Grief – Japan marks 12 years since Fukushima nuclear disaster as concerns grow over treated radioactive water release

9 News By Associated Press, Mar 12, 2023

Japan on Saturday marked the 12th anniversary of the massive earthquake, tsunami and nuclear disaster with a minute of silence, as concerns grew ahead of the planned release of the treated radioactive water from the wrecked Fukushima nuclear plant and the government’s return to nuclear energy.

The 9.0 magnitude earthquake and tsunami that ravaged large parts of Japan’s northeastern coast on March 11, 2011, left more than 22,000 people dead, including about 3,700 whose subsequent deaths were linked to the disaster.

A moment of silence was observed nationwide at 2.46pm, the moment the earthquake struck.

Some residents in the tsunami-hit northern prefectures of Iwate and Miyagi walked down to the coast to pray for their loved ones and the 2,519 whose remains were never found.

In Tomioka, one of the Fukushima towns where initial searches had to be abandoned due to radiation, firefighters and police use sticks and a hoe to rake through the coastline looking for the possible remains of the victims or their belongings.

At an elementary school in Sendai, in Miyagi prefecture north of Fukushima, participants released hundreds of colorful balloons in memory of the lives lost.

In Tokyo, dozens of people gathered at an anniversary event in a downtown park, and anti-nuclear activists staged a rally.

The earthquake and tsunami that slammed into the coastal Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant destroyed its power and cooling functions, triggering meltdowns in three of its six reactors.

They spewed massive amounts of radiation that caused tens of thousands of residents to evacuate.

Over 160,000 people had left at one point, and about 30,000 are still unable to return due to long-term radiation effects or health concerns.

Many of the evacuees have already resettled elsewhere, and most affected towns have seen significant population declines over the past decade.

At a ceremony, Fukushima Gov. Masao Uchibori said decontamination and reconstruction had made progress, but “we still face many difficult problems.”

He said many people were still leaving and the prefecture was burdened with the plant cleanup and rumors about the effects of the upcoming release of the treated water.

The plant’s operator, Tokyo Electric Power Company Holdings, and the government are making final preparations to release into the sea more than 1.3 million tons of treated radioactive water, beginning in coming months.

The government says the controlled release of the water after treatment to safe levels over several decades is safe, but many residents as well as neighbours China and South Korea and Pacific island nations are opposed to it.

Fishing communities are particularly concerned about the reputation of local fish and their still recovering business.

In his speech last week, Uchibori urged the government to do utmost to prevent negative rumors about the water release from further damaging Fukushima’s image.

……….. Kishida’s government has reversed a nuclear phase-out policy that was adopted following the 2011 disaster, and instead is pushing a plan to maximise the use of nuclear energy to address energy supply concerns triggered by Russia’s war on Ukraine while meeting decarbonisation requirements.

He said last week that while the energy policy is the central government’s mandate, he wants it to remember that Fukushima continues to suffer from the nuclear disaster. https://www.9news.com.au/world/japan-fukushima-nuclear-disaster-anniversary-concerns-treated-radioactive-water-release/ccd3dc02-52ae-449f-98a8-0475fbdb85ed

12 yrs after Fukushima nuclear disaster, gov’t not facing evacuees’ hardship

March 11, 2023 (Mainichi Japan) Editorial:

https://mainichi.jp/english/articles/20230311/p2a/00m/0op/006000c

Today marks 12 years since the Great East Japan Earthquake of March 11, 2011. Over 22,000 lives were lost due to the cataclysm, including a massive tsunami that struck coastal regions and the disaster at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station.

Today, some 31,000 people are still living as evacuees. Around 90% of them are residents of Fukushima Prefecture. In municipalities mostly within so-called “difficult-to-return zones” where radiation levels are high, many residents have been barred from coming back, and reconstruction has been delayed.

The government is proceeding with decontamination of the areas it has designated as bases for reconstruction within these zones. However, they account for less than 10% of the zones’ total area. It also plans to prepare places outside these reconstruction bases so that people who want to return to those areas can do so, but it is expected that decontamination will be limited to the homes to which people want to return and the surrounding roads. This has left residents who want the whole area decontaminated at a loss.

Local ties lost

The town of Namie in Fukushima Prefecture is a prime example of the difficult circumstances. The current population stands below 2,000 — less than a tenth of what it was before the 2011 disaster. The fact that it has the largest area of difficult-to-return zones, accounting for 80% of the entire town, has put it at a significant disadvantage.

“Even if just one part is decontaminated and a person comes back alone, they can’t live in a mountain village. The government first needs to prepare an environment in which the local community can maintain itself,” stressed Shigeru Sasaki, 68, who has evacuated within Fukushima Prefecture.

Before the disaster, Sasaki lived in the eastern part of the Tsushima district, located in a gorge in Namie. When the Obon season arrived, residents in the settlement would go out together and cut the grass along roads and work together to protect the community.

Since the nuclear disaster, however, the entire Tsushima district has been off-limits as a place to dwell. Sasaki is the deputy leader of a group of 650 plaintiffs in a class action against the government and Fukushima Daiichi operator Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO) Holdings Inc. They are calling for the town to be restored to its original state, bringing radiation levels down to what they were before the disaster, but their claims were rejected by a district court. They are now appealing.

Last year, there was a change in government policy that struck a nerve with those whose lives were turned upside down by the nuclear disaster. The administration of Prime Minister Fumio Kishida effectively extended the operating life of existing nuclear reactors, which had been set at a maximum of 60 years, and also set out to promote replacing them with next-generation nuclear power plants. It is thus lowering the banner of “freedom from reliance on nuclear power” that had been held up from the time of the meltdown.

Sasaki was unable to hide his anger. “We see Tsushima in such a state, yet the government is acting as if the problems in Fukushima are over,” he said.

Meanwhile, some residents have voiced concerns that moves to go back to nuclear power will cause memories of the disaster to fade.

Since 2012, the year after the Fukushima disaster, the Namie Machi Monogatari Tsutae-tai, a town storytellers’ group, has performed picture story shows inside and outside Fukushima Prefecture, conveying the confusion immediately after the disaster and the hardship of life as evacuees. Group founder Yoshihiro Ozawa, 77, lamented, “What was the point of all our activities to date to make sure that people don’t forget the accident?”

Ozawa’s health has deteriorated and so he has given up on returning to Namie, where medical infrastructure remains inadequate. He and his wife still live in the place where they evacuated, and they have little contact with neighbors. He worries about what will happen when one of them ends up alone there.

“My friends and relatives are all scattered. I want people to know that Fukushima still has many issues,” Ozawa said.

Anger at the government for forgetting the lessons of 3.11

While the Japanese government wants to quickly close the book on the nuclear disaster, the locals cannot escape from the disaster’s prolonged effects. There is a wide gap between the perceptions of the two sides.

It is said that it will take several decades to decommission the Fukushima Daiichi reactors. In a survey asking residents why they were hesitant to return, quite a few people cited concerns about nuclear power plant safety, in addition to a lack of hospitals and commercial facilities.

Treated wastewater that continues to accumulate at the Fukushima Daiichi is set to be released into the ocean sometime from this spring onward. However, those in the fishery and others harbor strong concerns about reputational damage. At the end of last year, TEPCO announced compensation standards in the event of such damage, but there are no signs it will be able to gain people’s understanding.

Contaminated soil and other items collected during clean-up efforts across the prefecture remain in interim storage facilities in the local towns of Okuma and Futaba. They are supposed to be moved outside the prefecture for final disposal by 2045, but a destination for the material remains undecided.

Such problems, which are difficult to solve, weigh heavily on the future of the region.

Residents have not only lost their hometowns and a place to live; they have lost the happiness and security of living in close contact with those familiar to them. Twelve years after the outbreak of the nuclear disaster, this sense of profound loss has yet to heal.

The nuclear disaster is not over.

