Contaminated water at nuclear plant still an issue ahead of Tokyo Olympics

March 10, 2020

Work to deal with contaminated water at Japan’s Fukushima nuclear power plant continues as the Olympic Games approach.

Inside a giant decontamination facility at the destroyed plant, workers in hazmat suits monitor radioactive water pumped from three damaged reactors.

The decontamination process is a key element of a contentious debate over what should be done with the nearly 1.2 million tons of still-radioactive water being closely watched by governments and organisations around the world ahead of this summer’s Tokyo Olympics.

The plant’s operator, Tokyo Electric Power Company, or Tepco, says it needs to free up space as work to decommission the damaged reactors approaches a critical phase.

It is widely expected that Tepco will gradually release the water into the nearby ocean following a government decision allowing it to do so.

Work on Fukushima plant, halted during 2016 G7 summit, to continue during Tokyo Olympics

Workers are seen near storage tanks for radioactive water at Tokyo Electric Power Co’s (TEPCO) tsunami-crippled Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant in Okuma town, Fukushima prefecture, Japan January 15, 2020. Picture taken January 15, 2020

Workers are seen near storage tanks for radioactive water at Tokyo Electric Power Co’s (TEPCO) tsunami-crippled Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant in Okuma town, Fukushima prefecture, Japan January 15, 2020. Picture taken January 15, 2020

March 4, 2020

TOKYO (Reuters) – Decommissioning work at Japan’s crippled Fukushima nuclear power station, halted during a G7 summit in Japan in 2016, will not stop during this summer’s Tokyo Olympics, the plant operator said.

There are about a third fewer workers now – 4,000 compared with 6,000 in 2016 – which makes the decision to keep working easier, said Akira Ono, Tokyo Electric Power Co’s (Tepco) chief decommissioning officer.

“When I was the plant manager, I suspended operations at the time of the Ise-Shima summit. But the situation is totally different now,” Ono told Reuters in an interview.

Although the coronavirus outbreak – which has sickened more than 1,000 Japanese – has disrupted supply chains, there has been no shortage of protective gear at the plant, he added. Workers must wear special clothing to protect them from residual radiation in some parts of the facility.

“There was a time when coverall supply became quite tight … But after talking with various sources, we are now sure that we can procure what we need,” Ono said in the interview conducted on Tuesday but embargoed till Wednesday.

A powerful earthquake and tsunami hit eastern Japan in March 2011 and knocked out cooling systems at Tepco’s Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant, triggering the worst nuclear accident since Chernobyl in 1986.

Since then, the operator has been working to clean up the damage and contain any spread of radiation.

For the last nine years, Tepco has been pouring water over melted reactor cores to keep them cool. Nearly 1.2 million tonnes of tainted water, enough to fill 480 Olympic-sized swimming pools, is stored at the plant. The company treats the water to remove most radioactive material.

A government panel reviewing potential disposal methods has recommended releasing the water into the sea after dilution. Local residents, fishermen in particular, strongly oppose the ocean discharge.

Ono said that the plant will likely run out of tank space by summer 2022.

“The time is getting near,” Ono said, referring to a decision on the disposal method. “We are cutting it very close.”

Japanese trade and industry minister Hiroshi Kajiyama said last month the government would decide after hearing opinions from people in local communities and others, without committing to a deadline.

Poll: 57% oppose dumping water into ocean from Fukushima plant

Tanks storing contaminated water occupy the site of the Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant in Okuma, Fukushima Prefecture, in August 2019.

Tanks storing contaminated water occupy the site of the Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant in Okuma, Fukushima Prefecture, in August 2019.

February 28, 2020

Fifty-seven percent of respondents to a poll in Fukushima Prefecture say they oppose the government’s plan to release tons of contaminated water from the Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant into the ocean.

In the survey, conducted by The Asahi Shimbun and Fukushima Broadcasting Co. on Feb. 22-23, 31 percent supported the plan.

About 1.2 million tons of water contaminated with radioactive substances are in storage tanks at the crippled plant, operated by Tokyo Electric Power Co.

The government plans to remove most of the radioactive substances from the water and release the diluted portion into the ocean.

Among male respondents, 35 percent said they support the plan, compared to 26 percent of female respondents who also agreed.

Respondents who are in their 40s are most likely to support the plan, as 41 percent back the plan.

However, more respondents opposed the plan in every age group.

Asked about damage caused by harmful rumors surrounding the release of the contaminated water, 89 percent of the respondents said they were “very much” or “somewhat” concerned.

Even among those who supported the plan, 79 percent said they were worried about the possible damage.

Only 23 percent said they approved of the central government and TEPCO’s handling of the contaminated water problem. That was up from 14 percent in last year’s survey.

Still, 57 percent of the respondents said they did not approve of the handling of the contaminated water.

The government has committed to disposing of waste substances, including contaminated soil removed in the decontamination work, within 30 years and locating a final waste disposal site outside of Fukushima Prefecture.

“We will do our best to keep the promise,” Environment Minister Shinjiro Koizumi has pledged.

Asked if the promise will be kept, 80 percent of the respondents said they did not think so “at all” or “very much.”

Only 17 percent said they thought the government will keep the promise “very much” or “somewhat.”

Fukushima Prefecture will be the starting point of the months-long nationwide torch relay for the 2020 Tokyo Games.

