‘Radioactive patriarchy’ documentary: Women examine the impact of Soviet nuclear testing

During the time of the detonations, approximately 1.5 million people lived near the sites, despite Soviet claims that the area was uninhabited.

In the ensuing decades, diagnoses of cancers, congenital anomalies and thyroid disease affected the surrounding communities at an alarming rate, particularly for women.

November 17, 2025, Rebecca H. Hogue, Assistant Professor, Department of English, University of Toronto https://theconversation.com/radioactive-patriarchy-documentary-women-examine-the-impact-of-soviet-nuclear-testing-256775

Following recent comments on nuclear testing by United States President Donald Trump and Russian leader Vladimir Putin, it’s more important than ever to remember that nuclear detonations — whether in war or apparent peace time — have long-lasting impacts.

Over a 40-year period, up to 1989, the Soviet Union detonated 456 nuclear weapons in present-day Kazakhstan (or Qazaqstan, in the decolonized spelling)

During the time of the detonations, approximately 1.5 million people lived near the sites, despite Soviet claims that the area was uninhabited.

In the ensuing decades, diagnoses of cancers, congenital anomalies and thyroid disease affected the surrounding communities at an alarming rate, particularly for women.

A new independent documentary, JARA Radioactive Patriarchy: Women of Qazaqstan, examines the impacts of nuclear weapons in Qazaqstan. Jara means “wound” in the Qazaq language.

The film is directed by Aigerim Seitenova, a nuclear disarmament activist with a post-graduate degree in international human rights law who co-founded the Qazaq Nuclear Frontline Coalition. Seitenova grew up in Semey (formerly called Semipalatinsk), Qazaqstan.

Close to Semey is the Semipalatinsk nuclear test site, also known as The Polygon, in Qazaqstan’s northeastern region. It’s an area slightly smaller than the size of Belgium — approximately 18,000 square kilometres — in the former Kazakh Soviet Socialist Republic.

Nuclear Truth Project

Seitenova introduced her film in March 2025 at the United Nations headquarters in New York, hosted by the Nuclear Truth Project. The documentary premiere was a side event at the Third Meeting of States Parties to the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.

As a literary and cultural historian who examines narratives of the nuclear age, I attended the standing-room-only event alongside many delegates from civil society organizations.

Nuclear disarmament activist

Seitenova, who wrote, directed and produced JARA Radioactive Patriarchy on location in Semey, aims to bring women’s nuclear stories to Qazaqstan and international audiences.

The 30-minute documentary features intimate interviews with five Qazaq women. The film shares the women’s fears, grief and the ways they have learned to cope, as well as reflections from Seitenova filmed at the ground-zero site.

For Seitenova, it was essential that the film be in Qazaq language.

“Qazaq language, like Qazaq bodies,” she said in an interview after the premiere, “were considered ‘other’ or not valuable.” Seitenova acknowledged it was also important to show a Qazaq-language film at the UN, as Qazaq is not an official UN language like Russian.

Women consensually share experiences

One of Seitenova’s directorial choices was not just what or who would be seen, but specifically what would not be seen in her film.

“I’m really against sensationalism,” said Seitenova. “If you Google ‘Semipalatinsk’ you will see all of these terrible images of children and fetuses.”

Seitenova accordingly does not show any of these images in her film, and instead focuses on women consensually sharing their experiences.

Seitenova explained how narratives regarding the health effects in Semey are often disparaged. When others learn she is from Semey, Seitenova shared, some will make insensitive jokes like “are you luminescent at night?” — making nuclear impact into spectacle, instead of taking it as a serious health issue.

These experiences have propelled her to take back the narrative of her community by correcting misconceptions or the minimization of harms. Instead, she brings attention to the larger structural issues.

“Everything was done by me because I did not want to invite someone who would not take care of the stories of these women,” said Seitenova.

Likewise, Seitenova only interviewed participants who had already made decisions to speak out about nuclear weapons. She did this so as not to risk retraumatizing someone by asking them to discuss their illnesses, especially for the first time on camera.

Global legacy of anti-nuclear art, advocacy

Seitenova also wanted to show a genealogy of women speaking out about nuclear issues in Qazaqstan, contributing to a global legacy of anti-nuclear art and advocacy.

The film features three generations of women, including Seitenova’s great aunt, Zura Rustemova, who was 12 at the time of the first detonations.

As part of this genealogy of nuclear resistance, the film includes footage of a speech from the Qazaq singer Roza Baglanova (1922-2011), who rose to prominence singing songs of hope during the Second World War.

Effects felt into today

JARA Radioactive Patriarchy shows how the impacts of nuclear weapons are felt intergenerationally into the present.

“Many women lost their ability to experience the happiness of motherhood,” interviewee Maira Abenova says in the film. Abenova co-founded an advocacy group representing survivors of the detonations, Committee Polygon 21.

Other interviewees shared how often men left their wives and children who were affected by nuclear weapons to begin a new family with someone else.

Seitenova looks at the roles of women and mothers not just as protectors, but also as those who have launched formidable advocacy.

The film highlights the towering monument in Semey, “Stronger than Death,” dedicated to those affected by nuclear weapons.

The Semey monument depicts a mother using her whole body to protect her child from a mushroom cloud. Just like the monument, Seitenova and the women in her documentary use the film to show how women have been doing this advocacy work in the private and public spheres, with their bodies and with their words.

“I want to show them as being leaders in the community, as changing the game,” Seitenova said.

