Energy Security Minister Graham Stuart opposes Holderness nuclear waste site

By Stuart Harratt, BBC News

A MP said he is supporting efforts to oppose plans to bury nuclear waste in East Yorkshire.

Beverley and Holderness Conservative MP Graham Stuart called on East Riding Council to withdraw from discussions with Nuclear Waste Services (NWS).

The government agency has named South Holderness as a potential site for a Geological Disposal Facility (GDF).

Mr Graham, who is also the Minister for Energy Security, had previously called for a public vote on the proposals.

He now says he is supporting a motion by two local Conservative councillors, Lyn Healing and Sean McMaster, asking that the local authority stop talks with NWS.

‘Community says no’

“South Holderness is a special place, and the news that the area was being considered as the site for the UK’s GDF shocked many in our community,” Mr Stuart said.

“It is the people of Holderness who should determine what happens in their area and they have made clear their opposition to these plans.”

He added: “Our community says ‘No’ and Lyn and Sean have my backing to seek our withdrawal.”

Ms Healing and Mr McMaster said their motion to withdraw from discussions would be submitted to a full council meeting on 21 February.

“Yes, investment in Holderness is badly required but is this the right investment? We now believe it isn’t,” the councillors said……………………………………………………………………………… more https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-humber-68233882

Nuclear industry veterans warn some radioactive waste destined for Ontario disposal facility should not be accepted

Observer, Natasha Bulowski • Feb 16, 2024 •

Approval of a nuclear waste disposal site near the Ottawa River hinged on a promise that only low-level radioactive waste would be accepted. But former nuclear industry employees and experts warn some waste slated for disposal contains unacceptably high levels of long-lived radioactive material.

The “near-surface disposal facility” at Chalk River Laboratories (CRL) will store up to one million cubic metres of current and future low-level radioactive waste inside a shallow mound about one kilometre from the river, which provides drinking water to millions of people in the region. But former employees who spent decades working at the labs in waste management and analysis say previous waste-handling practices were inadequate, imprecise and not up to modern standards. Different levels of radioactive material were mixed together, making it unacceptable to bury in the mound.

“Anything pre-2000 is anybody’s guess what the hell they have on their hands,” said Gregory Csullog, a retired waste inventory specialist and former longtime employee of Atomic Energy of Canada Limited (AECL), the Crown corporation that ran the federal government’s nuclear facilities before the Harper government privatized it in 2015.

Csullog described the waste during this earlier time as an unidentifiable “mishmash” of intermediate- and low-level radioactivity because there were inadequate systems to properly label, characterize, store and track what was produced at Chalk River or shipped there from other labs. “Literally, there were no rules,” said Csullog, who was hired in 1982 to develop waste identification and tracking systems.

International safety standards state low-level radioactive waste is suitable for disposal in various facilities, ranging from near the surface to 30 metres underground, depending primarily on how long it remains radioactive. High-level waste, like used fuel rods, must be buried hundreds to thousands of metres underground in stable rock formations and remain there, effectively forever. Intermediate-level waste is somewhere in the middle and should be buried tens to hundreds of metres underground, not in near-surface disposal facilities, according to the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA).

Radioactive waste is recognized by many health authorities as cancer-causing and its longevity makes disposal a thorny issue. Even short-lived radioactive waste typically takes hundreds of years to decay to extremely low levels and some radioactive isotopes like tritium found in the waste — a byproduct of nuclear reactors — are especially hard to remove from water.

Canadian Nuclear Laboratories (CNL) originally wanted its near-surface disposal facility to take intermediate- and low-level waste when it first proposed the project in 2016. Backlash was swift and concerned groups, including Deep River town council and multiple experts, argued it would transgress international standards to put intermediate-level waste in that type of facility. In 2017, CNL changed its proposal and promised to only accept low-level waste. The announcement quelled the Deep River town council’s concern, but some citizen groups, scientists, former employees and many Algonquin Nations aren’t buying it.

CNL says its waste acceptance criteria will ensure all the waste will be low-level and comply with international and Canadian standards. Eighty seven per cent of the waste will be loose soil and debris from environmental remediation and decommissioned buildings. The other 13 per cent “will have sufficiently high radionuclide content to require use of packaging” in containers, drums or steel boxes in the disposal facility, according to CNL.

However, project opponents note that between 2016 and 2019, about 90 per cent of the intermediate-level waste inventory at federal sites was reclassified as low-level, according to data from AECL and a statement from CNL. The timing of the reclassification raised the alarm for critics, who took it to mean intermediate-level waste was inappropriately categorized as low-level so it could be stored in the Chalk River disposal facility. CNL said the 2016 estimate was based on overly “conservative assumptions” and the waste was reclassified after some legacy waste was retrieved, examined and found to be low-level.

The disposal facility will also accept waste generated over the next two decades and some shipments from hospitals and universities.

The history of Chalk River Laboratories

To fully understand the nuclear waste problem, you first have to know the history of Chalk River Lab’s operations and accidents,…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… more https://www.pembrokeobserver.com/news/local-news/nuclear-industry-veterans-warn-some-radioactive-waste-destined-for-ontario-disposal-facility-should-not-be-accepted Natasha Bulowski is a Local Journalism Initiative reporter working out of Canada’s National Observer. LJI is funded by the Government of Canada.

Holtec International avoids criminal prosecution related to false documents, pays $5m fine.

