Hanford begins removing waste from 24th single-shell tank.

Nuclear Newswire, Thu, Feb 12, 2026,

The Department of Energy’s Office of Environmental Management said crews at the Hanford Site near Richland, Wash., have started retrieving radioactive waste from Tank A-106, a 1-million-gallon underground storage tank built in the 1950s.

Tank A-106 will be the 24th single-shell tank that crews have cleaned out at Hanford, which is home to 177 underground waste storage tanks: 149 single-shell tanks and 28 double-shell tanks. Ranging from 55,000 gallons to more than 1 million gallons in capacity, the tanks hold around 56 million gallons of chemical and radioactive waste resulting from plutonium production at the site.

According to the Washington Department of Ecology, at least 68 of Hanford’s tanks are assumed to have leaked in the past, and three are currently leaking.

The transfer: Tank A-106 contains about 80,000 gallons of solid waste, which now are being transferred to one of the newer, double-shell tanks for continued safe storage. A-106 is one of two tanks currently undergoing retrieval operations by the Hanford Field Office and its tank operations contractor, Hanford Tank Waste Operations and Closure (H2C). In March 2025, H2C began retrieving waste from Tank A-102, a 1-million-gallon tank holding about 41,000 gallons of solid waste……………………………

Hanford’s waste tanks are organized into 18 different groups, called tank farms. The A Tank Farm, which contains six tanks, each with a million-gallon capacity, is the third farm to undergo retrieval at the site. Retrieval field operations on the farm’s first tank and Hanford’s 22nd single-shell tank, A-101, were completed last September……………………………… https://www.ans.org/news/2026-02-11/article-7751/hanford-begins-removing-waste-from-24th-singleshell-tank/

The Future of Los Alamos Lab: More Nuclear Weapons or Cleanup?

New Mexico Environment Department Issues Corrective Action Order

February 11, 2026, Jay Coghlan, lScott Kovac, nukewatch.org

Santa Fe, NM – In its own words, “The New Mexico Environment Department [NMED] issued several actions today to hold the U.S. Department of Energy accountable for failing to prioritize the cleanup of Los Alamos National Laboratory’s “legacy waste” for disposal at the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant.”

Amongst these actions is an Administrative Compliance Order designed to hasten cleanup of an old radioactive and toxic waste dump that should be the model for Lab cleanup. Nuclear Watch New Mexico strongly supports NMED’s aggressive efforts to compel comprehensive cleanup given Department of Energy obstruction.

This Compliance Order comes at a historically significant time. On February 5 the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty expired, leaving the world without any arms control for the first time since the middle 1970s. The following day the Trump Administration accused China of conducting a small nuclear weapons test in 2020, possibly opening the door for matching tests by the United States.

NMED’s Compliance Order comes as LANL’s nuclear weapons production programs are radically expanding for the new nuclear arms race. The directors of the nuclear weapons laboratories, including LANL’s Thom Mason, are openly talking about seizing the opportunity provided by the Trump Administration’s deregulation of nuclear safety regulations to accelerate nuclear warhead production.

As background, in September 2023 NMED released a groundbreaking draft Order mandating the excavation and cleanup of an estimated 198,000 cubic meters of radioactive and toxic wastes at Material Disposal Area C, an old unlined dump that last received wastes in 1974. However, in a legalistic maneuver to evade real cleanup, DOE unilaterally declared that Area C:

“…is associated with active Facility operations and will be Deferred from further corrective action under [NMED’s] Consent Order until

it is no longer associated with active Facility operations.”

The rationale of DOE’s semi-autonomous nuclear weapons agency, the National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA), is that Area C is within a few hundred yards of the Lab’s main facility for plutonium “pit” bomb core production. LANL is prioritizing that production above everything else while cutting cleanup and nonproliferation programs and completely eliminating renewable energy research. DOE’s and NNSA’s unilateral deferment of Area C until it “is no longer associated with active Facility operations” in effect means that it will never be cleaned up. No future plutonium pit production is to maintain the safety and reliability of the U.S.’ existing nuclear weapons stockpile. Instead, it is all for new design nuclear weapons for the new arms race that the NNSA intends to produce until at least 2050. Further, new-design nuclear weapons could prompt the United States to resume full-scale testing, which would have disastrous international proliferation consequences.

To break up the legalistic log jam around cleanup of Area C, NMED’s new Administrative Compliance Order orders DOE, NNSA, and their contractors to:

1) Provide within 30 days specific justifications for their unilateral “deferment” of an old radioactive and toxic waste dump from cleanup; and

2) Rescind their withdrawal of a 2021 “Corrective Measures Evaluation” (CME) which proposed possible cleanup methods. DOE had claimed that withdrawing the CME had mooted any legal basis for NMED to mandate comprehensive cleanup at LANL.

The Lab’s budget for nuclear weapons programs that caused the need for cleanup has more than doubled over the last decade, with a one billion dollar increase in this year alone. Nevertheless, DOE et al want cleanup on the cheap. Their plan is to “cap and cover” existing wastes, leaving them permanently buried in unlined pit and trenches as a perpetual threat to groundwater.

Ironically, there is no current need for pit production. In 2006 independent experts concluded that plutonium pits have serviceable lifetimes of at least 100 years (their average age now is ~43). Moreover, at least 20,000 existing pits are already stored at the NNSA’s Pantex Plant near Amarillo, TX.

Pit production is the NNSA’s most complex and expensive program ever. It will likely cost more than $60 billion over the next 25 years, exceeding the cost of the original Manhattan Project that designed and built a plutonium pit from scratch. However, the independent Government Accountability Office has repeatedly concluded that the NNSA has no credible cost estimates and no “Integrated Master Schedule” for planned redundant pit production at LANL and the Savannah River Site in South Carolina

In addition, it’s not clear where an estimated 57,500 cubic meters of radioactive transuranic wastes from future pit production will go. DOE is fundamentally changing the cleanup mission of the only existing permanent repository, the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant (WIPP) in southern New Mexico, to become the dumping ground for new nuclear bomb production. However, WIPP is already oversubscribed for all of the radioactive wastes that DOE wants to send to it. Moreover, NMED has previously ordered DOE to prioritize disposal of LANL’s Cold War wastes at WIPP (which it is not doing) and to begin looking for a new out-of-state waste dump, which will be politically controversial.

In all, NNSA’s expanded plutonium pit production is so plagued with problems that the DOE Deputy Secretary ordered a “special assessment” of the program completed by December 8, 2025. However, it is still not publicly available.

LANL and DOE have a long history of deception concerning contamination and cleanup. In 1992 a Lab pamphlet was inserted into the Sunday edition of The New Mexican newspaper which claimed that plutonium from LANL had never been found in the Rio Grande. This was despite the fact that a 1987 study detected Lab plutonium 17 miles south down the Rio Grande in Cochiti Lake, a popular recreational site.

As late as the late 1990s LANL was claiming that groundwater contamination was impossible, going so far as to request a waiver from even having to monitor for it (fortunately denied by NMED). Today we know of a massive hexavalent chromium plume whose size is still not known that has migrated onto San Ildefonso Pueblo lands (Lab maps showed it stopping at exactly the Pueblo border). Plutonium, high explosives and perchlorates have all been detected in groundwater. A 2005 hydrogeological study concluded that “Future contamination at additional locations is expected over a period of decades to centuries as more of the contaminant inventory reaches the water table.”

In 2018 DOE was falsely claiming that cleanup at the Lab was more than half complete. In Nuclear Watch New Mexico’s view, genuine cleanup of LANL has yet to begin. It will start with a final Order by NMED to DOE mandating excavation and treatment of the radioactive and toxic wastes at Area C. Lab-wide comprehensive cleanup is the only sure way to protect New Mexico’ life-sustaining groundwater and will provide hundreds of long-term, high paying jobs.

Jay Coghlan, Director of Nuclear Watch New Mexico, commented: “What is more important to New Mexicans, clean, uncontaminated groundwater or more nuclear weapons for the accelerating global arms race? We salute NMED’s efforts under the leadership of Secretary James Kenney to hold the Lab accountable and make it genuinely clean up. This enforcement action is a crucial step toward reining in Lab contamination. But it is also a global step in forcing the Los Alamos Lab to focus on cleanup instead of the buildup of nuclear weapons for another arms race that threatens us all.”