While the film brings a much-needed attention to the gendered impact of nuclear weapons in Qazaqstan, she makes clear that this is, unfortunately, not an issue unique to her homeland or just to women.

“The next time you think about expanding the nuclear sector in any country” Seitenova said, “you can think about how it impacts people of all genders.”

Leah McGrath Goodman, Tony Blair and issues on torture (with added radiation)

Published by arclight2011- date 15 Sep 2012 -nuclear-news.net

[…]

Accusations: Despite the mockery of the film Borat, leaked U.S. cables suggest the country was undemocratic and used torture in detention

Other dignitaries at the meeting included former Italian Prime Minister and ex-EU Commission President

Romano Prodi. Mr Mittal’s employees in Kazakhstan have accused him of ‘slave labour’ conditions after a series of coal mining accidents between 2004 and 2007 which led to 91 deaths.

[…]

Last week a senior adviser to the Kazakh president said that Mr Blair had opened an office in the capital.Presidential adviser Yermukhamet Yertysbayev said: ‘A large working group is here and, to my knowledge, it has already opened Tony Blair’s permanent office in Astana.’

It was reported last week that Mr Blair had secured an £8 million deal to clean up the image of Kazakhstan.

[…]

Mr Blair also visited Kazakhstan in 2008, and in 2003 Lord Levy went there to help UK firms win contracts.

[…]

Max Keiser talks to investigative journalist and author, Leah McGrath Goodman about her being banned from the UK for reporting on the Jersey sex and murder scandal. They discuss the $5 billion per square mile in laundered money that means Jersey rises, while Switzerland sinks.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gA_aVZrR5NI&feature=player_detailpage#t=749s

And as well as protecting the guilty child sex/torturers/murderers of the island of Jersey I believe that they are also protecting the tax dodgers from any association.. its just good PR!

FORMER Prime Minister Tony Blair was reportedly involved in helping to keep alive the world’s biggest takeover by Jersey-incorporated commodities trader Glencore of mining company Xstrata.

11/September/2012

[…]

Mr Blair was said to have attended a meeting at Claridge’s Hotel in London towards the end of last week which led to the Qatari Sovereign wealth fund supporting a final revised bid from Glencore for its shareholding. Continue reading

Nuclear waste to nuclear reactor: The case of Russia in Kazakhstan

Ayushi Saini, 11 Jul 2025 https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/nuclear-waste-nuclear-reactor-case-russia-kazakhstan

Facing energy deficits, Kazakhstan turns to Russia’s Rosatom for nuclear

power despite a history of environmental and dependency concerns.

After shutting down its last Soviet-era reactor in 1999, Kazakhstan is now on the cusp of returning to nuclear energy. Long reliant on non-renewables and electricity imports, the country faces rising energy demands and an urgent need to diversify its energy sources.

In October 2024, a national referendum strongly backed the construction of a nuclear power plant, with Russia’s Rosatom ultimately selected to lead the project. The decision marks a major shift in the country’s energy strategy and reaffirms Russia’s enduring influence in Central Asia’s high-stakes infrastructure sector.

However, the decision raises several concerns, including environmental risks, increased energy dependence on Russia, and the revival of unsettling memories of Soviet-era nuclear contamination in Kazakhstan. Understanding why Kazakhstan is turning back to nuclear power and why it chose Russia for its first Nuclear Power Plant (NPP)merits a closer look at the strategic and geopolitical factors behind this move.

Nuclear past, nuclear future

Kazakhstan’s journey with nuclear technology is fraught and painful. As a Soviet republic, it served as a major testing ground, most notably at the Semipalatinsk Test Site, where more than 450 atmospheric and underground nuclear detonations took place. This placed a heavy toll on the environment of Kazakhstan, without the nuclear waste having been taken care of by the Soviet Union.

From 1979 to 1999, Kazakhstan hosted a high-neutron Soviet nuclear power plant. After independence in 1991, Kazakhstan dismantled its arsenal and embraced nuclear non-proliferation with the Semipalatinsk test site closing in the same year.

Now, facing power deficits, it is returning to nuclear power for civilian use. The new plant will be built near the village of Ulken by Lake Balkhash – a site chosen for its geographical viability, including proximity to water access. However, environmental concerns persist. Kazakhstan lacks the domestic capacity to manage nuclear waste and must rely on external actors. Despite its past role in Kazakhstan’s nuclear contamination, Russia has reemerged as a key partner in the country’s nuclear revival.

Illusion of a consortium

Astana designated Rosatom to lead the construction of its first NPPafter a competitive bidding process involving China’s China National Nuclear Commission (CNNC), France’s Electricité de France (EDF), and Korea Hydro & Nuclear Power. While authorities claim the formation of an international consortium, Rosatom remains the undisputed leader, reflecting both its technological edge and Moscow’s strategic weight in Astana. Kazakhstan claims that it is the exclusive owner, operator, and supplier of uranium fuel, with complete control over the technological processes of its upcoming nuclear power plant.

Meanwhile, China has been selected to lead the second nuclear power plant, with feasibility studies underway. Kazakhstani officials argue that China is best suited to cooperate with Russia, given their regional rapport. Though framed as multinational, the consortium appears largely symbolic, aimed at balancing ties with major powers. Rosatom’s financing offer further tightens Russia’s grip on Kazakhstan’s energy future.

Why Russia?

Kazakhstan’s decision to shift to nuclear power comes amid a growing electricity production deficit. The country faces a projected shortfall of over 6 GW by 2030, making energy security urgent. The selection of Rosatom to carry out the construction is officially justified by Kazakhstani authorities, given Russia’s global leadership in nuclear technology and its advanced VVER 3+ generation reactors, which are already in operation across several domestic and international sites. Rosatom was deemed to have submitted “the most optimal and advantageous proposal.”

