“Selling a dream”: the French nuclear start-up that ran aground

Naarea’s unravelling provides cautionary tale for dozens of small reactor

developers racing to bring designs to fruition.

In December 2023 the founder of French nuclear start-up Naarea gathered employees and investors

in Paris for a black-tie dinner and dance at which it revealed a large

model of the mini reactor it hoped would revolutionise the world of energy.

The gala capped an ebullient year for the group after it scored €10mn in

public subsidies and encapsulated the verve of its chief executive Jean-Luc

Alexandre, according to people who know him and a person who attended the

party.

Then came a cash squeeze and a brutal unravelling. The six-year-old

company, which had pledged to start rolling out reactors by the start of

the next decade, is now a step away from a court-managed liquidation.

The downfall of Naarea — “Nuclear Abundant Affordable Resourceful Energy

for All” — comes as more than 100 nuclear ventures around the world

race to bring their designs for small reactors to fruition. Yet the

technical challenges of some projects, and the huge funding many will need

to withstand years without revenues, are becoming increasingly apparent.

Earlier experiments with microreactors were largely abandoned in the 1970s

as the atomic energy industry sought economies of scale by moving towards

much bigger plants, including in France, home to Europe’s biggest fleet of

57 nuclear power stations.

FT 26th Feb 2026, https://www.ft.com/content/a782639d-1ac1-4252-a7ef-e8052925bbce

Small modular nuclear reactors for developing countries: Expectations and evidence Open Access

Friederike Friess , Maha Siddiqui , M V Ramana, PNAS Nexus, Volume 5, Issue 2, February 2026,

https://academic.oup.com/pnasnexus/article/5/2/pgag006/8419276

Abstract

Many developing countries have shown interest in acquiring nuclear power plants, particularly small modular reactors (SMRs). By analyzing presentations made by national representatives at International Atomic Energy Agency conferences, we identified 3 key expectations of SMRs expressed by many officials: that they generate electricity at low cost, that the design be demonstrated through operating experience elsewhere, and that there be potential for local manufacturing associated with the nuclear power project.

However, based on the available evidence regarding SMR designs, we demonstrated that these expectations are unlikely to be fulfilled.

SMRs do not benefit from economies of scale, unlike large nuclear power plants. Because electricity from large nuclear plants is expensive, SMRs will produce more costly power.

Second, it is unrealistic to expect that SMRs will qualify as proven technology in the near future because of the very limited number of SMRs currently in operation or under construction. The performance of currently operating SMRs has also been underwhelming.

Finally, the idea of local manufacturing conflicts with the proposed economic model of mass production. At the same time, the skilled local workforce needed to operate these reactors is not readily available in many newcomer countries.

U.S. Tech Park in Israel May Have a Nuclear Power Plant

While President Trump has busted through a lot of international norms, and removed the U.S. from multilateral agreements like climate change, busting the bounds of the Nonproliferation Treaty would set a dangerous precedent that could be followed by similar actions by Russia and China

The fact that Israel has signed an MOU with the U.S. that could potentially involve it acquiring U.S. manufactured SMRs is a signal that if India can do it, so can Israel. Saudi Arabia will not be far behind in asking for the same deal should the Israeli industrial park agreement move forward beyond the MOU stage.

February 7, 2026 by djysrv, https://neutronbytes.com/2026/02/07/u-s-tech-park-in-israel-may-have-a-nuclear-power-plant/

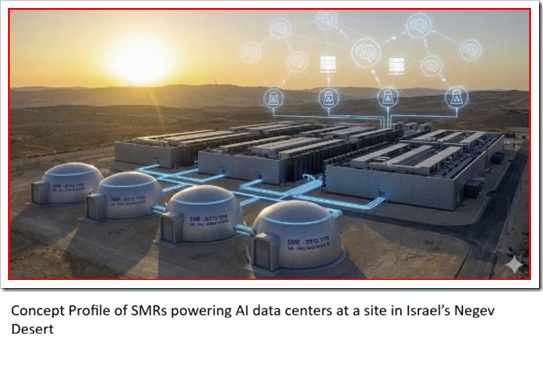

Israel signed an agreement with the U.S. on 01/16/26 to build an industrial park to produce advanced computer chips at a location in the Negev desert that would use a small modular nuclear reactor (SMR) to power the factory and nearby data centers also planned for this location.

Where things stand now, according to Israel news media, Israel and the US have inked an agreement to jointly build and operate a large technological park in Israel. The deal is part of a strategic cooperation agreement on AI signed in Jerusalem last month. (Israel government statement)

One of the surprising details to emerge from the discussions on the agreement relates to the energy infrastructure. The huge power demands of data centers and AI computer systems require a large, reliable 7/24/365 energy solution. As a result, the possibility appears to be kicking around of constructing one or more nuclear power plants, most likely SMRs, at the site.

The MOU, signed by the head of the National AI Directorate, Brig. Gen. (Res.) Erez Eskel, and the U.S. Under Secretary of State for Economic Affairs Jacob Helberg, reveals an ambitious plan to allocate 4,000 acres to the U.S. The park, which will be constructed in the Negev Desert or less likely in the Gaza Strip border area, and which will be called “Fort Foundry One”

Helberg travelled to Israel after signing similar agreements in Doha and Abu Dhabi. He said that Israel was an “anchor partner” in the effort, thanks to its technological ecosystem and its ability to produce “asymmetric results” in relation to its geographical size.

US Under Secretary of State for Economic Affairs, Jacob Helberg said, “With the launch of Pax Silica, the United States and Israel are uniting our innovation ecosystems to ensure the future is shaped by strong and sovereign allies leading in critical technologies like AI and robotics.”

Helberg comes to his role as a former lobbyist for Silicon Valley information technology firms and as a former executive for Google. One of his key interest areas has been addressing the national security risks posed to the U.S. by China. He wrote a book on the subject, The Wires of War: Technology and the Global Struggle for Power, (2021) calling for a stronger U.S. strategy against China’s technological ambition. According to the publisher’s book jacket, Helberg led Google’s global internal product policy efforts to combat disinformation and foreign interference in U.S. domestic affairs.

U.S. Thinks a Contractual Fig Leaf Can Cover the Absence off a 123 Agreement

Israel to date has no experience with civilian nuclear power plants used for electricity generation. The country has reportedly produced an unspecified number of nuclear weapons used as a deterrence factor when dealing with hostile neighbors like Iran. Also, Israel has not signed the Nuclear Nonproliferation Treaty due to policy of strategic ambiguity and its obvious reluctance to reveal the extent of its nuclear arsenal.

The official MOU for the Negev AI data center remains somewhat vague referring to a “high-intensity energy infrastructure” but it clearly is pointing to small modular reactors (50-300 MW). Due to the location in the extremely dry Negev desert, an advanced design, such as an HTGR, which does not require cooling water to operate, is likely to be chosen should the project reach a stage where a reactor design would be selected for this site.

The joint initiative is part of a broad international framework launched by the Trump administration called “Pax Silica“, a coalition of about twelve countries in technology, the aim of which is to secure supply chains of semiconductors and AI. Taiwan did not sign the agreement.

Israel joined the initiative in December 2025, and was the first country to sign a bilateral agreement with the U.S. in this framework. Among the other countries in the coalition are Qatar, the UAE, Australia, Greece, Japan, South Korea, Singapore, and United Kingdom.

The Heavy Lift Associated with Civilian Nuclear Power in Israel

Israel has abundant natural gas supplies to support private wire gas power generation for data centers. It doesn’t need small modular reactors to power them.

The geopolitical heavy lift that would be required for a civilian nuclear power plant in Israel would probably set off a similar request from Saudi Arabia for the same kind of deal.

The Saudi government has been stalled for years in its quest for US nuclear reactors due to its insistence on the right to uranium enrichment as part of a 123 Agreement with the U.S. The Saudi government sees enrichment as a deterrence signal to Iran over its nuclear program. If the U.S. gives a green light to Israel, through some kind of three bank policy pool shot, to build U.S. supplied civlian SMRs, without a 123 Agreement, the Saudis would likely ask for a similar deal.