Asked if the relay will contribute to showing the public the current state of the disaster-stricken area, 41 percent said it would, while 51 percent said it would not.

In other questions, 69 percent opposed resuming operations of nuclear power plants that have been idle since the Fukushima nuclear accident, while 11 percent supported it.

In a nationwide survey conducted by The Asahi Shimbun on Feb. 15 and 16, 56 percent opposed the resumption, while 29 percent supported it.

The two media companies have conducted a phone survey of eligible voters in Fukushima Prefecture since the 2011 Great East Japan earthquake, tsunami and nuclear disaster. The recent survey was the 10th.

Landline phone numbers were randomly selected by computer and then called by survey staff. Of these, 1,883 belonged to eligible voters. The survey received a total of 1,035 effective responses with the response rate at 55 percent.

IAEA chief says Fukushima water release plan meets global standards

IAEA Director General Rafael Grossi inspects the Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant on Wednesday.

IAEA Director General Rafael Grossi inspects the Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant on Wednesday.

February 27, 2020

OKUMA, FUKUSHIMA PREF. – The head of the International Atomic Energy Agency said Wednesday that Japan’s plan to release radioactive water from the Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant into the environment meets global standards for the industry.

The comment by IAEA Director General Rafael Grossi, made during a tour of the facility that was devastated by the powerful earthquake and tsunami in 2011, comes amid strong opposition to the plan from local fishermen and neighboring South Korea.

“Whatever way forward must be based on a scientific process, a process which is based on a scientifically based and proven methodology,” Grossi told reporters after the tour.

“It is obvious that any methodology can be criticized. What we are saying from a technical point of view is that this process is in line with international practice,” he said.

This is a common way to release water at nuclear power plants across the globe, even when they are not in emergency situations, he said.

The government and Tokyo Electric Power Company Holdings Inc., the operator of the crippled complex, are considering ways to safely dispose of the more than 1 million tons of water contaminated with radioactive materials after being used to cool the melted fuel cores at the plant, which straddles the towns of Okuma and Futaba.

The water, which is increasing at a pace of about 170 tons a day, is being treated using an advanced liquid processing system (ALPS) to remove most contaminants other than the relatively nontoxic tritium. The water is being stored in tanks on the facility’s premises but space is expected to run out by summer 2022.

Methods being discussed include releasing the water into the Pacific Ocean or allowing it to evaporate, both of which the government says will have minimal effect on human health.

But local fishermen have voiced strong opposition to such plans for fear that Japanese consumers would shun seafood caught nearby. South Korea, which currently bans imports of seafood from the area, has also repeatedly voiced concerns about the environmental impact.

Grossi, an Argentine diplomat who succeeded the late Yukiya Amano as IAEA director general in December, said the Vienna-based organization is prepared to help put the international community at ease.

“What the IAEA can do, at the request of Japan, is to provide support, advice when the process starts. This can take different forms, for example we can assist in the monitoring of the water previous to its controlled release into the environment,” Grossi said.

In a speech to Tepco employees at the plant, Grossi voiced appreciation for their hard work on the decommissioning process, which is scheduled to end 30 to 40 years after the disaster.

“It’s a job of decommissioning but it’s (also) a job of reconstruction,” he said.

Grossi, who is on a five-day trip to Japan, also met with Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and Foreign Minister Toshimitsu Motegi on Tuesday.

On Thursday, Grossi told reporters in Tokyo that Japan should be flexible on its timeline for removing melted fuel from the wreckage of the Fukushima plant, with safety being the top priority.

The government and Tepco currently plan to begin extracting the highly radioactive debris by the end of 2021, though the process is expected to be fraught with technical challenges.

“The issue of the timing is always important … but it’s not a race against time. It is a race, I would say, more against safety. And more safety, this is what is very important,” he said.

https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2020/02/27/national/iaea-chief-fukushima-water/#.XlgKY0pCeUk

An Olympic-Sized Disaster Is Brewing in Japan

Tokyo Electric Power Company demonstrates how to measure radiation of water processed in ALPS II (Multi-nuclide retrieval equipment) at the tsunami-devastated nuclear power plant, Fukushima, January 22, 2020.

Tokyo Electric Power Company demonstrates how to measure radiation of water processed in ALPS II (Multi-nuclide retrieval equipment) at the tsunami-devastated nuclear power plant, Fukushima, January 22, 2020.

February 24, 2020

The 2020 Summer Olympics are coming to Japan — despite two major health scares: radiation from the nuclear meltdown at Fukushima and, more recently, the coronavirus. Over half of the coronavirus cases outside of China were onboard a cruise ship docked in Japan. (On board, 634 cases; on land, another 93, but these figures constantly change.)

The Japanese government is handling the coronavirus outbreak much the same way China handled it: not by controlling the situation, but by controlling information about the situation.

And this is the same way the Japanese government is handling the Fukushima crisis. Prime Minister Shinzo Abe told the Olympic Committee that the nuclear meltdowns at Fukushima are not a problem.

“Let me assure you, the situation is under control,” he said in 2013.

That was a lie — one that let Olympic planning proceed by virtue of official denial of nuclear uncertainty with lethal potential.

And now the Olympics may also be threatened by a health crisis of another sort: Japan’s botched handling of the coronavirus.

