2015 Iguchi, M., & Koga, M. (2015). Energy governance in Japan. In S. Mukherjee & D. Chakraborty (Eds.), Environmental challenges and governance: Diverse perspectives from Asia (pp. 219–234). Oxon & London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]). The iron triangle is complicated by the differing motivations of the actors, but it is collective and cooperative in the way that it promotes the interests of the nuclear industry.

Businesses involved in nuclear power try to create new interests by, for example, exporting nuclear plants, fuel and related technology. These new interests mean that nuclear vendors become a new promoter of nuclear power, thus strengthening existing supporters. This allows the nuclear industry to expand and create links with other industries, and in these circumstances, the relevant government agencies are likely to continue to support nuclear power and the advancement of related technology.

Hence, both private ownership of the nuclear power companies and export opportunities in the nuclear industry make nuclear power complex. They make any policy change exceedingly difficult, and any change that does take place is likely to be incremental and marginal in scope. If the interest structure is complex and as a consequence contention is diversified, civil activists must fight on many different fronts. If nuclear power produces new interests – that is, exports – supporters will benefit from uniting to continue to support the existing nuclear power policy, and thus civil activists will grow weary. Conversely, if the interest structure is simple, the activists will fight against a simple target – that is, a pro-nuclear government and a state-owned electricity company working as one body. If the target is solid, the fight may be tough. But if the target is in disarray, any policy change is likely to be drastic and far-reaching.

The second factor, the level of politicisation, addresses the level at which the contention between supporters and civil activism takes place: the national level or the local level. An issue that is politicised at the national level is more controversial than one at the local level, and it attracts broader public attention and triggers a tug of war between the pro- and anti-nuclear camps. The key point of contention is whether the existing nuclear power policy should be maintained or changed. In contrast, any contention that is limited to the local level tends to be issue-specific, involving particular questions such as whether a nuclear power plant or nuclear waste storage facility should be sited in a particular location. Contention normally remains with a locally specific issue, but it may often be elevated to the national agenda. Whether or not activists can seize and act upon such opportunities would decide the fate of the contention. At this stage of being a national agenda, the contention may become entangled in electoral politics, and the form of the alliance between civil activists and political parties becomes a critical factor in policy change.

Once the contention is escalated to and politicised at the national level, it normally securitises the issue of nuclear power in both the administration and the legislature. “Securitisation” means that administrative and legislative actors take up the issue as an existential problem in a given society. The notion of securitisation, which has been used in the study of international relations (Buzan, Wæver, & de Wilde, 1998 Buzan, B., Wæver, O., & de Wilde, J. (1998). Security: A new framework for analysis. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers. [Google Scholar]; Gerard, 2014 Gerard, A. (2014). The securitization of migration and refugee women. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]; Naujoks, 2015 Naujoks, D. (2015). The securitization of dual citizenship: National security concerns and the making of the overseas citizenship of India. Diaspora Studies, 8(1), 18–36.[Taylor & Francis Online], [Google Scholar]), is applicable to the persistent threat caused by both hazardous radiation and the difficulties of relocation, as exemplified by the Fukushima incident. Despite its invisibility, this threat affects people both physically and psychologically. Politicisation of nuclear power at the national level may also be described as securitisation. This means that nuclear power is not just a controversial issue but becomes a nationally significant one. For example, as Prime Minister Naoto Kan said with respect to the Fukushima incident, it would have brought about “a collapse of the nation’s ability to function” if it had been necessary to evacuate the residents of Tokyo (New York Times, 28 May 2015).

In identifying changes to nuclear policy, it is necessary to trace and compare the trajectories of the contention between supporters and challengers of nuclear power – and the combined effects of interest structure and politicisation – after the critical shock. Although this article is an inductive analysis, we attempt, in Figure 1, to summarise the trajectories of the contention in the three cases.

The three cases have undergone changes to varying degrees and in different directions. The Japanese case underwent a striking change – that is, the elevation of contention from local to national level – but it shows the limitations of policy change when dealing with complex interests. As demonstrated by the gradual resumption of operation of the reactors that have undergone safety checks, any drastic policy change, such as the mothballing of entire reactors or exit-from-nuclear, is unlikely to happen in the Japanese case. The Taiwanese case shows a more intense political struggle which was undertaken at the national level and resulted in the highest degree of policy change among the three countries: the freezing of the recently constructed fourth power plant. Furthermore, following the victory of Tsai Ing-wen of the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in the 2016 presidential election, the possibility of decommissioning the existing nuclear plants in the future has become even more likely (Focus Taiwan, 11 March 2016). The Korean case shows the least likelihood of dramatic policy change. Not only does civil activism mostly remain local and issue-specific and seemingly incapable of gearing itself up at the national level, but the industry has created new interest opportunities by exporting four nuclear reactors to the United Arab Emirates. The current progressive administration, which launched in May 2017, has pursued transformation in the energy mix, but has not officially declared that it will cease the export of nuclear plants.

Japan: Elevation of Politicisation but Increasingly Complex Interest Structure

Before Fukushima, nuclear power in Japan was characterised by a complex interest structure and relatively localised civil activism. From the inception of the atomic energy development plan in 1955, nuclear power had diverse promoters with a focused and common goal of expansion and technological advancement, a situation that for a long time disadvantaged anti-nuclear civil activism. The government offered business opportunities in nuclear power to the nine electricity companies, including Tokyo Electric Power Company and Kansai Electric Power Company. The main government organisations – the Japan Science and Technology Agency and the Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI), and its successor the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry (METI) – played decision-making and supervisory roles. In addition, the long years of Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) rule allowed conservative pro-nuclear politicians to exercise powerful influence over local decisions concerning the location of nuclear power plants.

The convergence of interests between the government, electricity companies and politicians, even if they were driven by different motives, made nuclear power a state-sponsored industry (Kim, 2013 Kim, S. C. (2013). Critical juncture and nuclear-power dependence in Japan: A historical institutionalist analysis. Asian Journal of Peacebuilding, 1, 87–108. [Google Scholar]). The government was deeply involved in the expansion of the nuclear industry, and politicians in both Tokyo and the localities were closely engaged in the siting of nuclear power plants. The nine private electricity companies were beneficiaries of the state-sponsored nuclear industry. Just as in other industrial sectors, there emerged a so-called iron triangle made up of politicians, bureaucrats, and the electricity companies (Vivoda, 2014 Vivoda, V. (2014). Energy security in Japan: Challenges after Fukushima. Surrey: Ashgate. [Google Scholar], p. 142; Iguchi & Koga, 2015 Iguchi, M., & Koga, M. (2015). Energy governance in Japan. In S. Mukherjee & D. Chakraborty (Eds.), Environmental challenges and governance: Diverse perspectives from Asia (pp. 219–234). Oxon & London: Routledge. [Google Scholar], p. 227).