While President Trump has busted through a lot of international norms, and removed the U.S. from multilateral agreements like climate change, busting the bounds of the Nonproliferation Treaty would set a dangerous precedent that could be followed by similar actions by Russia and China.

This would move the planet into dangerous territory. For this reason, consideration of a U.S. managed nuclear power plant in Israel may be too hot a potato for even Trump to toss over the transom. Bipartisan opposition in the Senate would be almost certain for a civilian nuclear reactor deal with Israel without a 123 agreement.

Israel does not have an agreement with the U.S. under Section 123 of the Atomic Energy act as such a move would require it to declare its nuclear infrastructure. The Israeli government has relied on strategic ambiguity about how many nuclear devices it has as a deterrence measure. The Israeli government is not going to give that up military advantage away to get small modular reactors to power data centers in a white collar industrial park.

Finally, the news release by the Israeli Prime Minister’s office about the U.S. deal may be one of a series of trial balloons the Israeli government has floated over the years about civilian nuclear power so it should be viewed with some skepticism for that point alone.

The U.S. plan apparently is to cover these issues with a contractual fig leaf that depends on a unique model in which the reactor operates under U.S. safety regulation and supervision, despite being located on Israeli territory. It’s a pretty thin leaf.

Watch What We Do Not What We Say

It is not lost on the Saudi and Israel governments that India enjoys a special relationship regarding recent developments that open the door to India for acquisition of civilian U.S. nuclear reactor technologies, without having a 123 Agreement, while these two nations are locked out these opportunities.

Where things get complicated is that the Saudi government has undoubtedly been watching how U.S. nuclear reactor firms are faring with India for some time. Recently, India opened the door to U.S. nuclear reactors by terminating its supplier liability law that acted very effectively as a trade barrier for U.S. firms.

Almost at the same time, the U.S. Department of Energy granted Holtec permission to export its 300 MW SMR to India. The authorization names three Indian companies – Larsen & Tubro (Mumbai), Tata Consulting Engineers (Mumbai) and the Company’s own subsidiary, Holtec Asia (Pune) – as eligible entities with whom Holtec can share necessary technical information to execute its SMR-300 program. Holtec also plans to build a factory in India to manufacture the small reactors. Westinghouse is expected to seek to enter the Indian nuclear market.

What the Saudi government sees is that U.S. policy towards India shows a remarkably different approach to a country which has declared it has a nuclear arsenal, has tested its nuclear weapons, and is not a party to the Nonproliferation Treaty. Further, India does not have a 123 agreement with the U.S. and has no immediate plans to seek one. Israel has likely come to the same point of view.

The fact that Israel has signed an MOU with the U.S. that could potentially involve it acquiring U.S. manufactured SMRs is a signal that if India can do it, so can Israel. Saudi Arabia will not be far behind in asking for the same deal should the Israeli industrial park agreement move forward beyond the MOU stage.

Saudi Plans for AI Data Centers Points to Nuclear Reactor to Power Them

The Saudi government’s ambitious plans and programs to transform the oil rich company into a regional powerhouse for artificial intelligence will require significant investments in electricity generation to power the AI data centers needed to carry out this effort.

According to a report in the New York Times, Saudi Arabia is investing $40 billion to become a dominant player for the use of AI in the Middle East. Data centers to support this program will require enormous amounts of electrical power to support the advanced semiconductors that process AI software, to power the data centers themselves, and to keep them cool in one of the hottest regions on the planet.

It follows that the Saudi government will coordinate its plans for a nuclear new build with its massive investments in AI. It is likely that sooner or later Saudi Arabia’s need to break ground on the first two reactors in anticipation of the need for power for its AI program and related data centers.

It may decide that building commercial nuclear power plants to power its AI program is more important than the geopolitical consideration of having access to nuclear technologies with or without a U.S. 123 Agreement. Given the U.S. course of actions with India, Saudi Arabia may ask for the same kind of deal thus bypassing the entire enrichment policy issue it has with the U.S.

The Saud government has a tender outstanding, which has been on hold for some time, to build two 1,400 MW PWR type reactors. It has also explored options for SMRs for data centers and to power desalination plants to provide potable water for general and industrial uses. A award for the two reactors could be the first order of business the Saudi government will seek to pursue in asking for the same deal the U.S. gave India.

Germany: Ministry of the Environment: Mini‑reactors [SMNRs] not an option

Berlin (energate) – The gap between the hype and industrial reality surrounding nuclear energy is widening. This applies in particular to the smaller nuclear reactors, Small Modular Reactors (SMR). This is the conclusion of the World Nuclear Industry Status Report, which was commissioned by the Heinrich Böll Foundation, the Federal Office for the Safety of Nuclear Waste Management (BASE) and the Friedrich Ebert Foundation, among others.

by Leonie Wolf, energate, 22 January 2026

According to the study, nuclear energy remains “irrelevant” on the global market, as the 5.4

GW increase in nuclear capacity is offset by 100 times the combined new capacity of over 565

GW of wind and solar energy. Wind and solar plants

worldwide currently generate 70 per cent more electricity than nuclear reactors.

According to the report, there is still no market-ready product for Small Module Reactors (SMR), only a design certification and an approved standard design. Both come from the US company NuScale. The US Nuclear Regulatory Commission has already approved a total of three of the company’s models, but previous contracts with potential customers have been cancelled due to increased costs.

A first mini-reactor was cancelled in 2023.

According to the study, the two largest European start-ups Newcleo and Naarea are in financial difficulties; the French start-up Naarea has already filed for insolvency. The start-up is now to be taken over by the Polish-Luxembourgish group Eneris.

The Netherlands and France continue to rely on nuclear power

Despite these failures, other countries are sticking with nuclear energy. In the Netherlands, a debate on the use of SMR, which is seen as a measure to achieve the 2030 climate targets, has been ongoing for several years. In addition, the Dutch company Mammoet signed a memorandum of understanding with Electricité de France (EDF) at the end of 2025, which provides for the construction of nuclear plants in the Netherlands. Two nuclear power plants were already planned for 2022 and two more are still in operation.

Debate continues in Germany

Although Germany has withdrawn from nuclear energy, the debate about its benefits continues. Parliamentary State Secretary Rita Schwarzelühr-Sutter also spoke at the presentation of the World Nuclear Industry Status Report. When asked by energate, a spokesperson for the Federal Ministry for the Environment explained that Germany had “good reasons” for withdrawing from the use of nuclear power. The risks of nuclear energy and also of the use of SMRs remain “ultimately unmanageable”. In addition, the development and construction of smaller reactors raises many other unresolved issues.

There is also no reliable evidence to date for the safety promises. As a result, the disadvantages of nuclear energy would be transferred from a few large plants to many small ones. Ultimately, “the individual plants may become smaller, but the problems as a whole tend to become bigger”.

The spokesperson also referred to a study by the Federal Office for the Safety of Nuclear Waste Management, which energate has already reported on. According to the report, the advantages of mass production of SMRs would only outweigh their fundamental cost disadvantages compared to large reactors with a production volume of around 3,000 units.

The CDU/CSU (Christian Democrats) parliamentary group takes a different view. At the end of 2024, the CDU and CSU published a position paper in which they advocated research and development of nuclear power plants, including SMRs. CSUChairman Markus Söder also spoke out in favour of the use of SMRs in an interview with Die Welt at the end of 2025.

A total of 127 different designs worldwide

The report states that it is above all the continuous financial and political support for SMRs that keeps faith in them alive. In particular, private capital injections are playing an increasingly important role in driving research and development forward. There are 127 different SMR designs, so the funding amounts are widely spread. This means that most designs do not have sufficient financial resources to drive development forward

. According to the report, even the US start-up NuScale is still years away from building the first Small Module Reactor, although several designs have already been approved.

Trump slashing nuclear reactor safety and security rules

January 29, 2026, https://beyondnuclear.org/trump-slashing-reactor-safety-and-security-rule

Department of Energy executes White House Executive Order

Radical changes to nuclear safety and security at new reactors withheld from public review

In response to White House Executive Order 14301 issued on May 23, 2025, the US Department of Energy (DOE) is deregulating federal reactor safety /security standards and rules in order to expedite at least three experimental designs of eleven new advanced reactors. The DOE cuts are intended to speed up licensing, construction and operational testing phase so as to achieve reactor criticality by July 4, 2026. The expedited approval process will be used to demonstrate proof-of-product for full commercial operation of these designs as ready for mass assembly line production.