This outcome is not surprising. Talks between Kazakhstan and Russia on nuclear cooperation began in 2011, leading to a feasibility study and a series of agreements. In 2014, an MoU was signed for constructing a VVER-based plant with a capacity of up to 1200 MWe. Kazakhstan also holds a 25% stake in parts of Russia’s nuclear energy sector, and Rosatom’s subsidiary, Uranium One, is already active in Kazakhstan’s uranium mining. Additionally, Russia was Kazakhstan’s top electricity supplier in 2024, exporting 4.6 billion kWh.

Kazakhstan’s alignment with Russia reflects shared Soviet-era technical standards, institutional continuity, and a workforce fluent in the Russian system. Rosatom’s reactors are cost-effective, geographically proximate, and supported by uranium supply and tech transfer offers. Russian remains a common language among elites, and Rosatom’s regional presence, including in Uzbekistan, adds further appeal.

As Kazakhstan’s oil and gas sector is dominated by Western companies (such as ENI, Shell and Chevron, and Russian Lukoil only having 13% stakes in Kashagan Oil Field), choosing Russia for nuclear energy helps Astana maintain a strategic balance and avoid overdependence on any one bloc, without triggering Western sanctions, as Rosatom remains unsanctioned.

Balancing act

Kazakhstan’s decision to pursue nuclear power under Rosatom’s leadership marks a turning point in both its energy strategy and ties with Russia. While the project aims to ease electricity shortages and boost Kazakhstan’s global energy profile, it also deepens reliance on Russia, whose regional influence had waned after the Ukraine crisis.

Although Kazakhstan seeks diverse partnerships – “middle power” diplomacy being a recent fous – geographic and historical ties continue to draw it toward Moscow. The inclusion of other countries in the proposed consortium reflects Astana’s multi-vector foreign policy, an attempt to maintain geopolitical flexibility while meeting infrastructure needs. As the consortium’s lead, Rosatom reinforces its influence over the region’s energy and political landscape. Yet, Kazakhstan’s visible effort to balance Russia and China suggests it won’t sideline either in its strategically vital energy sector.

Atomic bombs destroyed their lives – now they want Russia to pay

“People living around the test site “became unwitting test subjects, and their lives were treated with casual disregard due to racism and ignorance,”

“It was a crime of negligence, whereby secrecy, control, and the acquisition of more powerful nuclear weapons were prioritised over the lives of local people.”

Amid calls to restart nuclear testing, families are still suffering from mutations passed down through the generations

Arthur Scott-Geddes. Simon Townsley Photographer, in Semey, Telegraph, 21 May 2025

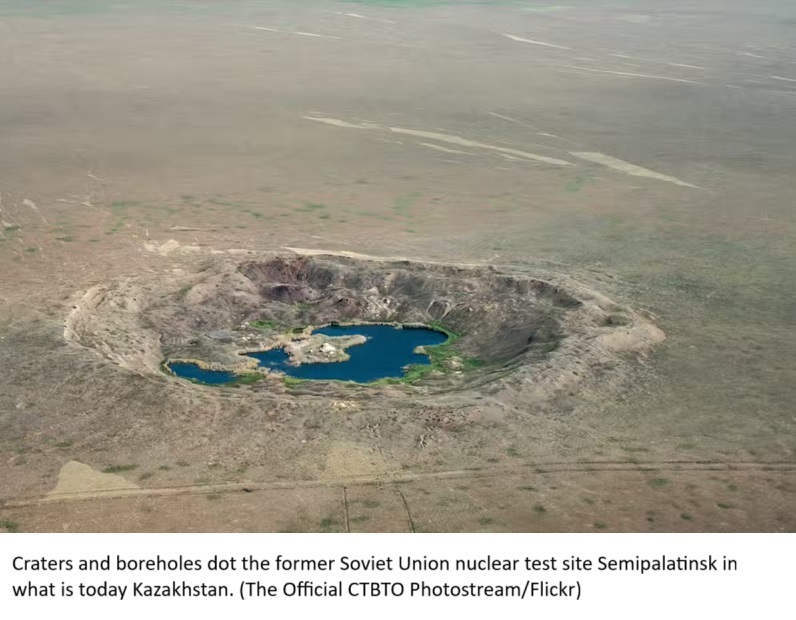

The Geiger counter came to life as we trudged toward the lip of the crater, its clicks becoming frantic before giving way to an alarm.

“This is the Atomic Lake,” said the hazmat-suited guide, throwing out his arms against the wind to encompass the circular expanse of water below. “Don’t get too close to the edge.”

Sixty years ago a nuclear bomb ten times more powerful than the one that destroyed Hiroshima exploded at the bottom of a 178-metre shaft in this remote (but not unpopulated) corner of Kazakhstan.

The blast excavated a basin a quarter of a mile wide and several hundred feet deep, sending up a plume of pulverised rock and radioactive material that was detected as far away as Japan.

It was not a one off. The hydrogen bomb was one of 456 nuclear weapons detonated by the Soviet Union at the Semipalatinsk Test Site, a 7,000 square mile swathe of steppe known as the Polygon.

The tests started in 1949 and continued right up until 1989 and the fall of the Berlin wall. They account for a quarter of all the nuclear explosions in history, creating an ongoing health crisis of a scale and nature that is hard to fathom.