WANTED: Volunteers to host nuclear waste, forever

By Sarah Mcfarlane, Timothy Gardner and Susanna Twidale, February 6, 2026, https://www.reuters.com/sustainability/land-use-biodiversity/wanted-volunteers-host-nuclear-waste-forever-2026-02-06/

- U.S. wants campuses to host nuclear facilities and data centers

- Asks states to volunteer, permanent waste disposal a must-have

- No deep geological waste facility yet in operation worldwide

LONDON/WASHINGTON, Feb 6 (Reuters) – The Trump administration’s plan to unleash a wave of small futuristic nuclear reactors to power the AI era is falling back on an age-old strategy to dispose of the highly toxic waste: bury it at the bottom of a very deep hole.

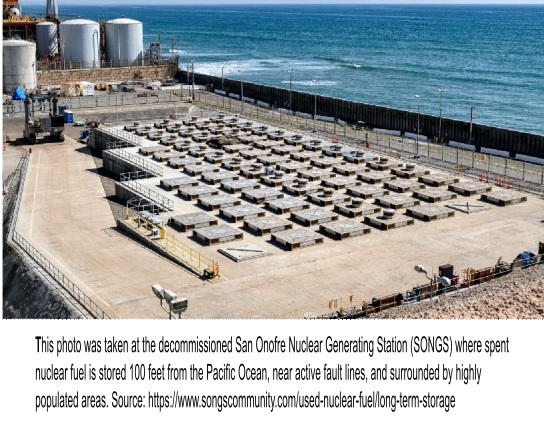

But there’s a problem. There is no very deep hole, and the stockpile of some 100,000 tons of radioactive waste being stored temporarily at nuclear plants and other sites across the United States keeps getting bigger.

To resolve this quandary, the U.S. administration is now dangling a radioactive carrot.

States are being asked to volunteer to host a permanent geological repository for spent fuel as part of a campus of facilities including new nuclear reactors, waste reprocessing, uranium enrichment and data centers, according to a proposal published by the Department of Energy (DOE) last week.

Its request for information (RFI) marks a big shift in policy. The plan to boost nuclear energy is now combined with a requirement to find a permanent home for waste and puts decisions in the hands of local communities – decisions worth tens of billions of dollars in investment and thousands of jobs, according to a spokesperson for the DOE’s Office of Nuclear Energy.

“By combining this all together in a package, it’s a matter of big carrots being placed alongside a waste facility which is less desirable,” said Lake Barrett, a former official at the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) and the DOE. States including Utah and Tennessee have already expressed interest in nuclear energy investments, he said.

The nuclear office said the request had generated interest but did not comment on individual states, which have 60 days to respond. Officials in Utah and Tennessee did not respond to requests for comment.

President Donald Trump wants to quadruple U.S. nuclear power capacity, opens new tab to 400 gigawatts by 2050 as electricity demand surges for the first time in decades thanks to the boom in data centers driving artificial intelligence and the electrification of transport.

In 2025, the DOE picked 11 new advanced nuclear test reactor designs for fast-track licensing and aims to have three pilots built by July 4 this year.

However, public acceptance of nuclear energy hinges partly on the promise of burying nuclear waste deep underground, according to studies by the U.S. and British governments as well as the European Commission.

“A complete nuclear strategy must include safe, durable pathways for final disposition, and that remains a required element of the RFI,” the Office of Nuclear Energy spokesperson said.

Previous efforts to find a solution have run into strong local opposition.

The DOE started looking for a permanent waste facility in 1983 and settled on Nevada’s Yucca Mountain in 1987. But former President Barack Obama halted funding in 2010 due to opposition from Nevada lawmakers worried about safety and the effect on casinos and hotels – with nearly $15 billion already spent.

NEW REACTOR DESIGNS

To accelerate the deployment of nuclear power, countries including the United States, Britain, Canada, China and Sweden are championing so-called small modular reactors (SMRs).

The appeal of SMRs lies in the idea they can be mostly prefabricated in factories, making them faster and cheaper to assemble than the larger reactors already in use.

But none of the new SMR designs are expected to solve the waste problem. Experts say designers are not compelled to consider waste at inception, beyond a plan for how it will be managed.

“This rush to create new designs without thinking about the full system bodes really poorly for effective regulatory oversight and having a well-run, safe, and reliable waste management program over the long term,” said Seth Tuler, associate professor at the Worcester Polytechnic Institute and previously on the U.S. Nuclear Waste Technical Review Board.

Most of the new SMRs are expected to produce similar volumes of waste, or even more, per unit of electricity than today’s large reactors, according to a study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in 2022.

SMRs can also be sited in areas lacking the infrastructure needed for larger plants, raising the prospect of many more nuclear sites which could become interim waste dumps too. And in the United States, “interim” can mean more than century after a reactor closes, according to the U.S. nuclear power regulator.

Reuters contacted the nine companies behind the 11 SMR designs backed by the DOE’s fast-track programme. Some said nuclear waste was an issue for the operators of the reactors, and the government.

Others said they hoped technological advances in the coming decades would improve prospects for reprocessing fuel, although they agreed a permanent repository was still needed.

The prospect of a new wave of nuclear reactors, has rekindled interest in reprocessing spent fuel whereby uranium and plutonium are separated out and, in some instances, reused.

“Modern technologies, particularly advanced recycling and reprocessing, can dramatically shrink the volume of nuclear material requiring disposal,” the spokesperson for the nuclear energy office said. “At the same time, reprocessing does not eliminate the requirement for permanent disposal.”

Nuclear security experts, however, questioned whether reprocessing would be included in any of the new campuses.

“Every time it’s been attempted, it’s failed, it creates security and proliferation risks, the costs are enormous, and it complicates waste management,” said former DOE official Ross Matzkin-Bridger. He said the few countries reprocessing fuel were recycling between zero to 2%, far below the 90% promised.

A PERMANENT PROBLEM

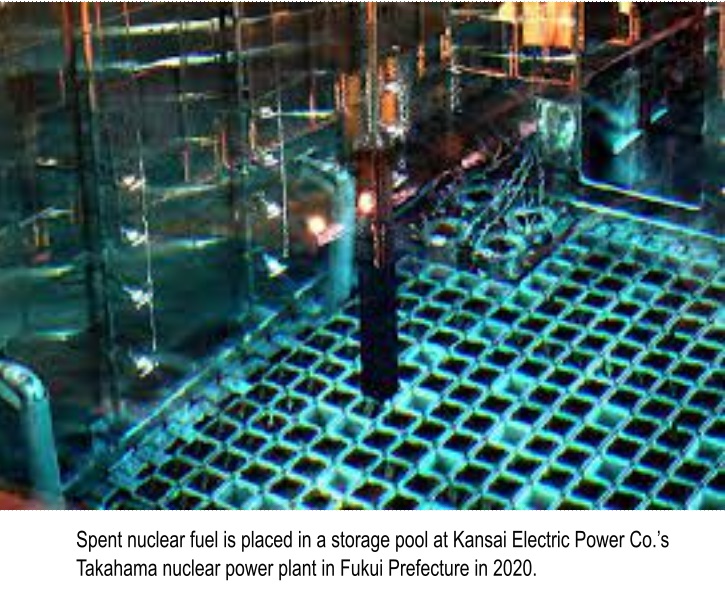

For now, most waste in the United States, Canada, Europe, and Britain is stored on site indefinitely, first in spent fuel pools to cool and then in concrete and steel casks. France sends spent fuel to La Hague in Normandy for reprocessing.

The more than 90 nuclear reactors operating in the United States – the world’s biggest nuclear power producer ahead of China and France – add about 2,000 tons of waste a year to existing stockpiles, according to the DOE.

Office of Nuclear Energy data shows that as of the end of 2024, U.S. taxpayers have paid utility companies $11.1 billion to compensate them for storing spent fuel, some of which can remain harmful to humans for hundreds of thousands of years.

Scotland’s Dounreay site, where the last reactor closed in 1994, has repeatedly extended its decommissioning period and budget due to complications handling waste, according to the British government, in an early sign of the issues the industry faces as older plants shut down.

Vast vaults are being stocked with low-level radioactive waste in large metal containers as Dounreay, once at the cutting edge of Britain’s nuclear industry, is dismantled.

Ever since the first commercial nuclear plant went online 70 years ago in England, the consensus has been that burying the most toxic waste deep underground is the safest option but there is still no repository in operation anywhere in the world.

Getting a repository up and running is a slow process. Governments need community buy-in and geological studies are required to determine the flow of groundwater and the stability of the rock up to 1,000 metres (1,090 yards) underground.