Civil activists were disadvantaged by the complex interest structure: diversity of supporters and state sponsorship. Most of their movements were both locally confined and issue specific. Against this backdrop, pro-nuclear supporters were able to achieve the relatively smooth expansion of nuclear-related industries. Furthermore, they succeeded in coopting cash-strapped local governments and residents. The prime movers of the cooptation were electricity companies and conservative LDP politicians, with both groups approaching council members and opinion leaders in the targeted municipalities. The central government also carried out public relations campaigns: placating local opposition through the legislation of subsidies that expedited the construction of new plants and related facilities. The subsidies were basically government funds, although the electricity companies contributed a significant portion of them through their taxes (Nanao, 2011 Nanao, K. (2011). Genbatsu kanryo [Nuclear power bureaucrats]. Tokyo: Soshisha. [Google Scholar], pp. 146–147; Kaneko, 2012 Kaneko, M. (2012). Ishitsuna kukan no keizaigaku: Richi jichitai kara mita genpatsu mondai [Heterogeneous space economics: The problem of nuclear power plants viewed from the hosting local governments]. Sekai, 8, 136–143. [Google Scholar], pp. 136–143). On top of this cooptation, the oil crisis – and the consequent elevation of energy security to a matter of national survival – contributed to sustaining the nuclear industry throughout the 1970s and the first half of the 1980s.

The Chernobyl disaster of 1986 increased public suspicion about the safety of nuclear power, and protests by activists against the construction of nuclear power plants ensued. One notable consequence of this was an increase in the cost of constructing new nuclear power plants and delays in their construction. Civil activists, however, lacked nationwide collaborative networks and thus found it difficult to gain widespread public support (Kim, 2013 Kim, S. C. (2013). Critical juncture and nuclear-power dependence in Japan: A historical institutionalist analysis. Asian Journal of Peacebuilding, 1, 87–108. [Google Scholar], p. 97). The supporters of nuclear power regarded civil activists’ protests as a NIMBY (Not In My Back Yard) phenomenon rather than as a movement aimed at achieving a policy change (Lesbirel, 1998 Lesbirel, H. S. (1998). NIMBY politics in Japan: Energy siting and the management of environmental conflict. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]). It was not until the second half of the 1990s that several accidents in nuclear-related factories began to draw public attention to the safety of nuclear power: a liquid sodium leak at the Monju fast breeder reactor in December 1995; a fire at the Tokaimura reprocessing plant in March 1997; and an accident at the Japan Nuclear Fuel Conversion Co. in September 1999 (Yoshioka, 2011 Yoshioka, H. (2011). Genshiryoku no shakaishi [Social history of nuclear power]. Tokyo: Asahi Shinbun Shuppan. [Google Scholar], pp. 245–362).

To be sure, the Fukushima incident on 11 March 2011 was a critical shock. The incident triggered widespread calls for exit-from-nuclear from activists and the politicisation of the nuclear power issue at the national level. The composition of the participants in civil activism was different from what it had been in the past. Rallies demanding exit-from-nuclear were attended not only by the usual activists but also by housewives, intellectuals, students and middle-class workers. They were joined by anti-nuclear weapons activists who had been mostly silent on the nuclear power issue for decades. This represented a new convergence of Japanese civil activists.

As civil activism has gained momentum, the government’s policy and political discourse have changed to some extent, and a new business interest in alternative energy sources has emerged. First, from September 2013 to August 2015, the government, under public pressure, postponed the resumption of operations of the nuclear power plants that had been shut down for safety checks. Second, keenly aware of the significance of the nuclear safety issue, the government restructured the organisations in charge of safety, establishing a new body, the Nuclear Regulation Authority (NRA), in June 2012. The NRA is an independent organisation, in contrast to the previous nuclear safety watchdog that was part of METI (Ueta, 2014 Ueta, K. (2014). Nihon no enerugi seisaku wa kawattaka [How energy policy is changed in Japan after Fukushima]. Seisaku Kagaku, 21(3), 45–57. [Google Scholar], pp. 45–57). Third, METI led changes in the power system from early 2013 that focused on the liberalisation of the retail market for electricity, although each electricity company still retains its monopoly status (METI, 2013 METI. (2013, February). Denryoku shistemu keikaku senmon iinkai hokokusho [The Report of the Committee on Electricity System Reform]. Retrieved from http://www.meti.go.jp/committee/sougouenergy/sougou/denryoku_system_kaikaku/pdf/report_002_01.pdf %5BGoogle Scholar]; Asahi Shinbun, 11 August 2013). Fourth, electoral candidates from both the ruling LDP and the opposition parties have felt unable to openly support the government’s policy of dependence on nuclear power. For instance, during the election for the Tokyo governor, the LDP-supported candidate, Masuzoe Yoichi, expressed an interest in renewable energy sources, although his commitment remained mostly within the scope of the LDP’s pro-nuclear policy (Mainichi Shinbun, 12 February 2014). Furthermore, in July 2014, Mikazuki Taizo, a Democratic Party candidate who ran an anti-nuclear campaign, was elected governor of Shiga prefecture, which is adjacent to Fukui prefecture, the location of a number of nuclear plants (Japan Times, 15 July 2014). Fifth, some businesses, particularly Softbank under its chairman Son Masayoshi, have begun investing in alternative energy sources, particularly solar power; Son seems keen to exploit the potential synergy effect between information technology and the transmission of smart grid power (Japan Times, 19 April 2012).

Despite the above-mentioned changes on many fronts, the change in public attitude and strengthened civil activism have not been translated into votes for anti-nuclear candidates in most national and local elections. The pro-nuclear LDP was returned to power thanks to a landslide victory in the Lower House election in December 2012. The LDP-led government, having renewed its coalition with the electricity companies, is trying to bring those reactors that have passed safety checks back into operation. As of August 2016, two reactors were operating (Japan Nuclear Safety Institute, 2016 Japan Nuclear Safety Institute. (2016). Licensing status of the Japanese nuclear facilities. Retrieved from http://www.genanshin.jp/english/index.html %5BGoogle Scholar]). In accordance with this line, a report issued by METI on long-term energy policy states that Japan will bring its nuclear power capacity back up to 20–22 per cent of its total electricity output by 2030 (METI, 2015 METI. (2015, July). Long-term energy supply and demand outlook. [Google Scholar], p. 7).