The Kazakh authorities estimate that one-and-a-half million people living in nearby cities, towns and villages were exposed to the residual fallout.

The region has elevated rates of cancer, heart disease, birth defects and fertility problems – all linked to the tests. Suicides are common and the area’s graveyards are filled with people who died young.

But as well as sickening those who were directly exposed, the fallout has worked its way into the population’s DNA, leading to mutations that have been passed down through the generations.

‘There were so many children born with different mutations’

Almost everyone who grew up in Semey, a city of about 350,000 that lies only 75 miles from the Polygon, was affected in some way by the testing programme.

Olga Petrovskaya, the 78-year-old chair of Generation, a campaign group founded in 1999 to petition the government for greater support for the victims of the tests, remembers explosions shaking the city.

“We would be taken out of the classroom because they were worried about the windows shattering,” she said. “But nobody would explain why it was happening.”

White dust would sometimes fall on the city, causing sores to form on exposed skin. It was not long before people started dying.

“When we were six years old, at nursery school, there was a girl who died of leukaemia,” she said. “And then at [primary] school our classmates were also dying of cancerous diseases.

“Cancer became a very common diagnosis – there is no family that hasn’t been affected by it – and there were so many children born with different mutations.”

Ms Petrovskaya lost her brother, her aunt and her in-laws to cancer in the 1960s. She herself suffered numerous miscarriages and still has debilitating headaches and dizzy spells that she believes are linked to the radiation.

Her group of activists has dwindled as its members succumbed to their illnesses. There are now only a handful of them left.

The Soviet testing programme has been frequently criticised for its recklessness.

For instance, the first test of a two-stage hydrogen bomb created a blast much more powerful than anticipated, causing a building to collapse and killing a young girl in Kurchatov, the closed-off city 40 miles away where the tests were directed from

But the scientists and military personnel responsible understood the risks inherent in what they were doing. Modelling has shown that people who lived through all 456 tests received doses of radiation up to 120 times greater than survivors of the Hiroshima bombing.

“The Soviet authorities were absolutely not ignorant of the dangers of nuclear weapons testing,” said Dr Becky Alexis-Martin, a Lecturer in Peace, Science, and Technology at the University of Bradford.

“The tests occurred long after the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings, and records from the time reveal that the scientists involved in the Polygon tests had expert understandings of the impacts of ionising radiation on health.”

People living around the test site “became unwitting test subjects, and their lives were treated with casual disregard due to racism and ignorance,” added Dr Alexis-Martin

“It was a crime of negligence, whereby secrecy, control, and the acquisition of more powerful nuclear weapons were prioritised over the lives of local people.”

There is a growing body of evidence showing that radiation-induced mutations can be passed down multiple generations.

In 2002, an international study of 20 families living around the Semipalatinsk test site showed that exposure to fallout nearly doubled the risk of inherited gene mutations.

“Genetic consequences manifest in many different ways and any gene can be affected by radioactive exposure. Some gene changes are invisible beyond our DNA – but others can have harmful and intergenerational impacts,” said Dr Alexis-Martin.5

“We often think of birth defects when we think of radiation exposure, but hereditary heart conditions, blindness, and deafness can also arise.”

Today many Kazakh families still bear the marks of the tests several generations after the explosions stopped.

‘I will not live much longer’

Read more: Atomic bombs destroyed their lives – now they want Russia to pay

Asel Oshakbayeva was born in 1997, eight years after the last atomic detonation at the Polygon.

Yet she soon began to have seizures, and at the age of three months suffered a brain haemorrhage that left her blind and unable to speak, move or eat.

“She was in a coma, she couldn’t see anything,” said her mother, Sandugush.

The family sold their home and two cars to fund experimental surgical treatment in Russia that, after 14 operations, repaired damage to her optic nerve, partly restored her speech and made it possible for her to eat again.

But she remains totally dependent on her mother, and the pair left Semey and now live cheek-by-jowl with five other relatives in a small flat in Astana, the capital.

Sandugush, like her parents before her, was exposed to high levels of radiation while living near the Polygon.

In total, three generations of her family have now been officially recognised as victims of the testing, including her daughter. Her husband died of cancer 10 years ago, and she herself has a host of unusual health complaints.

“I will not live much longer,” she said, gesturing to her side where surgeons removed cancerous tumours from her breast and lymph nodes.

She now worries who will look after her daughter in the future. “She has the mind of a ten-year-old. If I die, what will happen?”

Despite the high prevalence of disability in the communities affected by the Polygon, a stigma around the children born with deformities persists.

Maira Zhumageldina, 56, lived for a time in the area of maximum radiation risk and gave birth to her daughter Zhannur in 1992.

Zhannur’s ribcage, spine and limbs never properly formed, leaving her permanently disabled – unable to walk, talk or feed herself.

When the extent of Zhannur’s disability became clear, Ms Zhumageldina came under pressure to give her up, even from her own family.

“When I had Zhannur about 13 or 14 children were born with different kinds of disabilities, so some were abandoned and some died at early ages,” she said.

“My parents-in-law said: ‘Why don’t you leave her?’ But I said ‘this is my child’ I could never leave her.”

A well-thumbed album of photographs documents the 28 years that Ms Zhumageldina devoted to caring for her daughter.

She trained as a massage therapist to ease her pain, and took her to Astana for specialised treatment……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

‘The slow genocide’

……people whose families have been torn apart by the tests accuse the government of a “genocide” by inaction.