Holtec International avoids criminal prosecution related to false documents

NJ Spotlight News, JEFF PILLETS | JANUARY 30, 2024

Holtec International, the Camden firm behind controversial nuclear power projects in New Jersey and four other states, has agreed to pay a $5 million penalty to avoid criminal prosecution connected to a state tax break scheme.

New Jersey Attorney General Matthew J. Platkin announced Tuesday that Holtec has been stripped of $1 million awarded by the state in 2018 under the Angel Investor Tax Break Program. Holtec will also submit to independent monitoring by the state for three years regarding any application for further state benefits, Platkin said.

The agreement, which also covers a real estate company owned by Holtec founder and CEO Krishna Singh, came after a lengthy criminal investigation that discovered Holtec had submitted false information to the state in seeking the Angel tax breaks.

Holtec’s use of misinformation for private gain, as detailed by the state attorney general, closely parallels allegations that have followed the company for years as it sought public subsidies to finance international ambitions in the nuclear field……………………………………..

Previously fined

In 2010, the Tennessee Valley Authority fined Holtec $2 million and ordered company executives to take ethics training after a bribery investigation involving Singh’s dealings with a key subcontractor.

The TVA also banned Holtec from federal work for 60 days, the first ever such debarment in the agency’s history.

In 2023, Holtec’s former chief financial officer filed a federal lawsuit claiming that he had been fired after refusing to sign off on false financial information the company was allegedly sending to potential investors. Kevin O’Rourke alleges that Holtec intentionally sought to inflate revenue projections and hide millions in expected losses.

Those allegations, which Holtec has denied, include the company’s effort to mask $750 million in potential losses for its controversial proposal to build a consolidated nuclear waste storage facility in southeast New Mexico. That project, which was approved by federal regulators last year, faces a federal court challenge lodged by private groups and New Mexico state officials, who say Holtec lied about key information on its applications to build the storage facility.

The alleged false information, New Mexico officials say, included Holtec’s representation that it had obtained property rights from mine owners and oil drillers who are active near the 1,000-acre plot of desert land where Holtec would eventually place up to 10,000 spent nuclear fuel canisters with some 120,000 metric tons of radioactive waste.

New Mexico lawsuit

New Mexico Land Commissioner Stephanie Garcia Richard, who is suing in federal court to stop the Holtec plan, told NJ Spotlight News in an earlier interview that Holtec’s “false claims” could have profound potential impact on her state. There are more than 50 oil, gas and mineral wells within a 10-mile radius of Holtec’s site, she said, and the potential for underground contamination is real.

“I understand we need to find a [nuclear waste] storage solution, but not in the middle of an active oil field, not from a company that is misrepresenting facts,” Garcia Richard said in an earlier statement.

New Mexico state Sen. Jeff Steinborn, whose law to ban the facility is now part of that federal lawsuit, told NJ Spotlight News that questions about Holtec’s character should be a deep concern for the public. Holtec, he pointed out, plans to transport dangerous spent fuel from retired power reactors across the nation to the site……………………………………………………………….

Decommissioning operations

Over the past half-decade, Holtec has moved aggressively forward from its manufacturing roots to take ownership of closed nuclear plants that are in the process of being retired. The company runs decommissioning operations at the retired Oyster Creek generating station along Barnegat Bay at Lacey Township, and three other sites, including New York’s Indian Point and the Pilgrim plant in Massachusetts.

The company has informally discussed starting up some of the new reactors at Oyster Creek and the Palisades site in Michigan, and is also pursuing plans to bring the next-gen nukes to Ukraine, Great Britain and other countries overseas.

Holtec now controls billions in public money that was set aside by utility users in each state for the safe decommissioning of nuclear reactors, a process that regulators have estimated could take 60 years for most reactors. Holtec, instead, has claimed it could dismantle the old plants and restore the land for public use in a fraction of that time.

Despite approval from the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, public interest groups worry that Holtec, a private limited liability company, may drain the decommissioning trust funds and go bankrupt in its effort to complete expedited closure of some of America’s oldest nuclear plants.

Legal settlements elsewhere

Attorneys general in Massachusetts and New York were so worried that taxpayers could be left high and dry, they filed lawsuit pointing out multiple inconsistencies in Holtec’s plans. Both states have won legal settlements designed to stop Holtec from depleting the trust funds.

In addition to controlling the public trust funds, Holtec has also received or applied for billions in taxpayer subsidies and federal grants and loans. Some of those subsidies would help the firm finance its proposed storage dump in the New Mexico desert, as well as construction of a new generation of so-called SMRs, or small modular reactors.

The company has informally discussed starting up some of the new reactors at Oyster Creek and the Palisades site in Michigan, and is also pursuing plans to bring the next-gen nukes to Ukraine, Great Britain and other countries overseas.No such small nuclear reactor has ever been brought online in the U.S., as they face significant costs and regulatory hurdles despite the support of some policymakers who argue that nuclear power can help reduce atmospheric carbon. A plan to build SMRs in Idaho collapsed last year after its cost more than doubled, to $9 billion.

It is unclear how the fine and criminal investigation announced Tuesday by New Jersey might affect Holtec’s plans to develop a new fleet of reactors.

The NJ case

According to the attorney general’s office, Holtec’s false tax break application concerned its partnership with a battery manufacturing firm named Eos Energy Storage. Holtec had planned on using Eos to help develop SMR technology at a manufacturing plant in western Pennsylvania.