Japan’s official response to this new threat has already drawn criticism, especially for releasing hundreds of possibly exposed passengers from a cruise ship into the general population. The dysfunction of Japan’s response to this crisis is illustrated by the fact that its environment minister skipped a government meeting on the coronavirus outbreak in favor of a political celebration in his home town. The Bangkok Post argues that time is running out on the Tokyo Olympics:

Japan needs to rethink the Olympics. The most pressing reason to postpone or cancel the 2020 Tokyo summer games, which are due to start in late July, is a raging public health crisis of unknown dimensions. The second most important reason to put the Olympics on hold is the Japanese government response to the public health crisis to date: it has shown itself to have feet of clay.

At the same time, organizers of the Tokyo marathon on March 1 have limited participation to about 200 athletes, after originally expecting 38,000.

Meanwhile, the governor of Fukushima Prefecture was reassuring the public that radiation is no threat to the safety of the Olympic torch run on March 26: “Through this ‘Reconstruction Olympics,’ we would like to show how Fukushima’s reconstruction has progressed in the past nine years as the result of efforts in cooperation with the Japanese government.”

“Using Greenpeace’s calculations, people staying near the stadium could be exposed to a greater amount of radiation in just over a day than they would naturally experience in a year.”

There is no way to know how the coronavirus spread will play or what effect, if any, it will have on the Summer Olympics. But it’s clear that the Japanese government has a huge stake in minimizing the perceived threat, exercising a level of denial that mirrors the official reassurances about Fukushima over the past nine years.

Judging by the head of the Australian Olympic Committee’s response, the Japanese reassurances are being taken at face value, albeit with significant caveats:

They’ve made it quite clear to us that there is no case for postponing, cancelling the Games at all … provided that all of the requirements of the Japanese authority on people coming into the Games are followed … We’re very satisfied that all the checks and balances will be there by the time the athletes and the spectators enter the country.

Although the Tokyo Olympics committee tells everyone that none of the Olympic playing fields are radioactive, there have been reports to the contrary near Fukushima. South Korean athletes plan to bring their own food and radiation detectors. (Australian and US athletes will eat Japanese-prepared meals.)

The Hot Spots

The J-Village National Training Center is an Olympic sports complex that includes a stadium, 11 soccer fields, a swimming pool, a hotel, and conference center — all located about 12 miles from the ruined reactors at Fukushima.

Last December, the environmental organization Greenpeace published a study documenting radioactive hot spots at J-Village, and found in some areas radiation levels as much as 1,700 times higher than they had been in 2011 before the meltdowns.

Greenpeace also found radiation levels roughly 280 times higher than those promised by the Japanese government. As CNN reported: “Using Greenpeace’s calculations, people staying near the stadium could be exposed to a greater amount of radiation in just over a day than they would naturally experience in a year.”

While Greenpeace found that most of the J-Village site was not highly radioactive, the organization questioned the Tokyo Electric Power Co.’s (TEPCO) approach to cleaning up the hot spots at the site:

How were such high levels of radiation not detected during the earlier decontamination by TEPCO? Why were only the most alarming hotspots removed and not the wider areas following the standard decontamination procedures? Given these apparent failures, the ability of the authorities to accurately and consistently identify radiation hot spots appears to be seriously in doubt.

On January 21, Fukushima Prefecture officials issued a statement assuring the public that radiation levels “won’t be posing any problem for holding the torch relay,” and that radiation exposure would be less than the exposure during a flight from New York to Tokyo.

The statement provided no details explaining any ongoing safety measures: what measures had been taken to decontaminate hot spots, what effort was being made to search out other hotspots, or any other details of decontamination procedures.

A Disaster in Slow Motion

The 2011 nuclear meltdowns at Fukushima may now be widely ignored or forgotten, but the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant remains an evolving, multi-faceted disaster proceeding in slow motion. Radiation is constantly leaking from the nuclear complex where three melted nuclear cores remain a threat should they lose the water that keeps the meltdowns from reigniting.

For now there’s ample water to keep the cores cool, mainly because TEPCO has jury-rigged enough plumbing in the damaged plants to continue pumping water that keeps the cores and fuel pools covered and the meltdowns in check. No one really knows the configuration of the cores, which are presumably in a molten heap on the floor of the containment building, with lethal levels of radioactivity. Robots have made some contact with the cores, but their safe removal is years away.

TEPCO must continue to pump water to keep the cores cool for the indefinite future. As it’s pumped through the system, the fresh water becomes too radioactive itself to release into the environment. So the authorities have been storing this water in giant on-site tanks — now more than 1,000.

They say they’ll run out of room for more tanks in another year or so. The tanks currently hold an estimated 1.2 million tons — more than 300 million gallons — of radioactive water that continues to accumulate at an estimated rate of 1,000 tons (265,000 gallons) or more per week.

No Solution in Sight

TEPCO, which owns the Fukushima complex, and the Japanese government understand the problem well enough, but they have yet to find a reasonable solution. The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) overseeing the Fukushima operation calls for replacing the temporary storage tanks with a permanent solution. Although no feasible permanent solution exists, three have been proposed: Evaporate the water, bury the water deep underground, or pump the water into the Pacific. There is no consensus in support of any of these.