Reluctant to cough up the cash to properly support the hundreds of thousands of people sickened by the radiation and unwilling to press Russia for help in fear of provoking a diplomatic row, the government, they say, is simply waiting for them to die.

………Most of the fallout came their way – the Soviet scientists in Kurchatov made sure not to detonate any weapons while the wind was blowing towards them.

Hardly anyone here lives to retirement age, and cancer and birth defects are common.

“It’s a genocide,” said Acen Kusayenuli, 59, a veteran of the war in Afghanistan who recently had a portion of his lung removed after being diagnosed with cancer. He cannot afford chemotherapy so instead chews herbs to fight the disease.

“We were just like mice,” he said. “Why else would they not relocate the people and animals? They wanted to see how we would be affected.”

Even the landscape has suffered……..

the villagers, always kept in the dark about what was going on, bore the burden of death with a strange stoicism common to many parts of the former Soviet Union.

“We just accepted that whoever gets sick, gets sick,” she said……………………..

“The nuclear weapons tests were undertaken in the knowledge that the local ethnic Kazakhs could be harmed or even gradually eradicated,” said Dr Alexis-Martin.

“The lack of impetus and action across the decades by successive Soviet, Russian, and Kazakhstan governments and the global community amounts to ‘slow genocide’ – this arises when an ethnic or cultural group is gradually and systematically destroyed due to cumulative and sustained harm over time.”

Seventy-five miles further down the road is the village of Kaynar, which sits in the shadow of a rock formation overlooking the test site. Older residents remember climbing to the top to watch the explosions. ……………………………………………………………

Dr Saule Isakhanova, the head doctor of the Abralinski Regional Hospital which looks after around 2,100 people in Kaynar and the surrounding villages, said nearly half of her patients had health problems linked to the tests.

Her husband, the former mayor, was one of those who used to go out into the steppe to collect grass. He now has bowel cancer.

She said the effects of the tests could continue to harm people living in the area for a long time.

“Research shows that particles of these elements can remain in the dust for 300,000 years,” she said, referring to the radionuclides released by the bombs. “Those particles, once you breathe them in, they get into your bones.”

While much of the research attention has so far focused on rates of cancer and birth defects, little has been done to understand the prevalence of developmental disorders among children affected by the tests.

……………………………………………………..Dr Talgat Moldagaliyev, the former Director of the Institute of Radiation Medicine and Oncology in Semey, said more work is needed to understand the effects the tests are continuing to have.

“It’s a living experimental zone, but not enough research has been done.”

‘It should never happen again’

Most of the victims of the Polygon only learned the truth about what had been happening to them after the Soviet Union collapsed and Kazakhstan gained independence.

That moment gave rise to Kazakhstan’s first civil society movement, which connected survivors of the Polygon tests with communities affected by American nuclear testing in Nevada.

Over 35 years since the last nuclear explosion at the Polygon, there is a renewed push to win justice for those affected by the radiation.

Maira Abenova, the founder of Committee Polygon 21, an advocacy group representing the victims, lost her mother, brother, sister and husband to diseases related to the Polygon and now suspects she has cancer herself.

She wants the world to recognise that the suffering did not end with the closure of the test site.

“Currently the law recognises as a survivor of the nuclear tests only those people who lived in four regions around the Polygon from 1949 to 1991,” she said, referring to a law brought in in 1992 which gave people who qualified a “radiation passport” certifying their exposure to the radiation.

Those given the small, beige documents, which bear a blue mushroom cloud stamp on the cover, receive a small amount of compensation and other benefits including longer holidays.

While older survivors of the tests say the system worked at first, many of the families The Telegraph spoke to, particularly those in the hard-hit villages, said it was difficult to get official recognition for their children.

Rising medical costs far outstrip benefits worth around $40 a month and moving away from the villages, even to seek better medical care, disqualifies survivors from support.

Ms Abenova has been petitioning government agencies, who are more interested in collaborating with Russia on nuclear energy and turning the test site into a dark tourism destination, to take action on a grander scale.

“You cannot solve the problem just by paying small additional payments, you have to upgrade the economy in the region,” she said.

United Nations resolutions and the sustainable development goals (SDGs) should also be used to improve the lives of those living in the areas affected by the tests, and a new law is needed “which recognises all the survivors,” she said.

Committee Polygon 21 was among several Kazakh civil society groups to appeal to the UN in New York urging global action on justice for the testing victims.

After Vladimir Putin, the Russian President, withdrew his country’s ratification of the global treaty banning nuclear weapons tests, and with advisers of Donald Trump urging him to restart US testing, Ms Abenova hopes her work will also energise calls for disarmament.

“Kazakhstan suffered from nuclear tests […] Our people should use this opportunity to appeal to other countries that it should never happen again,” she said.

Meanwhile, how safe it is to live in the area around the Polygon remains unclear.

The site itself has been picked over by scavengers looking for – often highly irradiated – scrap metals.

Some 116 bombs were detonated in the atmosphere, but 340 exploded underground, and a secretive joint US-Russian-Kazakh cleanup programme to secure fissile material and even bomb components left behind by the Soviets in tunnels and shafts was only made public after it ended in 2012.

Those living nearby still do not know if their food and water is safe.

……………………..https://www.telegraph.co.uk/global-health/terror-and-security/soviet-union-nuclear-testing-atomic-bomb-kazakhstan/

Kazakhstan’s Nuclear Power Vote: Many Questions, But Just One On The Ballot

Radio Free Europe 5th Oct 2024

ALMATY, Kazakhstan — Kazakh voters will head to the polls on October 6 to decide whether to approve the construction of the first nuclear power plant in Kazakhstan — the world’s largest producer of uranium.