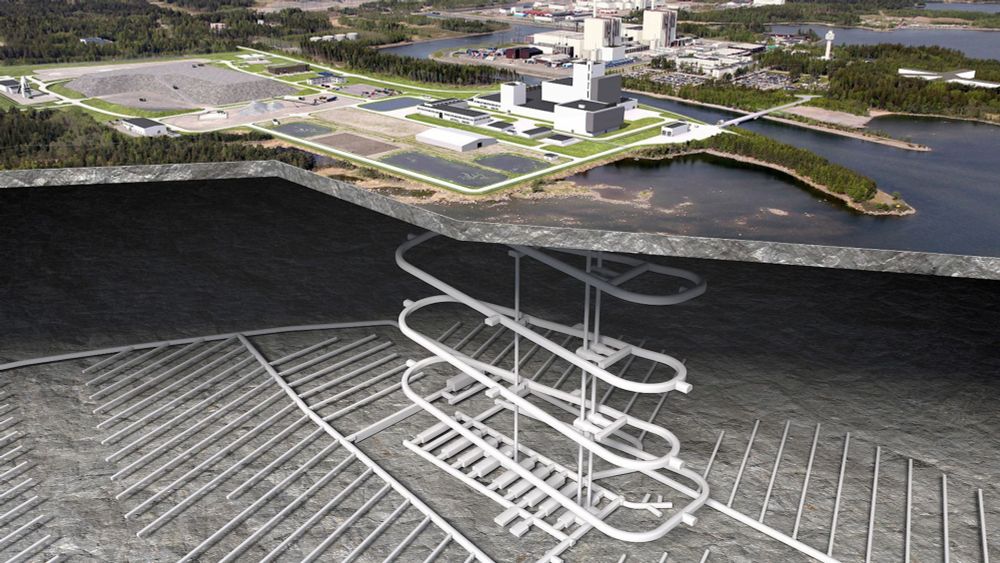

Finland has made the most progress and is close to opening the world’s first permanent nuclear repository in Olkiluoto – having also kicked off the process way back in 1983.

Posiva, the Finnish company behind the project, began transferring test canisters more than four hundred meters below ground in 2024. It told Reuters its goal is to start commercial operations this year, though it is waiting for the Finnish Radiation and Nuclear Safety Authority to approve the operating licence, which will be followed by technical checks.

Once up and running, separate underground tunnels will be filled with canisters made of copper and iron housing the waste, and then sealed forever.

Sweden began constructing its permanent repository in January 2025, aiming to have it running by the late 2030s. Canada has agreed a site in Ontario which it aims to be operational by the late 2040s. Switzerland and France have chosen sites too and hope to have their repositories open from about 2050. Britain is shooting for the late 2050s, but has yet to settle on a location.

Pending the construction of a permanent repository somewhere in the country, high-level waste from nuclear sites such as Dounreay is sent for storage at Sellafield in England.

Some decommissioned nuclear sites, including Dounreay, are also being promoted as locations for data centers, as they’re hooked up to the power grid already and won’t need to wait for a connection.

But the clean-up there has a way to go. Irradiated nuclear fuel was flushed into the sea decades ago and a “minor” radioactive fragment was found on a local beach as recently as January.

The last “significant” particle was found in April and fishing is banned within a 2 kilometer (1.25 mile) radius of Dounreay’s outlet pipe because of radioactive particles on the seabed.

Last year, Britain extended the time frame for the Dounreay clean-up from 2033 to the 2070s.

Reporting by Sarah McFarlane and Susanna Twidale in London, Timothy Gardner in Washington; Visual Production by Morgan Coates; Editing by David Clarke

Northwatch Comments on the NWMO’s Initial Project Description of a Proposed Deep Geological Repository for High-Level Nuclear Waste

7 Feb 26, https://iaac-aeic.gc.ca/050/evaluations/proj/88774/contributions/id/64898

The following points summarize Northwatch’s comments on the NWMO’s Initial Project Description of a Proposed Deep Geological Repository for High-Level Nuclear Waste to be located at the Revell site in Treaty 3 territory in northwestern Ontario:

- NWMO’s Deep Geological Repository Project should be designated for a full impact assessment and public hearing

- The long-distance transportation of nuclear fuel waste from the reactor stations to the proposed repository site must be included in the impact assessment

- NWMO’s Initial Project Description is inadequate and does not provide the information required, including and particularly it does not sufficiently describe or otherwise demonstrate that it has adequately examined alternatives to the project or alternative means of carrying out the project, and the IPD largely goes off course in its description of the need and purpose of the project.

- As directed by the Nuclear Fuel Waste Act the need or purpose of the project is to effectively isolate the nuclear fuel wastes from people and the environment.

- The NWMO has not provided a clear statement of the need and purpose for the project, and when it discussed the need and purpose of the project in its IPD it muddied the waters by including unsupported promotional statements and out-of-scope policy statements about the future role of nuclear power.

- Instead of setting out careful consideration of alternative means of meeting the project need (to safely contain and isolate the nuclear fuel waste from people and the environment) the NWMO simply summarized some aspects of their 2003 studies. The IPD should include a contemporary assessment of alternative means of meeting the project need.

- The NWMO’s consideration of alternative means of carrying out the project is too limited; the alternative means examination should also include alternative sites, alternatives in repository access (ramp vs shaft), transportation in used fuel containers instead of in transportation packages, the alternative means of in-water transfer of used fuel at repository site (vs “in air” ie. in hot cells), alternative mining methods, alternatives in waste emplacement (in-room vs in-floor) and alternatives in used fuel container design

- The NWMO’s description of the project and project activities is too limited, and at times is promotional rather than factual in its approach.

- The NWMO has misrepresented the fuel waste inventory, upon which repository size, years of operation, and resulting degrees of risk and contamination all hinge.

- The NWMO excluded the first step in their project, which is the transfer of the used fuel waste from dry storage containers into transportation containers at the reactor site; this is consistent with past practice.

- Without foundation the NWMO is attempting to exclude long-distance transportation from the Impact Assessment process; this is inconsistent with the impact assessment law in Canada and with the manner in which the NWMO has been describing their project over the last twenty years.

- The Initial Project Description inadequately describes major project components and activities, including the Used Fuel Packaging Plant, waste placement and repository design and construction and closure, decommissioning and monitoring.

- The description of the Project Site, Location and Study Area(s) is flawed and in some respects inaccurate.

- The potential effects of the project are poorly described and in some instances the NWMO text is promotional rather than factual.

- The description of the site selection process is very selective in the information it presents and creates a false impression of community experience through the siting process in the 22 communities that the NWMO investigated.

- There are significant gaps and deficiencies in the Initial project description; several subject areas fundamental to the assessment of the deep geological repository are extremely limited or fully absent including the subjects of long-term safety, emergency response and evacuation plans, accidents and malevolent acts and security.

- The Initial Project Description was poorly organized and was not copy edited; it lacked an index and there was no glossary included.

Decommissioning of Gentilly 1

Ken Collier, 7 Feb 26

As in many industrial projects, many of the hazards come to be known only after the project is well under way or, very often, completed and discontinued. Gentilly 1 is one of those projects. Like others, the Gentilly 1 detritus presents grave dangers to living things as the building, equipment and supplies are taken apart. Complete public review of the decommissioning of Gentilly 1 is required, in my view. It should not be skipped or sidestepped in any way.

Notice of the project was posted on the website of the federal impact assessment agency, but it bears scant resemblance to formal and complete impact assessments, and the public is instructed to send comments to the private consortium, rather than to the federal authorities responsible for making the decision.

To cite Dr. Gordon Edwards, president of the Canadian Coalition for Nuclear Responsibility (CCNR): “Heavily contaminated radioactive concrete and steel would be trucked over public roads and bridges, through many Quebec and Ontario communities, to the Chalk River site just across the Ottawa River from Quebec.”

Impact Assessment of the Planned Dismantling of the Core of the Gentilly-1 reactor.

To: The Honourable Julie Aviva Dabrusin, Minister of Environment and Climate Change

From: The Canadian Coalition for Nuclear Responsibility (CCNR)

Re: Impact assessment of the final dismantling of the Gentilly-1 nuclear reactor

Date: July 5 2026

Reference Number 90092

Cc Impact Assessment Agency of Canada

Atomic Energy of Canada Limited

Canadian Nuclear Laboratories \

Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission

The final dismantling of the most radioactive portions of the Gentilly-1 nuclear reactor, proposed by the licensee Canadian Nuclear Laboratories (CNL), will mark the first time that a CANDU power reactor has ever been fully decommissioned – that is, demolished.

This project is not designated for a full panel review under the Impact Assessment Act (IAA) but you, Minister Dabrusin, have the power to so designate it under the terms of the Act.