The Japanese government and TEPCO have been advocating the Pacific Ocean dumping solution for more than two years. Authorities say the water has been decontaminated, but this has never been true. At best, the water contains high levels of radioactive, carcinogenic tritium. The filtration device used on the water, the Advanced Liquid Processing System (ALPS), is unable to remove tritium.

In 2017, TEPCO was claiming that ALPS had cleaned the water of every radionuclide other than tritium. That was not true. In August 2018, TEPCO admitted that the treated water still contained radioactive contaminants including iodine, cesium, and strontium, some of them above officially designated safe levels.

As the IAEA has documented, the authorities have released controlled amounts of radioactive water from Fukushima into the Pacific for years. Additionally, uncontrolled radioactive groundwater has flowed into the Pacific continuously since the 2011 disaster, although that flow has been substantially reduced. As the Fukushima site runs out of storage space, the campaign to release 300 million gallons of radioactive wastewater into the Pacific has intensified.

In November 2019, the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists published a status report on Fukushima that began:

After more than eight years, Japan is still struggling with [the] aftermath of the 2011 Fukushima nuclear disaster. The Japanese government and nuclear industry have not solved the many technical, economic, and socio-political challenges brought on by the accident. More worrying, they continue to put special interests ahead of the public interest, exacerbating the challenges and squandering public trust.

Among the problems at Fukushima, the Bulletin cited a highly radioactive exhaust stack that is at risk of collapse and needs to be carefully removed. In 2019, in its first attempt to remove the stack, TEPCO constructed a tower that was three meters too short to do the job. Other glitches have plagued this operation, which is ongoing.

The Bulletin also noted that a subcommittee of the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry recommended dumping treated wastewater with a low level of tritium into the Pacific. However, this plan was stalled by the authorities’ failure to reduce radioactivity to safe levels — or to tell the truth about it.

“Releasing Fukushima radioactive water into ocean is an appalling act of industrial vandalism.”

Further complicating the clean-up at Fukushima, according to the Bulletin, is that none of the institutions involved is a disinterested party and none is willing to accept “a truly independent third party to oversee their activities.”

In December 2019, the New York Times approached the Fukushima story from the perspective of a fisherman whose life has been devastated by the disaster. The fishing industry is operating at about one-fifth the capacity of its pre-meltdown level and is one of the strongest opponents of more dumping. According to the Times:

The water from the Fukushima disaster is more radioactive than the authorities have previously publicized, raising doubts about government assurances that it will be made safe … Some scientists said they would need proof before believing that the Fukushima water was treated to safe levels.

Team leader Juan Carlos Lentijo looks at part of a system that removes radioactive elements from water. Fukushima, Japan, February 11, 2015.

The government official in charge of contaminated-water management acknowledged public concern about the issue, “even though there is no scientific evidence that the water is dangerous.” As if to reinforce that opinion, TEPCO officials hosted a media tour of the Fukushima plant on January 29. Radioactivity on the site is varied, but workers mostly wear protective gear and some jobs are so dangerous only robots are used.

On January 31, after six years of consideration, an advisory panel made a preliminary recommendation to the government to release Fukushima wastewater into the Pacific. The panel decided that this was better than the only alternative they considered feasible: evaporating the water. The recommendation has to be approved by panel chair Ichiro Yamamoto, a step required before the government considers it.

“There should be no delays to decommissioning the plant,” Yamamoto said. There is no reliable estimate as to how long decommissioning the plant’s damaged fuel pools and melted-down reactors will take, but it will surely run to decades. TEPCO’s own timeline stretches past 2050.

On February 3, the Japanese Foreign Ministry briefed 28 diplomats from 23 countries about the proposed radioactive-water dumping into the Pacific. The US did not participate in the briefing. The ministry assured the diplomats that “release of tainted water from Fukushima would have no impact on oceans.” According to the ministry, none of the diplomats voiced any objection to the proposal. The government plans to hold hearings on the proposal.

Reacting to the briefing, Common Dreams (a nonprofit US-based progressive news website) reported: “Nuclear policy expert Paul Dorfman said Saturday, ‘Releasing Fukushima radioactive water into ocean is an appalling act of industrial vandalism.’ Greenpeace opposes the plan as well.”

While South Korea may not have spoken up at the Fukushima briefing, it maintains a ban on Fukushima fish, and closely monitors other produce from Fukushima and seven neighboring prefectures (administrative areas) north and south of it.

Happy Talk

Current media coverage of Fukushima, where it exists, is mostly happy talk about the Olympics and how safe the country has become in the wake of the Fukushima disaster. Radiation that will persist for thousands of years and quiescent nuclear reactors whose meltdowns could reignite any time something else goes wrong are largely ignored.

“Wildlife is thriving in radioactive Fukushima,” according to the Wildlife Society of Bethesda, MD, on February 6, 2020. The Society’s reporting is based on a 2020 study published by the Ecological Society of America in Washington, DC. The limited study used remote sensors to gather data from areas radiologically unsafe for humans (in the so-called human-evacuation zone).