And the question on the ballot will be just that: “Do you agree to the construction of a nuclear power plant in Kazakhstan?”

But the debate surrounding nuclear energy is far more complex, taking in the heavy legacy of Soviet-era nuclear tests, long-standing nuclear-phobia, and unanswered questions around the companies — and countries — that would build the plant if voters endorse it.

Ahead of the first referendum in Central Asia on nuclear power, RFE/RL takes a closer look at that conversation.

What The Government Says

In many countries, national referendums can divide governing coalitions and spark cabinet resignations, but there is no sign of anything like that in Kazakhstan — the political elite is firmly behind the plan to build a nuclear power plant.

That extends from the government to the legislature, where all six parties support the idea, and where at least one lawmaker who initially opposed the plan now says he changed his mind.

The government’s main argument is that only nuclear power has the capacity to provide near-zero carbon energy on the scale required to cover a power deficit that grows year-on-year, especially in the southern half of the country.

Why Not Renewables?

While wind and solar’s overall share of the fossil-fuel-heavy national energy mix has grown to around 6 percent in recent years, Energy Minister Almasadam Satkaliev argues that renewables’ dependence on “natural and climatic conditions” make them too “unpredictable” on a large scale.

President Qasym-Zhomart Toqaev first floated the idea of using nuclear power in 2019.

Like other officials, he has assured Kazakhs that a future nuclear plant will be built with the latest technology to ensure the highest safety standards.

As the world’s largest uranium producer, he says it is time for Kazakhstan to move up the nuclear-fuel cycle.

Why Hold A Referendum?

That is a good question, given that any sort of popular vote carries a protest risk, and Kazakhstan’s authoritarian regime has only recently held parliamentary elections (March 2023) and a presidential election (November 2022).

But the country’s leadership knows that the issue is contentious — not least because the nation’s introduction to nuclear power began with the Soviet Union’s first nuclear bomb test in 1949, with hundreds more taking a terrible human and environmental toll in the northeastern Semei region……………………………………….

Is There A ‘No’ Campaign?

To the extent that Kazakhstan allows such things, there is.

But nuclear naysayers have been repeatedly blocked from holding demonstrations against the plan in various cities, and most recently found that a hotel in the largest city, Almaty — where they had earlier agreed to hold an event — was suddenly unwilling to host them.

At least five Kazakh activists opposed to nuclear power have been placed in pretrial detention on charges of plotting mass unrest early this month, while others have faced administrative punishment. https://www.rferl.org/a/kazakhstan-nuclear-power-referendum/33146657.html

World’s largest uranium miner warns Ukraine war makes it harder to supply west

Kazatomprom’s chief executive has warned that Russia’s war on

Ukraine is making it harder for the world’s largest uranium producer.

Kazatomprom’s chief executive has warned that Russia’s war on Ukraine

is making it harder for the world’s largest uranium producer to keep

supplying the west as the gravitational pull towards Moscow and Beijing

grows stronger.

Meirzhan Yussupov, chief of the Kazakh state miner, said

that sanctions caused by the war had created obstacles to supplying western

utilities. “It is much easier for us to sell most, if not all, of our

production to our Asian partners — I wouldn’t call [out] the specific

country . . . They can eat up almost all of our production, or our

partners to the north,” he told the FT.

FT 10th Sept 2024

https://www.ft.com/content/b8b34ec4-20ca-4c00-937b-fc620ae7503e

Controversy Surrounds Kazakhstan’s Nuclear Referendum

Oil Price, By RFE/RL staff – Sep 04, 2024,

- Kazakhstan has allocated $32 million for a referendum on the construction of a nuclear power station.

- The referendum, scheduled for October 6, has sparked controversy due to concerns over nuclear safety and Russia’s potential involvement.

- Despite public opposition, the Kazakh government is pushing forward with the plan, highlighting the country’s tightly controlled political environment.

…………………………………………….Mustafina’s deputy Konstantin Petrov said more than 12 million Kazakh citizens are eligible to vote at more than 10,000 voting sites across the country and 78 stations will be set up in different countries for Kazakh citizens residing abroad.

Only one question will be asked in the referendum: “Do you agree that Kazakhstan needs to construct a nuclear power station?”

Many in Kazakhstan expect that the answer will be “yes,” considering the country’s tightly controlled political environment.

But the push to build a nuclear power plant has been met by significant opposition despite apparent efforts to silence dissent on the issue. In recent weeks, several activists known for their stance against the nuclear power station’s construction have been prevented from attending public debates on the matter.

Nuclear-power-related projects have been a controversial issue in Kazakhstan, where the environment was severely impacted by operations at the Soviet-era Semipalatinsk nuclear test site from 1949 to 1991 and the Baikonur spaceport, which is still being operated by Moscow.

Hours before his decree was made public on September 2, President Toqaev reiterated his support for the plan to build a nuclear power station.

There was no official information about the site of the future nuclear station, but a public debate was held last year in the village of Ulken on the shore of the Lake Balkhash in the southeastern region of Almaty about the possibility of constructing a nuclear power station there.

The idea to build a nuclear power station in Kazakhstan has been circulating in the country for years, leading to questions regarding what countries would be involved in the project.

Kazakh officials have tried to avoid answering the question, saying the decision would be made after a referendum.