Holtec and Singh Real Estate, a subsidiary owned by the company’s owner, invested $12 million in Eos in exchange for six million shares in the company. Holtec, however, manipulated its tax break application to hide information about the investment and double its tax award from $500,000 to $1 million, according to the attorney general

Investors in EOS have brought a class-action lawsuit against the battery manufacturer, citing unspecified financial fraud. Securities and Exchange Commission documents filed by the firm show Singh was briefly a member of the company’s board of directors before resigning………………………

State courts ruled in favor of Holtec after finding that the state regulators who administer the tax break program failed to perform adequate due diligence on applicants with spotty ethical backgrounds.

Public interest groups and nuclear safety experts who continue to oppose Holtec’s plans around the country, however, say the New Jersey fine is another warning sign. They said federal regulators, including the Department of Energy, must redouble scrutiny before awarding more public subsidies to the company.

“Clearly, Holtec lies habitually for fraudulent financial gain,” said Kevin Kamps, a radioactive waste specialist at Beyond Nuclear, a leading watchdog group that is suing to stop Holtec’s New Mexico plan, as well as efforts to collect billions in subsidies to restart the retired Palisades nuclear plant in Michigan.

“The State of Michigan, and U.S. Department of Energy, must… not hand over hundreds of millions of dollars in state, and multiple billions of dollars in federal, taxpayer money for Holtec’s unprecedented, extremely high-risk zombie reactor restart scheme at Palisades.” https://www.njspotlightnews.org/2024/01/holtec-camden-will-pay-5-million-fine-false-documents-nj-tax-breaks-controversial-nuclear-projects/

Radioactive waste beside Ottawa River will remain hazardous for thousands of years: Citizens’ groups

Toula Mazloum, CTV News Ottawa Digital Multi-Skilled Journalist, Feb. 5, 2024

Citizens’ groups from Ontario and Quebec have issued a warning saying that the radioactive waste destined for a planned nuclear waste disposal facility in Deep River, Ont., one kilometre from the Ottawa River, will remain hazardous for thousands of years.

The disposal project — a seven-storey radioactive mound known as the “Near Surface Disposal Facility” (NSDF) – was licensed by the Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission (CNSC) last month.

The CNSC said it determined the project is not likely to cause significant adverse effect, “provided that [Canadian Nuclear Laboratories] implements all proposed mitigation and follow-up monitoring measures, including continued engagement with Indigenous Nations and communities and environmental monitoring to verify the predictions of the environmental assessment.”

The groups sent a letter Sunday to the federal government, asking to stop all funding for the project and to look for alternate ways to dump the waste underground.

In the letter, the groups warned that waste destined for the mound is “heavily contaminated with very long-lived radioactive materials” that puts the public at risk of developing cancer, birth defects and genetic mutations.

“We believe Cabinet or Parliament has the power to reverse this decision and they need to do so as soon as possible,” said Lynn Jones of Concerned Citizens of Renfrew County and Area.

“It’s clear that the only benefit from the NSDF would go to shareholders of the three multinational corporations involved, AtkinsRéalis (formerly SNC-Lavalin), Fluor and Jacobs. Everyone else would get only harm—a polluted Ottawa River, plummeting property values, increased health risks, never-ending costs to remediate the mess and a big black mark on Canada’s international reputation.”

One million tons of radioactive and other hazardous waste from eight decades of operations of the Chalk River Laboratories (CRL) will be held if the project is completed, according to the group.

The groups say that according to scientists and after a few hundred years, “the mound would leak during operation and break down due to erosion,” contaminating drinking water in the Ottawa River.

The controversial project has been concerning for many residents and organizations since 2016, including residents of Renfrew County and Area, the Old Fort William (Quebec) Cottagers’ Association, Ralliement contre la pollution radioactive and the Canadian Coalition for Nuclear Responsibility, the groups say.

“People need to wake up and realize the truth that this waste is full of deadly long-lived, man-made radioactive poisons such as plutonium that will be hazardous for many thousands of years,” said Johanna Echlin of the Old Fort William (Quebec) Cottagers’ Association.

Waste from CRL is classified as an “Intermediate-level” waste class, which means it must be kept tens of metres underground, says the International Atomic Energy Agency

“A former senior manager in charge of ‘legacy’ radioactive waste at Chalk River told the Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission that, in reality, the waste proposed for emplacement in the NSDF is ‘intermediate level waste’ that requires a greater degree of containment and isolation than that provided by a near surface facility.’ He pointed out the mound would be hazardous and radioactive for many thousands of years, and that radiation doses from the facility will, in the future, exceed regulatory limits,” the groups noted.

Citizens’ groups want Canada to commit to building world class facilities not only for managing radioactive waste that would keep Canadians safe, but also for safely managing the waste for generations to come.

CTV News has reached out to Canadian Nuclear Laboratories (CNL) for comments.

In a statement to CTV News Ottawa, the CNSC said it will ensure that CNL meets all legal and regulatory requirements as well as licence conditions, through regular inspections and evaluations.

“The purpose of the NSDF Project is to provide a permanent disposal solution for up to 1 million cubic metres of solid low-level radioactive waste, such as contaminated personal protective clothing and building materials,” the statement said. “The majority of the waste to be placed in the NSDF is currently in storage at the Chalk River Laboratories site or will be generated from environmental remediation, decommissioning, and operational activities at the Chalk River Laboratories site. Approximately 10% of the waste volume will come from other AECL-owned sites or from commercial sources such as Canadian hospitals and universities.”

CNSC says its Jan. 10 decision applies to the construction of the NSDF project only.