By redoubling its efforts to promote the export of nuclear plants, the Abe cabinet is creating new interests for the nuclear industry, thus increasing the complexity of the interest structure and cancelling out the effects of mushrooming civil activism. Taking advantage of the 2007 US–India Civil Nuclear Agreement (India Review, 1 November 2008, pp. 2–6), Japan had already begun negotiations with India on nuclear energy cooperation in 2010. Yet as soon as it launched, the Abe cabinet newly expanded nuclear cooperation with countries in Southeast Asia (e.g. Vietnam and Indonesia), the Middle East (e.g. Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates), and Eastern Europe (e.g. the Czech Republic, Hungary, Slovakia and Poland) that aspired to possess nuclear power generation capability (Center for Strategic and International Studies, 2014 Center for Strategic and International Studies. (2014, 20 November). Japanese nuclear policy background paper. [Google Scholar]).

At the same time, Japanese nuclear businesses such as Toshiba, Hitachi and Mitsubishi have sought export markets for their products, and their efforts have begun to bear fruit. In one example, a Japanese–French consortium – consisting of Mitsubishi Heavy Industries and AREVA – struck a deal in 2013 to build a nuclear power plant in Turkey. The Japanese government regards the US$22 billion deal as a bridgehead to the nuclear market in the Middle East (BBC News, 3 May 2013). In 2014, Japanese vendors contracted with Lithuania and Bulgaria to build nuclear power plants (Center for Strategic and International Studies, 2014 Center for Strategic and International Studies. (2014, 20 November). Japanese nuclear policy background paper. [Google Scholar], p. 26). It is estimated that any nuclear export contract with India will be worth US$69 billion or more to Japanese vendors (Japan Times, 24 January 2014; Hindustan Times, 13 December 2015). To be sure, the exports would make a major policy shift even more costly. The new export opportunities make the interest structure more complex than it was before the Fukushima incident, a situation that is disadvantageous to those calling for exit-from-nuclear. With the new interests, promoters remain united.

In sum, in the post-Fukushima era, the surge in civil activism succeeded in elevating the level of politicisation of the issue, thus contributing to changes in national policy. In response to the rising tide of anti-nuclear activism, the government strengthened safety regulations and suspended the operation of nuclear plants (except for two reactors, as of August 2016). But civil activism has not been able to break up the coalition between the LDP-led government, conservative politicians and electricity companies since Fukushima. Furthermore, the export of nuclear plants has created new interest opportunities for nuclear vendors, thus contributing to the fundamental maintenance of the nuclear power policy. The Japanese government is unlikely to change its policy drastically, for example by scrapping nuclear power plants completely. Indeed, the government is trying to bring the reactors back into operation as it completes safety checks.

Taiwan: Escalation of Politicisation in a Simple Interest Structure

The Taiwanese case represents a simple interest structure and a high level of politicisation. The simple interest structure, based on state sponsorship, has remained constant since the establishment of Taiwan’s nuclear industry in the 1950s. The issue of nuclear power had already been politicised to a certain extent before Fukushima, and afterwards, in early 2014, fierce contention within and outside the legislature induced the government to decide not to bring the recently completed fourth power plant into operation. It is the existence of politicisation at the national level combined with a simple interest structure that has led to a policy shift away from reliance on nuclear power.

The development of nuclear power in Taiwan has been characterised by a convergence of interests between supporters, including the government, conservative politicians and the state-owned electricity company. The main electricity company, Taiwan Power Company (TaiPower), constructed and operates the nuclear power plants, and has remained state owned. Decades of rule by the conservative Kuomintang (KMT) ensured the establishment and continuation of a pro-nuclear policy direction (Hsu, 1995 Hsu, G. J. Y. (1995). The evolution of Taiwan’s energy policy and energy industry. Journal of Industry Studies, 2(1), 95–109.[Taylor & Francis Online], [Google Scholar]; Hsiao, 1999 Hsiao, H.-H. M. (1999). Environmental movements in Taiwan. In Y.-S. F. Lee & A. Y. So (Eds.), Asia’s environmental movements: Comparative perspectives (pp. 31–54). Armonk, NY: ME Sharpe. [Google Scholar]) and consolidated a network of interests throughout the nuclear industry. Professionals working in or advising the Ministry of Economic Affairs, which regulates the industry, and the Atomic Energy Council under the Executive Yuan, which is in charge of safety inspections, are mostly graduates of the same university department, which also aided the convergence of interests. The Institute of Nuclear Engineering and Science at National Tsinghua University is Taiwan’s only higher education department training nuclear technology specialists.

Taiwan initially wanted to develop nuclear power for military purposes as well, prompted by China’s first nuclear test in 1964 (Central Intelligence Agency, 1972 Central Intelligence Agency. (1972, 1 November). Taipei’s capabilities and intentions regarding nuclear weapons development (Special National Intelligence Estimate). [Google Scholar]). This ambition was soon frustrated by intervention from the United States and the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA). Since then, Taiwan’s pursuit of nuclear technology has been limited to non-military uses (Albright & Gay, 1998 Albright, D., & Gay, C. (1998). Taiwan: Nuclear nightmare averted. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 54(1), 54–60.[Taylor & Francis Online], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar]). Furthermore, in contrast to Japan and Korea, Taiwan has recently made it clear that it has no interest in developing an indigenous uranium enrichment capability (Grossman, 2012 Grossman, E. M. (2012, 19 July). Taiwan ready to forgo nuclear fuel-making in US trade pact renewal. National Journal. Retrieved from http://www.nationaljournal.com/nationalsecurity/taiwan-ready-to-forgo-nuclear-fuel-making-in-u-s-trade-pact-renewal-20120719 %5BGoogle Scholar]). This implies that Taiwan has no intention of developing the nuclear fuel cycle; its only aim is to maintain the existing interest structure of the pro-nuclear camp. This distinguishes the development of the nuclear industry in Taiwan from that in Japan and Korea. Taiwan has a simpler interest structure than the two other countries, because it has a state-controlled electricity company and is not an exporter of nuclear technology.

