What Canada’s nuclear waste plan means for New Brunswick

by Mayara Gonçalves e Lima, January 20, 2026, https://nbmediacoop.org/2026/01/20/what-canadas-nuclear-waste-plan-means-for-new-brunswick/

Canada is advancing plans for a Deep Geological Repository (DGR) to store the country’s used nuclear fuel. In early 2026, the Nuclear Waste Management Organization (NWMO) entered the federal regulatory process by submitting its Initial Project Description — a major step in a project with environmental and social implications that will last for generations.

The implications of this project matter deeply to New Brunswickers because the province is already part of Canada’s nuclear legacy through the Point Lepreau Nuclear Generating Station. The proposed repository in Ontario is intended to become the final destination for used nuclear fuel generated in New Brunswick, currently stored on site at Point Lepreau.

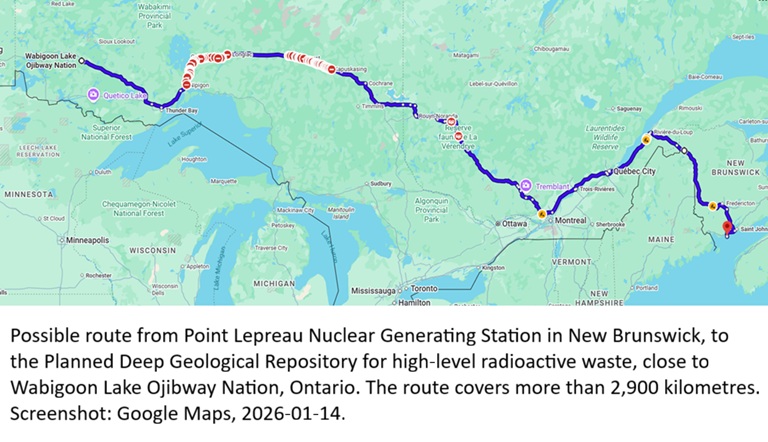

If the project goes ahead, highly radioactive nuclear waste would be transported across New Brunswick. Current NWMO plans envision more than 2,100 transport packages of New Brunswick’s used nuclear fuel travelling approximately 2,900 kilometres, through public roads in the province and across Canada, over a period of 10 to 15 years.

For many residents, the project raises long-standing concerns about safety, accountability, and cost — especially as NB Power continues to invest in nuclear technologies and considers new reactors. Decisions about the DGR will influence how long New Brunswick remains tied to nuclear power, carrying the risks of waste that remains hazardous far beyond any political or economic planning horizon.

This is a critical moment because public input is still possible — but the comment period window is narrow. Environmental organizations and community advocates are calling for extended consultation timelines, full transparency on transport risks, and meaningful consent from affected communities. Several groups have organized a sign-on letter that readers can review and support.

How New Brunswickers respond now will help determine whether these decisions proceed quietly — or with public accountability.

Unproven science and public concerns

Globally, no deep geological repository for high-level nuclear waste has yet operated anywhere on the planet. Finland’s Onkalo facility is often cited as the first of its kind, but it remains in testing, relies on unproven assumptions about geological containment, and will not be fully sealed for decades.

The lack of proven DGR experience matters for Canada because the proposed repository would be among the world’s earliest attempts to isolate high-level radioactive waste “forever,” despite the absence of any real-world proof that such facilities can perform as claimed. Canada’s decision therefore sets not only a national course, but a global precedent built on uncertain science and long-term safety assumptions.

The proposed DGR would be built 650 to 800 metres underground in northwestern Ontario, near the Township of Ignace and Wabigoon Lake Ojibway Nation (WLON), in Treaty #3 territory. Its purpose is to bury and abandon nearly six million bundles of highly radioactive used nuclear fuel, attempting to isolate them from the biosphere for hundreds of thousands of years.

The Nuclear Waste Management Organization describes the site selection as “consent-based,” but this framing raises difficult questions. Consent in economically marginalized regions — particularly where long-term funding, jobs, and infrastructure are promised — is not the same as free, prior, and informed consent, especially when the risks extend far beyond any western planning horizon.

In 2024, the Assembly of First Nations held dialogue sessions on the transport and storage of used nuclear fuel. Communities raised serious concerns that the proposed DGR could harm land, water, and air — all central to Indigenous culture and way of life.

Guided by ancestral knowledge and a duty to protect future generations, the Assembly warned that the DGR threatens sacred sites, ecosystems, and groundwater, including the Great Lakes. Climate change and natural disasters heighten these risks, exposing the limits of the current monitoring plan and prompting calls for life-cycle oversight.

A token consultation for a monumental project

As anticipated, the Initial Project Description raises serious concerns about the DGR process itself. One of the most serious flaws is the stark mismatch between the project’s scale and the time allowed for public input. Although the DGR is framed as a 160-year project with risks lasting far longer, communities, Indigenous Nations, and civil society groups have been given just 30 days to review the Initial Project Description, with submissions due by February 4.

Thirty days to read dense technical documents, consult communities, seek independent expertise, formulate questions, and respond meaningfully to a proposal that will affect land, water, and people for generations. This is not a generous consultation — it is the bare legal minimum under federal impact assessment rules.

While regulators emphasize that the overall review will take years, this early stage is crucial in shaping what will be examined and questioned later. Rushing public input at the outset risks reducing participation to a procedural checkbox rather than a genuine democratic process, particularly for a decision whose consequences cannot be undone.

The overlooked threat of waste transport

Another serious shortcoming in the project proposal is a failure to adequately address the nationwide transport of radioactive waste. Transporting highly radioactive material through communities by road or rail is central to the project and carries significant safety and environmental risks that remain largely unexamined.