“Authorization to operate the NSDF would be subject to a future Commission licensing hearing and decision, should CNL come forward with a licence application to do so. No waste may be placed in the NSDF during the construction phase of the project,” the regulator said.

The site for the NSDF is on the CRL property, 180 km northwest of Canada’s capital, on the Ottawa River directly across from the Province of Quebec.

Nuclear secret: India’s space program uses plutonium pellets to power missions

Rt.com 5 Feb 24

New Delhi is experimenting with radioisotopes to charge its robotic missions to the Moon, Mars and beyond.

Indians are ecstatic over their space program’s string of successes in recent months. The Indian Space Research Organization (ISRO) has a couple of well-kept tech secrets – one of them nuclear – that will drive future voyages to the cosmos.

In the Hollywood sci-fi movie ‘The Martian’, astronaut Mark Watney, played by Matt Damon, is presumed dead and finds ways to stay alive on the red planet, mainly thanks to a big box of Plutonium known as a Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generator (RTG).

In the film, Watney uses it to travel in his rover to the ‘Pathfinder’, a robotic spacecraft which launched decades ago, to use its antenna to communicate with his NASA colleagues and tell them he’s still alive. Additionally, the astronaut dips this box into a container of water to thaw it.

In real life, the RTG generates electricity from the heat of a decaying radioactive substance, in this case, Plutonium-238. This unique material emits steady heat due to its natural radioactive decay. Its continuous radiation of heat, often lasting decades, made it the material of choice for producing electrical power onboard several deep-space missions of the erstwhile USSR and the US.

For short-duration voyages, Soviet missions used other isotopes, such as a Polonium-210 heat source in the Lunokhod lunar rovers, two of which landed on the Moon, in 1970 and 1973.

NASA has employed Plutonium-238 to produce electricity for a wide variety of spacecraft and hardware, from the science experiments deployed on the Moon by the Apollo astronauts to durable robotic explorers, such as the Curiosity Mars rover and the Voyager 1 and 2 spacecraft, which are now at the edge of the solar system.

The ISRO first used nuclear fuel to keep the instruments and sensors going amid frigid conditions during a successful lunar mission, Chandrayaan-3. A pellet or two of Plutonium-238 inside a scaled-down version of the RTG known as the radioisotope heating unit (RHU) made its way to space aboard the rocket. It was provided by India’s atomic energy experts.

RHUs are similar to RTGs but smaller. They weigh 40 grams and provide about one watt of heat each. Their ability to do so is derived from the decay of a few grams of Plutonium-238. However, other radioactive isotopes could be used by today’s space explorers……………………………………………………………………………………..

Meanwhile, the Indian space agency has also kept under wraps two critical technologies developed for future missions by a Bengaluru-based space tech startup, Bellatrix Aerospace.

These unique propulsion systems – engines that utilize electricity instead of conventional chemical propellants onboard satellites – were tested in space aboard POEM-3 (PSLV Orbital Experimental Module-3), which was launched by PSLV on January 1, 2024. The crew also tried replacing hazardous Hydrazine with a non-toxic and environment-friendly, high-performing proprietary propellant.

Hydrazine, an inorganic compound that is used as a long-term storable propellant has been used in the past by various space agencies; even for thrusters on board NASA’s space shuttles. However, it poses a host of health hazards; engineers wear space suits to protect themselves while loading it before the launch of a satellite or a deep-space probe.

In 2017, the European Union recommended banning its use as a satellite fuel, prompting the European Space Agency (ESA) to research alternatives to Hydrazine. The US administration has proposed a ban on the use of Hydrazine to propel satellites in outer space by 2025……… https://www.rt.com/india/591138-india-space-program-plutonium-pellets/

MP calls for vote on Holderness nuclear site which local petition brands ‘hazardous waste dumping ground’

Graham Stuart has called for a public vote on whether a nuclear waste site

should be built in Holderness amid opposition from some living in the area.

‘Beverley and Holderness ‘ MP said Nuclear Waste Services, the Government

Agency which unveiled the waste site proposals last week, should be forced

to make their case directly to the public. Joanne Turner, whose Change.org

petition calls for the site to be rejected, said the beautiful south

Holderness area should not be turned into a dumping ground for hazardous

waste.

Hull Daily Mail 31st Jan 2024

2

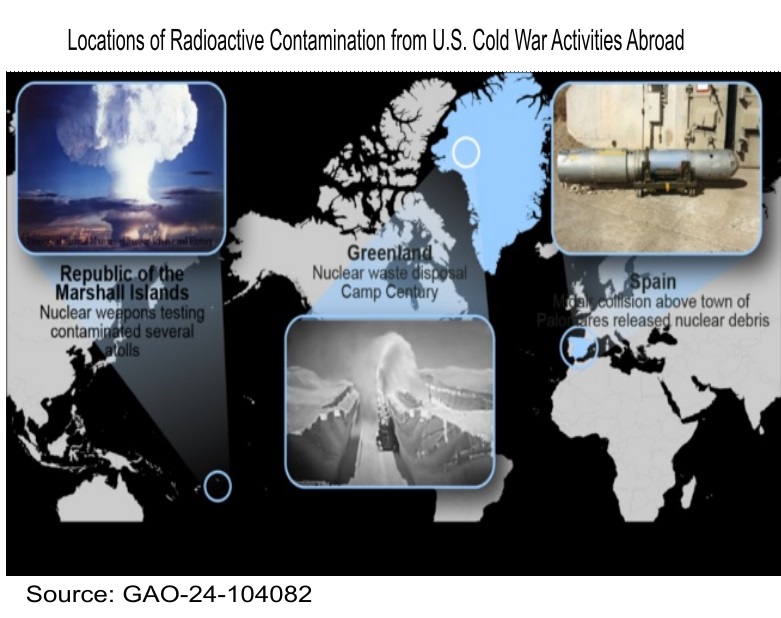

Nuclear Waste: Changing Conditions May Affect Future Management of Contamination Deposited Abroad During U.S. Cold War Activities

GAO-24-104082 U.S. Government Accountability Office Jan 31, 2024.