Rather than hurrying to retreat to nuclear power, the government should look squarely at the hardship of each and every resident. It has a responsibility to put effort into supporting them so that wherever they find shelter, they can make connections with people and find a purpose in life.

The voices of the victims

The right to avoid exposure is “a fundamental right to protect human life”

The voices of the victims — Beyond Nuclear International

Firsthand accounts from Fukushima survivors and others afflicted by the nuclear sector

From Nos Voisins Lontains 3.11 (Our Faraway Neighbors 3.11)

Where are the voices of nuclear victims? It is becoming increasingly difficult to hear them. In denial of the harmful consequences of atomic plants, there is an attempt, for example, to downplay and minimize the damage caused by nuclear accidents and more generally the nuclear risk, limiting it merely to the number of deaths.

But there is a far wider web of suffering, especially because nuclear power accidents often do not cause instant, headline-grabbing deaths, but later ones, after a long latency period. This makes them harder to quantify and more easily dismissed.

In the context of the revival of nuclear power in France and Japan, it seems important to return to the field and listen to the voices of the victims. To that end, Nos Voisins Lontains 3.11 has created a new YouTube Channel — Voix des victimes du nucléaire (Voices of the nuclear victims).

In this series, the NGO Nos Voisins Lointains 3.11 (Our Faraway Neighbours 3.11) proposes to broadcast their voices with English subtitles. We are not presenting only the voices of the Fukushima nuclear accident victims, but also more widely the words of the victims of all nuclear uses, military or civil.

We hope that the courage and perseverance of these people will allow the warning voices of so many Cassandras to be heard far and wide, piercing the curse of the powerful nuclear industry and the political powers that support it.

The first video message is from Akiko Morimatsu. You can watch her testimony below. The transcript of her remarks follows.

My name is Akiko MORIMATSU.

The Great East Japan Earthquake of March 11, 2011 was followed by the TEPCO Fukushima Daiichi nuclear accident. What happened to us, the residents of Fukushima? What damage did the people living near the plant suffer? I would like to tell you about it in a concrete way.

On March 11, 2011, I was living in Koriyama, a town in Fukushima Prefecture, located about 60 km from the Fukushima Daiichi plant. There were four of us. Me, my husband and two children. A 5-month-old girl and a 3-year-old boy.

First of all, I would like to tell you that when a nuclear accident occurs, regardless of our age or sex, whether we are for or against nuclear power, we are all confronted with the problem of exposure to radioactivity. Radiation is invisible and colourless. There is no pain or tingling on the skin. And there is the issue of low-dose radiation exposure. At a great distance, you are exposed to low doses of radiation. Besides the fact that radiation cannot be perceived by the senses, people do not die instantly.

In this context, we, living 60km from the plant, lost our home in the Great Earthquake, and then after this natural disaster, we suffered a man-made disaster: the nuclear accident.

Of course, we did not hear the explosions at the nuclear power plant, nor did we see the damaged plant buildings directly. We only learned about the accident through the news on TV. Apart from that, there was no way to know that an accident with explosions took place. There was no way of knowing the exact situation of the Fukushima Daiichi plant, nor how much radiation we would be exposed to.

First of all, I would like to tell you that when a nuclear accident occurs, regardless of our age or sex, whether we are for or against nuclear power, we are all confronted with the problem of exposure to radioactivity. Radiation is invisible and colourless. There is no pain or tingling on the skin. And there is the issue of low-dose radiation exposure. At a great distance, you are exposed to low doses of radiation. Besides the fact that radiation cannot be perceived by the senses, people do not die instantly.

In this context, we, living 60km from the plant, lost our home in the Great Earthquake, and then after this natural disaster, we suffered a man-made disaster: the nuclear accident.

Of course, we did not hear the explosions at the nuclear power plant, nor did we see the damaged plant buildings directly. We only learned about the accident through the news on TV. Apart from that, there was no way to know that an accident with explosions took place. There was no way of knowing the exact situation of the Fukushima Daiichi plant, nor how much radiation we would be exposed to. . We didn’t know how much radiation we had to endure, because neither the state authorities nor the operator TEPCO provided accurate information. We, the people living near the plant, had to make many decisions in this ignorance.

I’m going to tell you about the most difficult thing I have had to do in the last 12 years since the accident. After the explosions at the nuclear power plant, we were well aware of the explosions… But we, who were 60 km away from the plant, were not evacuated by force. Apart from the evacuation order, there was also a confinement order. Gradually, within a radius of 2 km, then 3 km around the nuclear power plant, the population was forcibly evacuated. The circular mandatory evacuation zone gradually expanded. And from 20 to 30 km from the power plant, there was the order to stay indoors. That was the order given by the government. But we, 60 km away, did not receive the confinement order. We were not evacuated either. We were left on our own without any protection.

In this situation, I learned from the TV that the tap water, the drinking water, was contaminated. The first information I got was about the tap water in Kanamachi in Tokyo. They had found radioactive substances in the water. It was on a television program.

The Kanamachi water treatment plant was 200 km from the Fukushima Daiichi plant. We were only 60 km from the plant. Within the 200 km radius, the radioactivity increased, and with the rain radioactive substances contaminated the drinking water. Since the tap water at 200 km from the plant was contaminated, the water at 60 km had to be contaminated without any doubt. So, we learned about the radioactive contamination of our drinking water from the TV news.

Up to that point, it was known that radioactive material had been dispersed, but at 60km, there were no orders to evacuate or to stay indoors. There were repeated statements from the Prime Minister’s Office that there would be no immediate impact on health. The issue of exposure was indeed on our minds. But when I found out that the water in Tokyo was contaminated, and that the water in Fukushima was also contaminated, I realised that I was unknowingly drinking radioactive water. But even after learning this fact, I had to continue drinking the water. And so did my two children, aged 5 months and 3 years. My 5-month-old daughter was clinging to life through breast milk from a mother who was drinking contaminated water.

We also heard on the news that there had been a huge radioactive fallout in and around Fukushima, that shipments of leafy vegetables had been suspended, that farmers were going to lose their livelihoods, and that there had been suicides of desperate farmers. They had lost all hope in the future of their profession. All this we heard on TV.

So, we learned that there really was radioactive contamination. I learned that the farmers had milked the cows, but since shipping was no longer possible, they had to dump the milk in the fields.

As a nursing mother in Fukushima, I thought that we were also mammals like the cows. We humans were also exposed to high doses of radioactivity in the air, and we had to drink tap water, knowing that it was polluted.

I heard about the biological concentration. Milk was even more radioactive than water. That’s why the milk had to be thrown away. Yet I was drinking radioactive water, I was breastfeeding my 5-month-old daughter, and my milk concentrated the radioactivity.

didn’t want to be exposed to radiation myself, and of course I didn’t want my five-month-old child to be exposed to radiation. But we were totally denied the right to choose to refuse exposure. Above all, a baby can’t say she doesn’t want to drink breast milk because it is contaminated. My three-year-old son brought me a glass when he was thirsty, saying “mummy, give me a glass of water”. Knowing that the tap water was contaminated, I was obliged to give him this water.

This is my experience.

The will to avoid exposure, the right to avoid exposure, are fundamental rights to protect life. Their violation is the most serious of all the damages caused by the nuclear accident. I think this issue should be at the heart of the nuclear debate.

I am not the only one who gave poisoned water to our children. Many people living in the area affected by the nuclear disaster had the same experience.

In order to avoid repeating these experiences and to improve the radioprotection policy, I would like you all to think together about the real damage caused by a nuclear accident, starting with whether you can drink radio-contaminated water. I think that this would naturally lead to a certain conclusion.

The most serious damage I suffered from the nuclear accident was that I was subjected to radiation exposure that was not chosen and was avoidable.

This is the most serious damage to which I would strongly like to draw your attention.

