Alliance of Pacific organisations condemns Japan’s decision to discharge nuclear wastewater into the Pacific Ocean

NZ and Pacific urged to ‘step up’ against Japan’s nuclear plan, Stuff NZ, Christine Rovoil, Dec 17 2022,

Japan’s decision to discharge nuclear wastewater into the Pacific Ocean for the next 30 years has been condemned by a Pacific alliance.

And the group of community members, academics, legal experts, NGOs and activists is calling on New Zealand and the Pacific to act to stop Japan.

Three reactors at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant had meltdowns after the earthquake and tsunami on March 11, 2011 which left more than 15,000 people dead.

The Japanese government said work to clean up the radioactive contamination would take up to 40 years.

Following the Nuclear Connections Across Oceania Conference at the University of Otago last month, a working group was formed to address the planned discharge.

Dr Karly Burch at the OU’s Centre for Sustainability said many people might be surprised to hear that the Japanese government has instructed Tokyo Electric Power Company (Tepco) to discharge more than 1.3 million tonnes of radioactive wastewater into the ocean from next year.

Burch said they had called on Tepco to halt its discharge plans, and the New Zealand Government to “step up against Japan”.

In June, Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern called for nuclear disarmament during her speech at the Nato Leaders’ Summit in Madrid.

“New Zealand is a Pacific nation and our region bears the scars of decades of nuclear testing. It was because of these lessons that New Zealand has long declared itself proudly nuclear-free,” Ardern said.

Burch said the Government must “stay true to its dedication to a nuclear-free Pacific” by taking a case to the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea against Japan.

“This issue is complex and relates to nuclear safety rather than nuclear weapons or nuclear disarmament,” the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade said in a statement on Friday.

“Japan is talking to Pacific partners in light of their concerns about the release of treated water from Fukushima and Aotearoa New Zealand supports the continuation of this dialogue.

…………….. In Onahama, 60km from the power station, fish stocks have dwindled, said Nozaki Tetsu, of the Fukushima Fisheries Co-operative Associations.

“From 25,000 tonnes per year before 2011, only 5000 tonnes of fish are now caught,” he said. “We are against the release of radioactive materials into our waters. What worries us is the negative reputation this creates.”

………………………. Burch said predictive models showed radioactive particles released would spread to the northern Pacific.

“To ensure they do not cause biological or ecological harm, these uranium-derived radionuclides need to be stored securely for the amount of time it takes for them to decay to a more stable state. For a radionuclide such as Iodine-129, this could be 160 million years.”

………… Burch said the Japanese government was aware in August 2018 that the treated wastewater contained long-lasting radionuclides such as Iodine-129 in quantities exceeding government regulations.

She has called for clarity from Tokyo, the International Atomic Energy Agency, the Pacific Islands Forum Secretariat, Pacific Oceans Commission, and a Pacific panel of independent global experts on nuclear issues on the outcome of numerous meetings they have had about the discharge.

“We want a transparent and accountable consultation process which would include Japanese civil society groups, Pacific leaders and regional organisations.

“These processes must be directed by impacted communities within Japan and throughout the Pacific to facilitate fair and open public deliberations and rigorous scientific debate,” Burch said.

The Pacific Islands Forum secretary-general, Henry Puna, has been approached for comment.

https://www.stuff.co.nz/pou-tiaki/130784783/nz-and-pacific-urged-to-step-up-against-japans-nuclear-plan

Exposed: The Most Polluted Place in the United States

A new book investigates the toxic legacy of Hanford, the Washington state facility that produced plutonium for nuclear weapons.

The Revelator The Ask, December 14, 2022 – by Tara Lohan, The most polluted place in the United States — perhaps the world — is one most people don’t even know. Hanford Nuclear Site sits in the flat lands of eastern Washington. The facility — one of three sites that made up the government’s covert Manhattan Project — produced plutonium for Fat Man, the atomic bomb dropped on Nagasaki during World War II. And it continued producing plutonium for weapons for decades after the war, helping to fuel the Cold War nuclear arms race.

Today Hanford — home to 56 million gallons of nuclear waste, leaking storage tanks, and contaminated soil — is an environmental disaster and a catastrophe-in-waiting.

It’s the costliest environmental remediation project the world has ever seen and, arguably, the most contaminated place on the entire planet,” writes journalist Joshua Frank in the new book, Atomic Days: The Untold Story of the Most Toxic Place in America.

It’s also shrouded in secrecy.

Frank has worked to change that, beginning with a series of blockbuster investigations published in Seattle Weekly a decade ago. Atomic Days offers an even fuller picture of the ecological threats posed by Hanford and its failed remediation.

The Revelator spoke with him about the environmental consequences, the botched cleanup operation, and what comes next.

Why is the most polluted place in the country so little known?

We have to understand what it was born out of, which was the Manhattan Project. There were three locations picked — Los Alamos [N.M.], Oak Ridge [Tenn.] and Hanford — to build the nuclear program.

Hanford was picked to produce plutonium and it ran for four decades, from World War II through the Cold War in the late 80s. For decades people that lived in and around Hanford didn’t know what was really going on there. It was run as a covert military operation. Even now, it’s still very much run like a covert operation because of the dangers that exist with the potential for an attack on one of the nuclear waste tanks……………….

What are the known environmental dangers?

There are 177 underground tanks that hold 56 million gallons of nuclear waste. We know that 67 of those tanks have leaked in the past into the groundwater that feeds the Columbia River.

We know that during its operation in the 50s and 60s the government was monitoring the water in the Columbia River, and even at the mouth of the Columbia they were finding radioactive fish. So we know that there have been leaks that made it to the river.

Right now, we know that there are two tanks currently leaking. The Washington Department of Ecology and the U.S. Department of Energy know about these leaks, but they can’t do anything about them because there’s no other place to safely put the waste…………………………

What has the cleanup process been like?

The big thing right now is trying to get all this waste vitrified, which is turning it into glass so it can be stored safely and permanently. The government thought that could be done in four years, but that was 30 years ago now……………………………………….

Bechtel is a privately owned corporation and we’re spending billions of dollars paying this company to not get the job done. It’s a big mess……………………………………………….. more https://therevelator.org/hanford-nuclear-book/

Dismantling Sellafield: the epic task of shutting down a nuclear site

Nothing is produced at Sellafield anymore. But making safe what is left behind is an almost unimaginably expensive and complex task that requires us to think not on a human timescale, but a planetary one

Guardian, by Samanth Subramanian 15 Dec 22,

“……………………………………………………………………….. Laid out over six square kilometres, Sellafield is like a small town, with nearly a thousand buildings, its own roads and even a rail siding – all owned by the government, and requiring security clearance to visit………. having driven through a high-security gate, you’re surrounded by towering chimneys, pipework, chugging cooling plants, everything dressed in steampunk. The sun bounces off metal everywhere. In some spots, the air shakes with the noise of machinery. It feels like the most manmade place in the world.