U.S. Cold War activities caused radioactive contamination in three other countries.

The contamination in Greenland—from a closed nuclear reactor—and in Spain—from an aircraft accident—is being monitored. But changing climate and economic conditions have raised concerns about future effects on local areas.

In the Marshall Islands—where the U.S. tested nuclear weapons—local officials are worried that rising sea levels may impact contaminated sites. The Department of Energy believes the health risk is low but has struggled to explain this to the community. We recommended DOE develop a communication strategy on the contamination for the islands.

The U.S. built Runit Dome in the 1970s to contain radioactive debris in the Marshall Islands.

Highlights

What GAO Found

U.S. Cold War activities resulted in radioactive contamination in three locations: Greenland (part of the Kingdom of Denmark), Spain, and the Republic of the Marshall Islands (RMI) (see fig.). In Greenland, radioactive liquid—generated by a small nuclear reactor that powered the U.S. Camp Century base—remains entombed under ice. In Spain, a mid-air collision resulted in radioactive contamination around Palomares. The United States and Spain cleaned up much of the radioactive material and have monitored the remaining material since. In RMI, contamination from nuclear weapons tests and the resulting fallout remains measurable on several atolls, some of which are still uninhabitable.

Conditions have changed in all three locations since the original contamination. Most affected are the environment and inhabitants of RMI, where the Department of Energy (DOE) has ongoing responsibilities. Specifically:

- Greenland. At Camp Century, Denmark instituted permanent ice sheet monitoring to address concerns that climate change could release contamination. However, a 2021 study reported that contamination likely would remain immobile through 2100.

- Spain. In Palomares, Spanish officials reevaluated the radioactive contamination in the 1990s and found it exceeded European Union standards. In 2015, U.S. and Spanish authorities signed a statement of intent to further remediate Palomares but have not reached a final agreement.

- RMI. In RMI, people are concerned that climate change could mobilize radiological contamination, posing risks to fresh water and food sources. DOE assesses human radiation exposure and monitors environmental contamination in RMI. DOE considers human health risk to be low, but RMI officials believe DOE has downplayed the risk. This and other disagreements fuel distrust of DOE’s information. By implementing a sustainable communication strategy in RMI, DOE could improve the Marshallese people’s access to, and trust in, information on contamination as environmental conditions change.

Why GAO Did This Study

The United States conducted defense activities in many countries during the Cold War. These activities resulted in radioactive contamination in three countries: Greenland, Spain, and RMI. During the 1960s, the United States buried radioactive liquid in Greenland’s ice while operating the experimental Camp Century base to study the feasibility of installing nuclear missiles there. In 1966, in Spain, two U.S. defense aircraft collided, dispersing radioactive debris over the town of Palomares. From 1946 to 1958, the United States conducted 67 nuclear weapons tests in RMI, and the resulting radioactive fallout contaminated several atolls.

This report examines (1) the amount and type of radioactive contamination in Greenland, Spain, and RMI; and (2) how conditions have changed at these sites, and the extent to which the environment and inhabitants have been affected by these changed conditions. GAO reviewed key literature on the contamination and interviewed U.S. and foreign government officials.

Recommendations

The Secretary of Energy, as a part of the agency’s ongoing efforts to address the legacy of U.S. nuclear testing in RMI, should develop and document a strategy for communications on radioactive contamination that is sustained, understandable, transparent, engages the RMI government, and builds on lessons learned. DOE concurred with GAO’s recommendation.

Recommendations for Executive Action

Agency Affected RecommendationStatus Department of Energy

The Secretary of Energy, as a part of the agency’s ongoing efforts to address the legacy of U.S. nuclear testing in the Republic of the Marshall Islands, should develop and document a strategy for communications on radioactive contamination that is sustained, understandable, and transparent; engages the RMI government; and builds on lessons learned. (Recommendation 1)

When we confirm what actions the agency has taken in response to this recommendation, we will provide updated information.

Full Report…………………………………………………………….. https://www.gao.gov/products/gao-24-104082

Australia’s State governments fight each other to avoid having to store nuclear wastes

Expect weapons-grade NIMBYism as leaders fight over where to store AUKUS nuclear waste

Given that proposals for even low-level nuclear waste sites have been rejected by communities, who is going to take on the radioactive waste created by our new military pact?

ANTON NILSSON, FEB 01, 2024, Crikey,

here should Australia store the waste created by its investment in nuclear-driven submarines? It’s a question no-one knows the answer to yet — although we do know a couple of places where the radioactive waste won’t be stored. As the search for a solution continues, expect politicians to try to kick the radioactive can further down the road — and expect some weapons-grade NIMBYism from state and territory leaders if they’re asked to help out.

In August last year, plans to build a new nuclear waste storage facility in Kimba in South Australia were scrapped. As Griffith University emeritus professor and nuclear expert Ian Lowe put it in a Conversation piece, “the plan was doomed from the start” — because the government didn’t do adequate community consultation before deciding on the spot.