National Public Radio (NPR) reported on January 28, 2026, that it had obtained copies of the DOE documents as the basis for their news story headlined “The Trump administration has secretly rewritten nuclear safety rules.” The new rules and standards for reactor safety and security of unproven experimental reactor designs have not yet been publicly released. As NPR reports, the new rules are being rewritten to alter 5o years of duly promulgated regulatory law by the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) not to bolster public safety, national security and environmental protection but to hasten the deployment of unproven, untested and still dangerous nuclear power technology.

In an earlier NRC interview on December 17, 2025. Dr. Allison Macfarlane, a former NRC Chairwoman, warned that the federal government cannot both commercially promote nuclear power and independently regulate nuclear safety and security with reasonable assure a very low probability of the next severe nuclear accident or by deliberate malice. On numerous occasions, Dr. Macfarlane, other NRC Commissioners and independent scientists point to an established historical conflict of interest created by federal government and nuclear industry’s simultaneous collaborative promotion and regulatory expansion of nuclear power and nuclear arms race.

That proved to be the downfall of the US Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) principally established for the development of atomic bombs and cogenerate electricity from the waste heat from the weaponization of the atom. The AEC was subsequently abolished by Congress with the passage of the Energy Reorganization Act of 1974 (ERDA) because of gross neglience of nuclear safety. On January 19, 1975, the AEC responsibilities were divided up creating the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission to take over the safety licensing and regulation of commercial nuclear power and the Energy Research and Development Agency (ERDA) to handle energy research, development, and the functions of nuclear weapons production. ERDA was later incorporated into the US Department of Energy in 1977.

The United States has now come full circle with the Trump Administration’s executive orders dismantling 50 years of promulgation of nuclear power safety regulation and regulatory law to return safety to the back seat and nuclear energy promotion as the priority. It is further alarming and no secret that several of the new commercial reactor designs under licensing review by the DOE are in fact “dual purpose” reactors that once operational will have the capability to produce both electrical energy and the basic building blocks for nuclear weapon enhancement and expansion.

The January 28th NPR analysis finds that DOE’s nuclear rules “slash hundreds of pages of requirements for security at the reactors. They also loosen protections for groundwater and the environment and eliminate at least one key safety role. The new orders cut back on requirements for keeping records, and they raise the amount of radiation a worker can be exposed to before an official accident investigation is triggered.”

Where the protection of groundwater from radioactive contamination once was required as a “must,” the new DOE rules and standards need only provide “‘consideration’ to ‘avoiding or minimizing’ radioactive contamination. Radioactive monitoring and documentation are also softened,” NPR observed.

An independent scientist is quoted in the NPR story, “They’re taking a wrecking ball to the system of nuclear safety and security regulation oversight that has kept the U.S. from having another Three Mile Island accident,’ said Edwin Lyman, director of nuclear power safety at the Union of Concerned Scientists. ‘I am absolutely worried about the safety of these reactors.’”

Now here we are, during the 50th anniversary of the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission, the Trump Administration, the DOE and the nuclear industry are poised for “Unleashing American Energy” by deregulatory Executive Orders.

The DOE announced the “Reactor Pilot Program” in June 2025, following the release of Executive Order 14301, which accelerates and expands the federal experimental reactor testing program to streamline commercial reactor licensing and oversight. At the same time, the Trump Administration is deregulating the NRC by slashing its safety and security standards and regulatory law.

The DOE “Pilot Reactor Program” is comprised of eleven projects. The DOE will choose at least three units to be licensed for operational criticality by July 4, 2026:

- Aalo Atomics Inc.—The Austin, Texas-based startup nuclear company has broken ground for its experimental 10 MWe sodium cooled reactor under development at the Idaho National Laboratory near Idaho Falls, Idaho. Five units are intended to make up a 50 MWe “pod” for electrical power production.

- Antares Nuclear Inc.— Headquartered in Los Angeles, California, Antares Nuclear has submitted a construction permit application filed for a four-unit, non-power, light-water-cooled, pool-type Versatile Isotope Production Reactor facility to be located at the Idaho National Laboratory desert site, in Bingham County, Idaho.

- Atomic Alchemy Inc.—Atomic Alchemy Inc. is headquartered in Idaho National Laboratory, Idaho Falls, Idaho. The company operates in the nuclear technology sector, specifically focused on non-power radioisotope production reactors for the defense, industrial and medical sectors using the 15-MWtVersatile Isotope Production Reactor (VIPR).

- Deep Fission, Inc.— The start-up company is headquartered in Berkeley, CA for the development of a 15 MWe pressurized water microreactor that first broke ground in Parsons, Kansas on December 9, 2025. It is proposed as a first-of-a-kind deep geological reactor at the Great Plains Industrial Park in Labette County on the Kansas-Oklahoma border. Deep Fission signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with its “sister” company Deep Isolation to collocate the power generation facility in a mile deep 30 inch wide borehole in the bedrock. The natural bedrock body and a mile deep column of water overhead are credited for the reactor containment system. The same borehole and bedrock body are credited as a permanent, deep geological high-level radioactive waste disposal facility. After seven years of operation, the reactor vessel is disconnected from the surface turbogenerator and control room and abandoned, capped and sealed in place in-place at the bottom of the borehole. The next fresh fuel loaded reactor unit is lowered down the borehole and connected to the surface to resume operation stacked on top of the now sealed unit nuclear waste unit. And so on.

- Last Energy Inc.—Last Energy Inc. corporate headquarters are in Austin, Texas. The start-up company is proposing to build a fleet of 20-MWe micro-modular reactors near Abilene, Texas targeting data center power needs (specifically the PWR-20, a downsized model of the currently operational commercially sized Point Beach reactor Unit 1 rated at 625 MWe in Wisconsin).

- Oklo Inc. (two projects)— Oklo Inc. is headquartered in Santa Clara, California. Its Aurora Powerhouse is a 75 MWe small modular liquid sodium-cooled fast reactor under development at the Idaho National Laboratory. Oklo is additional developing an estimated $1.7 billion project to build the nation’s first privately funded nuclear fuel recycling facility at the Oak Ridge Heritage Center in Tennessee. This project aims to recycle used nuclear fuel from existing reactors into fuel for fast reactors, with operations targeted for 2030. The proposed fast reactors are identified as a global nuclear weapons proliferation risk to be exported around the world.

- Natura Resources LLC— Natura Resources is headquartered in Abilene, Texas. The company is developing a Generation IV liquid-fueled molten salt reactor (MSR). They are proposing to site their first reactor at the Science and Engineering Research Center (SERC) on the campus of Abilene Christian University in Abilene, Texas.

- Radiant Industries Inc.— Radiant Industries is headquartered in El Segundo, California for modular microreactors. Radiant has announced that it will build its first microreactor factory on a decommissioned Manhattan Project site in Oak Ridge, Tennessee. World Nuclear News reports, “Radiant is developing the 1 MWe Kaleidos high-temperature gas-cooled portable microreactor, which will use a graphite core and TRISO (tri-structural isotropic) fuel. The electric power generator, cooling system, reactor, and shielding are all packaged in a single shipping container, facilitating rapid deployment.”

- Terrestrial Energy Inc.— Terrestrial Energy, Inc. is headquartered in Charlotte, North Carolina. They are developing the Integral Molten Salt Reactor (IMSR) which is a Generation IV small modular reactor (SMR) designed to produce both high-grade industrial heat and electricity. Their pilot project is planned for the Texas A&M University RELLIS Campus in Bryan, Texas.

- Valar Atomics Inc.— Valar Atomics Inc. is headquartered in El Segundo, California. The company is developing the Ward 250, a 100-kWt, helium-cooled, TRISO-fueled high-temperature gas reactor (HTGR) designed for modular, behind-the-meter, or microgrid use. The pilot project is located at the Utah San Rafael Energy Lab (USREL) in Emery County, Utah.