Anti-nuclear activism in Taiwan has developed while forging close partisan linkages during the struggle for democratisation. By joining forces with the then opposition party, the DPP, the activists helped to politicise the nuclear power issue more than any other environmental issue. On the flip side, civil activists have been unable to make progress when they have failed to obtain DPP backing for their moves (Ho, 2003 Ho, M.-S. (2003). The politics of anti-nuclear protest in Taiwan: A case of party-dependent movement (1980–2000). Modern Asian Studies, 37(3), 683–708.[Crossref], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar]). Anti-nuclear activism experienced a major setback when the DPP came to power in 2000 and failed to deliver on its campaign promise to halt construction of the fourth nuclear power plant. This was because, despite the election of a DPP president, the party held less than one third of the seats in the legislature and therefore could not force through a bill to halt construction of the plant (Wu, 2002 Wu, Y.-S. (2002). Taiwan in 2001: Stalemated on all fronts. Asian Survey, 42(1), 29–38.[Crossref], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar]). Since then, activists have become increasingly disillusioned with party politics (Shih, 2012 Shih, F.-L. (2012). Generating power in Taiwan: Nuclear, political and religious power. Culture and Religion, 13(3), 295–313.[Taylor & Francis Online], [Google Scholar]), and the anti-nuclear issue has not proved particularly attractive to voters, as seen in the 2012 presidential election (interview with activist, Taipei, 15 July 2013). Thus, although at one time it was near the top of the national political agenda, the anti-nuclear cause did not have a significant impact on politics for several decades prior to the Fukushima incident.

The Fukushima incident reignited the national-level contention over the continued use of nuclear power in Taiwan. There was fierce public criticism of the government’s pro-nuclear stance, followed by demands for a radical change in the existing policy. Activists and their supporters have called for a “nuclear-free Taiwan” and demanded that the government scrap the almost-completed fourth nuclear power plant and decommission the other three plants when they reach the end of their scheduled terms (Pingguo Ribao, 10 March 2013). Anti-nuclear activism has attracted more attention across the country than ever before, and its support base has become broader, attracting participation from housewives, celebrities and successful entrepreneurs. Even some KMT politicians, presumably with one eye on the ballot box, have been prompted to show support for anti-nuclear activism (Taipei Times, 27 March 2013). This split in the KMT has been advantageous to the anti-nuclear cause. Meanwhile, experience has taught the activists not to get too close to the DPP, as that would likely discourage non-DPP supporters. Thus, activists have been careful in managing their relations with political parties lest parties and politicians attempt to jump on the anti-nuclear bandwagon (Ho, 2014 Ho, M.-S. (2014). The Fukushima effect: Explaining the resurgence of the anti-nuclear movement in Taiwan. Environmental Politics, 23(6), 965–983.[Taylor & Francis Online], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar]).

As the issue of the continued use of nuclear power became more controversial, the contention moved into the legislature. In early 2013, Premier Jiang Yi-huah proposed a national referendum to decide whether to scrap the fourth nuclear plant. The legislature soon divided into pro- and anti-nuclear camps, and there were skirmishes over when and how the referendum should be implemented. Outside the legislature, the KMT and the relevant government organisations, including the Ministry of Economic Affairs, launched campaigns to persuade people of the economic necessity of the power plant. The DPP offered indirect support to the anti-nuclear activists, and its members delivered speeches at their rallies (interview with activist, Taipei, 30 June 2013). Fierce confrontation continued in the legislature for several months, with no prospect of compromise. When Lee Ching-hua, the KMT legislator who had initiated the referendum proposal, suddenly declared that he would withdraw it, the result was a stalemate (Taiwan News, 10 September 2013).

The deadlock ended when 72-year-old Lin Yi-Hsing, a very important symbol of democratisation and anti-nuclear activism in Taiwan, went on a hunger strike. Lin’s decision to risk his life for the anti-nuclear cause attracted the attention of the public and politicians alike. It soon provoked demonstrations and clashes between anti-nuclear protesters and the police (Taipei Times, 24 April 2014). The escalation of the contention increased the pressure on the Ma Ying-jeou administration. The administration wanted to avoid stirring up more trouble, given that the country had just experienced the Sunflower movement, a civil disobedience campaign on an unprecedented scale. At this time, the government was facing challenges not just from anti-nuclear activists but from society as a whole. Now that escalating protests had crossed partisan lines, the KMT decided that it would freeze the construction of the fourth nuclear power plant as long as there was no shortage of electricity (Pingguo Ribao, 8 September 2014). Even though debate continued over whether the plant should ultimately be scrapped, the move was evidence of meaningful changes in the stance of the Ma administration, as previously the administration had pushed for the fourth power plant to be completed. Additionally, a plan to make the Atomic Energy Council an independent body in charge of nuclear safety has been discussed (Focus Taiwan, 3 January 2014).

The KMT suffered a crushing defeat in the general and presidential elections in early 2016, and in May 2016 the DPP became the ruling party. This change in the political landscape suggests that Taiwan may become even less reliant on nuclear power. Tsai Ing-wen, the new president, has previously proposed a “nuclear free Taiwan”, which would involve decommissioning all nuclear power plants by 2025, exploring alternative energy sources, and pursuing the liberalisation of the electricity industry. It is expected that Tsai will adopt a multi-pronged approach to reducing reliance on nuclear energy, although she will be careful not to stir up massive confusion in the political arena similar to the events of 2000 (Global Issues, 13 January 2016).

The shock of Fukushima seems to have brought about meaningful change in Taiwan. A high level of politicisation and a simple interest structure have been crucial in bringing about such an outcome. Compared to the other two cases, Taiwan has retained an integrated, state-controlled electricity company and has not sought additional sources of income for the nuclear industry. At the same time, anti-nuclear activism has broadened its support base and is pressing forward on two fronts, thus creating a society-wide struggle. By triggering heated debates that cross partisan lines, nuclear power has become a nationally salient political issue. Of the three countries under discussion here, Taiwan is the one that is most likely to undergo drastic and far-reaching change. A sudden national blackout in mid-August 2017 has called into question the feasibility of nuclear phase-out in Taiwan (South China Morning Post, 20 August 2017), but it is unlikely that the hard-won social consensus on nuclear phase-out will easily dissipate.

Korea: Evolving Issue in a Relatively Simple Interest Structure

In Korea, as in Taiwan, the nuclear industry developed within a simple interest structure based on a state-controlled electricity company. The existence of strong links between conservative politicians, bureaucrats and the electricity company emasculated civil activism for several decades. Since Fukushima, Korean civil activism has ridden a tide of rising public awareness of nuclear safety and an increasing unwillingness to accept the construction of nuclear plants and waste storage facilities on their doorstep. Nevertheless, a policy shift is still a long way off: nuclear power remains a local issue, and the creation of new interest opportunities has increased the complexity of the interest structure. Both the government’s “low carbon, green growth” policy introduced in 2008 and its nuclear exports to the United Arab Emirates in 2009 have provided the supporters of nuclear power with new interest opportunities. Consequently the Fukushima effect has remained limited in Korea.