Headline photo of Akiko Morimatsu and her son in Geneva at the UN courtesy of Nos Voisins Lontains 3.11.

Fukushima nuclear water plan is a new blow to fishermen

Locals believe livelihoods are at risk as authorities attempt to tackle

contamination 12 years on from the disaster. The authorities are about to

begin pumping contaminated water from the Fukushima nuclear power plant

into the Pacific Ocean.

More than a million tons of water will be released

into the sea over the next thirty years. The waste water will be treated

and diluted to remove most radioactive contaminants, but will still contain

traces of the isotopes, tritium and carbon-14.

The governments of China,

South Korea and Pacific island nations have protested against the decision.

But none are affected more directly than the fishermen of Fukushima. Twelve

years after the catastrophe, there is no clear timeline for the

decommissioning of Fukushima Daiichi, which is decades away from being

safely dismantled.

In the meantime, 130 tons of water is contaminated by it

every day. Some of this is poured directly onto the broken reactors to cool

them. Much is natural ground water which flows through the earth towards

the sea, picking up radiation from the exposed reactors on the way.

To prevent the groundwater reaching the plant in the first place, the

authorities built an underground “ice wall” of frozen earth, but this

has been only partly effective. Filtering is supposed to remove all the

radioactive elements except for tritium, which is routinely released into

the sea in diluted form from nuclear plants around the world

. But carbon-14

and trace elements of more dangerous radioactive substances, including

strontium-90 and iodine-129, have also been detected in the water. The

Japanese government says that tritium will be diluted to less than one-40th

of the concentration permitted under Japanese safety standards and

one-seventh of the World Health Organisation’s permitted level for safe

drinking water.

According to Tepco, the radiation in the tritium in the

water amounts to some 860 trillion becquerels — less than half the 1,620

trillion becquerels released from Britain’s Sellafield plant in 2015. The

theory is that the water will quickly and harmlessly dissipate into the

vastness of the Pacific Ocean.

But environmentalists and some scientists

disagree. The US National Association of Marine Laboratories claims that

the statistics, assumptions and models used in the Tepco projections are

flawed. It points to the danger of concentrated clusters of radiation

accumulating on the ocean floor.

Shaun Burnie, a nuclear expert at

Greenpeace, says that the water should be stored longer in tanks, allowing

time for the tritium to reduce, and that the decision to release into the

ocean is as much as about saving money as science. It also gives an

illusion of concrete progress.

Even if it is safe, it makes little

difference to the fishermen of Soma, for whom even just the perception of a

danger is enough to harm their business. Among them opinion is divided.

Some oppose the release under any circumstances; others, including Konno,

reluctantly accept it as the least worst option given that only complete

decommissioning, decades in the future, will solve the problem.

Times 10th March 2023

National remembrance day , and huge civil case penalty for Tepco executives, but memory of Fukushima now fading in Japan

Japanese offered tearful prayers Saturday on the anniversary of the deadly

tsunami that triggered the Fukushima disaster, but public support for

nuclear power is growing as memories of the 2011 meltdown fade. A minute’s

silence was observed nationwide at 2:46 pm (0546 GMT), the precise moment

when a 9.0-magnitude quake – the fourth strongest in Earth’s recorded

history – devastated northeastern Japan 12 years ago.

In January, Tokyo’s,High Court upheld the acquittal of three former TEPCO executives, again

clearing them of professional negligence over the disaster. But in a

separate civil verdict last year, the trio – plus one other ex-official –

were ordered to pay a whopping 13.3 trillion yen ($97 billion) for failing

to prevent the accident. The enormous compensation sum is believed to be

the largest ever for a Japanese civil case, although lawyers acknowledge it

is well beyond the defendants’ capacity to pay.

The government also plans

to start releasing more than a million tonnes of treated water from the

stricken Fukushima plant into the sea this year. A combination of

groundwater, rainwater that seeps into the area, and water used for

cooling, it has been filtered to remove various radionuclides and kept in

storage tanks on site, but space is running out. The water release plan has

been endorsed by the International Atomic Energy Agency but faces staunch

resistance from local fishing communities and neighbouring countries.

France24 11th March 2023

Twelve years after 3/11, dispute grows over Fukushima’s radioactive soil

BY TOMOKO OTAKE, STAFF WRITER, https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2023/03/10/national/dispute-fukushima-radioactive-soil/

OKUMA, FUKUSHIMA PREF. – On the surface, everything seems to be under control at the expansive site storing radioactive soil collected from across Fukushima Prefecture in the aftermath of the 2011 core meltdowns at the Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant.

Since 2015, the Interim Storage Facility, which straddles the towns of Okuma and Futaba and overlooks the crippled plant, has safely processed massive amounts of radioactive soil — enough to fill 11 Tokyo Domes — in an area nearly five times the size of New York’s Central Park. The soil was collected during decontamination procedures in Fukushima’s cities, towns and villages that were polluted by the disaster.

Here, black plastic bags full of contaminated soil are put on conveyor belts and unpacked. The contents are sifted through to remove plastic, leaves, twigs and other nonsoil waste. Then the soil is taken to dump zones, where it’s buried in 15-meter-deep pits with protective sheeting and a drainage pipe at the bottom so that radioactive cesium won’t leak into the ground. Finally, the soil is covered with noncontaminated soil and topped with a lawn. Areas where the work has been completed look like soccer fields.

The level of radiation here is about 0.2 microsieverts per hour (uSv/h), explained Hiroshi Hattori, an official at the Environment Ministry’s local office, during a recent tour of the areas where the polluted soil is buried. The radiation level there is harmless to humans, though higher than an average of 0.04 uSv/h elsewhere in Japan.

“It’s higher not because of the soil, but because of surrounding forests (which have not been decontaminated).”

The problem is that, as smooth and orderly as its operations are, the site is only a temporary home for the radioactive soil. Nobody knows where this massive pile of dirt will eventually end up. All that is certain is that the central government has pledged to — and is legally obliged to — move all of the soil out of Fukushima Prefecture by 2045.

This unresolved soil issue — along with the lingering dispute over the planned ocean release of tritium-laced wastewater from Fukushima No. 1 — is a sour reminder of the enormous toll the nuclear disaster in Fukushima has inflicted on the country and beyond.

Opposition from residents

The soil is a product of years of state-funded measures to bring radiation levels down in communities affected by the disaster. The government drew up a “decontamination road map” soon after the accident, in the hopes of a speedy return of residents to their hometowns.

The desire to avoid moving the massive amount of soil again — and to make it easier to find a final destination for it — has also led the Environment Ministry to try to reduce its volume first by reusing some of the less contaminated mud for public works projects across the nation. That way, only a quarter of the total amount that contains over 8,000 becquerel per kilogram of cesium will be subject to final disposal, the ministry says.

But it’s a tough sell. In December, the ministry held its first round of meetings with residents in areas of greater Tokyo where pilot projects to utilize the soil under the 8,000 Bq/kg threshold are planned: the Shinjuku Gyoen National Garden in Tokyo, the National Environmental Research and Training Institute in Tokorozawa, Saitama Prefecture, and the National Institute for Environmental studies in Tsukuba, Ibaraki Prefecture.

Nearby residents vehemently opposed the plan. Last month, they formally demanded that the ministry cancel the pilot projects, under which the ministry plans to bury radioactive soil underneath a 50 cm layer of cover soil, for flower beds and parking lots.

Roads, tidal walls and dams

Though little known until recently, the ministry released a policy document in 2016 that outlined the “safe use” of radioactive soil with radiation levels of 8,000 Bq/kg or less. According to the document, the government will divert such soil to embankments in public works projects “whose management entities and responsibilities are clearly defined.”

Roads, tidal walls, seaside protection forest and earthfill dams are some of the projects where use of the soil is envisioned, the document says.

The plan has raised the eyebrows of not just residents but also experts.