By excluding radioactive waste transportation from the Initial Project Description, the Nuclear Waste Management Organization is effectively removing it from the scope of the comprehensive federal Impact Assessment. If transport is not formally included at this stage, it will not receive the same level of environmental review, public scrutiny, or interdepartmental oversight as the repository itself.

Instead, transportation would be left primarily to the Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission and Transport Canada to assess under the existing regulations — an approach that is fragmented and insufficient given the scale, duration, and risks of moving highly radioactive waste through communities.

The transport of radioactive waste is a critical yet often overlooked issue. As Gordon Edwards, president of the Canadian Coalition for Nuclear Responsibility notes, Canada has no regulations specifically governing the transport of radioactive waste — only rules for radioactive materials treated as commercial goods. This gap matters because radioactive waste is more complex, less predictable, and potentially far more dangerous.

Transporting high-level nuclear waste is inherently risky: the material remains hazardous for centuries, and accidents, equipment failures, extreme weather, security breaches, or human error can still occur despite careful planning. Unlike other hazardous materials, radioactive contamination cannot be easily contained or cleaned up, leaving land, water, and ecosystems damaged for generations. Even a single transport incident could have lasting, irreversible consequences for communities along the route.

Radiation risks extend beyond transport workers. People traveling alongside shipments may face prolonged exposure, while those passing in the opposite direction are briefly exposed in much larger numbers. Residents and workers along transport routes can experience repeated exposure, and accidents or unplanned stops could result in localized contamination. Emergency response is further complicated by leaks or hard-to-detect releases, with standard spill or firefighting methods potentially spreading contamination.

These risks are not hypothetical. Last summer, Gentilly-1 used fuel was transported from Bécancour, Quebec, to Chalk River, Ontario, along public roads — without public notice, consultation, Indigenous consent, or clear evidence of regulatory compliance — underscoring the ongoing risks to our communities.

According to the 2024 Assembly of First Nations report, at least 210 First Nations communities could be affected by shipments of radioactive waste traveling from nuclear reactors to the repository via railways and major highways, though the full scope may be even larger when considering watersheds and alternative routes.

Given this reality, it is unacceptable that the DGR Project Description largely ignores waste transport. Any credible assessment must examine how waste will be moved, who will be affected, what rules apply, who is responsible for oversight, and how workers, communities, and the environment will be protected in emergencies. It is the job of the Impact Assessment Agency of Canada to examine these plans in depth.

A high-stakes decision that demands public voice

Canada’s proposed Deep Geological Repository is one of the most ambitious and high-stakes projects in nuclear waste management. Framed as a permanent solution, it remains untested — no country has safely operated a deep repository for used nuclear fuel over the long term. Scientific uncertainty and multi-decade timelines make its risks profound and enduring.

Dr. Gordon Edwards warns: “The Age of Nuclear Waste is just beginning. It’s time to stop and think. […] we must ensure three things: justification, notification, and consultation — before moving any of this dangerous, human-made, cancer-causing material over public roads and bridges.”

Now is the moment for public voices to be heard. Legal Advocates for Nature’s Defence (LAND), an environmental law non-profit, has prepared a sign-on letter and accompanying press release calling for a more precautionary, transparent, and democratic approach to the Deep Geological Repository. This is your chance to have a say in decisions that could expose you, your neighbours, and your communities to serious environmental and health risks.

The letter urges federal regulators to extend public consultation timelines, require that the Impact Assessment Agency of Canada conduct a comprehensive Impact Assessment that includes the transportation of radioactive waste, and uphold meaningful consent and accountability.

New Brunswickers and allies across the country are encouraged to read the letter, add their names, and speak up before decisions are finalized. How Canada handles nuclear waste today will shape risks borne by our communities for generations.

The DGR is more than a technical project; it is a test of democratic process, scientific caution, and intergenerational responsibility. Canadians deserve a transparent, thorough, and precautionary approach to ensure that decisions made today do not compromise the safety of future generations.

Mayara Gonçalves e Lima works with the Passamaquoddy Recognition Group Inc., focusing on nuclear energy. Their work combines environmental advocacy with efforts to ensure that the voice of the Passamaquoddy Nation is heard and respected in decisions that impact their land, waters, and future.

No comments yet.

-

Archives

- January 2026 (288)

- December 2025 (358)

- November 2025 (359)

- October 2025 (376)

- September 2025 (258)

- August 2025 (319)

- July 2025 (230)

- June 2025 (348)

- May 2025 (261)

- April 2025 (305)

- March 2025 (319)

- February 2025 (234)

-

Categories

- 1

- 1 NUCLEAR ISSUES

- business and costs

- climate change

- culture and arts

- ENERGY

- environment

- health

- history

- indigenous issues

- Legal

- marketing of nuclear

- media

- opposition to nuclear

- PERSONAL STORIES

- politics

- politics international

- Religion and ethics

- safety

- secrets,lies and civil liberties

- spinbuster

- technology

- Uranium

- wastes

- weapons and war

- Women

- 2 WORLD

- ACTION

- AFRICA

- Atrocities

- AUSTRALIA

- Christina's notes

- Christina's themes

- culture and arts

- Events

- Fuk 2022

- Fuk 2023

- Fukushima 2017

- Fukushima 2018

- fukushima 2019

- Fukushima 2020

- Fukushima 2021

- general

- global warming

- Humour (God we need it)

- Nuclear

- RARE EARTHS

- Reference

- resources – print

- Resources -audiovicual

- Weekly Newsletter

- World

- World Nuclear

- YouTube

-

RSS

Entries RSS

Comments RSS

Leave a comment