Resources Minister Madeleine King acknowledged as much when she told Parliament the government wouldn’t challenge a court decision that sided with traditional owners in Kimba, who opposed the dump: “We have said all along that a National Radioactive Waste Facility requires broad community support … which includes the whole community, including the traditional owners of the land. This is not the case at Kimba.”

Kimba wasn’t even supposed to store the high-level waste that will be created by AUKUS submarines — it was meant to store low-level and intermediate-level waste, the kind generated from nuclear medicine, scientific research, and industrial technologies. As King told Parliament, Australia already has enough low-level waste to fill five Olympic swimming pools, and enough intermediate-level waste for two more pools.

Where the waste from AUKUS will go is a question without answer. Deputy Prime Minister Richard Marles said in March last year the first reactor from a nuclear-powered submarine won’t have to be disposed of until the 2050s. He added the government will set out its process for finding dump sites within a year — which means Marles has until March this year to spill the details.

“The final storage site of high-level waste resulting from AUKUS remains a mystery,” ANU environmental historian Jessica Urwin told Crikey. “Considering the historical controversies wrought by low- and intermediate-level waste disposal in Australia over many decades, it is hard to see how any Australian government, current or future, will get a high-level waste disposal facility off the ground.”

In his comments last year, Marles gave a hint as to the government’s intentions: he said it would search for sites “on the current or future Defence estate”.

One such Defence estate site that’s been the focus of some speculation is Woomera in South Australia. “A federal government decision to scrap plans for a nuclear waste dump outside the South Australian town of Kimba has increased speculation it will instead build a bigger facility on Defence land at Woomera that could also accommodate high-level waste from the AUKUS submarines,” the Australian Financial Review reported last year.

Urwin said such a proposal could trigger local opposition as well.

Due to Woomera’s proximity to the former Maralinga and Emu Field nuclear testing sites, and therefore its connections to some of the darkest episodes in Australia’s nuclear history, communities impacted by the tests and other nuclear impositions (such as uranium mining) have historically pushed back against the siting of nuclear waste at Woomera,” she said.

Australian Submarine Agency documents released under freedom of information laws in December last year show there is little appetite among state leaders to help solve the conundrum.

A briefing note to Defence secretary Greg Moriarty informed him that “state premiers (Victoria, Western Australia, Queensland, and South Australia) [have sought] to distance their states from being considered as potential locations”. ………………………………………………….. more https://www.crikey.com.au/2024/02/01/aukus-nuclear-waste-storage-australia/

Still no end in sight for Fukushima nuke plant decommissioning work

January 27, 2024 (Mainichi Japan), https://mainichi.jp/english/articles/20240127/p2a/00m/0na/003000c

OKUMA, Fukushima — Nearly 13 years since the triple-meltdown following the March 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake and tsunami, it is still unclear when decommissioning of the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Station’s reactors will be completed.

Operator Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO) Holdings Inc. showed the power plant to Mainichi Shimbun reporters on Jan. 26 ahead of the 13th anniversary of the nuclear accident. Radiation levels in many areas are almost normal, and people can move in ordinary work clothes. However, the most difficult part of the work, retrieving melted nuclear fuel, has been a challenge. The management of solid waste, which is increasing daily, also remains an issue. The decommissioning of the reactors, which is estimated to take up to 40 years, is still far from complete.

Meltdowns occurred in reactor Nos. 1, 2 and 3. The start of nuclear fuel debris removal at reactor No. 2, which had been scheduled to begin by the end of fiscal 2023, has just been postponed for the third time. Reactor buildings are still inaccessible due to high radiation, meaning the work has to be done remotely.

More than 1,000 tanks for storing treated wastewater are lined up next to reactor Nos. 1 through 4, and new facilities to stably store and process approximately 520,000 cubic meters of existing solid waste are being built by reactor Nos. 5 and 6.

Treated wastewater began being discharged into the ocean in 2023, and the tanks are gradually being removed, but there is no timetable for the disposal of the solid waste. A TEPCO representative said, “The final issue that remains is how to deal with the radioactive waste that continues to be produced even as the decommissioning of the plant progresses.”

Japanese original by Yui Takahashi, Lifestyle, Science & Environment News Department)

MP wants public vote on nuclear waste disposal

Richard Madden, BBC News, 26 January 2024 more https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/crg7nlwnz59o

People in part of East Yorkshire should be given a referendum on a proposal to bury nuclear waste, the area’s MP has said.

Nuclear Waste Services (NWS), a government agency, has identified South Holderness as having potential for a Geological Disposal Facility (GDF).

Beverley and Holderness MP Graham Stuart said any development would need public consent.

Officials behind the scheme said on Thursday that if the community did not express support the disposal facility would not be built.

‘Toughest test’

Mr Stuart said: “Everyone is right to be concerned about the possibility of a nuclear waste facility in our area.

“They are required to get local consent and I want that to be the toughest available test, a referendum of residents in the affected area”, he said.

A working group has been formed to look at the proposal and a series of public meetings will take place.

Drop-in sessions

- 1 February – Patrington Village Hall

- 2 February – Withernsea, The Shores Centre

- 8 February – Aldbrough Village Hall

- 9 February – Easington Community Hall

- 12 February – Burstwick Village Hall

All sessions run from 11:30 – 18:00 GMT.

Officials from NWS said the project could create thousands of jobs and investment in local infrastructure in South Holderness.