The study found that the radioactive region was repopulated with native mammals and birds, but could reach no conclusion regarding the impact of radiation on individuals or any of their molecular structure. According to the abstract:

Using a network of remote cameras placed along a gradient of radiological contamination and human presence, we collected data on population‐level impacts to wildlife (that is, abundance and occupancy patterns) following the 2011 Fukushima Daiichi nuclear accident. We found no evidence of population‐level impacts in mid‐to large‐sized mammals or gallinaceous birds, and show several species were most abundant in human‐evacuated areas, despite the presence of radiological contamination. These data provide unique evidence of the natural rewilding of the Fukushima landscape following human abandonment, and suggest that if any effects of radiological exposure in mid‐to-large‐sized mammals in the Fukushima Exclusion Zone exist, they occur at individual or molecular scales….

In other words, the researchers have no idea whether or not these populations are “thriving,” only that they appear to have reestablished themselves in pre-meltdown numbers in areas still deemed unsafe for humans.

Is ocean discharge the best solution to Fukushima No. 1’s water crisis?

A government panel has said that releasing radioactive water accumulating at the Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant into the ocean is the most reliable option

Feb 25, 2020

The issue of what to do with the treated radioactive water being stored at the Fukushima No. 1 nuclear plant is nearing its boiling point. Despite plans to install more tanks by the end of the year, the plant’s operator is projected to run out of space around summer 2022.

The estimate by the plant’s manager, Tokyo Electric Power Company Holdings Inc., underscores the fast approaching deadline for the tanks, which now number 1,000.

For three years, an industry ministry panel has been examining five disposal methods for the treated water. In December the number of options was reduced to three: diluting it and dumping it into the sea; letting it evaporate; or a combination of both.

In a report to the government on Feb. 10, the panel recommended releasing the water into the ocean as a more “reliable” method than evaporation, given the practice is common at nuclear power plants here and around the world, and said radiation monitoring would be easier.

One of the major concerns, however, is whether it is safe to discharge the water, which is contaminated mainly with tritium that cannot be removed by ALPS, the advanced liquid processing system installed after the triple-core meltdown in March 2011.

Proponents insist dumping will be safe, arguing that tritium emits beta radiation so weak that the health risks posed will be minimal. The industry ministry estimates that even if all the stored water were to be released into the environment over a one-year period, the resulting radiation exposure would be less than a thousandth of that received from natural background radiation.

Both methods have track records.

Since both volume and radiation levels can be regulated, ocean discharge of tritiated water is a method routinely practiced at nuclear power plants around the world.

Despite scientists’ emphasis on safety, however, opponents argue that either method will again hurt Fukushima’s image, damaging the agriculture, fishing and tourism industries that were just starting to recover from the disaster. The panel noted that risk in its report.

Among Fukushima’s hardest-hit sectors since the disaster is the fisheries industry, which is vehemently opposed to ocean release. They fear the water dumps will ruin a nearly decadelong effort to restore the once-thriving industry, which was forced to halt or restrict operations in waters near the plant.

For the past nine years, fishermen have been conducting operations on a trial basis and measuring catches for radiation before shipping. Amid signs of a recovery, they are now talking about full resumption of fishing.

Because of deep-seated negative perceptions, however, some people still avoid buying fish from Fukushima.

The government is facing a difficult decision balancing the interests of the industries with the shortage of storage space.

South Korean activists and professors sign petition against Japan’s push to dump radioactive water into the ocean

There needs to be a public open debate regarding what to do with the water BEFORE another high magnitude earthquake makes ithe decision for us. There are no easy answers but such a debate will at least serve to highlight the perils of all things nuclear. Pretending everything will be OK is not a credible strategy.

February18, 2020

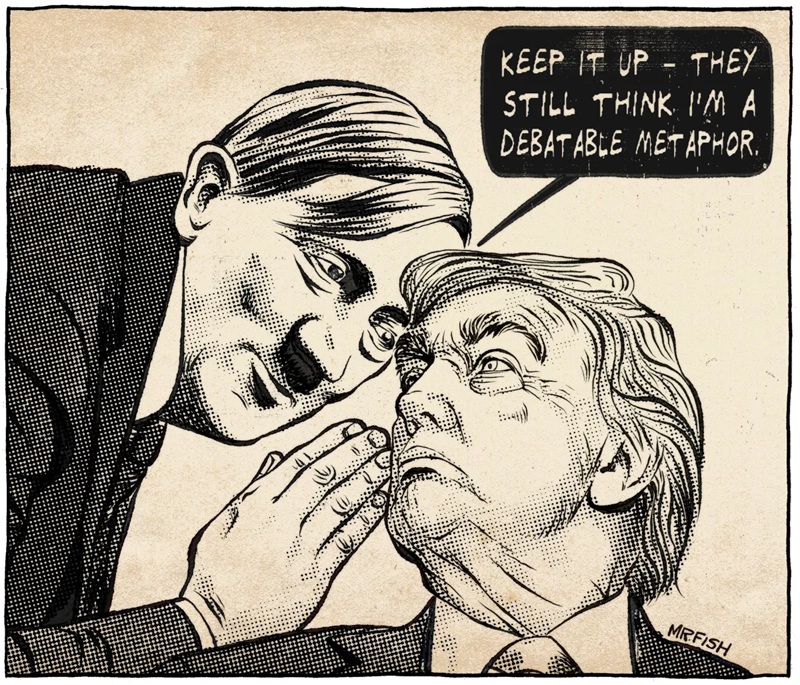

Activists, professors, and civic groups have united to lambast Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe and his push to dump radioactively contaminated water from the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant into the ocean. Referring to such an action as “nuclear terrorism against humanity and a criminal act,” 100 professors, civic group members, and environmental activists have signed a petition calling for Abe to immediately abandon his plans for the dump. The photo shows an artist painting palm prints on a drawing of Abe in protest. (Kim Wan, staff reporter)

Fukushima staff could use raincoats as virus threatens gear production

A trip to the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant: Full-body suits and three layers of socks

This article is just another slick piece of propaganda, downplaying the dangerosity of the situation, a situation still not resolved that after 9 years of lies and cover-up, still not under control.