Small Modular Reactors: Game changer or more of the same?

There has been a large amount of publicity on Small Modular Reactors (SMRs) based on exaggerated, unproven or untrue claims for their advantages over large reactors. Only one order for a commercially offered design has been placed (Canada) and that had yet to start construction in January 2026. The UK should not invest in SMRs until there is strong evidence to support the claims made for them.

Policy Brief, Stephen Thomas, Emeritus Professor of Energy Policy, Greenwich University, 31 Jan 26 https://policybrief.org/briefs/small-modular-reactors-game-changer-or-more-of-the-same/

Introduction

With current large reactor designs tarnished by their poor record of construction, attention for the future of new nuclear power plants has switched to Small Modular Reactors (SMRs). The image of these portrayed in the media and by some of their proponents is that they will roll off production lines, be delivered to the site on the back of a truck and, with minimal site assembly, be ready to generate in next to no time; they will be easy to site, a much cheaper source of power, be safer and produce less waste than large reactors; as a result, they are being built in large numbers all around the world. But what is the reality?

What are SMRs and AMRs?

In terms of size, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) defines SMRs as reactors producing 30-300MW of power and defines reactors producing up to 30MW as micro-reactors. In practice, the size of SMRs is increasing and of the seven designs that have received UK government funding, four are at or beyond the 300MW upper limit for SMRs.1 The vendors of the two micro-reactor designs funded by the UK have both collapsed,2 leaving the X-Energy Xe-100 the only reactor design, at 80MW, that is technically an SMR.

The term Advanced Modular Reactor (AMR) is largely a UK invention and denotes reactors using designs other than the dominant large reactor technologies — Pressurised and Boiling Water Reactors (PWRs and BWRs). In other countries, the term SMR covers all reactors in the IAEA’s size range. None of the proposed AMR designs are new, all having been discussed for 50-70 years but not built as commercial reactors. They can be divided into those built as prototypes or demonstration reactors — the Sodium-cooled Fast Reactor (SFR) and the High Temperature Gas-cooled Reactor (HTGR) — and those that have not been built — Molten Salt Reactors (MSRs) and Lead-cooled Fast Reactors (LFRs).

Some designs include a heat storage device so that when demand is high, this heat can be used to generate additional electricity as well as that generated by the reactors. When electricity demand is low, the heat produced by the reactor can be stored for when demand is higher, giving it a generating flexibility. For example, the Terrapower SFR design includes molten salt heat storage to boost the station’s output from 345MW to 500MW at peak times. This is intended to address the issue that operating reactors in ‘load-following mode’ is problematic technologically and economically. It is not clear whether this generating flexibility justifies the substantial additional expense of the heat storage system.

What is the case for SMRs and AMRs?

SMRs and AMRs are presented, not only by the nuclear industry, but also by the media and government, as established, proven, commercial products. The main claims for SMRs and AMRs compared to large reactors are:

- They will be cheaper to build per kW of capacity and less prone to cost overruns;

- They will be quicker and easier to build and less prone to delay;

- They will produce less waste per kW of capacity;

- Building components on factory production lines will reduce costs;

- Modular construction, reducing the amount of site-work, will reduce costs and delays;

- They will be safer;

- They will generate more jobs.

There have been numerous critiques that demonstrate these claims are at best unproven or at worst simply false.3 The summary of the critiques on each point is as follows.

Construction Cost

The first commercial reactors worldwide were mostly in the SMR size range, but they proved uneconomic and the vendors continually increased their size to gain scale economies, culminating in the 1600MW Framatome European Pressurised Reactor (EPR). Intuitively, a 1600MW reactor vessel will cost less than ten 160MW reactor vessels. While increasing their size was never enough to make the reactors economic, it is implausible that scaling them down will make them cheaper per unit of capacity because of the lost scale economies. It appears that SMRs are struggling to be economically viable. Holtec doubled the electrical output of its design at some point in 2023.4 The realistic competitors to SMRs are not large reactors but other low-carbon options such as renewables and demand-side management.

“While increasing their size was never enough to make the reactors economic, it is implausible that scaling them down will make them cheaper per unit of capacity because of the lost scale economies.”

Construction time

There is no clear analysis explaining why reactors are now expected to take longer to build and why they seem more prone to delay.5 However, it seems likely that the issue is that the designs have got more complex and difficult to build as they are required to take account of vulnerabilities exposed by events such as the Fukushima disaster. The problems thrown up by the occupation of Ukraine’s Zaporizhia site by Russia have yet to be taken up in new reactor designs. As a result of the 9/11 terrorist attack on New York, new reactor vessels are required to be able to withstand an aircraft impact. The conflict in Ukraine spilled on to the Zaporizhia site causing concerns that a serious accident would result. Analysis suggests that the exterior of other parts of the plant should be toughened. If the issue is complexity rather than size per se, reducing the size of the reactors may do no more than make construction a little easier.

Waste

For SMRs, there is a clear consensus that they will produce more waste per unit of capacity than a large reactor. For example, Nuclear Waste Services, the UK body responsible for waste disposal said: “It is anticipated that SMRs will produce more waste per GW(e) than the large (GW(e) scale) reactors on which the 2022 IGD data are based.”6 Alison MacFarlane, former chair of the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) wrote: “The low-, intermediate-, and high-level waste stream characterization presented here reveals that SMRs will produce more voluminous and chemically/physically reactive waste than LWRs, which will impact options for the management and disposal of this waste.”7 The AMRs will produce an entirely different cocktail of waste varying according to the type of reactor.

“SMRs will produce more voluminous and chemically/physically reactive waste than Large Light Water Reactors”

Factory production lines

In principle and in general, production lines, which have high set-up costs, can reduce costs with high-volume items with a fixed design and a full order book. But, if demand is not sufficient to fully load the production line or the design changes requiring a re-tooling, the fixed costs might not be fully recoverable. The production lines proposed for SMRs will produce less than a handful of items per year — a long way from a car or even an aircraft production line — and the market for SMRs is uncertain, so guaranteeing a full order book is impossible. There is also a ‘chicken and egg’ issue that the economics of SMRs will only be demonstrated when the components are produced on production lines, but production lines will only be viable when the designs are demonstrated sufficiently to provide a flow of orders.

Modularity

Modularity is a rather vague term, and all reactors will be made up of components delivered to the site and assembled there, any difference between designs being down to the extent of site work. The Westinghouse AP1000 design is said to be modular but this did not prevent all eight orders suffering serious delays and cost overruns. Framatome now describes the successor design to the EPR, the 1600MW EPR2, as modular.8

Safety

Some of the SMRs and AMRs rely on ‘passive’ safety, in other words, they do not require the operation of an engineered system to bring the reactor back under control in the event of an accident. A common assumption is that because it is passive, it is fail-safe, and will therefore not require back-up safety systems and so will be cheaper. None of these assumptions is true and, for example, the UK Office of Nuclear Regulation (ONR) has said for the 20MW PWR design from Last Energy: “ONR advised that it is philosophically possible to rely entirely on two passive safety systems, providing there is adequate defence in depth (multiple independent barriers to fault progression)”.9 Some designs rely on being built underground but the Nuward and NuScale designs that use this have struggled to win orders with Nuward being abandoned and NuScale losing its only major order prospect because of rising costs.10

Job creation

A key selling point for SMRs is that they will require much less site work and that implies fewer jobs. More of the work will be done in factories but the business model for SMRs requires that, globally, as few factories be built as possible to maximise scale economies, so if, for example, the factory is not in the UK, neither will the jobs be.

What is the experience with SMRs?

Many reactors that fall into the size range of SMRs were built in the 1960s including 24 reactors in the UK. By the mid-60s, almost all new orders were for reactors larger than 300MW. This century, only two SMR projects have been completed11, one in China and one in Russia, but neither design appears to have any firm follow-up projects. Two projects are under construction, one in Russia and one in China, but neither design appears to have any further firm order prospects. There is one micro-reactor under construction in Argentina (see Table below).