Since it began operating in 1950, Sellafield has had different duties. First it manufactured plutonium for nuclear weapons. Then it generated electricity for the National Grid, until 2003. It also carried out years of fuel reprocessing: extracting uranium and plutonium from nuclear fuel rods after they’d ended their life cycles. The very day before I visited Sellafield, in mid-July, the reprocessing came to an end as well. It was a historic occasion. From an operational nuclear facility, Sellafield turned into a full-time storage depot – but an uncanny, precarious one, filled with toxic nuclear waste that has to be kept contained at any cost.

Nothing is produced at Sellafield any more. Which was just as well, because I’d gone to Sellafield not to observe how it lived but to understand how it is preparing for its end. Sellafield’s waste – spent fuel rods, scraps of metal, radioactive liquids, a miscellany of other debris – is parked in concrete silos, artificial ponds and sealed buildings. Some of these structures are growing, in the industry’s parlance, “intolerable”, atrophied by the sea air, radiation and time itself. If they degrade too much, waste will seep out of them, poisoning the Cumbrian soil and water.

To prevent that disaster, the waste must be hauled out, the silos destroyed and the ponds filled in with soil and paved over. The salvaged waste will then be transferred to more secure buildings that will be erected on site. But even that will be only a provisional arrangement, lasting a few decades. Nuclear waste has no respect for human timespans. The best way to neutralise its threat is to move it into a subterranean vault, of the kind the UK plans to build later this century.

Once interred, the waste will be left alone for tens of thousands of years, while its radioactivity cools. Dealing with all the radioactive waste left on site is a slow-motion race against time, which will last so long that even the grandchildren of those working on site will not see its end. The process will cost at least £121bn.

Compared to the longevity of nuclear waste, Sellafield has only been around for roughly the span of a single lunch break within a human life. Still, it has lasted almost the entirety of the atomic age, witnessing both its earliest follies and its continuing confusions. In 1954, Lewis Strauss, the chair of the US Atomic Energy Commission, predicted that nuclear energy would make electricity “too cheap to meter”. That forecast has aged poorly. The main reason power companies and governments aren’t keener on nuclear power is not that activists are holding them back or that uranium is difficult to find, but that producing it safely is just proving too expensive.

… The short-termism of policymaking neglected any plans that had to be made for the abominably lengthy, costly life of radioactive waste. I kept being told, at Sellafield, that science is still trying to rectify the decisions made in undue haste three-quarters of a century ago. Many of the earliest structures here, said Dan Bowman, the head of operations at one of Sellafield’s two waste storage ponds, “weren’t even built with decommissioning in mind”.

As a result, Bowman admitted, Sellafield’s scientists are having to invent, mid-marathon, the process of winding the site down – and they’re finding that they still don’t know enough about it. They don’t know exactly what they’ll find in the silos and ponds. They don’t know how much time they’ll need to mop up all the waste, or how long they’ll have to store it, or what Sellafield will look like afterwards. The decommissioning programme is laden “with assumptions and best guesses”, Bowman told me. It will be finished a century or so from now. Until then, Bowman and others will bend their ingenuity to a seemingly self-contradictory exercise: dismantling Sellafield while keeping it from falling apart along the way.

To take apart an ageing nuclear facility, you have to put a lot of other things together first. New technologies, for instance, and new buildings to replace the intolerable ones, and new reserves of money. (That £121bn price tag may swell further.) All of Sellafield is in a holding pattern, trying to keep waste safe until it can be consigned to the ultimate strongroom: the geological disposal facility (GDF), bored hundreds of metres into the Earth’s rock, a project that could cost another £53bn. Even if a GDF receives its first deposit in the 2040s, the waste has to be delivered and put away with such exacting caution that it can be filled and closed only by the middle of the 22nd century.

Anywhere else, this state of temporariness might induce a mood of lax detachment, like a transit lounge to a frequent flyer. But at Sellafield, with all its caches of radioactivity, the thought of catastrophe is so ever-present that you feel your surroundings with a heightened keenness. At one point, when we were walking through the site, a member of the Sellafield team pointed out three different waste storage facilities within a 500-metre radius. The spot where we stood on the road, he said, “is probably the most hazardous place in Europe”.

Sellafield’s waste comes in different forms and potencies. Spent fuel rods and radioactive pieces of metal rest in skips, which in turn are submerged in open, rectangular ponds, where water cools them and absorbs their radiation. The skips have held radioactive material for so long that they themselves count as waste. The pond beds are layered with nuclear sludge: degraded metal wisps, radioactive dust and debris. Discarded cladding, peeled off fuel rods like banana-skins, fills a cluster of 16-metre-deep concrete silos partially sunk into the earth.

More dangerous still are the 20 tonnes of melted fuel inside a reactor that caught fire in 1957 and has been sealed off and left alone ever since. Somewhere on the premises, Sellafield has also stored the 140 tonnes of plutonium it has purified over the decades. It’s the largest such hoard of plutonium in the world, but it, too, is a kind of waste, simply because nobody wants it for weapons any more, or knows what else to do with it.

…………………………………

………………………………… I only ever saw a dummy of a spent fuel rod; the real thing would have been a metre long, weighed 10-12kg, and, when it emerged from a reactor, run to temperatures of 2,800C, half as hot as the surface of the sun. In a reactor, hundreds of rods of fresh uranium fuel slide into a pile of graphite blocks. Then a stream of neutrons, usually emitted by an even more radioactive metal such as californium, is directed into the pile. Those neutrons generate more neutrons out of uranium atoms, which generate still more neutrons out of other uranium atoms, and so on, the whole process begetting vast quantities of heat that can turn water into steam and drive turbines.

During this process, some of the uranium atoms, randomly but very usefully, absorb darting neutrons, yielding heavier atoms of plutonium: the stuff of nuclear weapons. The UK’s earliest reactors – a type called Magnox – were set up to harvest plutonium for bombs; the electricity was a happy byproduct. The government built 26 such reactors across the country. They’re all being decommissioned now, or awaiting demolition. It turned out that if you weren’t looking to make plutonium nukes to blow up cities, Magnox was a pretty inefficient way to light up homes and power factories.