In Korea, both pre- and post-Fukushima, the supporters of nuclear power – especially the government and the government-controlled electricity corporation – have acted almost as a single body, and this simple interest structure has been consolidated over several decades. Under the 1956 Korea–US atomic energy cooperation agreement, Korea started to receive nuclear technology from the United States. Under the junta led by General Park Chung-hee, three private power companies were merged to form the Korean Electric Power Company (KEPCO), the sole state-owned electricity company. Park’s developmental zeal encouraged the growth of the electric power industry in the 1960s, but when, in the mid-1970s, Park tried to introduce fuel cycle technology and related facilities from Canada and France for the purpose of nuclear weapons development, the United States put pressure on Korea to abandon these plans (USNSC, 1975 USNSC. (1975, 28 February). US National Security Council Memorandum, Development of US Policy toward South Korean Development of Nuclear Weapons. History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Retrieved from http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/114627 %5BGoogle Scholar]).

The Korean nuclear power community, rather than being paralysed by the Chernobyl accident in 1986, took advantage of the downturn in its US counterpart, which was desperately seeking a way out of the business slump (Price, 1990 Price, T. (1990). Political electricity: What future for nuclear energy? Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]). KEPCO obtained technology transfers under favourable conditions when it chose a US vendor, Combustion Engineering (CE), to construct its nuclear power plants, Yeongguang 3 and Yeongguang 4 (Lee, 2009 Lee, J.-H. (2009). Hangukui haekjugwon [Korea’s nuclear sovereignty]. Seoul: Gulmadang. [Google Scholar], p. 222). The KEPCO–CE collaboration laid the foundation for the development of indigenous reactor design capability in Korea. During the 1990s and 2000s, Korea succeeded in designing its own standard reactor model APR-1400 (KEPCO, 2014 KEPCO. (2014). Hanguk jollyok sasipnyonsa [The history of forty years of the Korea Electrical Company]. Retrieved from http://www.kepco.co.kr/kepco_plaza/history/index_b.html %5BGoogle Scholar]). Gaining confidence in indigenous technology and reducing its reliance on American knowhow, Korea sought to export its own standard model reactors, signing a contract with the United Arab Emirates in 2009 (Financial Times, 28 December 2009). Korea also continued its efforts, in collaboration with the United States, to develop pyroprocessing, a new technology designed to reduce nuclear waste (Sheen, 2011 Sheen, S. (2011). Nuclear sovereignty versus nuclear security: Renewing the ROK–US Atomic Energy Agreement. Korean Journal of Defense Analysis, 23(2), 273–288.[Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar]; Korea Times, 29 April 2013).

Anti-nuclear activism was relatively slow to develop in Korea. The democratisation of the late 1980s fostered environmental activism, including a certain amount of anti-nuclear activism. But the activists were not able to get the nuclear issue onto the national agenda (Lee, 1999 Lee, S.-H. (1999). Environmental movements in South Korea. In Y.-S. F. Lee & A. Y. So (Eds.), Asia’s environmental movements: Comparative perspectives (pp. 90–119). Armonk, NY: ME Sharpe. [Google Scholar], pp. 92–103). Activists have been able to achieve a certain amount of autonomy in the political realm, but the downside has been that neither of the competing major political parties has taken up the issue of nuclear power in a serious way.

This weak civil activism was the target of cooptation by the pro-nuclear government and KEPCO. Between 1989 and 2005, civil activists – with the support of environmental organisations – seemed to have achieved success in preventing the government from locating nuclear waste storage facilities in economically disadvantaged or remote areas, such as Yeongdeok, Anmyeon-do, Guleop-do and Buan (Kim, 2005 Kim, C.-K. (2005). Banhaek undonggwa jiyokjumin jongchi [Anti-nuclear movement and local politics]. Hanguk sahoe, 6(2), 41–69. [Google Scholar]). In the 2003 Buan case in particular, resistance by civil activists and local residents ended in violence, and the local mayor, Kim Jong-gyu, was injured. The pro-nuclear government and KEPCO’s cooptation strategy overturned that trend in 2005 when they offered US$250 million to any city prepared to host a storage facility for low- and medium-level radioactive waste. Four cities came forward, attracted by the prospect of funds to boost their stagnating economies (Lee, 2009 Lee, J.-H. (2009). Hangukui haekjugwon [Korea’s nuclear sovereignty]. Seoul: Gulmadang. [Google Scholar]). Despite strong protests by civil activists, Kyeongju emerged as the winner after 89.5 per cent of its voters came out in support of the project in a local referendum. The issue of where to locate radioactive waste storage facilities, by its very nature, was unable to attract national attention or prompt joint resistance. The central government collaborated with cash-strapped local governments in order to divide the local population (Yun, 2006 Yun, S.-J. (2006). 2005nyon jung-jeojuwi bangsasong pegimul chobunsiseol chujin gwajonggwa banhaekundong [The process of siting medium- and high-level radioactive waste storage and the anti-nuclear movement, 2005]. Siminsahoewa NGO, 4(1), 277–311. [Google Scholar]). Cooptation in the guise of the “democratic process” justified and empowered the government in its plans. It also further incapacitated anti-nuclear activism in Korea. In this context, it is not surprising that the Korean government, particularly the previous Lee administration and the incumbent Park administration, is not committed to reducing reliance on nuclear power (New York Times, 4 August 2013; Hankyoreh, 15 January 2014).

Owing to the critical shock of the Fukushima incident, the government has had to pay more attention to nuclear safety. When Korea hosted the Nuclear Security Summit in March 2012, the then president, Lee Myung-bak, stressed the link between nuclear security and safety. This new concern was timely in view of the ramifications of Fukushima. In the same context, the Lee administration separated the Nuclear Security and Safety Commission from the Ministry of Education, Science, and Technology in October 2012, making it an independent body.