“Japan is very seismic and we have (harsh) weather and typhoons,” said Azby Brown, architect and lead researcher for Safecast, a citizen science group that has independently measured and publicized radiation levels in Fukushima and elsewhere.

“The half-life of cesium-137 is 30 years. It’s going to stay radioactive for a long time. What happens when these embankments get old?… It is not a very rational or sound decision, from the sense of certainly the perception of safety.”

Kenichi Oshima, professor of energy policy at Ryukoku University in Kyoto, questions the rationale of treating the soil of 8,000 Bq/kg or less as safe, pointing to a “double standard” between the ministry’s policy and the rigorous control of waste required for other nuclear power plants under the Nuclear Reactor Regulation Law. That law states only waste with radiation levels under 100 Bq/kg is considered safe enough to be reused.

All of the radioactive waste produced by the Fukushima disaster is covered by a separate “special law” that went into force in 2012. This says that Tokyo Electric Power Co. Holdings (Tepco), the operator of Fukushima No. 1, is responsible for the handling of the radioactive waste and soil within its property, while the Environment Ministry is responsible for the disposal of the 3/11-borne radioactive waste outside the plant, though the law itself does not mention the reuse of soil that has been decontaminated.

The ministry has explained that the 8,000 Bq/kg threshold keeps it consistent with the level of “designated waste materials” stipulated in that special legislation. When people are exposed to waste below 8,000 Bq/kg, the additional radiation exposure is limited to less than 1 millisievert per year, not a level that causes health concerns, according to the ministry.

“Granted, soil with 8,000 Bq/kg of radioactive materials is not one that immediately kills people who touch it,” Oshima said. “But it is low-level radioactive waste nonetheless, and so should be managed properly as such, just like low-level radioactive waste from other nuclear power plants is. It’s just inconceivable that it would be utilized as materials for infrastructure that people will be using often.”

Public support elusive

On Feb. 24, Environment Minister Akihiro Nishimura reiterated the ministry’s stance, telling a news conference that utilization of soil outside the prefecture is “important to realize its final disposal outside the prefecture (of Fukushima).”

“We would like to continue explaining our stance in detail so as to nurture public understanding,” he said.

But to nurture this understanding about an issue as serious as radioactive waste, everyone who has a stake should be involved in the decision-making process, Brown says.

“The strong consensus internationally regarding where to put things like radioactive waste requires full agreement and participation by all of the stakeholders, all of the citizens, everyone who’s involved,” Brown said. “What we usually see often in Japan in general, and certainly regarding the Fukushima issues, is that a decision is made at the top. It’s decided, it’s announced and then they try to persuade people to go along with it. This is the case with the water release issue (as well as) the soil issue.”

Around this spring or summer, the government and Tepco hope to begin discharging water that has all the radioactive nuclides except tritium removed. Construction work is already under way at the seaside plant to install an undersea tunnel, through which the water will be released 1 kilometer offshore.

The so-called JESCO law, which went into effect in 2014, gives legal grounds for the creation of the government-funded entity that runs the interim storage site, as well as the obligation for the central government to move the soil out of Fukushima by 2045. The obligation was written into law following a political compromise with the Fukushima Prefectural Government, with officials from the national government saying they “considered the excessive burden” being shouldered by the people of Fukushima.

Both Oshima and Brown, however, say they find the government’s plan to recycle the dirt out of line.

In fact, Oshima says the best solution would be to set aside an area and make it a controlled zone for all the polluted soil for 50 years until the radioactive cesium decays, which is how waste from other nuclear plants is handled, and is what the final disposal site is going to look like.

He cites a 2017 report by the Japan Atomic Energy Agency that estimated the size of the area needed for final disposal, which should be ready by 2045. If the volume of the soil is estimated at 20 million cubic meters, a subsurface ground facility for its final disposal will need to measure about 1.3 km by 1.3 km, the report concluded.

“It may sound like a huge space, but both the national government and Tepco have vacant land plots of that size,” Oshima said. Once the soil’s use as construction materials is greenlighted, however, it would be transported nationwide, and it would be impossible to track and measure its radiation doses, he argued.

“If the soil is properly stored in a controlled area, it would make the public feel so much more at ease.”

What´s happening at Fukushima plant 12 years after meltdown? Massive amounts of fatally radioactive melted nuclear fuel remain inside the reactors.

Japan is preparing to release a massive amount of treated radioactive wastewater

into the sea. Japanese officials say the release is unavoidable and should

start soon.

Dealing with the wastewater is less of a challenge than the

daunting task of decommissioning the plant. That process has barely

progressed, and the removal of melted nuclear fuel hasn´t even started.

TEPCO needs a safety approval from the Nuclear Regulation Authority.

The International Atomic Energy Agency, collaborating with Japan to ensure the

project meets international standards, will send a mission to Japan and

issue a report before the discharge begins………………………..

Massive amounts of fatally radioactive melted nuclear

fuel remain inside the reactors. Robotic probes have provided some

information but the status of the melted debris is largely unknown. Akira

Ono, who heads the cleanup as president of TEPCO´s decommissioning unit,

says the work is “unconceivably difficult.” Earlier this year, a

remote-controlled underwater vehicle successfully collected a tiny sample

from inside Unit 1’s reactor – only a spoonful of about 880 tons of melted

fuel debris in the three reactors.

That’s 10 times the amount of damaged

fuel removed at the Three Mile Island cleanup following its 1979 partial

core melt. Trial removal of melted debris will begin in Unit 2 later this

year after a nearly two-year delay. Spent fuel removal from Unit 1

reactor´s cooling pool is to start in 2027 after a 10-year delay. Once all

the spent fuel is removed the focus will turn in 2031 to taking melted

debris out of the reactors.

Daily Mail 9th March 2023

Little progress seen in removing fuel debris at Fukushima plant

By RYO SASAKI/ Staff Writer, https://www.asahi.com/ajw/articles/14854929, March 6, 2023

Tokyo Electric Power Co. has little to show in removing fuel debris at its Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant in the 12 years since the nuclear disaster started.

The company, in fact, has postponed the work.

An estimated 880 tons of fuel debris remain in the No. 1, 2 and 3 nuclear reactors at the plant.

Remote-control operations must be used to remove the fuel debris because radiation levels in the reactor buildings could kill a person within one hour.

TEPCO had initially planned to start removing fuel debris at the No. 2 reactor, where the level of radiation is comparatively low, by the end of 2022.

However, the company announced in August 2022 that it had abandoned this target, citing delays in developing a robotic arm that could be used to remove the debris.

The company set a new target to start the removal work in the second half of fiscal 2023.

The government and TEPCO aim to complete the decommissioning of the stricken plant between 2041 and 2051.

However, the company’s first goal is to test the retrieval of only several grams of fuel debris. It still hasn’t decided how it will conduct larger-scale removal.

TEPCO has also not explained when it will start removing fuel debris at the No. 1 and No. 3 reactors.

A “submergence method” is under consideration to remove fuel debris from the No. 3 nuclear reactor, but it’s still unclear whether it will be implemented.

With the submergence method, workers would cover the building that houses the No. 3 reactor with a metal structure, fill the inside of the structure with water to submerge the reactor, and then remove fuel debris from the upper part of the building.

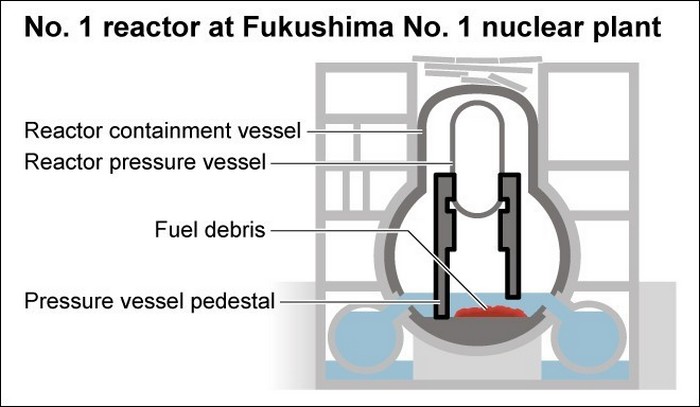

Another worrying factor about the Fukushima nuclear power plant is that the foundation, or “pedestal,” supporting the No. 1 reactor’s pressure vessel has deteriorated so much that the reinforcing bars are now exposed.