The most advanced project using a commercially available design is for a GE Vernova BWRX-300 reactor to be built at the Darlington site in Canada. There appears to be a firm order for this reactor although by January 2026, construction had not started. The Canadian safety regulator will assess the design during the construction period, not before construction starts as would be required in most jurisdictions; this gives rise to a risk of delays and cost escalation if a design issue requiring additional cost emerges during construction.

There are several other projects with a named site and design, often presented in the media as being under construction, but these have yet to receive regulatory approval for the design, they do not have construction permits and a firm reactor order has not been placed. Those listed in Table 1 are the ones that appear most advanced in terms of regulatory approvals. Numerous other projects have been publicised, invariably with ambitious completion date targets, but they are some distance from a firm order being placed. Up to this point, historically, a high proportion of nuclear projects of all sizes announced do not proceed and there is no reason to believe this will not be the case with these projects. Once a firm reactor order has been placed, the project is more likely to go ahead because the cost of abandonment is high.

The two operating SMRs (in China and Russia) have a very poor record in terms of construction time and operating performance, but authoritative construction costs are not known. Completion of the three under construction is also behind schedule. While these projects are not for commercial designs, this provides no evidence that the ambitious claims for SMRs will be met.

Conclusions

The perception that SMRs are being built in large numbers is untrue and the claims made for them in terms of, for example, cost, safety, and waste are at best unproven and at worst false.

The image of them being much smaller than existing reactors is incorrect. The IAEA’s size range is arbitrary but the clear trend for SMRs to increase in size does put a question mark against the claims made for them such as reduced cost per kW due to small size, ease of siting and mass production. Most of the designs that have realistic order prospects are at or beyond the 300MW upper limit of the IAEA range for SMRs. This is illustrated by the Holtec design which, for more than a decade was being developed as a reactor, SMR160, designed to produce 160MW of electricity. In 2023 and with no publicity, the output of the reactor was doubled to become the SMR300 and projects using this technology are foreseeing 340MW of power. The idea that siting and building them will be easy is not credible; a reactor of more than 300MW will need to be carefully sited so it is not vulnerable to sea-level rise or to seismic issues and will require substantial on-site work including foundations, suggesting that the claim that these projects would be largely factory built is implausible. It would also mean that either the modules would be very large making them difficult to transport or would require a larger number of modules increasing the amount of site-work.

“The perception that SMRs are being built in large numbers is untrue and the claims made for them in terms of, for example, cost, safety, and waste are at best unproven and at worst false.”

This increased size also means that the image of a rolling production line producing large numbers of reactors is inaccurate. Rolls Royce, whose design has increased to 470MW, is anticipating its production lines would produce components for only two reactors per year.

The UK, along with Canada and the USA is in the vanguard of development of SMR designs. The history of nuclear power shows that developing new reactor designs is an expensive venture with a high probability of failure. The UK’s chosen design is the largest SMR design on offer and is being developed by a company with no experience designing or building civil nuclear power plants. Submarine reactors have very different design priorities and the reactors built by Rolls Royce use US designs. There is huge scope for the UK to build much cheaper offshore wind and to carry out energy efficiency measures which would have the double dividend of reducing emissions and tackling fuel poverty. It would make much more sense for the UK to let other countries make the investments and take the risk and only if SMRs are shown to fulfil the claims made for them to then adopt them as part of the UK’s generating mix.

| Country | Site | Vendor | Technology | Output MW | Status | Construction start | Commercial operation | Load factor |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Russia | Lomonsov | Rosatom | PWR | 2 x 32 | Operating | April 2007 | May 2020 | 32.1% |

| Russia | Brest | Rosatom | SFR | 300 | Under construction | June 2021 | 2028/29 | |

| China | Shidoa Bay | Tsinghua | HTGR HTR-PM | 200 | Operating | December 2012 | December 2023 | 26.9% |

| China | Linglong 1 | CNNC | PWR ACP100 | 100 | Under construction | July 2021 | 2026? | |

| Argentina | Carem25 | CNEA | PWR Carem | 25 | Under construction | August 2015 | 2028? | |

| Canada | Darlington | GE Vernova | BWRX-300 | 300 | Firm order | – | 2030? | |

| USA | Kemmerer | Terrapower | SFR Natrium | 345 | Construction permit applied for | – | 2031? | |

| USA | Palisades | Holtec | PWR SMR300 | 2 x 340 | Pre-licensing | – | 2030? | |

| USA | Clinch River | GE Vernova | BWRX-300 | 300 | Construction permit applied for | – | 2033? | |

| UK | Wylfa | Rolls Royce | PWR | 470 | Design review | 2030? | 2035? | |

| UK | Llynfi | Last Energy | PWR | 4 x 20 | Site licence applied for | 2028? | 2030? |

Note: Load factor is the most widely used measure of reactor reliability and is measured as the electrical output of the plant as a percentage of the output produced if the reactor had operated uninterrupted at full power.

Endnotes…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

There’s a lot of hype around small modular reactors.

From Steve Thomas, Emeritus Professor of Energy Policy, University of Greenwich, London SE10, UK, 30 Jan 26 https://www.ft.com/content/085e92e6-2f7f-4381-9416-0aa59fa3a3

Richard Ollington (“Small nuclear reactors are worth the wait”, Opinion, January 16) makes three claims. First, that small modular reactors (SMRs) will get quicker and easier to build, citing the French programme as evidence. Second, Russia is building large numbers of SMRs and third, improving existing reactors and reviving retired ones could add 40GW of nuclear capacity. None of these claims stands up to scrutiny. Over the 15 years of the French programme, the real cost of reactors increased by some 60 per cent. Construction of the first eight reactors averaged 70 months while the last eight averaged 135 months.

Russia has completed only two SMRs and has one under construction. The two completed ones are barge-mounted reactors providing heat and power to an isolated Siberian community. They took 13 years to build and have a reliability of 40 per cent. Restarting two retired reactors (1.6GW), one owned by Meta, the other by Microsoft, is actively being considered, but awaits approval from the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission before decisions can be taken to bring them back to life. The increasing concentration of carbon in the atmosphere will not wait a decade to see if the ambitious claims for SMRs are met. So even if we were to believe the hype surrounding SMRs, we cannot afford to wait to see if they prove viable.

The Reality of SMR Timelines for AI Data Centers: A Veteran’s View

Nov 2,2025, By Tony Grayson, Tech Executive (ex-SVP Oracle, AWS, Meta) & Former Nuclear Submarine Commander

If you’ve been following the recent nuclear boom, you’ve seen the headlines: Amazon commits to 5 GW. Google signs for advanced reactors. Oracle announces gigawatt-scale campuses. The message is clear: nuclear is the solution.

There is just one problem: GPUs move in 3-year cycles. Reactors move in decades.

I spent my early career commanding nuclear submarines, where “downtime” wasn’t a metric; it was a mission failure. Later, I built data center infrastructure for Oracle, AWS, and Meta. I know the difference between a PowerPoint slide and a commissioned plant. I know what it takes to cool a reactor core versus a Blackwell rack……..

Below is the reality check on SMR timelines for AI data centers, HALEU fuel shortages, and what infrastructure buyers should actually do.

SMR Timelines for AI Data Centers: The Executive Summary

To optimize for decision-making, we must look at the specific delivery windows. Here is the realistic availability for nuclear power sources.

- Near-Term (2025–2029): Reactor Restarts

- Status: Feasible but limited.

- Timeline: 3–5 years.

- Examples: Palisades (Michigan) or Three Mile Island Unit 1.

- Constraint: These require existing sites in good condition with willing local stakeholders.

- Medium-Term (2030–2035): Gen III+ Large Reactors

- Status: Proven technology, difficult execution.

- Timeline: 10–14 years.

- Constraint: The Vogtle Units 3 & 4 (AP1000) proved that even “off-the-shelf” designs can take a decade and cost $30B+.

- Long-Term (2035–2045): Advanced SMRs (Gen IV)

- Status: Experimental supply chain.

- Timeline: Factory scaling likely post-2035.

- Constraint: HALEU fuel availability and lack of factory fabrication lines.

If your strategy relies on SMR timelines for AI data centers intersecting with your 2028 capacity needs, you are missing the target.