Shortly before launching its ongoing invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Russia proposed its Rosatom nuclear agency to be Kazakhstan’s major partner in the project. https://oilprice.com/Alternative-Energy/Nuclear-Power/Controversy-Surrounds-Kazakhstans-Nuclear-Referendum.html

Kazakh Internet users mostly rejected the idea of Rosatom’s involvement, citing the legacy of the 1986 Chernobyl nuclear disaster and Russia’s gaining control over the Zaporizhzhya nuclear power plant in Ukraine as examples of Russia’s attitude toward nuclear safety.

Young Changemakers Advocate for Nuclear-Free Future through Educational Journey in Kazakhstan

The Astana Times – bringing Kazakhstan to the world, By Assel Satubaldina , 29 July 2024

ASTANA—A group of 20 young changemakers from Kazakhstan and Germany recently embarked on a week-long educational journey through Kazakhstan to explore the country’s nuclear past, meet policymakers, and talk to affected communities.

The tour took the group to the ministerial halls in Astana, activists in Almaty, researchers, and the nuclear-affected communities in Semei, which was once the site for the Soviet-run nuclear test site. This educational tour, organized by the Friedrich Ebert Foundation in Kazakhstan, ICAN Germany, and Kazakhstan’s STOP (Steppe Organization for Peace) youth initiative, aimed to foster a deeper understanding of nuclear non-proliferation and amplify the voices of affected communities.

Kazakhstan’s Semipalatinsk nuclear test site was a venue for the Soviet Union to test nuclear weapons. Official data indicates that 456 nuclear tests between 1949 and 1989, including 340 underground and 116 atmospheric tests, were conducted at the test site, with an area of 18,300 square kilometers.

Around 1.5 million people have been affected by radiation exposure over the years, including health consequences such as an increase in cancer rates, birth defects, and other radiation-related illnesses among the local population. The long-term effects are still present for generations.

Meeting with government officials in Astana

Astana was the first stop on the trip. The group visited the Kazakh Ministry of Foreign Affairs. There, Arman Baissuanov, the head of the ministry’s international security department, briefed them on the country’s nuclear history and its leading role in global non-proliferation efforts. He also discussed Kazakhstan’s role in the Central Asian Nuclear Weapon Free Zone and the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW).

Among other officials, the group met with Roman Podoprigora, a judge of the Constitutional Court of Kazakhstan, who spoke about recommended changes to the 1992 law on those affected by the nuclear tests, and Nurlan Auesbaev, a member of the Parliament.

Yerdaulet Rakhmatulla, co-organizer of the study tour, described it as a positive sign that civil society representatives could visit the ministry and productively discuss the nuclear politics and more. According to him, it is quite a rare occasion.

“I think just this step from their side was a great sign of progress in our bilateral relationships as state, as government and civil society,” he said in a comment for this story.

Officially titled the law on social protection of citizens who suffered from nuclear tests at the Semipalatinsk nuclear test site, the document envisioned measures to address the severe health and social impacts. However, experts say the law has many shortcomings, including a limited scope of financial compensation, which is insufficient to cover the long-term health needs of the affected population. The law’s criteria to identify affected individuals have also been seen as too narrow.

Сonfronting the human impact of nuclear testing

Understanding Kazakhstan’s tragic nuclear past would not be complete without visiting the region where thousands of people witnessed the tests firsthand and have borne the consequences for many years since. In Semei, the young people met with people still grappling with the legacy of the Soviet-era tests, listening to their stories that, for some reason, often remain unheard.

Maira Abenova, a survivor of the Soviet nuclear tests in Semei and founder of the Polygon 21, an institution that advocates for the rights of Semipalatinsk nuclear test survivors, helped the group to meet those affected in Semei and Astana.

During the meeting in Semei, many of the survivors reported on their health problems, such as cancer and heart disease, according to a press report from ICAN Germany. They said they hope their voices will be heard internationally. Their voices “do not yet reach as far as those of Hiroshima and Nagasaki,” say the survivors.

For Rakhmatulla, these meetings were “extremely special………………………………………………………………………………………………..

Lessons learned

Janina Ruther, a participant of the tour and project manager at ICAN Germany, spoke to The Astana Times, sharing her impressions and key takeaways from the educational tour.

Because of her experience with ICAN, she got to know more about Kazakhstan and the country’s history with nuclear weapons.

Ruther said what made the trip so special was the variety of places they visited and the diverse range of people they spoke to in different contexts.

“That was so special, and it made it a once-in-a-lifetime experience,” she added. “I think I don’t have words for that because we talked to so many people who were actually surviving all these tests. It was so brave that they talked to us because I cannot imagine how hard it must be.”

She also shared meeting young people at the universities and experiencing the night train journey was unforgettable.

She described the tour using a quote from one of the meetings: “The more we educate young people, the greater the hope for a world without nuclear weapons.”

She stressed that the primary goal was to reach young people who could spread the message and educate others. Equally important was understanding the needs and desires of the people affected by nuclear testing in Kazakhstan and bringing their voices to an international level. https://astanatimes.com/2024/07/young-changemakers-advocate-for-nuclear-free-future-through-educational-journey-in-kazakhstan/

China’s Low-Cost Nuclear Offer Faces Scrutiny in Kazakhstan

By Eurasianet – Dec 27, 2023,

- The Chinese proposal offers a nuclear plant at half the price of French, Russian, and South Korean alternatives.

- Concerns arise over the Chinese design using outdated technology, despite compatibility with Kazakh-produced fuel assemblies.

- The projected cost for a two-unit nuclear power plant is over $12 billion, with an output of 2.4 GW of power.