Concerns have been expressed about the earthquake resistance of the pedestal.

Fukushima: Japan insists release of 1.3m tonnes of ‘treated’ water is safe

Neighbouring countries and local fishers express concern as 12th anniversary of nuclear disaster looms

Justin McCurry, Guardian 15 Feb 23,

“……………….. As the country prepares to mark the 11 March anniversary, one of the disaster’s most troubling legacies is about to come into full view with the release of more than 1m tonnes of “treated” water from the destroyed Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant.

The tsunami knocked out the plant’s backup electricity supply, leading to meltdowns in three of its reactors, in the world’s worst nuclear accident since Chornobyl 25 years earlier.

Much has changed since the Guardian’s first visit to the plant in 2012, when the cleanup had barely begun and visitors were required to wear protective clothing and full-face masks. Atmospheric radiation levels have dropped, damaged reactor buildings have been reinforced and robots have identified melted fuel in the basements.

But as the Guardian learned on a recent visit, progress on decommissioning – a process that could take four decades – is being held up by the accumulation of huge quantities of water that is used to cool the damaged reactor cores.

Now, 1.3m tonnes of water – enough to fill about 500 Olympic-sized swimming pools – is being stored in 1,000 tanks that cover huge swathes of the complex. And space is running out.

Two steel pillars protruding from the sea a kilometre from the shore mark the spot where, later this year, the plant’s operator, Tokyo Electric Power [Tepco], plans to begin releasing the water into the Pacific Ocean, in the most controversial step in the Fukushima Daiichi cleanup to date.

The decision comes more than two years after Japan’s government approved the release of the water, which is treated using on-site technology to remove most radioactive materials. But the water still contains tritium, a naturally occurring radioactive form of hydrogen that is technically difficult to separate from water.

The discharge, which is due to begin in the spring or summer, will take place in defiance of local fishing communities, who say it will destroy more than a decade of work to rebuild their industry. Neighbouring countries have also voiced opposition.

The government and Tepco claim the environmental and health impacts will be negligible because the treated water will be released gradually after it has been diluted by large amounts of seawater. The International Atomic Energy Agency says nuclear plants around the world use a similar process to dispose of wastewater containing low-level concentrations of tritium and other radionuclides.

Tepco and government officials who guided a small group of journalists around Fukushima Daiichi this month insisted the science supports their plans to pump the “treated” water – they object to media reports describing it as contaminated – into the ocean………………………………………….

Environmental groups have challenged the Japanese government’s claims that the water will not affect marine life or human health, while the US National Association of Marine Laboratories has pointed to a lack of adequate and accurate scientific data to support its reassurances on safety………………….. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2023/feb/15/fukushima-japan-insists-release-of-treated-water-is-safe-nuclear-disaster

Japan Plans to Dump Fukushima Wastewater Into a Pacific With a Toxic Nuclear History

In December, the U.S.-based National Association of Marine Laboratories also announced its opposition to TEPCO’s plans, publishing a position paper that says “there is a lack of adequate and accurate scientific data supporting Japan’s assertion of safety” while “there is an abundance of data demonstrating serious concerns about releasing radioactively contaminated water.”

BY AMY GUNIA , FEBRUARY 6, 2023,

Pacific Island nations have for decades been grappling with the environmental and health consequences of Cold War-era nuclear testing in the region by the likes of the U.S. and France. Now, they worry about another kind of nuclear danger from neighbors much closer to home.

As concerns over energy security and the desire to transition away from fossil fuels pushes several Asian nations to reconsider once-scrapped nuclear power programs, there is increasing anxiety over how the waste from those facilities—depending on the methods of disposal—might impact the lives of Pacific Islanders.

Notably, in the region, Philippines President Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos said in his first address to Congress in mid-2022 that he was open to adding nuclear energy to the country’s energy mix, the Indonesian government said in December it plans to build a nuclear power plant by 2039, and weeks later Japan announced that it plans to ramp up the use of nuclear energy.

Nuclear plants have long been touted as a reliable source of carbon-free energy, though many plants across the world had been shuttered in past decades over worries about the safety of nuclear waste disposal. In this new era of nuclear revival, similar uncertainties abound.

In Japan, one plant that isn’t even operational has become the frontline for the fight between activists seeking safety assurances for waste disposal and operators who are running out of space in on-site tanks to store the wastewater accumulating from keeping damaged reactors cool. Currently, Japan plans to release wastewater from the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant into the Pacific Ocean later this year.

“It’s just horrendous to think what it might mean,” says Henry Puna, the secretary general of the Pacific Islands Forum (PIF), a regional intergovernmental organization that has more than a dozen member countries, including, for example, the Cook Islands, Fiji, Tonga, and Vanuatu. “The people of the Pacific are people of the ocean. The ocean is very much central to our lives, to our culture, to our livelihoods. Anything that prejudices the health of the ocean is a matter of serious concern.”

When a magnitude 9.1 earthquake and tsunami hit off the coast of Japan in 2011, it caused a meltdown at the Fukushima nuclear power plant. Since then, water is being used to cool the damaged reactors and prevent further catastrophe. Now, more than 1.3 million metric tons of radionuclide-contaminated water has been collected on site, and it continues to accumulate, as rain and groundwater seep in. Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO), the operator of the plant, says that the storage tanks take up too much space and hinder decommissioning the plant. Japan initially said that it would begin releasing the water into the ocean in the spring of 2023. Chief Cabinet Secretary Hirokazu Matsuno told the media in January that the release target date is now around spring or summer, which appears to be a postponement, according to the Associated Press, due to construction delays on a pipeline and the apparent need to gain greater public support.

The plan has faced widespread opposition. Japanese fishermen, international environmentalists, and other governments in the region, including China, South Korea, and Taiwan, have all expressed concern. Some of the strongest pushback has come from Pacific Island countries, including from lawmakers, former leaders, regional fisheries management groups, and other organizations. Among those voices is the PIF, which is advocating for more time to deal with questions and concerns. Earlier this year, the PIF appointed a panel of independent global nuclear experts to help inform its members in their consultations with Japan and TEPCO. The experts have stressed that more data are needed to determine the safety of the water for disposal.

“We think that there is not enough scientific evidence to prove that the release is safe, environmentally, healthwise, and also for our economy in the Pacific,” says Puna, who is also the former Prime Minister of the Cook Islands. Until more information is shared and evaluated, he asks that Japan “please defer the discharge of the water.”

……………………………. there appears to be a major disconnect between TEPCO and others, including the PIF panel of experts—who say that they’re concerned with the adequacy, accuracy, and reliability of the data backing up the decision to release the water.

Robert H. Richmond, a research professor and the director of the Kewalo Marine Laboratory at the University of Hawaii at Manoa, who is one of the panel experts, tells TIME that “the critical, foundational data upon which a sound decision could be made was either absent or, when we started getting more data,” he says, “extremely concerning.” He also casts doubt on if the IAEA is in the best position to assess the risks. “They’re an agency that has a mandate to promote the use of nuclear energy,” says Richmond, “and our mandate is to look after the people, the ocean, and the people who depend on the ocean. And our unanimous conclusion … is that this is a bad idea that is not defended properly at this point, and that there are alternatives that Japan should really be looking at.”