The HALEU Fuel Gap: The Supply Chain That Doesn’t Exist

The biggest risk to the “Advanced Nuclear” narrative is not the reactor; it is the fuel.

Many Gen IV designs (like TerraPower’s Natrium) require HALEU (High-Assay Low-Enriched Uranium).

- The Demand: The DOE projects we need >40 metric tons by 2030.

- The Supply: Current U.S. capacity is negligible (less than 1 ton/year).

- The Problem: Prior to 2022, Russia was the primary commercial supplier.

Until domestic enrichment scales, a process that involves centrifuges, licensing, and billions in CAPEX…Gen IV SMRs have no fuel……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. https://www.tonygraysonvet.com/post/nuclear-power-for-ai-datacenters

Trump’s rush to build nuclear reactors across the U.S. raises safety worries

NPR, December 17, 2025

In May, President Trump sat in the Oval Office flanked by executives from America’s nuclear power industry.

“It’s a hot industry. It’s a brilliant industry,” the president said from behind the Resolute desk.

It’s also an industry that’s having a moment. Billions of dollars in capital are currently flowing into dozens of companies chasing new kinds of nuclear technologies. These are small modular designs that can potentially be mass produced in the hundreds or even thousands. Their proponents say these advanced designs promise to deliver megawatts of power safely and cheaply.

But there’s a problem, Joseph Dominguez, the CEO of Constellation Energy, told the president.

New nuclear plants keep getting caught up in safety regulations.

“Mr. President, you know this because you’re the best at building things,” Dominguez, whose company runs about a quarter of America’s existing nuclear reactors, said. “Delay in regulations and permitting will absolutely kill you. Because if you can’t get the plant on, you can’t get the revenue.”

Now, a new Trump administration program is sidestepping the regulatory system that’s overseen the nuclear industry for half a century. The program will fast-track construction of new and untested reactor designs built by private firms, with an explicit goal of having at least three nuclear test reactors up and running by the United States’ 250th birthday, July 4, 2026.

If that goal is met, it will be without the direct oversight of America’s primary nuclear regulator. Since the 1970s, safety for commercial reactors has been the purview of the Nuclear Regulatory Commission. But the NRC is only consulting on the new Reactor Pilot Program, which is being run by the Department of Energy’s Office of Nuclear Energy……………………………………………………………………………………………………

Sites across the country will host new reactor designs

The new pilot program may be an unproven regulatory path run by an agency with limited experience in the commercial sector, but supporters say it’s energizing an industry that’s been moribund for decades.

“This is exactly what we need to do,” said Isaiah Taylor, founder and CEO of Valar Atomics, a small nuclear startup headquartered in Hawthorne, Calif. “We need to make nuclear great again.”

Valar and other companies plan to build smaller reactors than those currently used in the nuclear industry, and that makes a Chernobyl or Fukushima-type accident impossible, noted Nick Touran, an independent nuclear consultant. “The overall worst-case scenario is definitely less when you’re a smaller reactor,” he said.

Critics, however, worry that the tight July 4 deadline, political pressure and a lack of transparency are all compromising safety. Even a “small” release of radioactive material could cause damage to people and the environment around the test sites.

“This is not normal, and this is not OK, and this is not going to lead to success,” warned Allison Macfarlane, a professor at the University of British Columbia who served as chairman of the NRC under President Barack Obama. “This is how to have an accident.”

AI’s need for speed

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………. Right from the start it was clear that, unlike the slow and deliberate safety culture that has dominated nuclear power for decades, this new program would be all about speed.

…………officials responsible for overseeing safety would do “whatever we need to ensure that the government is not stopping you from reaching [nuclear] criticality on or before July 4, 2026.”

A new regulator

Before the executive order, the Energy Department did not regulate the safety of commercial nuclear reactors. That job fell to another body: the Nuclear Regulatory Commission.

The commission was set up in 1975 by Congress as an independent safety watchdog, said Allison Macfarlane, the former NRC chair. Part of the reason the NRC was formed was because the predecessor to the DOE, known as the Atomic Energy Commission, oversaw both safety and promotion of nuclear power at the same time.

“This was a very strong conflict of interest,” Macfarlane said.

But in recent years, companies, particularly those trying to build new kinds of reactors, had become frustrated with the NRC, Macfarlane said. “The promoters of these small modular reactors were becoming very vociferous about the NRC being the problem,” she said.

In 2022, the NRC rejected a combined license application for Oklo, a new nuclear startup. Oklo had submitted an application to build and operate its small reactor, called the Aurora powerhouse. But the NRC denied the application because it contained “significant information gaps in its description of Aurora’s potential accidents as well as its classification of safety systems and components.”

Oklo was told it could resubmit its application to the NRC, but it never did.

Then at the May signing of the executive order, Oklo’s CEO Jacob DeWitte appeared behind President Trump applauding the new reactor program at DOE.

“Changing the permitting dynamics is going to help things move faster,” DeWitte said to the president. “It’s never been more exciting.”

Oklo had another connection to the Energy Department — the secretary of energy, Chris Wright, was a member of Oklo’s board of directors until he took the helm at the DOE. Wright stepped down following his confirmation in February.

In August, a little over a month after that initial meeting between industry executives and the DOE, the Office of Nuclear Energy announced the 11 advanced reactor projects had been selected for the Reactor Pilot Program. Three of Oklo’s reactors were part of the new pilot program, including a test version of the reactor design rejected by the NRC…………………………………………………………………………………………………………

Valar’s design looks far different from the reactors that are running today. It will use a special type of fuel together with a high-temperature gas to generate heat and electricity. Taylor said gathering real data will speed development and increase safety over the long-term….

(Valar is also party to a lawsuit against the NRC arguing the commission does not have the authority to regulate small reactors. In his interview, Taylor told NPR the company intends to file for an NRC license “when we’re ready.”)

………………………………………………….. critics question whether the pilot program will really produce safe nuclear reactors.

The July 4, 2026, deadline puts enormous pressure on the program, said Heidy Khlaaf, the chief AI scientist at the AI Now Institute, which recently published a report warning that AI development could undermine nuclear safety.

“I think these manufactured timelines are actually incredibly concerning,” Khlaaf said. “There’s no timeline for assessing a new design and making sure it’s safe, especially something we haven’t seen before.”

Then there’s the question of public transparency. The NRC makes many of the documents around its decisions available publicly. It also frequently allows the public to comment as well, added Edwin Lyman, director of nuclear power safety at the nonprofit Union of Concerned Scientists. The new pilot program is far more opaque and “is really an attempt to subvert the laws and regulations that go around commercial nuclear power,” he said.

While many of the test reactors are small and tout themselves as inherently safer than existing nuclear power plants, they are still capable of leaking radiation in an accident, Lyman noted. “If they are located closer to populated areas, if there aren’t any provisions for offsite radiological emergency planning … then you are potentially putting the public at greater risk, even if the reactors are small,” he said.

Perhaps most worrying, said former NRC Chair Macfarlane, is how the DOE’s safety assessment might be used to build more small reactors across the country, once the pilot reactors are built.

………………………………………..Macfarlane is unconvinced. She said relying on the hasty DOE analysis for the construction of potentially dozens or even hundreds of small reactors around the U.S. is the real risk.

“They can look at what the DOE did, they can take it as a piece of input, but they have to do their own separate analysis,” she warned. “Otherwise, none of us are safe.” https://www.npr.org/2025/12/17/nx-s1-5608371/trump-executive-order-new-nuclear-reactors-safety-concerns

Report: Small Modular Distractors: Why a European SMR strategy hinders the energy transition

09/12/2025, https://caneurope.org/small-modular-distractors/

Click on image [on original] to download the report

“Our investigation demonstrates why betting on small modular reactors would be a costly mistake for Europe. These projects would be slow to construct, with long delays, over budget, a poor economic fit for our power system needs, and would produce toxic radioactive waste for which we do not have a solution. Many projects would likely not materialise and jeopardise our electricity supply. Distorting funding away from more realistic, lower-cost solutions such as renewables, storage, and demand side solutions risks derailing the energy transition, keeping our emissions and energy prices high.” – Thomas Lewis, Author and Energy Policy Coordinator at CAN Europe

An EU Small Modular Strategy is a distraction

Small modular reactors are not a viable solution to decarbonising our energy system and supporting a transition to net zero. The technology has not been demonstrated at any sort of scale, with great unknowns when it comes to design.