For most of the latter half of the 20th century, one of Sellafield’s chief tasks was reprocessing. Once uranium and plutonium were extracted from used fuel rods, it was thought, they could be stored safely – and perhaps eventually resold, to make money on the side. Beginning in 1956, spent rods came to Cumbria from plants across the UK, but also by sea from customers in Italy and Japan. Sellafield has taken in nearly 60,000 tonnes of spent fuel, more than half of all such fuel reprocessed anywhere in the world. The rods arrived at Sellafield by train, stored in cuboid “flasks” with corrugated sides, each weighing about 50 tonnes and standing 1.5 metres tall.

………….. at last, the reprocessing plant will be placed on “fire watch”, visited periodically to ensure nothing in the building is going up in flames, but otherwise left alone for decades for its radioactivity to dwindle, particle by particle.

ike malign glitter, radioactivity gets everywhere, turning much of what it touches into nuclear waste. The humblest items – a paper towel or a shoe cover used for just a second in a nuclear environment – can absorb radioactivity, but this stuff is graded as low-level waste; it can be encased in a block of cement and left outdoors. (Cement is an excellent shield against radiation. A popular phrase in the nuclear waste industry goes: “When in doubt, grout.”) Even the paper towel needs a couple of hundred years to shed its radioactivity and become safe, though. A moment of use, centuries of quarantine: radiation tends to twist time all out of proportion.

On the other hand, high-level waste – the byproduct of reprocessing – is so radioactive that its containers will give off heat for thousands of years. …………………………….

Waste can travel incognito, to fatal effect: radioactive atoms carried by the wind or water, entering living bodies, riddling them with cancer, ruining them inside out. During the 1957 reactor fire at Sellafield, a radioactive plume of particles poured from the top of a 400-foot chimney. A few days later, some of these particles were detected as far away as Germany and Norway. Near Sellafield, radioactive iodine found its way into the grass of the meadows where dairy cows grazed, so that samples of milk taken in the weeks after the fire showed 10 times the permissible level. The government had to buy up milk from farmers living in 500 sq km around Sellafield and dump it in the Irish Sea.

From the outset, authorities hedged and fibbed. For three days, no one living in the area was told about the gravity of the accident, or even advised to stay indoors and shut their windows. Workers at Sellafield, reporting their alarming radiation exposure to their managers, were persuaded that they’d “walk [it] off on the way home”, the Daily Mirror reported at the time. A government inquiry was then held, but its report was not released in full until 1988. For nearly 30 years, few people knew that the fire dispersed not just radioactive iodine but also polonium, far more deadly. The estimated toll of cancer deaths has been revised upwards continuously, from 33 to 200 to 240. Sellafield took its present name only in 1981, in part to erase the old name, Windscale, and the associated memories of the fire.

The invisibility of radiation and the opacity of governments make for a bad combination. Sellafield hasn’t suffered an accident of equivalent scale since the 1957 fire, but the niggling fear that some radioactivity is leaking out of the facility in some fashion has never entirely vanished. In 1983, a Sellafield pipeline discharged half a tonne of radioactive solvent into the sea. British Nuclear Fuels Limited, the government firm then running Sellafield, was fined £10,000. Around the same time, a documentary crew found higher incidences than expected of leukaemia among children in some surrounding areas. A government study concluded that radiation from Sellafield wasn’t to blame. Perhaps, the study suggested, the leukaemia had an undetected, infectious cause.

It was no secret that Sellafield kept on site huge stashes of spent fuel rods, waiting to be reprocessed. This was lucrative work. An older reprocessing plant on site earned £9bn over its lifetime, half of it from customers overseas. But the pursuit of commercial reprocessing turned Sellafield and a similar French site into “de facto waste dumps”, the journalist Stephanie Cooke found in her book In Mortal Hands. Sellafield now requires £2bn a year to maintain. What looked like a smart line of business back in the 1950s has now turned out to be anything but. With every passing year, maintaining the world’s costliest rubbish dump becomes more and more commercially calamitous.

The expenditure rises because structures age, growing more rickety, more prone to mishap. In 2005, in an older reprocessing plant at Sellafield, 83,000 litres of radioactive acid – enough to fill a few hundred bathtubs – dripped out of a ruptured pipe. The plant had to be shut down for two years; the cleanup cost at least £300m. …………………………………………………………………………….

Waste disposal is a completely solved problem,” Edward Teller, the father of the hydrogen bomb, declared in 1979. He was right, but only in theory. The nuclear industry certainly knew about the utility of water, steel and concrete as shields against radioactivity, and by the 1970s, the US government had begun considering burying reactor waste in a GDF. But Teller was glossing over the details, namely: the expense of keeping waste safe, the duration over which it has to be maintained, the accidents that could befall it, the fallout of those accidents. Four decades on, not a single GDF has begun to operate anywhere in the world. Teller’s complete solution is still a hypothesis.

Instead, there have been only interim solutions, although to a layperson, even these seem to have been conceived in some scientist’s intricate delirium. High-level waste, like the syrupy liquor formed during reprocessing, has to be cooled first, in giant tanks. Then it is vitrified: mixed with three parts glass beads and a little sugar, until it turns into a hot block of dirty-brown glass. (The sugar reduces the waste’s volatility. “We like to get ours from Tate & Lyle,” Eva Watson-Graham, a Sellafield information officer, said.) Since 1991, stainless steel containers full of vitrified waste, each as tall as a human, have been stacked 10-high in a warehouse. If you stand on the floor above them, Watson-Graham said, you can still sense a murmuring warmth on the soles of your shoes.

Even this elaborate vitrification is insufficient in the long, long, long run. Fire or flood could destroy Sellafield’s infrastructure. Terrorists could try to get at the nuclear material. Governments change, companies fold, money runs out. Nations dissolve. Glass degrades. The ground sinks and rises, so that land becomes sea and sea becomes land. The contingency planning that scientists do today – the kind that wasn’t done when the industry was in its infancy – contends with yawning stretches of time. Hence the GDF: a terrestrial cavity to hold waste until its dangers have dried up and it becomes as benign as the surrounding rock.

A glimpse of such an endeavour is available already, beneath Finland. From Helsinki, if you drive 250km west, then head another half-km down, you will come to a warren of tunnels called Onkalo…………. If Onkalo begins operating on schedule, in 2025, it will be the world’s first GDF for spent fuel and high-level reactor waste – 6,500 tonnes of the stuff, all from Finnish nuclear stations. It will cost €5.5bn and is designed to be safe for a million years. The species that is building it, Homo sapiens, has only been around for a third of that time.