The Canadian Coalition for Nuclear Responsibility urges you to do so for the reasons stated below.

(1) When it comes to post-fission radioactivity (human made), the long-lived radioactive decommissioning waste from the core area of a nuclear reactor is second only in radiotoxicity and longevity to the high-level radioactive waste (irradiated nuclear fuel) that has already been designated for a full panel review under IAA at the initiative of NWMO, the Nuclear Waste Management Organization. The deadline for initial comments on the NWMO Deep Geological Repository project (DGR) for used nuclear fuel was yesterday, February 4, 2026. [Our comments: www.ccnr.org/GE_IAAC_NWMO_comments_2026.pdf ]

(2) Fully dismantling a nuclear reactor core is a demanding and hazardous undertaking, resulting in voluminous intermediate level radioactive wastes. The highly radioactive steel and concrete structures – fuel channels, calandria tubes, tube sheet, thermal shield, calandria vessel, biological shield, reactor vault, and more – need to be carefully disassembled, using robotic equipment and perhaps underwater cutting techniques with plasma torches. Such methods are described in a 1984 article published by the Canadian Nuclear Society and linked below, on the detailed advanced methods required for dismantling Gentilly-1.

Gentilly-1 Reactor Dismantling Proposal, by Hubert S. Vogt

Reactor and Fuel Handling Engineering Department

Atomic Energy of Canada Limited – CANDU Operation

Published by the Canadian Nuclear Society in the

Proceedings of the 5th Annual Congress

(3) Dismantling the reactor core will create large amounts of radioactive dust and debris some of which will almost certainly be disseminated into the atmosphere, or flushed into the nearby St. Lawrence River, or added to the existing contamination of the soil and subsoil (including groundwater) at the Gentilly site. It is worth noting that, during the Bruce refurbishment operations in 2009, over 500 workers – local tradesmen, mainly – suffered bodily contamination by inhaling radioactive airborne dust containing plutonium and other alpha emitters (i.e. americium) for a period of more than two weeks. The workers were told that respirators were not required. The radioactivity in the air went undetected for two and a half weeks because neither Bruce managers nor CNSC officers on site took the precaution to have the air sampled and tested.

(4) Once disassembled, the bulky and highly radioactive structural components of Gentilly-1 will have to be reduced in volume by cutting, grinding or blasting. Radioactive dust control and radioactive runoff prevention may be only partially effective. Then the multitudinous radioactive fragments must be packaged, and either (a) stored on site or (b) removed and transported over public roads and bridges, probably to Chalk River. The Chalk River site is already overburdened with high-level, intermediate-level, and low-level radioactive wastes of almost all imaginable varieties. Toxic waste dumping at Chalk River is contrary to the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) and the federal government’s “duty to consult”, since Keboawek First Nation and other Indigenous rights-holders in the area have not given their free, prior, informed consent to either the storage or disposal of these toxic wastes on their unceded territory. A panel review could weigh the options of temporary on-site storage versus immediate relocation. Since there is as yet no final destination for intermediate level wastes, moving those wastes two or three times rather than once (when a final destination exists) will be costlier and riskier. Hence on-site storage is attractive.

(5) The decommissioning waste must be isolated from the environment of living things for thousands of years. The metallic fragments contain such long-lived radioactive species as nickel-59, with a 76,000 year half-life, and niobium-94, with a 20,000 year half-life. The concrete fragments also contain long-lived radioactive species like chlorine-36, with a 301,000 year half-life. Such radioactive waste materials are created during the fission process; they were never found in nature before 1940. NWMO has recommended that such intermediate-level decommissioning waste requires a Deep Underground Repository (DGR) not unlike that proposed for used nuclear fuel. CCNR believes that it is only logical and entirely responsible to call for a panel review of this, the first full decommissioning project for a nuclear power reactor in Canada. The lessons learned will have important ramifications for all of Canada’s power reactors as they will all have to be dismantled at some time. This is not “business as usual”.

Read more: Impact Assessment of the Planned Dismantling of the Core of the Gentilly-1 reactor.(6) Demolition of buildings is often a messy business, but demolition of a nuclear reactor core is further complicated by the fact that everything is so highly radioactive, therefore posing a long-term threat to the health and safety of humans and the environment. A panel review by the Assessment Agency is surely the least we can do in the pubic interest.

(7) To the best of our understanding, Canadian Nuclear Laboratories (CNL) is a private contractor managed by an American-led consortium of multinational corporations, whose work is paid for by Canadian taxpayers through the transfer of billions of dollars to CNL from Atomic Energy of Canada Limited, a crown corporation wholly owned by the Canadian government. As CNL is a contractor, paid to do a job by AECL, CCNR does not feel assured that the best interests of Quebec or of Canada will automatically be fully served by CNL, as it is not accountable to the electorate. When the job involves demolishing, segmenting, fragmenting, packaging and transporting dangerous radioactive materials, involving persistent radiological toxins, we feel that a thorough public review by means of a comprehensive impact assessment, coupled with the involvement and oversight of accountable federal and provincial public agencies is required to ensure that the radioactive inventory is verified and documented, that no corners are cut and no presumptions go unchallenged. The International Atomic Energy Agency strongly advises that before any reactor decommissioning work is done, there has to be a very precise and accurate characterisation of the radioactive inventory –

all radionuclides accounted for, all becquerel counts recorded, and all relevant physical/chemical/biological properties carefully noted. We have seen no such documentation, but we believe it is essential to make such documentation publicly available before final decommissioning work begins, and to preserve such records for future generations so that they can inform themselves about the radioactive legacy we are leaving them. A panel review could help to ensure that we do not bequeath a radioactive legacy that is devoid of useful information, a perfect recipe for amnesia.

(8) The Canadian Coalition for Nuclear Responsibility (CCNR) is federally incorporated as a not-for-profit organization, whose official name in French is le Regroupement pour la surveillance du nucléaire (RSN). CCNR/RSN is a member of le Regroupement des organismes environnementaux en énergie (ROEÉ). The ROEÈ has also filed comments on this dossier, linked below, with 10 recommendations. We endorse the ROEÉ submission and all of its recommendations. The ROEÉ submission is en français www.ccnr.org/IAAC_ROEE_G1_2026.pdf and here is a link to an English translation

www.ccnr.org/IAAC_ROEE_G1_e_2026.pdf .

Yours very truly,

Gordon Edwards, Ph.D., President,

Canadian Coalition for Nuclear Responsibility

Growing stockpiles of radioactive waste beside the Ottawa River upstream of Parliament Hill causing widespread concern.

| The Ottawa River flows through an ancient rift valley that extends from near North Bay through Ottawa toward Montreal. The area is seismically active, and experiences dozens of minor earthquakes each year. Stronger earthquakes also occur such as the magnitude 5 quake in June 2010 that caused shaking, evacuations and damage in Ottawa including shattered windows in Ottawa City Hall and power outages in the downtown area. |

| February 3, 2026The Ottawa River flows through an ancient rift valley that extends from near North Bay through Ottawa toward Montreal. The area is seismically active, and experiences dozens of minor earthquakes each year. Stronger earthquakes also occur such as the magnitude 5 quake in June 2010 that caused shaking, evacuations and damage in Ottawa including shattered windows in Ottawa City Hall and power outages in the downtown area.Experts say Ottawa is at risk for a big earthquake.The Government of Canada is currently in the process of shoring up and earthquake-proofing the buildings on Parliament Hill. The project will take 13 years and cost billions of dollars.Incredibly, at the same time as billions are being spent to earthquake-proof Canada’s Parliament Buildings, the Government of Canada is paying billions of dollars to a US-based consortium that is importing large quantities of radioactive waste to the Ottawa Valley. |

| Soon after it took control of Canada’s nuclear laboratories and radioactive waste in 2015, the consortium, through its wholly-owned subsidiary, Canadian Nuclear Laboratories (CNL), announced its intention to consolidate all federally-owned radioactive waste at Chalk River Laboratories, alongside the Ottawa River, 180 km upstream of the Nation’s Capital. There was no consultation or approval from the Algonquin Nation in whose unceded territory the Chalk River Laboratories is located, nor any consultation with residents of the Ottawa Valley about the plan. |

| CNL is importing nuclear waste from federal nuclear facilities in Manitoba, southern Ontario and Quebec. The imports comprise thousands of shipments and thousands of tonnes of radioactive debris from reactor decommissioning, and dozens of tonnes of high level waste nuclear fuel, the most deadly kind of radioactive waste that can deliver a lethal dose of radiation to an unprotected bystander within seconds of exposure. |

| High level waste shipments from Becancour, Quebec have already been completed. They involved “dozens of trucks” and convoys operating secretly over several months, from December 2024 through July 2025, under police escort, to move 60 tons of used fuel bundles to Chalk River. Tons of high level waste from Manitoba will follow soon. |

| Since there is no long-term facility for high level waste at Chalk River, nor is there any such facility anywhere in Canada at present, CNL built silos (shown in the photo below) to hold the waste at a cost of 15 million dollars. This high level radioactive waste is ostensibly in storage at Chalk River, but there is no guarantee it will ever be moved. |

| CNL plans to put the less deadly waste into a giant, above-ground radioactive waste mound called the Near Surface Disposal Facility, a controversial project currently mired in legal challenges. The dump would hold one million tons of radioactive waste in a facility designed to last about 500 years. Many of the materials destined for disposal in the dump, such as plutonium, will remain radioactive for far longer than that. According to CNL’s own studies, the facility would leak during operation and disintegrate after a few hundred years, releasing its contents to the surrounding environment and Ottawa River less than a kilometer away. |