CAN Europe’s latest report details how SMR projects have been shown to be significantly delayed compared to initial estimates, are slower to construct than traditional nuclear, consistently over budget, more expensive than renewables, not economically fit to provide flexibility, not very small, deter funding away from realistic renewable solutions, produce more waste than traditional nuclear, and citizens have little trust in their governments to implement plans fairly. They are also planned under the assumption that the governments would take responsibility and invest in enabling infrastructure such as grids and nuclear storage facilities.

An EU SMR Strategy, as well as national plans to pursue SMRs, risks diverting attention, resources, and political momentum away from the proven solutions needed for a fast, fair, and effective energy transition. While the following recommendations aim to minimise the potential negative impacts of SMR-related initiatives, it is important to underline that only a transition pathway without new nuclear capacity can deliver the speed, cost-effectiveness, and system resilience required for Europe’s decarbonisation.

Diagrams and graphs within the report can be downloaded below: [ on original]

The UK wants to unlock a ‘golden age of nuclear’ but faces key challenges in reviving historic lead.

The U.K.’s Nuclear Regulatory Taskforce called for urgent reforms after identifying “systemic failures” in the country’s nuclear framework. It found that fragmented regulation, flawed legislation and weak incentives led the U.K. to fall behind as a nuclear powerhouse.

The government committed to implementing the taskforce’s guidance and is expected to present a plan to do so within three months. There is not, at the moment, a single SMR actively producing electricity under four revenues. They will all come at best in the 30s,” Ludovico Cappelli, portfolio manager of

Listed Infrastructure at Van Lanschot Kempen, told CNBC.

While SMRs are a “game changer” thanks to their ability to power individual factories or small towns, their days of commercial operation are too far away, he said.

From an investment standpoint, “that is still a bit scary,” he added. To secure the large baseloads needed to offset the intermittency of renewables, “we’re still looking at big power stations,” added Paul Jackson, Invesco’s EMEA global market strategist.

CNBC 6th Dec 2025, https://www.cnbc.com/2025/12/06/the-history-of-nuclear-energy-lies-on-british-soil-does-its-future-.html

$400 Million DOE Bailout for “SMRs” at Palisades

Multiple reactors on the tiny 432-acre site also introduce the risk of domino-effect multiple meltdowns

Holtec’s inexperience exacerbates these synergistic old and new reactor risks. Holtec still has no NRC-approved SMR-300 design certification, has never built a reactor, nor operated one, nor repaired and restarted one, let alone a reactor as perpetually problem-plagued as the 60-year old Palisades zombie.

DECEMBER 3, 2025, by Kevin Kamps

regarding the announcement by the U.S. Department of Energy, Holtec International, and Michigan Governor Gretchen Whitmer of a $400 million federal bailout for “Small Modular Reactor” deployments at the Palisades nuclear power plant in Covert Township, Van Buren County, southwest Michigan.

Holtec’s uncertified and untested so-called ‘Small Modular Reactor’ design, the SMR-300, is not small. At 300 megawatts-electric (MW-e) each, the additional 600 MW-e would nearly double the nuclear megawattage at Palisades, given the unprecedented zombie restart of the 800 MW-e, six decade old reactor there. The zombie reactor was designed in the mid-1960s, and ground was broken on construction in 1967, with the learn-as-we-go dangerous design and fabrication flaws at the nuclear lemon baked in, still putting us in peril to the present day.

Just look at the harm smaller infamous 67 MW-e Michigan reactors have caused in the past. At Fermi Unit 1 on the Lake Erie shore in Monroe County, “we almost lost Detroit” when the plutonium breeder reactor had a partial core meltdown on October 5, 1966. John G. Fuller wrote an iconic book about it by that title in 1975. And Gil Scott-Heron wrote a haunting song about it in 1977, two years before he joined Musicians United for Safe Energy (MUSE) in response to the 1979 Three Mile Island Unit 2 meltdown, the worst reactor disaster in U.S. history — thus far anyway.

And at Big Rock Point — Palisades’ sibling reactor — near Charlevoix on the northwest Lower Peninsula’s Lake Michigan shore, the 67 MW-e experimental reactor shockingly released more than 3 million Curies of hazardous ionizing radioactivity into the environment, from supposedly ‘routine operations’ from 1962 to 1997. In the 1970s, local family practitioner, medical doctor Gerald Drake, and University of Michigan trained statistician Martha Drake, documented statistically significant spina bifida in the immediate area downwind. There is also anecdotal evidence of widespread thyroid pathology as well. This is similar to Palisades, where 50 cases of diagnosed thyroid cancer have been alleged by part-time residents of the small, 120-year old Palisades Park Country Club resort community, where there should not be a single such case of this exceedingly rare disease made infamous by Chornobyl and Fukushima.

Given the damage done by 67 MW-e reactors in Michigan in the past, just imagine what havoc could be wreaked by two 300 MW-e reactors — each 4.5 times larger — at Palisades going forward.

Increased breakdown phase risks at the 60-year old zombie reactor, and break-in phase risks at the two SMR-300 new builds, are a recipe for disaster at Palisades.

Palisades has a long list of breakdown phase risks. From the worst neutron-embrittled reactor pressure vessel in the country or perhaps even the entire world, to severely degraded steam generator tubes, a reactor lid that needed replacement two decades ago, lack of fire protection, calcium silicate containment insulation that would dissolve into sludge with the viscosity of Elmer’s Glue blocking emergency core cooling water flow, the worst operating experience in industry with control rod drive mechanism seal leaks from 1972 to 2022, etc., the Palisades zombie reactor has multiple pathways to reactor core meltdown, which would unleash catastrophic amounts of hazardous ionizing radioactivity into the environment, on the beach of Lake Michigan, drinking water supply for 16 million people along its shores, and more than 40 million people downstream and downwind, up the food chain, and down the generations throughout the Great Lakes region.

Chornobyl in Ukraine in 1986, and Three Mile Island-2 in Pennsylvania in 1979, are examples of brand new reactors causing catastrophes. Through design and construction flaws, and operator inexperience, Holtec’s SMR-300s will introduce increased break-in phase risks at the Palisades nuclear power plant, located on the Great Lakes shoreline. The Great Lakes comprise 21% of the planet’s, 84% of North America’s, and 95% of the United States’ surface fresh water.

Multiple reactors on the tiny 432-acre site also introduce the risk of domino-effect multiple meltdowns, as happened at Fukushima Daiichi, Japan in March 2011.

A 1982 U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) study the agency unsuccessfully tried to suppress reported that a Palisades meltdown would cause a thousand acute radiation poisoning deaths, 7,000 radiation injuries, 10,000 latent cancer fatalities, and $52 billion in property damage. Adjusting for inflation alone, property damage would now exceed $168 billion. And since populations have increased around Palisades in the past 43 years, casualty figures would be significantly worse, as more people now live in harm’s way.

Holtec’s inexperience exacerbates these synergistic old and new reactor risks. Holtec still has no NRC-approved SMR-300 design certification, has never built a reactor, nor operated one, nor repaired and restarted one, let alone a reactor as perpetually problem-plagued as the 60-year old Palisades zombie. Holtec’s incompetence and corruption has been on full display in just the past several weeks, including a leak of large amounts of ultra-toxic hydrazine into Lake Michigan, the unprecedented fall by a worker into the radioactive reactor cavity, and evidence of potential alcohol consumption and/or drug impairment, including in the protected area, and by a supervisor. Despite all this, NRC has rubber stamped weakened work hour limitations, meaning overworked employees will be more fatigued, as Holtec races to restart the zombie reactor, in order to hold its announced Initial Public Offering, hoping to raise another $10 billion in private investment, for SMR-300 deployment across the country and around the world, with Palisades as the dangerously dubious prototype to be followed.