Among the many B.S. a very good example of its deceitful spin: ” Tepco officials later showed me containers of crystal clear water that had been through ALPS. They said it would be safe to release the liquid into the environment after mixing it with fresh water to meet regulations.”

Sorry Mister, crystal clear water does not make it safe when you’re talking about radioactive water, because remember radiation is invisible. Invisible indeed are the various types of radionuclides contained in that “crystal clear water” that they intend to dump into our ocean. Because as TEPCO admitted last year, their ALPS failed to remove all the Cesiums, Strontium and others, beside Tritium…

The Olympics are near… So the spinned propaganda is up in all japanese media trying to make us all believe how good everything is at Fukushima Daichi nuclear plant, and in contaminated Fukushima prefecture and Tokyo…

Employees of Tokyo Electric Power Company Holdings Inc. wear protective suits and masks inside a radiation filtering Advanced Liquid Processing Systems (ALPS) at the tsunami-crippled Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant in January.

Employees of Tokyo Electric Power Company Holdings Inc. wear protective suits and masks inside a radiation filtering Advanced Liquid Processing Systems (ALPS) at the tsunami-crippled Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant in January.

Feb 5, 2020

OKUMA, FUKUSHIMA PREF. – Reuters was recently given exclusive access to the Fukushima No. 1 nuclear plant, where three reactors melted down in 2011 after a powerful earthquake and tsunami overwhelmed the seaside facility.

It was my fourth visit to the plant since the disaster to report on a massive clean-up. Work to dismantle the plant has taken nearly a decade so far, but with Tokyo due to host the Olympics this summer — including some events less than 60 km (38 miles) from the power station — there has been renewed focus on safeguarding the venues.

Nearly 10 years into the decadeslong clean-up some progress has been made, with potentially dangerous spent fuel removed from the top of one damaged reactor building and removal underway from another.

But the melted fuel inside the reactors has yet to be extracted and areas around the station remain closed to residents. Some towns have been reopened farther away but not all residents have returned.

This time I was taken to the site’s water treatment building, a cavernous hall where huge machines called Advanced Liquid Processing Systems (ALPS) are used to filter water contaminated by the reactors.

Journalist Aaron Sheldrick visits the Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant.

Journalist Aaron Sheldrick visits the Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant.

On my first visit in 2012 I had to wear full protective gear put on at an operations base located in a sports facility about 20 km south of the nuclear plant called J-Village, where the Olympic torch relay will start in March. Then I was taken to the site by bus.

This time I was driven by van from a railway station in Tomioka — a town that was re-opened in 2017 — about 9 km away, with no precautions. More than 90 percent of the plant is deemed to have so little radioactivity that few precautions are needed. Nevertheless, reporting from there was not easy.

Before entering the plant itself, which is about the size of 400 football fields, I was asked to take off my shoes and socks, given a dosimeter to measure radiation levels, three pairs of blue socks, a pair of cloth gloves, a simple face mask, a cotton cap, a helmet and a white vest with clear panels to carry my equipment and display my pass.

I put on all three pairs of socks and the rest of the gear given to me, later including rubber boots. I was to change in and out of different pairs of these boots many times — I lost count — color coded according to the zone we passed through, each time putting them in plastic bags that would be discarded after use.

After reaching the ALPS building in a small bus, I was decked out in protective equipment, a full-body Du Pont Tyvek suit along with two sets of heavy surgeon-like latex gloves that were taped fast to the outfit.

I also had to put on a full-face mask after taking off my glasses since it would not fit otherwise and told to speak as loudly as possible due to the muffling effect of the gear.

“Will you be able to see?” asked one official from Tokyo Electric Power Company Holdings Inc., the plant’s operator. I nodded with as much conviction as I could muster and we entered the building, which was quite dark, making it even harder to see.

A Tepco employee uses a geiger counter next to storage tanks for radioactive water.

A Tepco employee uses a geiger counter next to storage tanks for radioactive water.

In the ALPS building I was taken up and down metal stairways that passed around piping, machinery, testing stations, changing in and out of the rubber boots as we crossed yellow and black demarcations, warning signs everywhere for areas that could not be entered.

As well as being dark, it was surprisingly quiet, given the machinery. My dosimeter alarm kept going off as the radiation levels rose. Tepco officials later showed me containers of crystal clear water that had been through ALPS. They said it would be safe to release the liquid into the environment after mixing it with fresh water to meet regulations.

About 4,000 workers are tackling the cleanup at Fukushima, including dismantling the reactors. Many wear protective gear for entering areas with higher radiation.