Shipping containers filled with radioactive waste are piling up at Waste Management Area H on the Chalk River Laboratories property, awaiting a time when they can be driven or emptied into the NSDF. At last count there were 1500 shipping containers there, shown in the photo below. [on original] Source photo is at https://concernedcitizens.net/2025/12/13/cnl-environmental-remediation-management-update-june-2025/

| It would be hard to choose a less suitable place to consolidate all federal radioactive waste than in a seismically-active zone beside the Ottawa River that provides drinking water for millions of Canadians in communities downstream including Ottawa, Gatineau and Montreal. |

| Concerns about imports of radioactive waste to the Ottawa Valley are widespread and growing. |

| In 2021, Ottawa City Council unanimously passed a resolution calling for radioactive waste imports to the Ottawa Valley to stop. Ottawa Riverkeeper recently called for transportation of radioactive waste to the Chalk River Laboratories to stop until a clear, long-term plan for the waste is available. A December 2025 letter to Prime Minister Mark Carney from Bloc Québécois and Green Party MPs along with First Nations and many civil society groups requested a moratorium on shipments of Canadian radioactive waste to Chalk River. |

| Action is urgently needed to halt the imports of radioactive waste to the earthquake-prone Ottawa Valley. |

Slow worms blamed for holding up Britain’s nuclear deterrent

Economists warn project is ‘above budget’ as removal of legless lizards delays expansion.

Jonathan Leake Energy Editor. Matt Oliver Industry Editor,

Rachel Reeves ordered a review of the quango that handles Britain’s nuclear

waste amid concerns about project overruns and spiralling budgets. The

Nuclear Decommissioning Authority (NDA) is in charge of taking apart old

nuclear power stations and storing their radioactive waste securely –

including at Sellafield, the nuclear waste site in Cumbria.

In 2022, a

Treasury report estimated the NDA’s liabilities to be £237bn – a colossal

sum that raised questions over all nuclear spending. The following year,

the Treasury revised that figure down to £124bn simply by applying an

increased discount rate – an accounting device used to reduce the apparent

cost of future spending. Since then, however, costs have jumped again.

In 2024, the National Audit Office found that the budget for Sellafield’s

clean-up had leapt to £136bn.

The new review will be led by Tim Stone, the

chairman of Nuclear Risk Insurers and a former expert adviser to several

government departments. In documents published online, the Department for

Energy Security and Net Zero said the review presented an “opportunity to

address concerns” with the NDA’s performance. They added: “Given the

significance and complexity of the NDA’s task, it is essential to ensure

that the NDA operates effectively and efficiently, delivering value for

money to the taxpayer while also maintaining standards of openness and

transparency.”

Telegraph 27th Jan 2026, https://www.telegraph.co.uk/business/2026/01/27/slow-worms-blamed-for-holding-up-britains-nuclear-deterrent/

Trump offers states a deal to take nuclear waste

POLITICIPRO, By: Sophia Cai | 01/20/2026

The Trump administration wants to quadruple America’s production of nuclear power over the next 25 years and is hoping to entice states to take the nuclear waste those plants produce by dangling the promise of steering massive investments their way.

President Donald Trump’s big bet on amping up nuclear production is not an easy feat, fraught with NIMBY concerns about safety and waste byproducts. The administration hopes to solve at least one of those issues — what to do with toxic nuclear waste — with a program they plan to roll out this week.

Governors would effectively be invited to compete for what the administration believes is a once-in-a-generation economic development prize in exchange for hosting the nation’s most politically and environmentally toxic byproduct.

Energy Secretary Chris Wright has already begun laying groundwork with governors. Over the last two weeks, Wright has met with at least two governors who have expressed interest, according to two officials familiar with the private meetings granted anonymity to discuss them……………………………….(Subscribers only) https://subscriber.politicopro.com/article/2026/01/trump-offers-states-a-deal-to-take-nuclear-waste-00738104

Trump Could Offer Deals to U.S. States to Store Nuclear Waste

Oil Price, By Charles Kennedy – Jan 22, 2026,

The Trump Administration plans to offer U.S. states incentives for building nuclear reactors in exchange for agreeing to store nuclear waste, a source familiar with the matter told Reuters on Thursday.

However, a spokesperson for the U.S. Energy Department told Reuters that the story was “false” and that “no decisions have been made at this time,” after POLITICO first reported on the plan late on Wednesday.

The POLITICO report said that the Energy Department could invite interest from U.S. states as early as this week.

Handling nuclear waste is a politically and environmentally sensitive issue, and the U.S. may have much more of that in the coming years as it the Trump Administration plans to facilitate the expansion of U.S. nuclear energy capacity from about 100 gigawatts (GW) in 2024 to 400 GW by 2050.

The U.S. Administration has bet big on nuclear power, alongside gas, to meet the expected surge in America’s electricity demand driven by AI, data centers, and the onshoring of manufacturing………….

Earlier this month, the Energy Department announced a $2.7 billion investment to strengthen domestic enrichment, in support of President Trump’s commitment to expand U.S. capacity for low-enriched uranium (LEU) and jumpstart new supply chains and innovations for high-assay low-enriched uranium.

Last month, the Energy Department awarded $800 million to TVA and Holtec to advance the deployment of U.S. small modular reactors.

In November, DOE extended a $1-billion loan to help Constellation Energy restart the Three Mile Island Unit 1 nuclear reactor to add baseload power to the grid and help the AI advancement in the United States. https://oilprice.com/Latest-Energy-News/World-News/Trump-Could-Offer-Deals-to-US-States-to-Store-Nuclear-Waste.html

What Canada’s nuclear waste plan means for New Brunswick

by Mayara Gonçalves e Lima, January 20, 2026, https://nbmediacoop.org/2026/01/20/what-canadas-nuclear-waste-plan-means-for-new-brunswick/

Canada is advancing plans for a Deep Geological Repository (DGR) to store the country’s used nuclear fuel. In early 2026, the Nuclear Waste Management Organization (NWMO) entered the federal regulatory process by submitting its Initial Project Description — a major step in a project with environmental and social implications that will last for generations.

The implications of this project matter deeply to New Brunswickers because the province is already part of Canada’s nuclear legacy through the Point Lepreau Nuclear Generating Station. The proposed repository in Ontario is intended to become the final destination for used nuclear fuel generated in New Brunswick, currently stored on site at Point Lepreau.

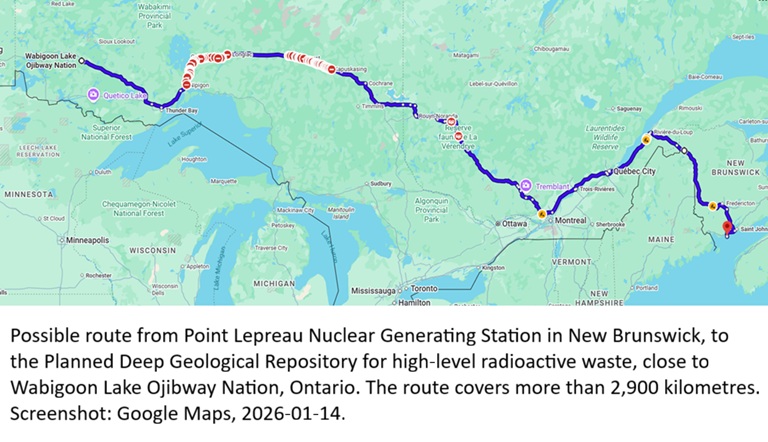

If the project goes ahead, highly radioactive nuclear waste would be transported across New Brunswick. Current NWMO plans envision more than 2,100 transport packages of New Brunswick’s used nuclear fuel travelling approximately 2,900 kilometres, through public roads in the province and across Canada, over a period of 10 to 15 years.