“One of the biggest surprises to me was the fact that the data was so sparse,” says Ferenc Dalnoki-Veress, scientist-in-residence and adjunct professor at the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey, who is also on the PIF panel of experts. “There were prolonged gaps in data collection, which suggests that the matter may not have been given the level of attention and importance it deserved.” He adds that only a fraction of the tanks had been sampled, and only a handful of some 60 isotopes were typically measured in the samples—fewer than he would expect for this kind of assessment. (TEPCO says that the analysis done on a sample of tanks so far is just to assess the water’s condition in storage but that, after the purification process, further measurements will be taken on all the treated water before discharge to ensure that only that which meets sufficient standards of safety is released into the ocean).

Some still fear the safety of the treated water, and the far-reaching implications if it’s dumped into the ocean. Puna points out, for example, that the waters of the Western and Central Pacific Ocean produce much of the world’s tuna. If the tuna were to be impacted, it would cause major problems for Pacific nations, for which fisheries are a significant source of income, as well as for consumers globally.

In December, the U.S.-based National Association of Marine Laboratories also announced its opposition to TEPCO’s plans, publishing a position paper that says “there is a lack of adequate and accurate scientific data supporting Japan’s assertion of safety” while “there is an abundance of data demonstrating serious concerns about releasing radioactively contaminated water.”

……………………………………. A scarring past and a new path forward

Other nuclear plants across the globe have released treated wastewater containing tritium. Rafael Mariano Grossi, the IAEA’s director general, said in 2021 that Japan’s plan is “in line with practice globally, even though the large amount of water at the Fukushima plant makes it a unique and complex case.”

But Pacific Island nations have particular reason to be anxious. There is a noxious legacy of nuclear testing in the region, and other countries have historically treated the Pacific as a dumping ground for their waste. The U.S. conducted 67 nuclear tests in the Marshall Islands between 1946 and 1957—and disposed of atomic waste in Runit Dome, where it’s still stored. That testing led not only to forced relocations, but also to increased rates of cancers. Today there is concern that the dome is leaking and that rising sea levels might impact its structural integrity. France also conducted 193 nuclear tests from 1966 to 1996 at Moruroa and Fangataufa atolls in French Polynesia.

…………………….. Rather than let dumping wastewater into the ocean become the norm, at this juncture for nuclear energy, some say it’s an opportunity to explore different ways of doing things. The panel of PIF experts has proposed several alternative solutions, including treating the water and storing it in more secure tanks to allow the tritium time to decay, or using the treated water to make concrete for use in projects that won’t have high contact with humans.

“This is not the first nuclear disaster and by no means is it going to be the last,” says Richmond. “This is an opportunity for Japan,” he says, “to do the right thing and to invest time, effort, and money into determining and coming up with new ways of handling radioactive waste and setting a new trajectory.”

Fukushima nuclear disaster: Japan to release radioactive water into sea this year

By Grace Tsoi BBC News 13 Jan 23,

Japan says it will release more than a million tonnes of water into the sea from the destroyed Fukushima nuclear power plant this year.

After treatment the levels of most radioactive particles meet the national standard, the operator said.

The International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) says the proposal is safe, but neighbouring countries have voiced concern.

The 2011 Fukushima disaster was the worst nuclear accident since Chernobyl.

Decommissioning has already started but could take four decades.

“We expect the timing of the release would be sometime during this spring or summer,” said chief cabinet secretary Hirokazu Matsuno on Friday, adding that the government will wait for a “comprehensive report” from IAEA before the release.

Every day, the plant produces 100 cubic metres of contaminated water, which is a mixture of groundwater, seawater and water used to keep the reactors cool. It is then filtered and stored in tanks.

With more than 1.3 million cubic metres on site, space is running out.

The water is filtered for most radioactive isotopes, but the level of tritium is above the national standard, operator Tepco said. Experts say tritium is very difficult to remove from water and is only harmful to humans in large doses.

However, neighbouring countries and local fishermen oppose the proposal, which was approved by the Japanese government in 2021.

The Pacific Islands Forum has criticised Japan for the lack of transparency.

“Pacific peoples are coastal peoples, and the ocean continues to be an integral part of their subsistence living,” Forum Secretary General Henry Puna told news website Stuff.

“Japan is breaking the commitment that their leaders have arrived at when we held our high level summit in 2021.

“It was agreed that we would have access to all independent scientific and verifiable scientific evidence before this discharge takes place. Unfortunately, Japan has not been co-operating.”……. more https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-64259043

Fukushima water to be released into ocean in next few months, says Japan

Guardian, Justin McCurry in Tokyo, 13 Jan 23,Authorities to begin release of a million tonnes of water from stricken nuclear plant after treatment to remove most radioactive material

The controversial release of more than a million tonnes of water from the wrecked Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant will begin in the northern spring or summer, Japan’s government has said – a move that has sparked anger among local fishing communities and countries in the region.

The decision comes more than two years after the government approved the release of the water, which will be treated to remove most radioactive materials but will still contain tritium, a naturally occurring radioactive form of hydrogen that is technically difficult to separate from water.

Japanese officials insist the “treated” water will not pose a threat to human health or the marine environment, but the plans face opposition from fishermen who say it risks destroying their livelihoods, almost 12 years after a magnitude-9.0 earthquake triggered a huge tsunami that killed more than 18,000 people along Japan’s north-east coast…………………………………….

South Korea and China have voiced concern about the discharge, while the Pacific Islands Forum said recently it had “grave concerns” about the proposed release.

Writing in the Guardian, the forum’s secretary general, Henry Puna, said Japan “should hold off on any such release until we are certain about the implications of this proposal on the environment and on human health, especially recognising that the majority of our Pacific peoples are coastal peoples, and that the ocean continues to be an integral part of their subsistence living”.

The South Korean government, which has yet to lift its ban on Fukushima seafood, has said that releasing the water would pose a “grave threat” to marine life. Fishing unions in the area oppose the release, warning it would cause alarm among consumers and derail more than a decade of efforts to reassure the public that Fukushima seafood is safe to eat…………… more https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2023/jan/13/fukushima-water-to-be-released-into-ocean-in-next-few-months-says-japan

Fukushima, Our ongoing accident.

Dec 19, 2022

What happens to the damaged reactors? The territories evacuated by 160 000 people? What are the new conditions for their return to the contaminated area since the lifting of the governmental aid procedures? Are lessons still being learned by our national operator for its own nuclear plants? We must not forget that a disaster is still unfolding in Japan and that EDF was supposed to upgrade its fleet on the basis of this feedback, which has still not been finalized.

Almost twelve years after the Fukushima disaster, Japan is still in the process of dismantling and ‘decontaminating’ the nuclear power plant, probably for the next thirty to forty years as well. In the very short term, the challenges are posed by the management of contaminated water.

- All the contaminated water will be evacuated into the sea, by dilution over decades

- Each intervention in the accident reactors brings out new elements

- This has an impact on the schedule and the efficiency of the means used

- At the same time, the Japanese government’s objective is to rehabilitate the contaminated areas at any cost

- None of the French reactors is up to date with its safety level according to the post-Fukushima measures promulgated

- Japan will resume its nuclear policy, time having done its work on memories

The great water cycle

Although Japanese politicians claim that they have finally mastered the monster, the colossal task of cleaning up the site is still far from being completed to allow for the ultimate dismantling, with the length of time competing with the endless financing.

After so many years of effort, from decontamination to the management of radioactive materials and maneuvers within the dismantled plant, the actions on site require more and more exceptional means, exclusive procedures, and unprecedented engineering feats (such as robotic probes), while the nuclear fuel inside continues to be cooled permanently by water (not without generating, to repeat, millions of liters of radioactive water).

But the hardest part is yet to come: containing the corium, an estimated 880 tons of molten radioactive waste created during this meltdown of the reactor cores, and managing the thousands of fuel rods. So much so that the complete cleanup and dismantling of the plant could take a generation or more for a total estimated cost of more than 200 billion dollars (according to an assessment published by the German insurer Munich Re, Japan is 150 billion euros), a low range since other estimates raise the bill between 470 and 660 billion dollars, which is not in contradiction with the costs of an accident projected by the IRSN in France.