The plant resembles a huge construction site strewn in areas with twisted steel and crumpled concrete, along with cars that can no longer be used, while huge tanks to hold water contaminated by contact with the melted fuel in the reactors increasingly crowd the site.

Some wreckage is still so contaminated it is left in place or moved to a designated area for the radiation to decay while the important work on the reactor buildings is underway.

As we moved back into the so-called green zone we passed through a building where I was to take off the protective gear in a precise order in stages, with each piece going into a particular waste basket for each item. Gloves were first, then the facemask, after which the suit and socks were taken off at different locations until I was left with one pair for passing back through the various security cordons.

I was then given my external dosimeter reading, which was 20 microsierverts, about two dental x-rays worth.

High-level radiation at Fukushima Daiichi No.2 reactor

February 4, 2020

Japan’s nuclear regulators say high-level radiation was detected last month in the No.2 reactor building of the crippled Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant.

The Nuclear Regulation Authority last October resumed its probe into what caused the accident at the plant following the March 2011 earthquake and tsunami.

The results of a survey carried out last Thursday on the top floor of the building were disclosed at a meeting of commissioners and experts on Tuesday.

A meltdown took place at the reactor after the 2011 accident.

A robot on the floor directly above the reactor detected 683 millisieverts of radiation per hour.

The plant’s operator, Tokyo Electric Power Company, had also detected high levels of radiation there after the accident.

The site remains inaccessible to humans nine years later.

Commissioners and experts were also shown video of the No.4 reactor, which avoided a meltdown but experienced a hydrogen explosion. The video shows a steel frame believed to have been exposed by the blast.

The regulation authority plans to compile the data into a report this year, not only to determine the cause of the accident but also for work to decommission the reactors.

Japan tries to explain to embassies that releasing Fukushima Radioactive water into ocean is ‘safe’

Japan assures diplomats tainted Fukushima water is safe

Feb. 3 (UPI) — The Japanese government said Monday the planned release of tainted water from Fukushima would have no impact on oceans.

During an information session for foreign embassy officials in Tokyo, the Japanese foreign ministry sent signals of reassurance regarding a plan to release tritium-tainted water from the Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant, the Mainichi Shimbun and Kyodo News reported.

A total of 28 diplomats representing 23 countries were in attendance, according to reports.

The water comes from Fukushima, where 170 tons of water is contaminated every day at the plant that was severely damaged during a catastrophic earthquake in March 2011. Water has been poured to cool the melted fuel, according to Kyodo.

Japan has been purifying the contaminated water using an advanced liquid processing system, or ALPS. The process does not remove tritium and leaves traces of radioactive elements.

Tokyo has defended its plan to release the water, but neighboring countries, including South Korea, are opposed to the measure.

On Monday, officials from Japan’s ministry of economy, trade and industry said they do not think there would be an impact on surrounding countries.

Japanese fishermen also oppose the measure. Releasing the water into the ocean could affect sales of local seafood, they say.

Japan is planning to release the tritium-tainted water at a time when it is taking stricter measures against travelers from China.

Jiji Press reported Monday Japan turned away five foreign nationals originating from Hubei Province following new restrictions at the border.

Foreigners who have stayed in the Chinese province in the past 14 days or who hold passports issued in the province are banned from entry, according to the report.

Japan has confirmed 20 coronavirus cases since the outbreak in China in December. Japanese airports have built new quarantine stations exclusively for travelers from mainland China, Hong Kong and Macau, according to local press reports.

Japan tries to explain to embassies merits of releasing Fukushima water into ocean

February 4, 2020

TOKYO – The Japanese government on Monday tried to impress upon embassy officials from nearly two dozen countries the merits of a plan to release radioactive water from the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant into the ocean.

A briefing session was held at the Foreign Ministry in Tokyo to give an update on how more than 1 million tons of water that have been treated and kept in tanks at the crippled complex will be disposed of as storage space is quickly running out.

Both releasing the water into the Pacific Ocean and evaporating it are “feasible methods” as there are precedents for them in and out of Japan, though the former, in particular, could be carried out “with certainty” because it would be easier to monitor radiation levels, the government explained.

It has said the health risks to humans would be “significantly small,” as discharging the water over a year would amount to between just one-1,600th to one-40,000th of the radiation that humans are naturally exposed to.

But the discharge could cause reputational damage to the fishing and farming industries in the surrounding area, raising the need for countermeasures, the government said in the briefing, which came after the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry on Friday submitted a draft report on the methods to a subcommittee on the issue.

About 170 tons of water is contaminated at the Fukushima plant every day as it is poured onto the wreckage to cool the melted fuel or as it passes through as groundwater.

The contaminated water is being purified using an advanced liquid processing system, or ALPS, though the process does not remove tritium and has been found to leave small amounts of other radioactive materials.

Tanks used to store the treated water are expected to reach capacity by summer 2022.

Local fishermen have voiced opposition to releasing the water into the ocean out of fears that consumers would stop buying seafood caught nearby. Neighboring countries, including South Korea, which currently bans seafood imports from the area, have also expressed unease.

But no embassy officials voiced such concerns at Monday’s briefing, according to the industry ministry.