For many residents, the project raises long-standing concerns about safety, accountability, and cost — especially as NB Power continues to invest in nuclear technologies and considers new reactors. Decisions about the DGR will influence how long New Brunswick remains tied to nuclear power, carrying the risks of waste that remains hazardous far beyond any political or economic planning horizon.

This is a critical moment because public input is still possible — but the comment period window is narrow. Environmental organizations and community advocates are calling for extended consultation timelines, full transparency on transport risks, and meaningful consent from affected communities. Several groups have organized a sign-on letter that readers can review and support.

How New Brunswickers respond now will help determine whether these decisions proceed quietly — or with public accountability.

Unproven science and public concerns

Globally, no deep geological repository for high-level nuclear waste has yet operated anywhere on the planet. Finland’s Onkalo facility is often cited as the first of its kind, but it remains in testing, relies on unproven assumptions about geological containment, and will not be fully sealed for decades.

The lack of proven DGR experience matters for Canada because the proposed repository would be among the world’s earliest attempts to isolate high-level radioactive waste “forever,” despite the absence of any real-world proof that such facilities can perform as claimed. Canada’s decision therefore sets not only a national course, but a global precedent built on uncertain science and long-term safety assumptions.

The proposed DGR would be built 650 to 800 metres underground in northwestern Ontario, near the Township of Ignace and Wabigoon Lake Ojibway Nation (WLON), in Treaty #3 territory. Its purpose is to bury and abandon nearly six million bundles of highly radioactive used nuclear fuel, attempting to isolate them from the biosphere for hundreds of thousands of years.

The Nuclear Waste Management Organization describes the site selection as “consent-based,” but this framing raises difficult questions. Consent in economically marginalized regions — particularly where long-term funding, jobs, and infrastructure are promised — is not the same as free, prior, and informed consent, especially when the risks extend far beyond any western planning horizon.

In 2024, the Assembly of First Nations held dialogue sessions on the transport and storage of used nuclear fuel. Communities raised serious concerns that the proposed DGR could harm land, water, and air — all central to Indigenous culture and way of life.

Guided by ancestral knowledge and a duty to protect future generations, the Assembly warned that the DGR threatens sacred sites, ecosystems, and groundwater, including the Great Lakes. Climate change and natural disasters heighten these risks, exposing the limits of the current monitoring plan and prompting calls for life-cycle oversight.

A token consultation for a monumental project

As anticipated, the Initial Project Description raises serious concerns about the DGR process itself. One of the most serious flaws is the stark mismatch between the project’s scale and the time allowed for public input. Although the DGR is framed as a 160-year project with risks lasting far longer, communities, Indigenous Nations, and civil society groups have been given just 30 days to review the Initial Project Description, with submissions due by February 4.

Thirty days to read dense technical documents, consult communities, seek independent expertise, formulate questions, and respond meaningfully to a proposal that will affect land, water, and people for generations. This is not a generous consultation — it is the bare legal minimum under federal impact assessment rules.

While regulators emphasize that the overall review will take years, this early stage is crucial in shaping what will be examined and questioned later. Rushing public input at the outset risks reducing participation to a procedural checkbox rather than a genuine democratic process, particularly for a decision whose consequences cannot be undone.

The overlooked threat of waste transport

Another serious shortcoming in the project proposal is a failure to adequately address the nationwide transport of radioactive waste. Transporting highly radioactive material through communities by road or rail is central to the project and carries significant safety and environmental risks that remain largely unexamined.

By excluding radioactive waste transportation from the Initial Project Description, the Nuclear Waste Management Organization is effectively removing it from the scope of the comprehensive federal Impact Assessment. If transport is not formally included at this stage, it will not receive the same level of environmental review, public scrutiny, or interdepartmental oversight as the repository itself.

Instead, transportation would be left primarily to the Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission and Transport Canada to assess under the existing regulations — an approach that is fragmented and insufficient given the scale, duration, and risks of moving highly radioactive waste through communities.

The transport of radioactive waste is a critical yet often overlooked issue. As Gordon Edwards, president of the Canadian Coalition for Nuclear Responsibility notes, Canada has no regulations specifically governing the transport of radioactive waste — only rules for radioactive materials treated as commercial goods. This gap matters because radioactive waste is more complex, less predictable, and potentially far more dangerous.

Transporting high-level nuclear waste is inherently risky: the material remains hazardous for centuries, and accidents, equipment failures, extreme weather, security breaches, or human error can still occur despite careful planning. Unlike other hazardous materials, radioactive contamination cannot be easily contained or cleaned up, leaving land, water, and ecosystems damaged for generations. Even a single transport incident could have lasting, irreversible consequences for communities along the route.

Radiation risks extend beyond transport workers. People traveling alongside shipments may face prolonged exposure, while those passing in the opposite direction are briefly exposed in much larger numbers. Residents and workers along transport routes can experience repeated exposure, and accidents or unplanned stops could result in localized contamination. Emergency response is further complicated by leaks or hard-to-detect releases, with standard spill or firefighting methods potentially spreading contamination.

These risks are not hypothetical. Last summer, Gentilly-1 used fuel was transported from Bécancour, Quebec, to Chalk River, Ontario, along public roads — without public notice, consultation, Indigenous consent, or clear evidence of regulatory compliance — underscoring the ongoing risks to our communities.

According to the 2024 Assembly of First Nations report, at least 210 First Nations communities could be affected by shipments of radioactive waste traveling from nuclear reactors to the repository via railways and major highways, though the full scope may be even larger when considering watersheds and alternative routes.

Given this reality, it is unacceptable that the DGR Project Description largely ignores waste transport. Any credible assessment must examine how waste will be moved, who will be affected, what rules apply, who is responsible for oversight, and how workers, communities, and the environment will be protected in emergencies. It is the job of the Impact Assessment Agency of Canada to examine these plans in depth.

A high-stakes decision that demands public voice

Canada’s proposed Deep Geological Repository is one of the most ambitious and high-stakes projects in nuclear waste management. Framed as a permanent solution, it remains untested — no country has safely operated a deep repository for used nuclear fuel over the long term. Scientific uncertainty and multi-decade timelines make its risks profound and enduring.

Dr. Gordon Edwards warns: “The Age of Nuclear Waste is just beginning. It’s time to stop and think. […] we must ensure three things: justification, notification, and consultation — before moving any of this dangerous, human-made, cancer-causing material over public roads and bridges.”

Now is the moment for public voices to be heard. Legal Advocates for Nature’s Defence (LAND), an environmental law non-profit, has prepared a sign-on letter and accompanying press release calling for a more precautionary, transparent, and democratic approach to the Deep Geological Repository. This is your chance to have a say in decisions that could expose you, your neighbours, and your communities to serious environmental and health risks.

The letter urges federal regulators to extend public consultation timelines, require that the Impact Assessment Agency of Canada conduct a comprehensive Impact Assessment that includes the transportation of radioactive waste, and uphold meaningful consent and accountability.

New Brunswickers and allies across the country are encouraged to read the letter, add their names, and speak up before decisions are finalized. How Canada handles nuclear waste today will shape risks borne by our communities for generations.

The DGR is more than a technical project; it is a test of democratic process, scientific caution, and intergenerational responsibility. Canadians deserve a transparent, thorough, and precautionary approach to ensure that decisions made today do not compromise the safety of future generations.

Mayara Gonçalves e Lima works with the Passamaquoddy Recognition Group Inc., focusing on nuclear energy. Their work combines environmental advocacy with efforts to ensure that the voice of the Passamaquoddy Nation is heard and respected in decisions that impact their land, waters, and future.

Summary comments on the Deep Geologic Repository (DGR) Project for Canada’s Used Nuclear Fuel

The nuclear waste will be radioactive for, say, a period of time that is close to eternity, whereas the project covers a period of 160 years. The solution is therefore very far from permanent.

We are swimming here in the middle of a pro-nuclear religion.

by Miguel Deschênes, 20 Jan 26

a translation of comments submitted in French to the Impact Assessment Agency of Canada (IAAC) by Miguel Deschêne on this subject.