The removal of this corium will remain the most essential unresolved issue for a long time. Without it, the contamination of this area will continue. In February 2022, the operator Tepco (Tokyo Electric Power Company Holdings Inc.) tried again to approach the molten fuel in the containment of a reactor after a few more or less unsuccessful attempts, the radioactivity of 2 sieverts/hour being the end of everything, including electronic robots. This withdrawal seems quite hypothetical, even the Chernobyl reactor has never been removed and remains contained in a sarcophagus.

(source: Fukushima blog and Japan’s Nuclear Safety Authority NRA)

Until that distant prospect arrives, the 1.37 million tons of water will have filled the maximum storage capacity. This water was used to cool the molten fuel in the reactor and then mixed with rainwater and groundwater. The treatment via an Advanced Liquid Processing System (ALPS) is touted as efficient, but does not remove tritium. Relative performance: Tepco has been repeatedly criticized for concealing and belatedly disclosing problems with filters designed to prevent particles from escaping into the air from the contaminated water treatment system: 24 of the 25 filters attached to the water treatment equipment were found to be damaged in 2021, an already known defect that resulted in no investigation of the cause of the problem and no preventive measures after the filters were replaced.

The management of this type of liquid waste is a problem shared by the Americans. On site, experts say that the tanks would present flooding and radiation hazards and would hamper the plant’s decontamination efforts. So much so that nuclear scientists, including members of the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) and the Japanese Nuclear Regulatory Authority, have recommended controlled release of the water into the sea as the only scientifically and financially realistic option.

In the end, contaminated water would have to be released into the sea through an underwater tunnel about a kilometer offshore, after diluting it to bring the concentration of tritium well below the percentage allowed by regulation (the concentration would be below the maximum limit of tritium recommended by the World Health Organization for drinking water). Scientists say that the effects of long-term, low-dose exposure to tritium on the environment and humans are still unknown, but that tritium would affect humans more when consumed in fish. The health impact will therefore be monitored, which the government already assures us it is anticipating by analyzing 90,000 samples of treated water each year.

Assessment studies on the potential impact that the release of stored contaminated water into the ocean could have therefore seem insufficient. For tritium, in the form of tritiated water or bound to organic matter, in addition to its diverse behavior according to these configurations, is only part of the problem. Some data show great variability in the concentrations of contaminants between the thousand reservoirs, as well as differences in their relative quantities: some reservoirs that are poor in tritium are rich in strontium 90 and vice versa, suggesting a high variability in the concentrations of other radionuclides and a dilution rate that is not so constant. All the ignorance currently resides on the still unknown interactions of the long-lived radioactive isotopes contained in the contaminated water with the marine biology. It is in order to remove all questions that a complete and independent evaluation of the sixty or so radioisotopes is required by many organizations.

As it stands, with the support of the IAEA so that dilution meets expectations, depending on currents, flows …, the release of contaminated materials would take at least forty years. Opponents of such releases persist in proposing an alternative solution of storage in earthquake-resistant tanks in and around the Fukushima facility. For them, “given the 12.3-year half-life of tritium for radioactive decay, in 40 to 60 years, more than 90% of the tritium will have disappeared and the risks will be considerably reduced,” reducing the direct nuisance that could affect the marine environment and even the food chain.

Modelling of marine movements could lead the waste to Korea, then to China, and finally to the Federated States of Micronesia and Palau. As such, each of the impacted countries could bring an action against Japan before the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea to demand an injunction or provisional measures under international law.

Faced with these unresolved health issues, China, South Korea, Taiwan, local fishing communities continue to oppose this management plan, but the work is far from being completed and the problem of storage remains. Just like the ice wall built into the floor of the power plant, the release of contaminated water requires huge new works: the underwater pipe starts at about 16 meters underground and is drilled at a rate of five to six meters per day.

Time is of the essence. The tanks should reach their maximum capacity by the fall of 2023 (the volume of radioactive water is growing at a rate of about 130 to 140 tons per day). But above all, it is necessary to act quickly because the area is likely to suffer another earthquake, a fear noted by all stakeholders. With the major concern of managing the uranium fuel rods stored in the reactors, the risks that radioactivity will be less contained increase with the years.In France, releases to the sea are not as much of a problem: the La Hague waste reprocessing site in France releases more than 11,000 terabecquerels per year, whereas here we are talking about 22 terabecquerels that would be released each year, which is much less than most of the power plants in the world. But we will come back to this atypical French case…

Giant Mikado

The operator Tepco has successfully removed more than 1500 fuel bundles from the reactor No. 4 of the plant since late 2014, but the hundreds still in place in the other three units must undergo the same type of sensitive operation. To do this, again and again, undertake in detail the clearing of rubble, the installation of shields, the dismantling of the roofs of buildings and the installation of platforms and special equipment to remove the rods… And ultimately decide where all the fuel and other solid radioactive debris will have to be stored or disposed of in the long term. A challenge.

The fuel is the biggest obstacle to dismantling. The solution could lie, according to some engineers, in the construction of a huge water-filled concrete tank around one of the damaged reactors and to carry out the dismantling work in an underwater manner. Objectives and benefits? To prevent radiation from proliferating in the environment and exposing workers (water is a radiation insulator, we use this technique in our cooling pools in France) and to maximize the space to operate the heavy dismantling equipment being made. An immersion solution made illusory for the moment: the steel structure enveloping the building before being filled with water is not feasible as long as radiation levels are so high in the reactor building, preventing access by human teams. In short, all this requires a multitude of refinements, the complexity of the reactors adding to the situations made difficult by the disaster.

Experience, which is exceptional in this field, is in any case lacking. What would guarantee the resistance of the concrete of the tanks over such long periods of time, under such hydraulic pressures? The stability of the soils supporting such structures? How can the concrete be made the least vulnerable possible to future earthquakes? How to replace them in the future?

All these difficulties begin to explain largely the delays of 30 to 40 to dismantle. The reactors are indeed severely damaged. And lethal radiation levels equivalent to melted nuclear fuel have been detected near one of the reactor covers, beyond simulations and well above previously assumed levels. Each of the reactors consists of three 150-ton covers, 12 meters in diameter and 60 centimeters thick: the radiation of 1.2 sieverts per hour is prohibitive, especially in this highly technical context. There is also no doubt that other hotspots will be revealed as investigations are carried out at the respective sites. The Nuclear Damage Compensation and Decommissioning Facilitation Corporation (NDF), created in 2014, has the very objective of trying to formulate strategic and technical plans in order to proceed with the dismantling of said reactors. Given the physical and radiological conditions, the technical and logistical high-wire act.

Also, each plan is revised as information is discovered, as investigations are conducted when they are operable. For example, the reinforcing bars of the pedestal, which are normally covered with concrete, are exposed inside Reactor No. 1. The concrete support foundation of a reactor whose core has melted has deteriorated so badly that rebar is now exposed.

The cylindrical base, whose wall is 1.2 meters thick, is 6 meters in diameter. It supports the 440-ton reactor pressure vessel. The reinforcing rods normally covered with concrete are now bare and the upper parts are covered with sediment that could be nuclear fuel debris. The concrete probably melted under the high temperature of the debris. The strength of the pedestal is a major concern, as any defect could prove critical in terms of earthquake resistance.

Nothing is simple. The management of human material appears less complex.

Bringing back to life, whatever it takes

In the mountains of eastern Fukushima Prefecture, one of the main traditional shiitake mushroom industries is now almost always shut down. The reason? Radioactive caesium exceeding the government’s maximum of 50 becquerels per kilogram, largely absorbed by the trees during their growth. More than ten years after the nuclear disaster, tests have revealed caesium levels between 100 and 540 becquerels per kilogram. While cesium C134 has a radioactive half-life of about two years and has almost disappeared by now, the half-life of cesium C137 is about 30 years and thus retains 30% of its radioactivity 50 years after the disaster, and 10% after a century.