The briefing was attended by 28 embassy officials from 23 countries and regions — Afghanistan, Belgium, Benin, Brazil, Britain, Cambodia, Canada, Cyprus, East Timor, France, Germany, Italy, Indonesia, Jordan, Lebanon, Moldova, Panama, Russia, South Korea, Switzerland, Taiwan, Turkey and the European Union.

‘An Appalling Act of Industrial Vandalism’: Japanese Officials Do PR for Plan to Dump Fukushima Water Into Ocean

The Japanese government told embassy officials from nearly two dozen countries that releasing the water into the ocean was a “feasible” approach that could be done “with certainty.”

Storage tanks for radioactive water stand at Tokyo Electric Power Co.’s (TEPCO) Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear power plant on Jan. 29, 2020 in Okuma, Fukushima Prefecture, Japan. Tepco hosted a media tour to the nuclear plant wrecked by an earthquake and tsunami in 2011.

Storage tanks for radioactive water stand at Tokyo Electric Power Co.’s (TEPCO) Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear power plant on Jan. 29, 2020 in Okuma, Fukushima Prefecture, Japan. Tepco hosted a media tour to the nuclear plant wrecked by an earthquake and tsunami in 2011.

February 03, 2020

As cleanup of the 2011 Fukushima disaster continues, the Japanese government made its case to embassy officials from 23 countries Monday that dumping contaminated water from the nuclear power plant into the ocean is the best course of action.

According to Kyodo News, officials from the Ministry of Economy, Trade, and Industry claimed releasing the water and evaporating it are both “feasible methods” but said the former could be done “with certainty” because radiation levels could be monitored.

There’s more than one million tons of contaminated water already stored at the plant, with 170 tons more added each day. Utility TEPCO says there will be no more capacity for tanks holding contaminated water by 2022.

As Agence France-Presse reported, “The radioactive water comes from several different sources—including water used for cooling at the plant, and groundwater and rain that seeps into the plant daily—and is put through an extensive filtration process.”

That process still leaves tritium in the water and “has been found to leave small amounts of other radioactive materials,” Kyodo added.

The session for embassy officials followed Friday’s recommendation by a Japanese government panel that releasing the water into the ocean was the most feasible plan. As Reuters reported Friday:

The panel under the industry ministry came to the conclusion after narrowing the choice to either releasing the contaminated water into the Pacific Ocean or letting it evaporate—and opted for the former. Based on past practice it is likely the government will accept the recommendation.

Local fishermen oppose the plan and Reuters noted it is “likely to alarm neighboring countries.”

They’re not alone.

Nuclear policy expert Paul Dorfman said Saturday, “Releasing Fukushima radioactive water into ocean is an appalling act of industrial vandalism.”

Greenpeace opposes the plan as well.

Shaun Burnie, a senior nuclear specialist the group’s German office, has previously called on Japanese authorities to “commit to the only environmentally acceptable option for managing this water crisis, which is long-term storage and processing to remove radioactivity, including tritium.”

Japan’s METI recommends releasing Fukushima Daiichi radioactive water into sea

Japan could decide on fate of radioactive waste water before the Olympics in July

S. Korea, US Discuss Fukushima Wastewater, Marine Issues

January 17, 2020

South Korea and the U.S. held a director-level meeting on maritime and environment issues in Seoul on Thursday.

According to the Foreign Ministry on Friday, the two sides discussed the possibility of Japan releasing contaminated water from the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant disaster site into the ocean.

They also shared views on ways to preserve marine environments.

The two sides discussed how they plan to reduce marine debris and ways to open the Seventh International Marine Debris Conference in South Korea in 2022.

During the meeting, South Korea called on the U.S. to swiftly take steps to remove South Korea from its preliminary list of countries that engage in illegal, unreported, and unregulated(IUU) fishing.

South Korea was designated as a preliminary IUU fishing country by the U.S. after two South Korean fishing boats violated closed fishing grounds and operated near Antarctica in 2017.

http://world.kbs.co.kr/service/news_view.htm?lang=e&Seq_Code=150721

-

Archives

- January 2026 (148)

- December 2025 (358)

- November 2025 (359)

- October 2025 (377)

- September 2025 (258)

- August 2025 (319)

- July 2025 (230)

- June 2025 (348)

- May 2025 (261)

- April 2025 (305)

- March 2025 (319)

- February 2025 (234)

-

Categories

- 1

- 1 NUCLEAR ISSUES

- business and costs

- climate change

- culture and arts

- ENERGY

- environment

- health

- history

- indigenous issues

- Legal

- marketing of nuclear

- media

- opposition to nuclear

- PERSONAL STORIES

- politics

- politics international

- Religion and ethics

- safety

- secrets,lies and civil liberties

- spinbuster

- technology

- Uranium

- wastes

- weapons and war

- Women

- 2 WORLD

- ACTION

- AFRICA

- Atrocities

- AUSTRALIA

- Christina's notes

- Christina's themes

- culture and arts

- Events

- Fuk 2022

- Fuk 2023

- Fukushima 2017

- Fukushima 2018

- fukushima 2019

- Fukushima 2020

- Fukushima 2021

- general

- global warming

- Humour (God we need it)

- Nuclear

- RARE EARTHS

- Reference

- resources – print

- Resources -audiovicual

- Weekly Newsletter

- World

- World Nuclear

- YouTube

-

RSS

Entries RSS

Comments RSS