Seven major objections stand out:

1- Developers are not trustworthy

On page v of the document, it states that “Canada’s nuclear power plants have been providing clean energy for decades,… ». Then, on page vii, it is explained that the project itself “would contain and isolate approximately 5.9 million spent fuel assemblies,” representing approximately 112,750 tonnes of irradiated and highly radioactive heavy metals. This waste contains a wide variety of radioactive substances that are dangerous to living beings. One of the most famous isotopes found in these spent fuel bundles is plutonium-239. Need we remind you that Canadian plutonium was used in the bomb that destroyed the city of Nagasaki in 1945? To say on page v of the document that nuclear energy is clean and to specify on page vii that it will generate 112,750 tonnes of highly radioactive (and potentially destructive) heavy metals in Canada is staggering incoherent.

On page iv of the document, there is a list of twelve specialists and managers who prepared, reviewed, approved and accepted this document, which includes this glaring logical error. This leads to the conclusion that the developers seem willing to present all possible arguments, however incongruous, to defend this project, while concealing the negative aspects that could overshadow it. They therefore have neither the capacity for reflection nor the objectivity required to manage this project, when it would be essential to protect the safety of the public and the environment in complete transparency.

2- The objective(s) are unattainable

The document presents the objective of the project in two places, but they are two different objectives. These objectives look strangely like advertising slogans or the creeds of a pro-nuclear cult. Neither is attainable in practice, but they make it easy to project yourself into a world of unicorns:

a- On page viii, it is stated that: “The objective of the Project is to ensure the safe long-term management of used nuclear fuel so that it does not pose a risk to human health or the environment.”

We are talking about guaranteeing, for 160 years. A great Quebec poet would say “it’s better to laugh than to cry.” A car, which is one of the most advanced technological objects on the planet, is guaranteed for 3 or 5 years. How can we believe that we can guarantee a new landfill technology for a period of 160 years? It’s simply delusional.

In addition, even a simple plastic bottle carries risks to human health or the environment. And they want us to believe that this project will make it possible to store 112,750 tonnes of radioactive nuclear waste so that it does not pose any risk to human health or the environment? What sensible person can believe such a statement?

b- On page 20, it states that: “The objective of the Project is to provide a permanent, safe and environmentally responsible solution for the management of all of Canada’s used nuclear fuel.”

The nuclear waste will be radioactive for, say, a period of time that is close to eternity, whereas the project covers a period of 160 years; The solution is therefore very far from permanent. The solution is also presented as safe and environmentally friendly: based on what? The solution is safe as long as it is sold by convinced developers, but everyone knows that it involves enormous risks. And environmentally friendly? How can we say that burying 112,750 tonnes of radioactive nuclear waste is an environmentally friendly solution? We are swimming here in the middle of a pro-nuclear religion.

Obviously, neither of these two objectives is achievable in practice.

What is the real objective of the project? Indirectly extract as much money as possible from the public treasury and taxpayers? Putting hundreds of highly paid employees to work unnecessarily for decades? Shovel the problem of nuclear waste to our descendants?

The project is therefore, even before it has begun, doomed to failure, since it is impossible for it to achieve its totally utopian objectives. To believe in the success of this project, it is absolutely necessary to be overwhelmed by the pro-nuclear faith.

3- The budget is not presented

On page 52, it states that “Federal authorities are not providing any financial support to the Project.”

On page 65, it states that: “In addition, although the NWMO is a regulated entity by the CNSC, it is not a federal agency or authority. Rather, it is a question of a not-for-profit organization mandated by the federal government under the NFCA to managing Canada’s nuclear waste. The NWMO is fully funded by industry nuclear power. »

However, the Government of Canada and some provincial governments subsidize and financially encourage the nuclear industry.

So, in a nutshell, taxpayers are giving money to governments, which in turn subsidizes the nuclear industry, and which in turn funds the NWMO. The present project is therefore indirectly financed by taxpayers and by the federal authorities, which is not revealed by the sentence on page 52. Could we conclude that it is not necessary to call on an accountant if you have a good conjurer?

A detailed budget is one of the essential elements of project planning and monitoring. Where is the budget? How is it cut? And how much will it indirectly cost taxpayers? It would be reasonable to describe the sums required as potentially pharaonic and to require a project plan that includes a complete financial plan.

The absence of a budget in the presentation of a project is an unacceptable shortcoming.

4- The project’s time scale is doubly absurd

On page v, it states that “The Project is expected to span approximately 160 years, including site preparation, construction, operation (approximately 50 years), decommissioning and closure, and post-closure monitoring.”

This duration is both too short and too long:

a- Too short: the half-life of plutonium-239 is about 24,130 years. It is calculated that after a duration of approximately seven times the half-life of an isotope, less than 1% (more precisely, 1/128) of the initial radioactive atoms remain. In the case of plutonium-239, it would therefore be necessary to wait about 168,000 years to reach this target. Obviously, this calculation would have to be done for all the isotopes found in the original waste and for all the isotopes created during subsequent decays in order to properly assess the hazardousness of the waste as a function of time, which is very complex. But we can see right away that the 160-year period is far too short to ensure the safety of the public and the environment.

b- too long: if we go back 160 years in time, we find ourselves in 1866, when the Canadian federation did not even exist. Since that time, humanity has experienced various epidemics (plague, cholera, Spanish flu, covid, etc.), two world wars and a multitude of other wars, major geopolitical reorganizations and major economic crises. It is perfectly utopian to think that a human project that has no other objective than to bury waste will be able to be carried out without hindrance for 160 years. What happens if there is a major epidemic, a world war, a coup d’état by an outsized geographic neighbour, a split in Canada, an unforeseen IT upheaval? How can we seriously believe that all the governments and political parties that will succeed each other will have at heart, for 160 years (if each party remains in power for 4 years, we are talking about 40 different governments), to adequately supervise this project?

In general, the longer a project lasts, the greater the likelihood of not achieving objectives, exceeding costs and exceeding the originally planned schedule. It is therefore quite reasonable and prudent to predict that the 160-year deep geological repository project is likely to be a complete failure: it will not achieve its objectives, while exceeding the planned deadlines and costs.

5- The responsibility for the project in the medium and long term cannot be assumed

What will be the responsibility for the project in the medium and long term, i.e. in 10, 20, 50 or 100 years? What if there is a design problem, a technical problem, a supplier problem, a funding problem, a nuclear incident or whatever? Who will be responsible when most of us are dead? To whom can our descendants turn to ask for accountability and rectification if necessary? No one can imagine or predict it, and it is likely that any assumption today about it will prove wrong tomorrow.

6- The risks associated with transportation are far too high

No means of transportation is perfectly safe. Regularly, planes crash, trains derail (the Lac-Mégantic rail accident in 2013 is a sad example) and trucks are involved in pile-ups. Sometimes, a space shuttle explodes in mid-flight.

On page vii, it states that “The Project does not include: the transportation of used fuel from the reactor sites to the Project beyond the primary and secondary access roads to the Project site, as the Project site is regulated separately under CNSC certification and uses existing transportation infrastructure.”

This seems to be, once again, a tactic to make the authorities and citizens swallow the pill of the project. The risks associated with a possible incident during the transportation of 112,750 tonnes of high-level radioactive waste on Canada’s roads, over a period of about fifty years (according to the projected schedule on page 31), are obviously far too high. It is therefore easy to understand why the developer prefers not to include this aspect in his project.

The excessive risk associated with transporting radioactive waste is an argument used by the Nuclear Waste Management Organization itself on its information page about Canada’s used nuclear fuel (https://www.nwmo.ca/fr/Canadas-used-nuclear-fuel): “Related questions: Couldn’t spent nuclear fuel be sent into space? No. In a three-year dialogue with experts and the public on possible long-term management options, the disposal of used nuclear fuel into space was one of the options of limited interest that we eliminated. Space-based evacuation has been ruled out as a solution because it is an unproven concept, not implemented anywhere in the world and not part of any national research and development plan. Concerns about the risk of accidents and the risks to human health and the environment have been amplified in particular by the accidents of the American space shuttles Challenger and Columbia. »

Why should the risk of an accident not be a consistent factor in the Nuclear Waste Management Organization’s reasoning? There have certainly been more train derailments and truck accidents than space shuttle incidents in human history. By what form of logic can we conclude that it is too risky to send used nuclear fuel into space, but that it is safe to transport it by train or truck? The only plausible explanation may be that we must have pro-nuclear faith.