But campaigners in other areas have raised concerns about the impact on tourism, house prices and the environment, leading to protests.

The GDF would see waste stored under up to 3,280ft (1000m) underground until its radioactivity had naturally decayed.

Other proposals have been put forward in Cumbria and at Theddlethorpe on the Lincolnshire coast.

Plan to store nuclear waste under Holderness for 175 years

Nuclear waste from across the UK could be stored below an area of East Yorkshire for up to 175 years.

Government agency Nuclear Waste Services (NWS) announced proposals today to build a storage facility beneath South Holderness.

A group has been set up to examine the proposals, but the agency’s chief executive Corhyn Parr said the scheme would only go ahead with residents’ approval.

She said: “This is a consent-based process, meaning if the community does not express support… it won’t be built there.”

Ms Parr added that the new geological disposal facility would bring benefits to the area, including thousands of jobs and transport improvements.

Two similar working groups are already established in Cumbria and at Theddlethorpe on the Lincolnshire coast.

Dr David Richards, independent chair of the South Holderness working group, said the aim was to work with local communities to discuss the potential of a series of vaults and tunnels being built deep underground, or under the sea, where the material would be buried.

He added: “My role as chair is to make sure local communities have access to information and to understand what people think.”…………………………

Graham Stuart, the MP for Beverley and Holderness, said that he will be meeting with Dr David Richards to discuss the plans.

He wrote on Facebook: “I’ll be asking for a copper bottomed guarantee that nothing would happen without public consent…………………………. https://www.itv.com/news/calendar/2024-01-25/plan-to-store-nuclear-waste-under-east-yorkshire-for-175-years

Japan’s Fukushima nuclear plant: further delays for removal of melted fuel debris

About 880 tons of highly radioactive melted nuclear fuel remain inside the three damaged reactors. Critics say the 30- to 40-year cleanup target set by the government and TEPCO for Fukushima Daiichi is overly optimistic. The damage in each reactor is different and plans need to be formed to accommodate their conditions.

NewsDay, By The Associated Press, January 25, 2024

TOKYO — The operator of the tsunami-hit nuclear plant in Fukushima announced Thursday a delay of several more months before launching a test to remove melted fuel debris from inside one of the reactors, citing problems clearing the way for a robotic arm.

The debris cleanup initially was supposed to be started by 2021, but it has been plagued with delays, underscoring the difficulty of recovering from the plant’s meltdown after a magnitude 9.0 quake and tsunami in March 2011.

The disasters destroyed the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant’s power supply and cooling systems, causing three reactors to melt down, and massive amounts of fatally radioactive melted nuclear fuel remain inside to this day.

The government and the Tokyo Electric Power Company Holdings, or TEPCO, initially committed to start removing the melted fuel from inside one of the three damaged reactors within 10 years of the disaster.

In 2019, the government and TEPCO decided to start removing melted fuel debris by the end of 2021 from the No. 2 reactor after a remote-controlled robot successfully clipped and lifted a granule of melted fuel during an internal probe.

But the coronavirus pandemic delayed development of the robotic arm, and the plan was pushed to 2022. Then, glitches with the arm repeatedly have delayed the project since then.

On Thursday, TEPCO officials pushed back the planned start from March to October of this year.

TEPCO officials said that the inside of a planned entryway for the robotic arm is filled with deposits believed to be melted equipment, cables and other debris from the meltdown, and their harder-than-expected removal has delayed the plan.

TEPCO now is considering using a slimmer, telescope-shaped kind of robot to start the debris removal.

About 880 tons of highly radioactive melted nuclear fuel remain inside the three damaged reactors. Critics say the 30- to 40-year cleanup target set by the government and TEPCO for Fukushima Daiichi is overly optimistic. The damage in each reactor is different and plans need to be formed to accommodate their conditions.

TEPCO has previously tried sending robots inside each of the three reactors but got hindered by debris, high radiation and inability to navigate them through the rubble, though they were able to gather some data in recent years.

Getting more details about the melted fuel debris from inside the reactors is crucial for their decommissioning. TEPCO plans to deploy four mini drones and a snake-shaped remote-controlled robot into the No. 1 reactor’s primary containment vessel in February to capture images from the areas where robots have not reached previously……… more https://www.newsday.com/news/nation/Japan-Fukushima-nuclear-plant-melted-fuel-decommissioning-v83291

Japan’s Fukushima nuclear plant further delays removal of melted fuel debris

Daily Mail, 26 Jan 24, TOKYO (AP) – The operator of the tsunami-hit nuclear plant in Fukushima announced Thursday a delay of several more months before launching a test to remove melted fuel debris from inside one of the reactors, citing problems clearing the way for a robotic arm.

The debris cleanup initially was supposed to be started by 2021, but it has been plagued with delays, underscoring the difficulty of recovering from the plant’s meltdown after a magnitude 9.0 quake and tsunami in March 2011……………………………………………

About 880 tons of highly radioactive melted nuclear fuel remain inside the three damaged reactors. Critics say the 30- to 40-year cleanup target set by the government and TEPCO for Fukushima Daiichi is overly optimistic. The damage in each reactor is different and plans need to be formed to accommodate their conditions.

TEPCO has previously tried sending robots inside each of the three reactors but got hindered by debris, high radiation and inability to navigate them through the rubble, though they were able to gather some data in recent years.