Amid heightened concerns about nuclear safety, revelations about a bribery scandal in the nuclear power business in 2013 gave new impetus to anti-nuclear activists, although action was slow to develop and was local in scope. First of all, the country’s four religious groups – Protestant, Catholic, Buddhist and Won Buddhist – adopted an exit-from-nuclear stance, and more than 40 anti-nuclear civic organisations came together in a loose but extended umbrella organisation, Collective Action for a Nuclear-free Society. Second, local politics in a few cities has begun to reflect concerns about the country’s excessive reliance on nuclear power. At the local elections held in June 2014, a candidate who opposed the government’s plan to construct a new power plant was elected in Samcheok, and a politician who opposed extending the life of the oldest plant at Gori was elected in Busan. In a local poll held in Yeongdeok in August 2015, 62 per cent of voters opposed the construction of two new nuclear plants (Dalton & Cha, 2016 Dalton, T., and Cha, M. (2016, 23 February). South Korea’s nuclear energy future. The Diplomat. Retrieved from http://thediplomat.com/2016/02/south-koreas-nuclear-energy-future/ %5BGoogle Scholar]). The city government of Seoul has adopted a policy of gradually reducing energy consumption and facilitating the generation of renewable energy, with the aim of transforming the city from a consumer to a producer of energy. With the support of ardent activists, Mayor Park Won-soon has led the “one fewer nuclear power plant” drive since 2012 (interview with activist, Seoul, 31 July 2014).

As far as the activists are concerned, the contention in general remains local; that is, the most problematic issues are the safety concerns of local residents and their unwillingness to accept nuclear power. The trend towards declining local acceptance, as seen in Samcheok, Yeongdeok and Busan in recent years, certainly raises the cost of construction of both nuclear power plants and nuclear waste dumps, but the candidate sites for nuclear power plants are located far from the capital and other cities that are benefiting from nuclear-powered electricity. Civil activism, despite its gradual expansion due to localised opposition to nuclear facilities, is still weak. Its nationwide network is only loosely integrated, compared to the solid interest structure of the nuclear supporters.

There are two factors that bolster the solidarity of the supporters of nuclear power in Korea. The first is the government’s pursuit since August 2008 of a “low carbon, green growth” policy, in which nuclear power continues to have a significant role. This policy, which was adopted under President Lee, has continued under the present administration. Indeed, the Seventh Basic Plan for Electricity Demand and Supply states that 28.2 per cent of Korea’s total electricity should be generated by nuclear power by 2029 – which is similar to the 2014 level of 30.0 per cent. In order to meet the increasing demand for electricity, the government plans to build two more reactors (Ministry of Trade, Industry, and Energy, 2015 Ministry of Trade, Industry, and Energy. (2015). 7cha jeonryeok sugeup gibongyeohweok, 2015–2029 [The Seventh Basic Plan of Electricity Demand and Supply, 2015–2029]. [Google Scholar], p. 4, p. 8).

The second factor that favours the solidarity of the promoters of nuclear power is the rise of new interests, especially the export of nuclear power plants, which is solidifying the policy on nuclear power. With strong government support, in 2009 Korea succeeded in winning a contract with the United Arab Emirates to build four reactors worth US$20.4 billion. This has strengthened the ties between stakeholders (Wall Street Journal, 28 December 2009). As a competitor of Japanese and French manufacturers, the Korean vendor is also seeking new opportunities in other countries in the Middle East, Southeast Asia and Eastern Europe. It is unlikely that this solid interest structure, which has also become more complex than before, will be shaken to any significant degree in the near future.

With the launch of the new administration in May 2017, and particularly with President Moon Jae-in’s personal preference for the gradual phasing-out of nuclear power, Korea’s policy today is different from the previous administration’s reliance on nuclear power. The Moon administration has tried to ratchet up public support for its policy by facilitating debates in a public-opinion committee with regard to the issue of stopping or continuing the construction of two new nuclear reactors at Sin-gori. Yet the public-opinion committee produced a contradictory result: support for the continuation of the construction of the reactors at Sin-gori and simultaneous support for a gradual reduction of nuclear power domestically (Jang, 2017 Jang, S. Y. (2017, 26 October). South Korea’s nuclear energy debate. The Diplomat. Retrieved from https://thediplomat.com/2017/10/south-koreas-nuclear-energy-debate/ %5BGoogle Scholar]). The Moon administration has committed to implementing the committee’s recommendations, and has reconfirmed its policy priority regarding the gradual phasing-out of nuclear power. What should be noted here is that, unlike its domestic nuclear policy, the administration has not declared its firm intention to reject the possibility of exporting nuclear plants. This inconsistent position has sparked criticism from the opposition party, which has claimed that no country will buy Korean nuclear power plants if the Moon administration is reducing the use of nuclear power domestically. Given this situation, it seems that Korea’s underlying reliance on nuclear power is unlikely to undergo a dramatic change.

Generalisations about the Contention over Nuclear Power and Likely Policy Changes

Any major change to a government’s nuclear power policy is most likely brought about by contention between pro- and anti-nuclear forces. Specifically, change is determined by the combined effect of the interest structure and the level of politicisation. By examining these two factors, we are able to establish some generalisations regarding the conditions under which the challengers (i.e. civil activists) are able to contribute to a significant change in nuclear power policy.

In relation to the interest structure, the analysis in this article leads us to the following generalisation: civil activism is less likely to bring about policy change if it has to compete with diverse supporters of nuclear power than with a monolithic supporter. In a complex environment, activists are besieged by different supporters of nuclear power, including the government, electricity companies and politicians. Activists need to contest the government’s energy policy, demonstrate against the siting of nuclear plants, monitor electricity companies’ safety measures, and keep a vigilant eye on the triangular relationship between supporters. Anti-nuclear activism is, by its very nature, constrained by the supporters of nuclear power who act as veto players against policy change. The way in which the complex nature of the defenders (who in this case are the supporters of nuclear power) diffuses the effect of the challenger’s strategy (the challenger here being civil activist groups) is not unique to the case of nuclear power, but analogous to opposing alliances in international relations (e.g. Christensen, 2011 Christensen, T. J. (2011) Worse than a monolith: Alliance politics and problems of coercive diplomacy in Asia. Princeton: Princeton University Press.[Crossref], [Google Scholar]). The supporters of nuclear power tend to coalesce, even if they have different reasons for supporting nuclear power as an essential energy source; dealing with this complexity exhausts civil activism. Furthermore, the export of nuclear power plants creates additional supporters: reactor vendors, nuclear fuel makers and technologists. Therefore, unless the complex interest structure breaks up, the politicisation of the nuclear power issue at the national level will not by itself bring about any major policy change. The Japanese case demonstrates this very well.