7- Governments do not have a strategy to exit the nuclear industry

On page vii of the document, it states that: “The Project would contain and isolate approximately 5.9 million used fuel assemblies, which is the total anticipated inventory of used nuclear fuel that is expected to be produced in Canada by the current fleet of reactors until the end of their lifetime, as outlined in the NWMO’s 2024 Nuclear Fuel Waste Projections Report (NWMO, 2024). This projection is based on published plans for the refurbishment and life extension of the Darlington and Bruce reactors, as well as the continued operation of the Pickering A (until the end of 2024) and Pickering B (until the end of 2026) reactors, and the assumptions used by the NWMO for planning purposes. »

However, in October 2025, Ottawa and Ontario announced the construction of 4 new nuclear reactors (https://ici.radio-canada.ca/nouvelle/2201625/darlington-nucleaire-reacteur-opg-ontario). What about the waste that will be generated by these plants, which is not part of the inventory considered by the project? And what about those generated by other hypothetical power plants to come? Or those that the government could import from other countries?

Successive governments are constantly creating, recreating and amplifying the problem of nuclear waste, with no intention of ending this mess. The only decision that would limit this ecological disaster would be to abandon the nuclear industry, which would include stopping uranium mining, no longer building new nuclear power plants and never importing nuclear waste from other countries. Unfortunately, no decision-maker seems to have the foresight to move in this direction.

Even before the project begins, we already understand that the planned landfill will not be able to store all of Canada’s nuclear waste. Without a clear direction on the denuclearization of the country, the problem of radioactive waste is far from being solved.

In any case, a deep geological repository will never be a good solution for nuclear waste; This far too risky avenue is really only used to shovel the problems created by today’s decision-makers until a time when they will all be dead and will not have to assume the disastrous consequences.

Conclusion :

In my view, these arguments are more than enough to justify never authorizing the Deep Geologic Repository (DGR) Project for Canada’s used nuclear fuel. It seems that the “original project description” seeks to conceal the real issues related to nuclear waste management, in order to obtain the required authorizations, spend obscure (but potentially staggering) amounts of money, and perpetuate nuclear madness, with no regard for public safety and the environment. Unfortunately, this is a typical project of the nuclear industry, which relies on the blind complacency of the authorities and on daydreams rather than on transparency and objective arguments.

Ontario’s proposed nuclear waste repository poses millennia-long ethical questions

Maxime Polleri, Assistant Professor, Université Laval, January 16, 2026 , https://theconversation.com/ontarios-proposed-nuclear-waste-repository-poses-millennia-long-ethical-questions-273181

The heat produced by the radioactive waste strikes you when you enter the storage site of Ontario Power Generation at the Bruce Nuclear Generating Station, near the shore of Lake Huron in Ontario.

Massive white containers encase spent nuclear fuel, protecting me from the deadly radiation that emanates from them. The number of containers is impressive, and my guide explained this waste is stored on an interim basis, as they wait for a more permanent solution.

I visited the site in August 2023 as part of my research into the social acceptability of nuclear waste disposal and governance. The situation in Ontario is not unique, as radioactive waste from nuclear power plants poses management problems worldwide. It’s too dangerous to dispose of spent nuclear fuel in traditional landfills, as its radioactive emissions remain lethal for thousands of years.

To get rid of this waste, organizations like the International Atomic Energy Agency believe that spent fuel could be buried in deep geological repositories. The Canadian government has plans for such a repository, and has delegated the task of building one to the Nuclear Waste Management Organization (NWMO) that’s funded by Canadian nuclear energy producers.

In 2024, NWMO selected an area in northwestern Ontario near the Township of Ignace and the Wabigoon Lake Ojibway Nation as a potential site for a deep geological repository. Now, a federal review has begun bringing the project closer to potential reality.

Such repositories raise complex ethical questions around public safety, particularly given the millennia-long timescales of nuclear waste: How to address intergenerational issues for citizens who did not produce this waste but will inherit it? How to manage the potential dangers of these facilities amid short-term political cycles and changing public expectations?

While NWMO describes the deep geological repository as the safest way to protect the population and the environment, its current management plan does not extend beyond 160 years, a relatively short time frame in comparison with the lifespan of nuclear waste. This gap creates long-term public safety challenges, particularly regarding intergenerational ethics. There are specific issues that should be considered during the federal review.

NWMO argues that the deep geological repository will bring a wide range of benefits to Canadians through job creation and local investment. Based on this narrative, risk is assessed through a cost-benefit calculus that evaluates benefits over potential costs.

Academics working in nuclear contexts have, however, criticized the imbalance of this calculus, as it prioritizes semi-immediate economic benefits, like job creation, over the long-term potential impacts to future generations.

In many official documents, a disproportionate emphasis on short-term economic benefits is present over the potential dangers of long-term burial. When risks are discussed, they’re framed in optimistic language and argue that nuclear waste burial is safe, low risk, technically sound and consistent with best practices accepted around the world.

This doesn’t take into account the fact that the feasibility of a deep geological repository has not been proven empirically. For the federal review, discussions surrounding risks should receive an equal amount of independent coverage as those pertaining to benefits.

Intergenerational responsibilities and risks

After 160 years, the deep geological repository will be decommissioned and NWMO will submit an Abandonment License application, meaning the site will cease being looked after.

Yet nuclear waste can remain dangerous for thousands of years. The long lifespan of nuclear waste complicates social, economic and legal responsibility. While the communities of Ignace and Wabigoon Lake Ojibway Nation have accepted the potential risks associated with a repository, future generations will not be able to decide what constitutes an acceptable risk.

Social scientists argue that an “acceptable” risk is not something universally shared, but a political process that evolves over time. The reasons communities cite to decide what risks are acceptable will change dramatically as they face new challenges. The same goes for the legal or financial responsibility surrounding the project over the centuries.

In the space of a few decades, northwestern Ontario has undergone significant municipal mergers that altered its governance. Present municipal boundaries might not be guarantees of accountability when millennia-old nuclear waste is buried underground. The very meaning of “responsibility” may also undergo significant changes.

NWMO is highly confident about the technical isolation of nuclear waste, while also stating that there’s a low risk for human intrusion. Scientists that I’ve spoken with supported this point, stating that a deep geological repository should not be located in an area where people might want to dig.

The area proposed for the Ontario repository was considered suitable because it does not contain significant raw materials, such as diamonds or oil. Still, there are many uncertainties regarding the types of resources people will seek in the future. It’s difficult to make plausible assumptions about what people might do centuries from now.

Communicating long-term hazards

When the repository is completed, NWMO anticipates a prolonged monitoring phase and decades of surveillance. But in the post-operation phase, there is no plan for communicating risks to generations of people centuries into the future. The long time frame of nuclear materials complicates the challenges of communicating hazards. To date, several attempts have surrounded the semiotics of nuclear risk; that is, the use of symbols and modes of communication to inform future generations.

For example, the Waste Isolation Pilot Plan in New Mexico tried to use various messages to communicate the risk of burying nuclear waste. However, the lifespan of nuclear waste vastly exceeds the typical lifespan of any known human languages.

Some scientists even proposed a “ray cat solution.” The project proposed genetically engineering cats that could change color near radiation sources, and creating a culture that taught people to move away from an area if their cat changed colour. Such projects may seem outlandish, but they demonstrate the difficulties of developing pragmatic long-term ways of communicating risk.

Current governing plans around nuclear waste disposal have limited time frames that don’t fully consider intergenerational public safety. As the Canadian federal review for a repository goes forward, we should seriously consider these shortcomings and their potential impacts on our society. It is crucial to foster thinking about the long-term issues posed by highly toxic waste and the way it is stored, be it nuclear or not.

This Nuclear Renaissance Has a Waste Management Problem

12 Jan, 26, https://energyathaas.wordpress.com/2026/01/12/this-nuclear-renaissance-has-a-waste-management-problem/

Three sobering facts about nuclear waste in the United States.

Americans are getting re-excited about nuclear power. President Trump has signed four executive orders aiming to speed up nuclear reactor licensing and quadruple nuclear capacity by 2050. Big tech firms ( e.g. Google, Amazon, Microsoft, Meta) have signed big contracts with nuclear energy producers to fuel their power-hungry data centers. The federal government has signed a deal with Westinghouse to build at least $80 billion of new reactors across the country. Bill Gates has proclaimed that the “future of energy is sub-atomic”.

It’s easy to see the appeal of nuclear energy. Nuclear reactors generate reliable, 24/7 electricity while generating no greenhouse gas emissions or local air pollution. But these reactors also generate some of the most hazardous substances on earth. In the current excitement around an American nuclear renaissance, the formidable challenges around managing long-lived radioactive waste streams are often not mentioned or framed as a solved problem. This problem is not solved. If we are going to usher in a nuclear renaissance in this country, I hope we can keep three sobering facts top-of-mind.

Fact 1: Nuclear fission generates waste that is radioactive for a very long time.