………. In the 2120s, once it has been filled, Onkalo will be sealed and turned over to the state. Other countries also plan to banish their nuclear waste into GDFs…. more https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2022/dec/15/dismantling-sellafield-epic-task-shutting-down-decomissioned-nuclear-site

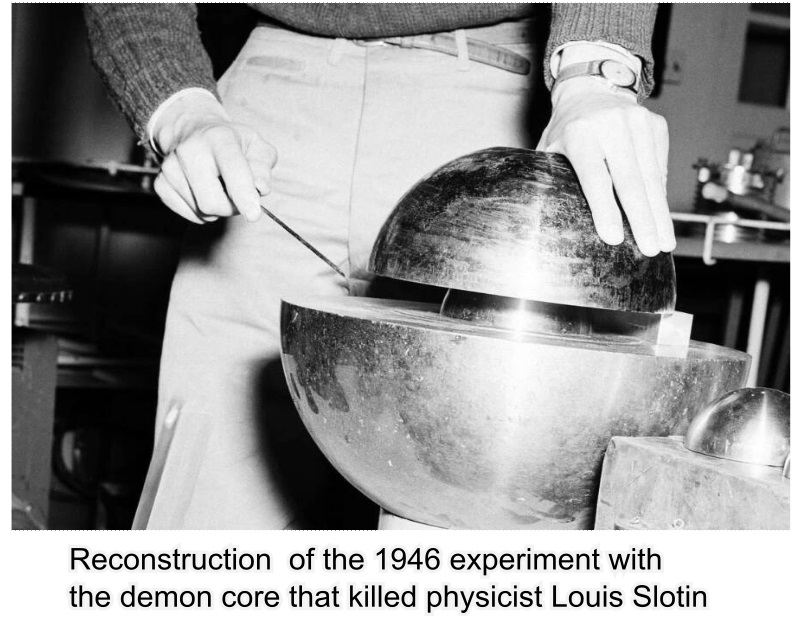

The ‘Demon Core,’ The 14-Pound Plutonium Sphere That Killed Two Scientists

By Kaleena Fraga | Checked By Erik Hawkins https://allthatsinteresting.com/demon-core December 10, 2022

Physicists Harry Daghlian and Louis Slotin both suffered agonizing deaths after making minor slips of the hand while working on the plutonium orb known as the “demon core” at Los Alamos Laboratory in New Mexico.

To survivors of the nuclear attacks in Hiroshima and Nagasaki during World War II, the nuclear explosions seemed like hell on earth. And though a third plutonium core — meant for use if Japan didn’t surrender — was never dropped, it still managed to kill two scientists. The odd circumstances of their deaths led the core to be nicknamed “demon core.”

Retired to the Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico following the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagaski, demon core killed two scientists exactly nine months apart. Both were conducting similar experiments on the core, and both made eerily similar mistakes that proved fatal.

Before the experiments, scientists had called the core “Rufus.” After the deaths of their colleagues, the core was nicknamed “demon core.” So what exactly happened to the two scientists who died while handling it?

The Heart Of A Nuclear Bomb

In the waning days of World War II, the United States dropped two nuclear bombs on Japan. One fell on Hiroshima on Aug. 6, 1945, and one fell on Nagasaki on August 9. In case Japan didn’t surrender, the U.S. was prepared to drop a third bomb, powered by the plutonium core later called “demon core.”

The core was codenamed “Rufus.” It weighed almost 14 pounds and stretched about 3.5 inches in diameter. And when Japan announced its intention to surrender on August 15, scientists at the Los Alamos National Laboratory were allowed to keep the core for experiments.

As Atlas Obscura explains, the scientists wanted to test the limits of nuclear material. They knew that a nuclear bomb’s core went critical during a nuclear explosion, and wanted to better understand the limit between subcritical material and the much more dangerous radioactive critical state.

But such criticality experiments were dangerous — so dangerous that a physicist named Richard Feynman compared them to provoking a dangerous beast. He quipped in 1944 that the experiments were “like tickling the tail of a sleeping dragon.”

And like an angry dragon roused from slumber, demon core would soon kill two scientists at the Los Alamos National Laboratory when they got too close.

How Demon Core Killed Two Scientists

On Aug. 21, 1945, about a week after Japan expressed its intention to surrender, Los Alamos physicist Harry Daghlian conducted a criticality experiment on demon core that would cost him his life. According to Science Alert, he ignored safety protocols and entered the lab alone — accompanied only by a security guard — and got to work.

Daghlian’s experiment involved surrounding the demon core with bricks made of tungsten carbide, which created a sort of boomerang effect for the neutrons shed by the core itself. Daghlian brought the demon core right to the edge of supercriticality but as he tried to remove one of the bricks, he accidentally dropped it on the plutonium sphere. It went supercritical and blasted him with neutron radiation.

Daghlian died 25 days later. Before his death, the physicist suffered from a burnt and blistered hand, nausea, and pain. He eventually fell into a coma and passed away at the age of 24.

Exactly nine months later, on May 21, 1946, demon core struck again. This time, Canadian physicist Louis Slotin was conducting a similar experiment in which he lowered a beryllium dome over the core to push it toward supercriticality. To ensure that the dome never entirely covered the core, Slotin used a screwdriver to maintain a small opening though, Slotin had been warned about his method before.

But just like the tungsten carbide brick that had slipped out of Daghlian’s hand, Slotin’s screwdriver slipped out of his grip. The dome dropped and as the neutrons bounced back and forth, demon core went supercritical. Blue light and heat consumed Slotin and the seven other people in the lab.

“The blue flash was clearly visible in the room although it (the room) was well illuminated from the windows and possibly the overhead lights,” one of Slotin colleagues, Raemer Schreiber, recalled to the New Yorker. “The total duration of the flash could not have been more than a few tenths of a second. Slotin reacted very quickly in flipping the tamper piece off.”

Slotin may have reacted quickly, but he’d seen what happened to Daghlian. “Well,” he said, according to Schreiber, “that does it.”

Though the other people in the lab survived, Slotin had been doused with a fatal dose of radiation. The physicist’s hand turned blue and blistered, his white blood count plummeted, he suffered from nausea and abdominal pain, and internal radiation burns, and gradually become mentally confused. Nine days later, Slotin died at the age of 35.

Eerily, the core had killed both Daghlian and Slotin in similar ways. Both fatal incidences took place on a Tuesday, on the 21st of a month. Daghlian and Slotin even died in the same hospital room. Thus the core, previously codenamed “Rufus,” was nicknamed “demon core.”