We can also make a generalisation concerning politicisation: if civil activism manages to exert pressure on both the pro- and anti-nuclear political camps, a drastic and far-reaching policy change is likely to occur. Politicisation at the national level is a kind of securitisation of the nuclear power issue. Calls for exit-from-nuclear at a national level involve the dissemination by activists of information regarding the hazardous contamination of water and air, and the effects of radiation on children’s health and the mental health of evacuees, and so on. All these activities are aimed at securitising the issue among both the public and politicians and political parties. In order to be successful, civil activists must act strategically, making sure that the issue is a salient campaign agenda item for both the ruling and opposition parties. Civil activism should not rely on one particular party. Although reliance on one party may allow activists to take advantage of that party’s organisational resources, it can mean that they become the instruments of the party (Ho, 2003 Ho, M.-S. (2003). The politics of anti-nuclear protest in Taiwan: A case of party-dependent movement (1980–2000). Modern Asian Studies, 37(3), 683–708.[Crossref], [Web of Science ®], [Google Scholar]). Alignment with a particular party will lead to a policy shift only if that party wins a presidential election and holds a majority in the legislature. Thus, a more viable strategy for activists is to work on both the ruling and opposition parties, thus turning nuclear power into a nonpartisan, securitised national issue.

The comparisons we have drawn in this article, and generalisations that are based on them, provide us with a balanced understanding of both the structural constraints on actors in the contention over nuclear power and the process in which each actor manoeuvres. This balanced understanding has significant implications for anti-nuclear activists all over the world with regard to their choice of strategy: in order to achieve their aims, they need to politicise and securitise the issue of nuclear power at the national level, while at the same time crossing the partisan line and putting pressure on both pro- and anti-nuclear political parties. The Taiwanese case demonstrates this model. Activists have benefited from the simple interest structure and the resultant single battlefront (i.e. activists vs the government); furthermore, they have enhanced their ability to cross the partisan line to press both the ruling and opposition parties to support exit-from-nuclear. Additionally, the change in the political landscape brought about by the DPP’s victory in the January 2016 presidential election has improved the prospects for further policy change (e.g. the decommissioning of old plants and a halt to the construction of new ones).

The analysis in this article helps us to address the question of why anti-nuclear activism produces different outcomes in different countries. A diversified, complex interest structure produces a threshold, if not a fault-line, that makes significant policy change exceedingly difficult, even when the nuclear power issue is highly politicised. For civil activism, it is not a matter of choosing whether to confront a complex or a simple interest structure, as the interest structure is already in place. The activists’ cause may be helped by a combination of heightened public awareness, collaboration with the political leadership, and the commercial development of alternative energy sources.

Conclusion

The Fukushima incident has certainly energised civil activism in all three countries under consideration in this article, and in all three cases it has led to calls for exit-from-nuclear, to varying degrees. The incident has served to securitise the political discourse regarding nuclear power and has laid the foundation for the adoption of a modified energy policy, but these changes do not mean the end of nuclear power in these three countries: they mean different things in each of the three cases.

This article has demonstrated the combined effect of interest structure and level of politicisation on the scope of policy change. Interest structure is more historically dependent than the level of politicisation. The complexity or simplicity of the interest structure is related to the industrial development pattern at the time of the introduction of nuclear power and the export structure of the key industries, including nuclear power, at the advanced stage of industrial development. In contrast, the level of politicisation is something that civil activism is able to manipulate at the time of a critical shock, such as the Fukushima incident.

By tracing the trajectories of contention over nuclear power policy, this article finds that the scope of policy change is greatest in Taiwan, followed by Japan and then Korea. The Taiwanese case has a simple interest structure, so politicisation at the national level and civil activism’s crossing of the partisan line make significant policy change more likely. Because of the complex interest structure and new interest opportunities stemming from the export of nuclear plants, the Japanese case, despite strengthened nationwide civil activism, is likely to see pro-nuclear forces regain a certain degree of momentum in the long run. We also find that Korea is the least likely of the three to undergo a policy change, although civil activism there is slowly expanding.

We have learned two lessons from the above analysis that may be relevant for anti-nuclear civil activism: first, a complex interest structure presents a more formidable obstacle to civil activists than a simple, monolithic one; second, if civil activism manages to exert pressure on both the pro- and anti-nuclear political camps at a critical moment, a drastic and far-reaching policy change is likely to occur.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Funding

This work was supported by a National Research Foundation of Korea Grant funded by the Korean Government (NRF-2010-361-A00017) and the Hankuk University of Foreign Studies Research Fund.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their deep gratitude to Nathan Batto, Stephan Haggard, Ming-sho Ho, Nae-Young Lee, Taedong Lee, Tse-Kang Leng, Takemoto Makiko and Hungwen Tseng for their insightful comments and suggestions. The authors also thank the three reviewers for their critical, helpful comments for the improvement of this paper.

References

Albright, D., & Gay, C. (1998). Taiwan: Nuclear nightmare averted. Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 54(1), 54–60.

[Taylor & Francis Online], [Web of Science ®]

Asahi Shinbun. (2013, 11 August). Denryoku jiyuka: Honto no kyoso no tameniwa [Liberalisation of electricity: To make it really competitive].

BBC News. (2013, 3 May). Japan signs Turkey nuclear deal.

Bullard, M. (2005, 1 May). Taiwan and nonproliferation. Nuclear Threat Initiative. Retrieved from http://www.nti.org/analysis/articles/taiwan-and-nonproliferation/

Buzan, B., Wæver, O., & de Wilde, J. (1998). Security: A new framework for analysis. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Center for Strategic and International Studies. (2014, 20 November). Japanese nuclear policy background paper.

Central Intelligence Agency. (1972, 1 November). Taipei’s capabilities and intentions regarding nuclear weapons development (Special National Intelligence Estimate).

Christensen, T. J. (2011) Worse than a monolith: Alliance politics and problems of coercive diplomacy in Asia. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

[Crossref]

Dalton, T., and Cha, M. (2016, 23 February). South Korea’s nuclear energy future. The Diplomat. Retrieved from http://thediplomat.com/2016/02/south-koreas-nuclear-energy-future/

Fam, S. D., Xiong, J., Xiong, G., Yong, D. L., & Ng, D. (2014). Post-Fukushima Japan: The continuing nuclear controversy. Energy Policy, 68, 199–205.

[Crossref], [Web of Science ®]

Financial Times. (2009, 28 December). South Korea wins $20bn UAE nuclear power deal.

Focus Taiwan. (2014, 3 January). Xuezhe: Yuannenghui yinggaiwei heguanhui [Scholar: Atomic Energy Council should be changed to Nuclear Safety Committee].

Focus Taiwan. (2016, 11 March). DPP to move toward “Nuclear Free Homeland” in 2025.