Getting more details about the melted fuel debris from inside the reactors is crucial for their decommissioning. TEPCO plans to deploy four mini drones and a snake-shaped remote-controlled robot into the No. 1 reactor’s primary containment vessel in February to capture images from the areas where robots have not reached previously………………. https://www.dailymail.co.uk/wires/ap/article-13006423/Japans-Fukushima-nuclear-plant-delays-removal-melted-fuel-debris.html

NNSA Issues Final Surplus Plutonium Environmental Impact Statement

The Department of Energy’s National Nuclear Security Administration (NNSA) published a Notice of Availability (NOA) in the Federal Register on Jan. 19, 2024, announcing the availability of the final Surplus Plutonium Disposition Program (SPDP) Environmental Impact Statement (EIS). The SPDP would employ the dilute and dispose strategy to safely and securely dispose of up to 34 metric tons of plutonium surplus to the Nation’s defense needs, using new, modified, or existing facilities at sites across the Nation.

The EIS satisfies NNSA’s obligations under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) as the agency seeks to fulfill two important goals:

- Reduce the threat of nuclear weapons proliferation worldwide by dispositioning surplus plutonium in the United States in a safe and secure manner.

- Meet NNSA’s domestic and international legal obligations.

The 34 metric tons of surplus plutonium covered in the EIS was previously intended for use in fabricating mixed oxide (MOX) fuel. After irradiation in commercial power reactors, the fuel would have been stored pending disposal in a deep geologic repository for spent nuclear fuel. DOE cancelled the MOX project in 2018.

NNSA’s preferred alternative, the dilute and dispose strategy, also known as “plutonium downblending,” includes converting pit and non-pit plutonium to oxide, blending the oxidized plutonium with an adulterant, compressing it, encasing it in two containers, then overpacking and disposing of the resulting contact-handled transuranic (CH-TRU) waste underground in the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant (WIPP) facility in New Mexico. The approach would require new, modified, or existing capabilities at the Savannah River Site (SRS) in South Carolina, Los Alamos National Laboratory (LANL) in New Mexico, the Pantex Plant in Texas, and WIPP.

Under the No Action Alternative, up to 7.1 metric tons of non-pit plutonium would be processed at either LANL or SRS. If the processing occurs at LANL, then the resulting plutonium oxide would be transported to SRS. If it occurs at SRS, then the resulting material would remain there. In both cases the processed material would be diluted, characterized, packaged, and transported as CH-TRU defense waste to the WIPP facility for disposal.

The final SPDP EIS is posted on the NNSA NEPA reading room web page. NNSA will publish a Record of Decision (ROD) for the program after Feb. 20, 2024. The ROD will be published in the Federal Register and posted on the DOE NEPA and NNSA NEPA Reading Room websites.

NNSA announced its intent on Dec. 16, 2020, to prepare an EIS to evaluate the environmental impacts of the dilute and dispose strategy. It released the draft EIS for public comment on Dec. 16, 2022. It conducted three in-person public hearings and one virtual public hearing in January 2023. NNSA has incorporated public comments and developed the final SPDP EIS and is committed to complying with all appropriate and applicable environmental and regulatory requirements.

Nuclear power: molten salt reactors and sodium-cooled fast reactors make the radioactive waste problem WORSE

reactors https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00963402.2018.1507791, Lindsay Krall &Allison Macfarlane, 31 Aug 18

reactors https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/00963402.2018.1507791, Lindsay Krall &Allison Macfarlane, 31 Aug 18ABSTRACT

Nuclear energy-producing nations are almost universally experiencing delays in the commissioning of the geologic repositories needed for the long-term isolation of spent fuel and other high-level wastes from the human environment. Despite these problems, expert panels have repeatedly determined that geologic disposal is necessary, regardless of whether advanced reactors to support a “closed” nuclear fuel cycle become available. Still, advanced reactor developers are receiving substantial funding on the pretense that extraordinary waste management benefits can be reaped through adoption of these technologies.

Here, the authors describe why molten salt reactors and sodium-cooled fast reactors – due to the unusual chemical compositions of their fuels – will actually exacerbate spent fuel storage and disposal issues. Before these reactors are licensed, policymakers must determine the implications of metal- and salt-based fuels vis a vis the Nuclear Waste Policy Act and the Continued Storage Rule.

-

Archives

- March 2026 (139)

- February 2026 (268)

- January 2026 (308)

- December 2025 (358)

- November 2025 (359)

- October 2025 (376)

- September 2025 (258)

- August 2025 (319)

- July 2025 (230)

- June 2025 (348)

- May 2025 (261)

- April 2025 (305)

-

Categories

- 1

- 1 NUCLEAR ISSUES

- business and costs

- climate change

- culture and arts

- ENERGY

- environment

- health

- history

- indigenous issues

- Legal

- marketing of nuclear

- media

- opposition to nuclear

- PERSONAL STORIES

- politics

- politics international

- Religion and ethics

- safety

- secrets,lies and civil liberties

- spinbuster

- technology

- Uranium

- wastes

- weapons and war

- Women

- 2 WORLD

- ACTION

- AFRICA

- Atrocities

- AUSTRALIA

- Christina's notes

- Christina's themes

- culture and arts

- Events

- Fuk 2022

- Fuk 2023

- Fukushima 2017

- Fukushima 2018

- fukushima 2019

- Fukushima 2020

- Fukushima 2021

- general

- global warming

- Humour (God we need it)

- Nuclear

- RARE EARTHS

- Reference

- resources – print

- Resources -audiovicual

- Weekly Newsletter

- World

- World Nuclear

- YouTube

-

RSS

Entries RSS

Comments RSS