What Happened To Demon Core?

Harry Daghlian and Louis Slotin’s deaths would forever change how scientists interacted with radioactive material. “Hands-on” experiments like the physicists had conducted were promptly banned. From that point on, researchers would handle radioactive material from a distance with remote controls.

So what happened to demon core, the unused heart of the third atomic bomb?

Researchers at Los Alamos National Laboratory had planned to send it to Bikini Atoll, in the Marshall Islands, where it would have been publicly detonated. But the core needed time to cool off after Slotin’s experiment, and when the third test at Bikini Atoll was canceled, plans for demon core changed.

After that, in the summer of 1946, the plutonium core was melted down to be used in the U.S. nuclear stockpile. Since the United States hasn’t, to date, dropped any more nuclear weapons, demon core remains unused.

But it retains a harrowing legacy. Not only was demon core meant to power a third nuclear weapon — a weapon destined to rain destruction and death on Japan — but it also killed two scientists who handled it in similar ways.

Nuclear waste permit ‘more stringent’ New Mexico says as feds look to renew for 10 years

Adrian Hedden, Carlsbad Current-Argus, 12 Dec 22

Tougher rules for a nuclear waste repository near Carlsbad could be on the way as New Mexico officials sought “more stringent” regulations as the federal government sought to renew its permit with the state for the facility.

The State sought new requirements to prioritize nuclear waste from within New Mexico for disposal, called for an accounting of all of the waste planned for disposal in the next decade and regular updates on federal efforts to find the location for a new repository as conditions of the permit.

The Waste Isolation Pilot Plant is owned by the U.S. Department of Energy which holds a permit with the New Mexico Environment Department (NMED) that must be updated every 10 years.

The facility sees transuranic (TRU) nuclear waste from DOE facilities around the country disposed of via burial in an underground salt formation about 2,000 feet beneath the surface.

The upcoming renewal, expected by the end of next year, involved negotiations between NMED and the DOE, months of public comments and hearings and multiple expected revisions.

A draft permit was scheduled for public release Dec. 20, and the NMED released on Dec. 8 several conditions it proposed to add to the permit.

The release of the draft will be followed by a 60-day period when NMED will accept comments from the public, and the agency intended to hold a public hearing next summer.

NMED Cabinet Secretary James Kenney said the State wanted a permit with stronger regulations moving forward, to better protect people and the environment from the impacts of nuclear waste disposal.

“It will be more stringent, full stop,” Kenney said. “The conditions were adding to it are designed to add more accountability to the whole complex that are sending waste to WIPP.”………………………………..

State of New Mexico says priority should go to New Mexico nuclear waste

Key among the revisions was prioritizing nuclear waste held at Los Alamos National Laboratory in northern New Mexico, where the DOE develops nuclear weapons.

More:Nuclear waste from Tennessee filling new disposal area at repository near Carlsbad

The facility was recently planned by the DOE to increase production of plutonium pits, used as the triggers for nuclear bombs, as part of efforts to modernize the U.S.’ weapons arsenal.

Kenney said space should be saved at WIPP for New Mexico waste, as the state hosts the repository and he said should receive the most benefit. He said agreements between the DOE and the State of Idaho to prioritize waste from Idaho National Laboratory and another prioritizing waste from Savannah River Site in South Carolina – a facility also set to ramp up pit production – unfairly “leap-frogged” New Mexico for waste disposal.

More:Gov. Lujan Grisham demands President Biden block nuclear waste site in southeast New Mexico

The waste Kenney hoped to target in this provision, he said, was “legacy waste” held at Los Alamos for decades, posing environmental risks in the area and in need of permanent disposal at WIPP.

“We want to make sure we preserve enough space at WIPP for the entirety of New Mexico’s legacy waste,” Kenney said. “I’m significantly concerned that the notion of cap and cover and leaving things around Los Alamos while continuing to emplace waste at WIPP around the country will squeeze out and leave behind waste that should have been there from legacy issues.”

New Mexico aims to hold feds ‘accountable’ for nuclear waste disposal

Another significant change proposed by NMED in the permit would require a full accounting of waste planned to be disposed of at WIPP for the decade following the permit to justify keeping the facility open after the permit expires.

This would better hold the federal government accountable, Kenney said, for future planning at WIPP.

In past proposal for the upcoming permit renewal, the DOE removed a 2024 closure date, opting to leave WIPP’s lifetime open-ended as worked to its statutorily maximum capacity of 6.2 million cubic feet of nuclear waste specified by the federal Land Withdrawal Act (LWA).

The DOE estimated the site could be open until 2085 based on the potential future availability of nuclear waste.

That ambiguity was unacceptable, Kenney said in proposing the added condition.

“We’re not satisfied. That is a completely unacceptable answer. There’s a presumption that if they’re going to continue to operate the underground in New Mexico, they’re going to have to inventory all of the waste that could come to WIPP,” he said.

“They are going to be accountable to every state where they do business including ours. Full accounting, no switching numbers.”

He said he believed WIPP will stay open past the next 10-year permit term, but that the DOE must do a better job at planning future waste streams.

“We know there’s going to be a need for this kind of facility. I don’t think WIPP will reach the LWA limits in 10 years,” Kenney said. “We can’t blindly go down the path of not knowing what they’re doing in every state regarding clean up.”

Nuclear waste facility will ‘run out of volume one day’ state says

As for finding a location for a new nuclear repository to continue disposal of the nation’s nuclear waste, Kenney said he has not seen “anything substantive” from the DOE, but that he did not believe WIPP could be the only repository in the nation for an unlimited amount of time.

But to do that, or to increase WIPP’s capacity, would take an act of Congress, and Kenney said the State of New Mexico should be kept updated on such activities as it held the only deep geological repository for nuclear waste in the U.S.

“There’s an irony with it being called a pilot plant and extending it out to 2080,” Kenney said. “We believe there is a need for this kind of facility. We have legacy waste and we have pit production that has waste that needs a place to go.

“(WIPP) will run out of volume one day. Someone, somewhere in (Washington), D.C. needs to be thinking about where that repository will be.”

Should Congress choose to increase the capacity at WIPP beyond the LWA limit, NMED’s proposal would automatically revoke WIPP’s permit.

This would protect New Mexico, Kenney said, from the being the sole resting place for U.S. nuclear waste.

“That’s a deal breaker for us,” he said. “We’re reclaiming our authority to not let the federal government pull the rug out from under New Mexicans.”