Speaking of money, Holtec has, thus far, been awarded $3.52 billion (with a B!) in public funding at Palisades alone. But it has requested another $12 billion (with a B!) more. These bailouts significantly impact the pocketbooks of hard working Americans — state and federal taxpayers, as well as electric ratepayers. Palisades represents a wealth redistribution scheme, from the American people to Holtec, compliments of Governor Whitmer, the Michigan state legislature, Congress, President Biden, and now President Trump. Abe Lincoln described the ideal of government as “of, by, and for the people.” At Palisades, government seems to be of, by, and for an inexperienced, incompetent, careless, corrupt and greed-driven corporation, playing radioactive Russian roulette, carrying out a large-scale nuclear experiment, with Great Lakes residents as the unwitting Guinea pigs.”

Could Small Modular Nuclear Reactors add supply-side grid flexibility?

It would make sense in the UK for SMRs to be load

following only if there were vast numbers of SMRs deployed,

13 Nov, 2025 By Tom Pashby New Civil Engineer

Small modular reactors (SMRs) could have the capability of providing the British electricity grid with flexible supplies, the government has said.

Supply-side grid flexibility is the ability of electricity sources to

adjust their output to match fluctuations in power demand in real-time. The

statement came in response to a question from an MP about whether SMRs

could be used as “load-following energy sources”.

Liberal Democrat spokesperson for energy security and net zero Pippa Heylings MP asked what assessment the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero (DESNZ) “has made of the potential merits of small modular reactors being made as load-following energy sources”.

Responding, DESNZ minister of state

Michael Shanks said: “The next generation of nuclear, including SMRs,

offers new possibilities, including faster deployment, lower capital costs

and greater flexibility. “Whilst nuclear energy has a unique role to play

in delivering stable, low-carbon baseload energy, SMRs may be able to serve the electricity grid more flexibly than traditional nuclear, as well as

unlock a range of additional applications in energy sectors beyond grid

electricity.”

It would only make sense in the UK for SMRs to be load

following if there were vast numbers of SMRs deployed, representing a

significant proportion of the electricity generation capacity on the

national electricity transmission system of Great Britain, for them to be

load-following.

University of Sussex professor of science and technology

policy Andy Stirling told NCE: “This parliamentary answer repeats a

longstanding malaise in UK energy policy. “For far too long,

eccentrically strong official nuclear attachments have been dominated by

reference to claimed ‘new possibilities’, to what nuclear ‘may be

able’ to do, and to an unsubstantiated ‘unique role’. “

Whichever side of these debates one is on, it is clear that what is needed most is what used to be routine – but has been lacking for more than a decade.

“Questions over cost, security or flexibility claims can only be settled

by detailed comparative analysis that includes balanced attention to

non-nuclear strategies as well as nuclear ‘possibilities’. “

When such a picture is looked at in a fair way, current trends are making it

impossible even for formerly nuclear-enthusiastic bodies (like the Royal

Society) to conclude – even when looking at UK Government data –

anything other than that there is no rational need for any nuclear

contribution.”

New Civil Engineer 13th Nov 2025,

https://www.newcivilengineer.com/latest/could-smrs-add-supply-side-grid-flexibility-13-11-2025/

US ‘disappointed’ that Rolls-Royce will build UK’s first small modular reactors.

Guardian, 13 Nov 25

As Keir Starmer announces SMRs to be built in Wales, US ambassador says Britain should choose ‘a different path.

Keir Starmer has announced that the UK’s first small modular nuclear reactors will be built in north Wales – but immediately faced a backlash from Donald Trump’s administration after it pushed for a US manufacturer to be chosen.

Wylfa on the island of Anglesey, or Ynys Môn, will be home to three small modular reactors (SMRs) to be built by British manufacturer Rolls-Royce SMR. The government said it will invest £2.5bn.

SMRs are a new – and untested – technology aiming to produce nuclear power stations in factories to drive down costs and speed up installation. Rolls-Royce plans to build reactors, each capable of generating 470 megawatts of power, mainly in Derby.

The government also said that its Great British Energy – Nuclear (GBE-N) will report on potential sites for further larger reactors. They would follow the 3.2GW reactors under construction by French state-owned EDF at Hinkley Point C in Somerset and Sizewell C in Suffolk.

The Labour government under Starmer has embraced nuclear energy in the hope that it can generate electricity without carbon dioxide emissions, while also providing the opportunity for a large new export industry in SMRs.

However, it faced the prospect of a row with the US, piqued that its ally had overlooked the US’s Westinghouse Electric Company when choosing the manufacturer for the Wylfa reactors.

Ahead of the publication of the UK announcement, US ambassador Warren Stephens published a statement saying Britain should choose “a different path” in Wales.

“We are extremely disappointed by this decision, not least because there are cheaper, faster and already-approved options to provide clean, safe energy at this same location,” he said.

The Trump administration last month signed an $80bn (£61bn) deal with Westinghouse, which had been struggling financially, to build several of the same larger reactors proposed at Wylfa. Under the terms of that deal, the Trump administration could end up taking a stake in the company……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2025/nov/13/us-disappointed-that-rolls-royce-will-build-uks-first-small-modular-reactors

The SMR boom will soon go bust

by Ben Kritz, 3 Nov 25, https://www.msn.com/en-ph/technology/general/the-smr-boom-will-soon-go-bust/ar-AA1PJi1U

ONE sign that the excessively hyped concept of small modular reactors (SMRs) is now living on borrowed time is the lack of enthusiasm in the outlook from energy market analysts, whether they are individuals such as Leonard Hyman, William Tilles and Vaclav Smil, or big firms such as JP Morgan and Jones Lang LaSalle. None of them are optimistic that the sector will be productive before the middle of next decade, and the more critical ones are already predicting that it will never be, and that the “SMR bubble” will burst before the end of this one. My frequent readers will already know that I stand firmly with the latter view; basic market logic, in fact, makes any other view impossible.

In a recent commentary for Oil Price.com, one of the rather large number of online energy market news and analysis outlets, Hyman and Tilles predicted that the SMR bubble will burst in 2029. They based this on the reasonable observation that power supply forecasts are typically done on a three- to five-year timeframe. The fleet of SMRs that are currently expected to be in service between 2030 and 2035 simply will not be there, so energy planners will, at a minimum, omit them from the next planning window, and might decide to forget about them entirely. Deals will dry up, investors will dump their stocks or stop putting venture capital into SMR developers, and those developers will find themselves bankrupt.

That is an entirely plausible and perhaps even likely scenario, but the SMR bubble may burst much sooner than that, perhaps even as soon as next year, because of the existence of the other tech bubble, artificial intelligence, or AI, an acronym that in my mind sounds like “as if.” The topic of the AI bubble is an enormous can of worms, too complex to discuss right now, but the basic problem with it that is relevant to the SMR sector is that AI developers need a great deal of energy immediately. It has reached a point where AI-related data centers are described in terms of their energy requirements — in gigawatt increments — rather than their processing capacity. The availability of power determines whether or not a data center can be built; if the power is not already available, it must be within the relatively short time it will take to complete the data center’s construction.

Even if SMRs were readily available, their costs would discourage customers; AI developers are not too concerned with energy costs now, but they will be as their needs to start actually generating a profit become more acute. On a per-unit basis, SMRs are and are likely to always be more expensive than conventional, gigawatt-scale nuclear plants, and for that matter, most other power supply options. Hyman and Tilles estimate that on a per-unit cost basis (e.g., cost per megawatt-hour or gigawatt-hour), SMRs will be about 30 percent higher than the most efficient available gigawatt-scale large nuclear plants. Being smaller, SMRs would — hypothetically, as they do not actually exist yet — certainly cost less up front than large nuclear or conventionally fueled power plants, but their electricity would cost much more in the long run. That might not be an issue in some applications, but it certainly would if SMRs were intended to supply electricity to a national or regional grid.

Some analyses point out that some early adopters of SMRs, that is, customers who have put down money or otherwise promised to order one or more SMR units if and when they become available, may not be particularly price-sensitive; for example, military customers, governments taking responsibility for supplying electricity to remote areas, or some industrial customers. However, they would still be tripped up by the fragmented nature of the SMR sector, which was caused by the “tech bro” mindset of ignoring almost 70 years of experience in nuclear development and trying to reinvent the wheel.