Gerard, A. (2014). The securitization of migration and refugee women. New York: Routledge.

Global Issues. (2016, 13 January). Polls harken end of nuclear power. Retrieved from http://www.globalissues.org/news/2016/01/13/21753

Golay, M. W. (2001). On social acceptance of nuclear power. The Center for International Political Economy & the James A. Baker III Institute for Public Policy, Rice University.

Grossman, E. M. (2012, 19 July). Taiwan ready to forgo nuclear fuel-making in US trade pact renewal. National Journal. Retrieved from http://www.nationaljournal.com/nationalsecurity/taiwan-ready-to-forgo-nuclear-fuel-making-in-u-s-trade-pact-renewal-20120719

Hankyoreh. (2014, 15 January). Government plan confirms move toward greater reliance on nuclear power.

Hindustan Times. (2015, 13 December). India, Japan fast-track ties with bullet train, civil nuclear deal. Retrieved from http://www.hindustantimes.com/india/india-japan-ink-mou-on-civil-nuclear-energy-bullet-train/story-mKen9n93PKaGv85oeSmiwM.html

Ho, M.-S. (2003). The politics of anti-nuclear protest in Taiwan: A case of party-dependent movement (1980–2000). Modern Asian Studies, 37(3), 683–708.

[Crossref], [Web of Science ®]

Ho, M.-S. (2014). The Fukushima effect: Explaining the resurgence of the anti-nuclear movement in Taiwan. Environmental Politics, 23(6), 965–983.

[Taylor & Francis Online], [Web of Science ®]

Hsiao, H.-H. M. (1999). Environmental movements in Taiwan. In Y.-S. F. Lee & A. Y. So (Eds.), Asia’s environmental movements: Comparative perspectives (pp. 31–54). Armonk, NY: ME Sharpe.

Hsu, G. J. Y. (1995). The evolution of Taiwan’s energy policy and energy industry. Journal of Industry Studies, 2(1), 95–109.

[Taylor & Francis Online]

Iguchi, M., & Koga, M. (2015). Energy governance in Japan. In S. Mukherjee & D. Chakraborty (Eds.), Environmental challenges and governance: Diverse perspectives from Asia (pp. 219–234). Oxon & London: Routledge.

India Review. (2008, 1 November). India, United States sign historic civil nuclear agreement.

Jang, S. Y. (2017, 26 October). South Korea’s nuclear energy debate. The Diplomat. Retrieved from https://thediplomat.com/2017/10/south-koreas-nuclear-energy-debate/

Japan Nuclear Safety Institute. (2016). Licensing status of the Japanese nuclear facilities. Retrieved from http://www.genanshin.jp/english/index.html

Japan Times. (2012, 19 April). Firms angling for slice of green energy pie.

Japan Times. (2014, 24 January). Abe-genda: Nuclear export superpower.

Japan Times. (2014, 15 July). The blowback from Shiga. Editorial.

Kaneko, M. (2012). Ishitsuna kukan no keizaigaku: Richi jichitai kara mita genpatsu mondai [Heterogeneous space economics: The problem of nuclear power plants viewed from the hosting local governments]. Sekai, 8, 136–143.

KEPCO. (2014). Hanguk jollyok sasipnyonsa [The history of forty years of the Korea Electrical Company]. Retrieved from http://www.kepco.co.kr/kepco_plaza/history/index_b.html

Kido, A. (1998). Trends of nuclear power development in Asia. Energy Policy, 26(7), 577–582.

[Crossref], [Web of Science ®]

Kim, C.-K. (2005). Banhaek undonggwa jiyokjumin jongchi [Anti-nuclear movement and local politics]. Hanguk sahoe, 6(2), 41–69.

Kim, S. C. (2013). Critical juncture and nuclear-power dependence in Japan: A historical institutionalist analysis. Asian Journal of Peacebuilding, 1, 87–108.

Kim, Y., Kim, M., & Kim, W. (2013). Effect of the Fukushima nuclear disaster on global public acceptance. Energy Policy, 61, 822–828.

[Crossref], [Web of Science ®]

Korea Times. (2013, 29 April). Korea–US Atomic Energy Agreement. Retrieved from http://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/news/opinon/2013/10/305_134801.html

Lee, J.-H. (2009). Hangukui haekjugwon [Korea’s nuclear sovereignty]. Seoul: Gulmadang.

Lee, S.-H. (1999). Environmental movements in South Korea. In Y.-S. F. Lee & A. Y. So (Eds.), Asia’s environmental movements: Comparative perspectives (pp. 90–119). Armonk, NY: ME Sharpe.

Lesbirel, H. S. (1998). NIMBY politics in Japan: Energy siting and the management of environmental conflict. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Mainichi Shinbun. (2014, 12 February). Tochiji ni Masuzoesi, genpatsuronsen kongo ni ikase [Mr Masuzoe, elected Tokyo Governor, should make the debate on the nuclear power alive afterwards]. Editorial.

Medhurst, M. J. (1997). Atoms for peace and nuclear hegemony: The rhetorical structure of a Cold War campaign. Armed Forces and Society, 23(1), 571–593.

[Crossref]

METI. (2013, February). Denryoku shistemu keikaku senmon iinkai hokokusho [The Report of the Committee on Electricity System Reform]. Retrieved from http://www.meti.go.jp/committee/sougouenergy/sougou/denryoku_system_kaikaku/pdf/report_002_01.pdf

METI. (2015, July). Long-term energy supply and demand outlook.

Ministry of Trade, Industry, and Energy. (2015). 7cha jeonryeok sugeup gibongyeohweok, 2015–2029 [The Seventh Basic Plan of Electricity Demand and Supply, 2015–2029].

Nanao, K. (2011). Genbatsu kanryo [Nuclear power bureaucrats]. Tokyo: Soshisha.

Naujoks, D. (2015). The securitization of dual citizenship: National security concerns and the making of the overseas citizenship of India. Diaspora Studies, 8(1), 18–36.

[Taylor & Francis Online]

New York Times. (2013, 4 August). Scandal in South Korea over nuclear revelations.

New York Times. (2015, 28 May). Japan’s former leader condemns nuclear power.

Nohrstedt, D. (2005). External shocks and policy change: Three Mile Island and Swedish nuclear energy policy. Journal of European Public Policy, 12(6), 1041–1059.

[Taylor & Francis Online], [Web of Science ®]

Park, E., & Ohm, J. Y. (2014). Factors influencing the public intention to use renewable energy technologies in South Korea: Effects of the Fukushima nuclear accident. Energy Policy, 65, 198–211.