Ricardo Maestas, WIPP program manager at NMED’s Hazardous Waste Bureau also pointed out that the WIPP facility’s proximity to nearby oil and gas operations in the growing Permian Basin region, was so far unaddressed in the permit, and the state should be kept update on fossil fuel operations as they grow around the site. https://www.currentargus.com/story/news/2022/12/10/new-mexico-proposes-tougher-rules-for-nuclear-waste-site-near-carlsbad/69711594007/

The world’s deepest nuclear clean-up – the Dounreay shaft

A £20m contract has been awarded as part of work to clean-up one of the

most challenging features of the Dounreay nuclear power site.

Called the shaft, it plunges 65.4m (214.5ft) below ground and was used for disposing

of radioactive waste. The practice, which started in 1959, ended in 1977

following an explosion inside the structure.

Cavendish Nuclear has been

awarded the contract to build a container handling facility. Waste from the

shaft, and another part of Dounreay called the silo, will be placed in 500

litre drums for storage. Tackling the shaft has been dubbed the world’s

deepest nuclear clean-up by Dounreay’s operators.

BBC 7th Dec 2022

Missouri Community and Its Children Grappling With Exposure to Nuclear Waste

In the 2022 report, BCDC took 32 soil, dust, and plant samples throughout the school buildings and campus. Using x-ray to analyze the samples BCDC found more than 22 times more lead-210 than the estimated exposure levels for the average US elementary school in the Jana Elementary playground alone. There were also more than 12 times the lead-210 expected exposure in the topsoil of the basketball courts alone.

Radioactive isotopes of polonium-210, radium-266, thorium-230, and other toxicants were also found in the library, kitchen, ventilation system, classroom surfaces, surface soil and even soil as far as six feet below the surface.

https://blog.ucsusa.org/chanese-forte/missouri-community-and-its-children-grappling-with-exposure-to-nuclear-waste/ Chanese Forte, December 8, 2022

The families, students, and school officials in Florissant, Missouri have been living a modern nightmare for the past several weeks, learning that Jana Elementary school and the surrounding region has high levels of radiation, a problem caused decades ago by the production of nuclear weapons

Radiation exposure can damage the DNA in cells leading to a host of health problems including cancer and auto-immune disorders. What’s more troubling is that the Centers for Disease Control reports that children and young adults, especially girls and women, are more sensitive to the effects of radiation.

Jana Elementary school has 400 students and a predominantly (82.9%) Black student body. Unfortunately, the United States has a long history of environmental racism which results in harming Black, Indigenous and Brown communities much more in the process of creating and maintaining nuclear weapons.

When science cannot agree, the community suffers

The suburban school north of St. Louis, Missouri, was thought to be safe for students based on research completed in 2000 by the Army Corps of Engineers (USACE).

Specifically, USACE has been in the Coldwater Creek region for the last 20 years attempting to remediate radioactive waste associated with the creek (which does not include Jana Elementary).

Toward the start of the 2022 semester, as part of an ongoing lawsuit in the region the Boston Chemical Data Corp (BCDC), an environmental consulting group, reported the elementary school as having radioactive waste levels far above the estimated national levels.

These radioactive waste exposures—like lead-210—are associated with decreased cognition, brain defects, thyroid disease, and cancer, and can accumulate in the body over time.

Following the BCDC report, all Jana Elementary students were sent home for the rest of the semester in hopes their homes were less toxic.

By the Thanksgiving holiday break, the USACE returned to test inside and on the playground of the school and found no radiation on the campus, news which many community members and organizers unsurprisingly expressed as suspicious.

The School Board then hired SCI Engineering, a private engineering firm, to sample Jana Elementary who came to a similar conclusion as USACE.

Now returning to classes from Thanksgiving break, many wary students joined classes at new schools in the area per the school board’s decision related to BCDC’s radiation exposure assessment. Many parents also expressed to National Public Radio they felt left out of discussions for decisions being made.

How did radioactive waste end up in Florissant, MO?

The region near Jana Elementary was first contaminated by the US Department of Energy’s decision to make St. Louis one of the processing sites for uranium during the Manhattan Engineering District project. These nuclear weapons were built through World War II and originally stored at the St. Louis Lambert International Airport.

Unfortunately, the waste was later illegally dumped in 1973 at the West Lake Landfill in Bridgeton, MO, which lies about 10 miles Southwest of Jana Elementary. The West Lake Landfill is located near the Mallinckrodt Chemical Works Company which regularly floods, causing these harmful chemicals to be carried away by nearby water ways like Coldwater Creek.

Coldwater Creek runs for 19 miles throughout the area and flows directly into the Missouri River. Jana Elementary, just North of St. Louis, is bordered by the creek on two sides but has to date not been included in any clean-up efforts by the US Army Corps of Engineers (USACE).

US Army Corps of Engineers initially didn’t sample inside or outside of Jana Elementary

Prior to the Boston Chem Data Corp 2022 report, the USACE did not take any samples within 300 feet of the school building in their 2017 assessment. According to BCDC’s report, this doesn’t follow US Agency for Toxic Substances Disease Registry (ATSDR) standards for radioactive sampling.

In fact, it ignores the conclusion ATSDR made that most exposures in the region will be indoors and just outdoors of buildings.

Indoor samples from creek-facing homes in the same neighborhood as Jana Elementary had similar radioactive waste both indoors and outdoors. ATSDR also noted in a 2019 report that radioactive wastes are routinely moved from Coldwater Creek into homes due to flooding. The region floods frequently which is only increasing due to climate change in the region.

New radioactive sampling methods used to understand student exposure

In the 2022 report, BCDC took 32 soil, dust, and plant samples throughout the school buildings and campus. Using x-ray to analyze the samples BCDC found more than 22 times more lead-210 than the estimated exposure levels for the average US elementary school in the Jana Elementary playground alone. There were also more than 12 times the lead-210 expected exposure in the topsoil of the basketball courts alone.

Radioactive isotopes of polonium-210, radium-266, thorium-230, and other toxicants were also found in the library, kitchen, ventilation system, classroom surfaces, surface soil and even soil as far as six feet below the surface.

Marco Kaltofen, an environmental engineer who is leading the BCDC team, collected roughly 1,000 samples from across the region as a part of law suit efforts. There are several businesses and homes also indicated as exposed in the lawsuit as well.

Overall, Kaltofen suggests that BCDC’s unprecedented x-ray method better picks up the microscopic radioactive materials. However, he also asserts both studies are essentially saying the same thing, which is of course confusing for many community members.

Community organizers fight for testing and clean-up

Just Moms STL activist Dawn Chapman has worked tirelessly since 2014 to get the federal government to test for radioactive material in more regions where the creek floods.