As more than two thirds of Fukushima prefecture is covered by forests, nothing seems favorable in the short term to get rid of all or part of the deposited radioactivity, as forests are not part of the areas eligible for ‘decontamination’, unlike residential areas and their immediate surroundings.

On the side of the contaminated residential and agricultural areas, ‘decontamination’ measures have been undertaken. But soil erosion and the transfer of contaminants into waterways, frequent due to typhoons and other intense rain events, are causing the radioactive elements to return, moving them incessantly. Scientists are trying to track radioactive substances to better anticipate geographical fluctuations in doses, but nothing is simple: the phenomena of redistribution of the initial contamination deposits from the mountains to the inhabited low-lying areas are eternal.

The Ministry of the Environment is considering the reuse of decontaminated soils (official threshold of 8,000 becquerels per kilogram), with tests to be conducted. For now, a law requires the final disposal of contaminated soil outside Fukushima Prefecture by 2045, which represents about 14 million cubic meters (excluding areas where radiation levels remain high). This reuse would reduce the total volume before legal disposal.

More generally, Japan has for some years now opted for the strategy of holding radiological contamination as zero and/or harmless. This is illustrated by the representative example of the financial compensation given to farmers, designed so that the difference between pre- and post-accident sales is paid to them as compensation for “image damage”, verbatim.

Finally, in the midst of these piles of scrap metal and debris, it is necessary to make what can be made invisible. Concerning radioactive waste for example, it must be stored in time. On the west coast of the island of Hokkaidō, the villages of Suttsu and Kamoenai have been selected for a burial project. Stainless steel containers would be stored in a vitrified state. But consultation with the residents has not yet been carried out. This is not insignificant, because no less than 19,000 tons of waste are accumulating in the accidental, saturated power plants, and must find a place to rest for hundreds of years to come.

In this sparsely populated and isolated rural area, as in other designated sites, to help with acceptance, 15 million euros are being paid to each of the two municipalities to start the studies from 2020. 53 million are planned for the second phase, and much more in the final stages. This burial solution seems inevitable for Japan, as the waste cannot remain at the level of the surface power plants and is subject at all times to the earthquakes that are bound to occur over such long periods (strong earthquakes have struck off the prefecture in 2021 and 2022). The degrees of dangerousness thus allow the government to impose a default choice, for lack of anything better.

On December 6, 2022, the Director General of the IRSN met with the President of Fukushima University and with a manager of the Institute of Environmental Radioactivity (IER). What was the objective? To show the willingness of both parties to continue ongoing projects on the effects of radioactive contamination on biodiversity and environmental resilience.

But France will not have waited for the health results of a disaster to learn and commit itself to take into account any improvement likely to improve the nuclear safety of its reactors. No ?

Experience feedback

After a few reactor restarts that marked a major change in its nuclear energy policy (ten nuclear reactors from six plants out of a total of fifty-four were restarted by June 2022), the Japanese government is nonetheless planning to build new generation nuclear power plants to support its carbon emission reduction targets. (A memorandum of understanding was signed by the Japan Atomic Energy Agency, Mitsubishi Heavy Industries and Mitsubishi FBR Systems with the American start-up TerraPower to share data for the Natrium fast neutron reactor project; the American company NuScale Power presented its modular reactor technology). But above all, the government is considering extending the maximum service life of existing nuclear reactors beyond 60 years. Following the disaster, Japan had introduced stricter safety standards limiting the operation of nuclear reactors to 40 years, but there is now talk of modernizing the reactors with safety features presented as “the strictest in the world”, necessarily, to meet safety expectations. Their program is worthy of a major refurbishment (GK).

But in France, where are we with our supplementary safety assessments?

The steps taken after the Fukushima disaster to reassess the safety of French nuclear facilities were designed to integrate this feedback in ten years. More than ten years after the start of this process of carrying out complementary safety assessments (CSA), this integration remains limited and the program has been largely delayed in its implementation.

Apparently, ten years to learn all the lessons of this unthinkable accident was not enough. Fear of the probable occurrence of the impossible was not the best motivation to protect the French nuclear fleet from this type of catastrophic scenario, based solely on these new standards. Concerning in detail the reality of the 23 measures identified to be implemented (reinforcement of resistance to earthquake and flooding, automatic shutdown in the event of an earthquake, ultimate water top-up for the reactor and cooling pool, detection of corium in the reactor vessel, etc.), the observation is even distressing: not a single reactor in operation is completely up to standard.

According to NegaWatt’s calculations, at the current rate of progress and assuming that funding and skills are never lacking, it would take until 2040 for the post-Fukushima standards to be finally respected in all French reactors. And even then, some of the measures reported as being in place are not the most efficient and functional (we will come back to the Diesels d’ultime secours, the DUS of such a sensitive model).

Even for the ASN, the reception of the public in the context of post-accident management could appear more important than the effectiveness of the implementation of the measures urgently imposed.

Then, let us complete by confirming that France and Japan have a great and long common history which does not stop in nuclear matters. Among this history, let us recall that Japan lacks facilities to treat the waste from its own nuclear reactors and sends most of it abroad, especially to France. The previous transport of highly radioactive Mox (a mixture of highly toxic plutonium oxide and reprocessed uranium oxide) to Japan dates back to September 2021, not without risk even for the British company specialized in this field, a subsidiary of Orano. The final request for approval for the completion of the Rokkasho reprocessing plant, an important partnership and technology transfer project, is expected in December 2022, although the last shipments to Japan suffered from defective products from Orano’s Melox plant, a frequent occurrence because of a lack of good technical homogenization of the products.

No one is immortal

In the meantime, the ex-managers of the nuclear power plant have been sentenced to pay 95 billion euros for having caused the disaster of the entire eastern region of Japan. They were found guilty, above all, of not having sufficiently taken into account the risk of a tsunami at the Fukushima-Daiichi site, despite studies showing that waves of up to 15 meters could hit the reactor cores. Precisely the scenario that took place.

Worse, Tepco will be able to regret for a long time to have made plan the cliff which, naturally high of 35 meters, formed a natural dam against the ocean and the relatively frequent tsunamis in this seismic zone. This action was validated by the Japanese nuclear safety authorities, no less culpable, on the basis of the work of seismologists and according to economic considerations that once again prevailed (among other things, it was a question of minimizing the costs of cooling the reactors, which would have been operated with seawater pumps).

The world’s fourth largest public utility, familiar with scandals in the sector for half a century, Tepco must take charge of all the work of nuclear dismantling and treatment of contaminated water. With confidence. The final total estimates are constantly being revised upwards, from 11,000 billion to 21,500 billion yen, future budgets that are borrowed from financial institutions, among others, with the commitments to be repaid via the future revenues of the electricity companies. A whole financial package that will rely on which final payer?

Because Tepco’s financial situation and technical difficulties are deteriorating to such an extent that such forty-year timetable projections remain very hypothetical, and the intervention of the State as a last resort is becoming more and more obvious. For example, the Japanese government has stated that the repayment of more than $68 billion in government funding (interest-free loans, currently financed by government bonds) for cleanup and compensation for the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant disaster, owed by Tepco, has been delayed. Tepco’s mandatory repayments have been reduced to $270 million per year from the previous $470 million per year. It is as much to say that the envisaged repayment periods are as spread out as the Japanese debt is abysmal.

Despite this chaotic long-term management, the Japanese government has stated that it is considering the construction of the next generation of nuclear power plants, given the international energy supply environment and Japan’s dependence on imported natural resources. Once the shock is over, business and realpolitik resume.

On a human scale, only radioactivity is immortal.

Bring voices from the coast into the Fukushima treated water debate