The co-founder of Just Moms STL, Karen Nickel, also attended Jana Elementary School and has reported currently living with several autoimmune disorders. She uses her experience and love of the area to battle these exposure injustices.

In a 2017 Nation Public Radio report, Ms. Chapman says,

“They [The US Government] fought us for years. Finally, they [tested] parks that had flooded, and found [radioactive waste]. They started testing some backyards and found it. We pushed for Jana Elementary, because it is the closest school to the creek.” Just Moms STL activist, Dawn Chapman

We reached out to Just Moms STL to understand what the next steps are. Just Moms STL Recommends:

- The sites in St. Louis should be expeditiously cleaned up.

Unfortunately, Jana Elementary School is not the only place to be concerned about near St. Louis.- Since remediation of nuclear weapons waste in the area has already taken decades, many of these students will likely age out of Jana Elementary School before there is full remediation of radioactive waste in the St. Louis area.

While there is guidance on defining “safe” or acceptable radioactive exposure levels as it relates to human health, scientists also calculate “expected” levels from the Earth naturally (like radon in sediment).

Unacceptable levels are frequently defined as radiation exposure above natural levels by communities.

- However, legally the Army Corps is allowed to leave some radioactive residue above naturally occurring levels, and Just Moms STL would like this to no longer be the case.

- Residents near nuclear weapon processing sites like the St. Louis area should be included in federal radiation compensation programs, such as the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act (RECA). UCS also suggests consideration of St. Louis in the Energy Employees Occupational Illness Program Act (EEOICPA), and other forms of compensation as well.

Expanding radiation compensation programs is complicated because the list of communities that want to be included who currently qualify is long. Moreover, Just Moms STL says the RECA program needs to be expanded to include processing sites like St. Louis, which has previously only applied to nuclear testing exposure sites and uranium workers, or EEOICPA, which has only covered nuclear site workers, but not surrounding communities.

There are currently two bills being proposed to the House and Senate to extend and strengthen RECA. Just Moms STL is working to get Missouri elected officials to help sponsor and carry RECA as well. And your representatives may also be interested in supporting adjustments to RECA or the EEOICPA.

Misleading claims about the supposed recycling of nuclear wastes

EPZ, the operator of the Borssele nuclear power plant, has long claimed

that they recycle “95 percent” of their nuclear fuel, and that only “5

percent” remains as nuclear waste.

Following a complaint by Laka, the Board

of Appeals of the Dutch Advertising Authority, ruled yesterday that these

are misleading environmental advertisement claims. In its ruling, the board

blames EPZ all the more because theses misleading claims appear on EPZ’s

website under the header “Environment & Health”, where “unsuspecting

visitors should expect accurate and balanced information about nuclear fuel

and nuclear waste.

Laka 1st Dec 2022

Nuclear Free Local Authorities call for Community Partnerships to include critics of the undersea Geological Disposal Facility plan

The Nuclear Free Local Authorities have sent a second letter to each of the

four Community Partnerships responsible for taking forward proposals for a

nuclear waste dump to seek assurances that opponents of the plan should

have a chance to take up membership.

The Community Partnerships in

Allerdale, Mid-Copeland, South-Copeland, all in West Cumbria, and in

Theddlethorpe, in East Lincolnshire, are each pursuing the possibility of

hosting Britain’s many tons of high-level radioactive waste, produced from

Britain’s civil nuclear and military nuclear programmes, in an undersea

Geological Disposal Facility.

NFLA 1st Dec 2022

Uniting to oppose Japanese plan to dump nuclear waste in Pacific

Lydia Lewis, RNZ Pacific Journalist, lydia.lewis@rnz.co.nz, 28 Nov 22,

Activists and academics are joining forces to fight plans by Japan to start dumping nuclear waste from the damaged Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant into the Pacific Ocean.

It is scheduled to start next year and continue for 30 years.

A statement of solidarity opposing the move was being drafted following the Nuclear Connections Across Oceania conference in Dunedin at the weekend.

At least 800,000 tons of radioactive wastewater was scheduled to be dumped into the Pacific Ocean over 30 years from early next year.

“We understand this is within Japan’s jurisdiction but the ocean is not stagnant and Pacific Islands will be at the forefront of disposal,” Pacific Network on Globalisation Deputy Coordinator Joey Tau said.

Pacific anti-nuclear activists, a Hiroshima bomb survivor and academics voiced their opposition at the event and set up a working group to tackle the issue.

International law expert Duncan Currie told the conference Japan had not considered the impacts or conducted baseline studies, which he said was “completely unacceptable”.

He said modelling suggested the waste would travel to Korea, China, and then the Federated States of Micronesia and Palau.

“Japan has other options like storing the waste on land which is costly, but countries need to take a stand now. It is an open and shut case,” Curry said.

“Very simply, any country, any Pacific country, Korea, China could take a case against Japan in the international tribunal of Law of the Sea demanding an injunction or what are called provisional measures in international law be exercised.”

Toshiko Tanaka, an 84-year-old survivor of the atomic bomb attack on Hiroshima in 1945, urged the world to remember the suffering nuclear weapons cause.

Marshallese ‘still suffering’ from nuclear testing

The newly-elected Vanuatu Climate Minister Ralph Regenvanu said Vanuatu was against the move as the country was a member of the Pacific Islands Forum which had expressed its opposition to the dumping.

Fiji-based Bedi Racule said hearing about Japan’s plans and the potential impacts had been re-traumatising as Marshall Islands residents were still facing the impacts of nuclear testing by the United States………………. more https://www.rnz.co.nz/international/pacific-news/479626/uniting-to-oppose-japanese-plan-to-dump-nuclear-waste-in-pacific

Estonian public concerned about radioactive waste from planned nuclear power plant.

The handling of radioactive nuclear waste is one of the public’s biggest

concerns in discussions about potentially building a nuclear power plant in

Estonia, pollsters have found. In 2024, the government will make a decision

on whether or not to build a nuclear power plant in Estonia.

This will be based on a report currently being put together by the Ministry of

Environment. Surveys show nuclear energy is seen as an alternative to using

shale oil to create energy. But the public’s attitudes can be broadly split

into three groups: supporters, opponents and skeptics.

ERR 24th Nov 2022

Confusion over nuclear wastes from small modular reactors

Managing NuScale, other SMR waste will be ‘roughly comparable’ with conventional reactors, DOE labs find Utility Dive Stephen Singer, 23 Nov 22

Dive Brief:

- Two studies differ over how much nuclear waste would be a factor with small modular reactors, or SMRs, such as those planned by NuScale and TerraPower.

- The Argonne and Idaho national laboratories say managing waste from SMRs would have few challenges compared with traditional light water reactors. Spent fuel is thermally hot and highly radioactive, requiring remote handling and shielding.

- A study led by Stanford University and the University of British Columbia says SMRs will generate more radioactive waste than conventional nuclear power plants…………………………… more https://www.utilitydive.com/news/smr-modular-reactor-nuclear-waste-doe-stanford-0

In Suttsu, Japan, residents don’t want nuclear waste

At a time when Japan announces the restart of seventeen nuclear reactors by 2023, the question

of the management of radioactive waste arises. In Suttsu, a landfill project is under study, to the great despair of the inhabitants. “We don’t want our village to become a village of garbage cans”, protest Kazuyuki

Tsuchiya and his wife, Kyoko.

This couple in their seventies runs an inn in Suttsu, located on the island of Hokkaido, in northern Japan. Composed of 78% forest, this village of 2,800 souls, landlocked between mountains and the seaside, is picturesque.

It is here that a nuclear waste storage project has been taking shape since 2020 . The only ones to have applied to the Radioactive Waste Management Company (Numo), created by the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry.

Ouest France 3rd Nov 2022

Radioactive Waste Flasks to Share Arnside Viaduct with Walkers and Cyclists ?

Movers and Shakers including green minded and not so green minded folk are

pushing ahead with the plan to open the Arnside Viaduct to walkers and

cyclists. Whats wrong with that? Nothing apart from the fact that

radioactive waste travels this route to Sellafield on a regular basis.

Several flasks are sometimes taken across the viaduct at a time with at

least two deisel engines required just in case one breaks down as the load

is so very dangerous to the public ..and a target for goodness knows what.

Along with Nuclear Free Local Authorities and Close Capenhurst, Radiation

Free Lakeland recently put a series of questions to Direct Rail Services

who operate the nuclear waste trains on behalf of UK Government. The

replies have so far been unsatisfactory to say the least given that UK

Government is putting public money into ever increasing nuclear waste

flasks journeying to Sellafield alongside public access for walkers and

cyclists sharing the same route over the Arnside Viaduct.

Radiation Free Lakeland 6th Nov 2022

Failure of the “nuclear renaissance” leaves Britain with super-costly closures of reactors, and electricity shortage

UK facing electricity supply woes after nuclear power stations shut, MPs told

Larger and smaller reactors carry risks, island nation failed to keep pace with nuclear fleet closure

Lindsay Clark, 1 Nov 2022 , Electricity shortages appear inevitable for the UK due to the decommissioning of the nation’s aging estate of nuclear power stations, according to evidence submitted by industry to politicians.

…….. Writing to the Commons Science and Technology Committee, Manchester University’s Dalton Nuclear Policy Group said: “Sadly, it is now much too late to avoid a negative impact on the UK’s electricity supply due to the closure of our nuclear fleet. All eleven of Britain’s Magnox plants have been shut down for many years – the last being the Wylfa plant on Anglesey which ceased operation on New Year’s Eve 2015.

It added: “The fleet of Advanced Gas-cooled Reactors (AGRs) operated by [French energy firm] EDF is also now seeing closures.”

In February, the UK government was warned taxpayers would have to make up a multibillion-pound shortfall to decommission nuclear power stations unless a history of overspending is reversed. EDF Energy runs seven AGR stations in the UK, part of eight second-generation reactors set to be decommissioned which provide 16 percent of the nation’s electricity. The AGR stations are scheduled to stop producing electricity by 2028.

Last year the government injected £5.1 billion ($5.8 billion) into the Nuclear Liabilities Fund – now valued at £14.8 billion ($17 billion) – which it set up in 1996 to meet the costs of decommissioning AGR and Pressurized Water Reactor stations. But EDF’s latest cost estimate to decommission the stations in March last year was £23.5bn ($27 billion). Public spending watchdog the National Audit Office has warned more money will be needed unless the government and EDF avoid overspending.

But as well as overspending, decommissioning also presents a problem for electricity supply.

“It is unlikely that there will be any significant extension to these projected dates, although there may be scope for some slight delays in closure. Once the AGRs are all closed, the UK will only have one reactor from the current nuclear fleet still operational – the pressurised water reactor at Sizewell B,” Dalton Nuclear Policy Group said.

……. “it is due to the failure since 2008 – with the exception of the long-delayed Hinkley Point C – of all proposals for a nuclear renaissance in the UK to move from plans to reality,” the group said.

In May, EDF admitted to another year’s delay and £3 billion ($3.5 billion) extra cost in Hinkely Point C – the UK’s first nuclear power station to be built in 20 years. The revised operating date for the site in Somerset is now June 2027 and total costs are estimated to be in the range of £25 billion to £26 billion ($29 billion).

EDF said it would have no cost impact on British consumers or taxpayers. The power station had been due online by 2017 at a cost of around £20 billion ($22 billion)………………….. The Science and Technology Committee is set to hear oral evidence for its inquiry on Delivering Nuclear Power during hearings this week.

The Register 1st Nov 2022

https://www.theregister.com/2022/11/01/electricity_shortages_uk/

-

Archives

- January 2026 (138)

- December 2025 (358)

- November 2025 (359)

- October 2025 (377)

- September 2025 (258)

- August 2025 (319)

- July 2025 (230)

- June 2025 (348)

- May 2025 (261)

- April 2025 (305)

- March 2025 (319)

- February 2025 (234)

-

Categories

- 1

- 1 NUCLEAR ISSUES

- business and costs

- climate change

- culture and arts

- ENERGY

- environment

- health

- history

- indigenous issues

- Legal

- marketing of nuclear

- media

- opposition to nuclear

- PERSONAL STORIES

- politics

- politics international

- Religion and ethics

- safety

- secrets,lies and civil liberties

- spinbuster

- technology

- Uranium

- wastes

- weapons and war

- Women

- 2 WORLD

- ACTION

- AFRICA

- Atrocities

- AUSTRALIA

- Christina's notes

- Christina's themes

- culture and arts

- Events

- Fuk 2022

- Fuk 2023

- Fukushima 2017

- Fukushima 2018

- fukushima 2019

- Fukushima 2020

- Fukushima 2021

- general

- global warming

- Humour (God we need it)

- Nuclear

- RARE EARTHS

- Reference

- resources – print

- Resources -audiovicual

- Weekly Newsletter

- World

- World Nuclear

- YouTube

-

RSS

Entries RSS

Comments RSS