A Kazakh media outlet, citing a watchdog group representative, is reporting that the Kazakh government is balking at a Chinese proposal to build the Central Asian nation’s first nuclear power plant. The Kazakh government has not officially commented on the report. ………….. https://oilprice.com/Alternative-Energy/Nuclear-Power/Chinas-Low-Cost-Nuclear-Offer-Faces-Scrutiny-in-Kazakhstan.html

Kazakhstan: Government does hard sell on nuclear, but public remains wary.

It also remains to be worked out how the authorities intend to fund a project that could end up costing $12 billion.

eurasia.net Almaz Kumenov Oct 23, 2023

The authorities in Kazakhstan have for many years been toying with the idea of building a nuclear power plant, but they have lacked the nerve to take a decision in the face of strong public opposition.

In September, President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev opted to punt his way out of the predicament by announcing a referendum on the question.

While Tokayev is evidently in favor of nuclear power, he is eager not to be seen as acting in defiance of broader sentiment………………………………………………………………………………………..

History makes the nuclear issue particularly emotive in Kazakhstan.

For four decades, the Soviet Union used the remote expanses of the northern Kazakh SSR as a testing site for its nuclear bombs. The consequences are detailed in stark terms by Togzhan Kassenova in her 2022 book Atomic Steppe.

“Following a nuclear explosion, radioactive particles mix with dust in the air and spread into the atmosphere. In unfavorable weather, this radioactive dust sweeps up into the clouds and rain, traveling far beyond the test site. The radioactive fallout from the Polygon contaminated not only grazing lands but also water wells, soil, and vegetation. Animals fed on contaminated pastures, and people who lived in the vicinity of the Polygon drank polluted water and milk and ate meat laced with radioisotopes,” Kassenova wrote.

More recently, incidents like the colossal explosion of an arms depot in the southern town of Arys in 2019 have fueled perceptions that safety standards are often flouted by the same people who are supposed to uphold them.

Madina Kuketayeva, coordinator of Anti-NPP, a public association created to resist the plant’s construction, cites corruption as the reason officials would be unable to categorically assure high safety levels.

“But even accident-free operation of the nuclear power plant would cause irreparable damage to the ecology of Lake Balkhash, lead to its drying out, and also harm the health of local residents,” Kuketayeva told Eurasianet.

Geopolitics is a factor too.

Kazakh opponents of the plant and Russia’s war in Ukraine look with alarm at what has happened at the Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant, which is controlled by invading Russian forces. In July, the International Atomic Energy Agency expressed its profound concern over how Russian forces had installed anti-personnel mines around the plant just as Ukrainian troops were embarking on a counteroffensive to recapture lost territory………………………

Some objections to the nuclear power plant are more narrowly technical. Aset Nauryzbayev, an economist who formerly ran state power grid operator KEGOC, says he believes that Kazakhstan is able to build the needed number of renewable energy generators by 2030. Nuclear power is outdated and overly expensive, he argued.

“The maintenance of a nuclear power plant, if it is built, will cost $1.5 billion a year, and we ordinary citizens will pay this unreasonably high price to the future owners of the nuclear power plant,” Nauryzbayev told Eurasianet.

The construction of the nuclear power plant itself will also require huge investments – anywhere up to $12 billion by some reckoning. The source of that funding has not yet been publicly discussed……. https://eurasianet.org/kazakhstan-government-does-hard-sell-on-nuclear-but-public-remains-wary #nuclear #antinuclear #nuclearfree #NoNukes

Kazakhstan’s 40-Year History of Nuclear Testing: Call to Action for Nonproliferation Education

Nuclear tests were carried out there in complete secrecy and absolute denial of harmful effects of the radiation fallout.”

Nearly 1.5 million Kazakh people have suffered as a result of the 456 nuclear tests (340 underground and 116 aboveground) conducted for more than four decades at the Semipalatinsk polygon.

BY ASSEM ASSANIYAZ 28 AUGUST 2023

LONDON – Fourteen years ago, the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA) declared Aug. 29 the International Day against Nuclear Tests. Initiated by Kazakhstan, its increasing relevance for the entire world community is fueled by sprawling geopolitical instability. In an interview with The Astana Times, Margarita Kalinina-Pohl, a U.S.-based expert in nuclear and radiological security, addressed ongoing challenges in nuclear disarmament and raised an importance of nonproliferation education.

Kalinina-Pohl is the director of the CBRN (Chemical, Biological, Radiological and Nuclear) Security Program at the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies (CNS) with a 25-year work experience in education. The center is part of the Middlebury Institute of International Studies (MIIS) at Monterey, California. For this story, she shared intriguing insights of her research on nuclear and radiological security in Central Asia.

The legacy of nuclear testing

Christopher Nolan’s recently released film “Oppenheimer” about the creation of the atomic bomb during World War II remains a topic of heated discussions. However, the Hollywood movie, in her opinion, was “focused on the Trinity Test [the first detonation of the U.S. nuclear weapon] and its successful outcome, but it was silent about the human cost of local communities, known as the New Mexico ‘downwinders’.”

The Trinity nuclear test was part of the U.S.-led Manhattan Project, the code name for the scientific and military undertaking for the development of the first atomic bombs.

“Manhattan Project leaders did not inform people living nearby or downwind about the test, nor were Marshallese informed why they had to move from their land when nuclear atmospheric tests were conducted in the Pacific Ocean,” she said.

“The Soviets did the same to the Kazakh people living in the vicinity of the Semipalatinsk Test Site (STS),” she noted. “Nuclear tests were carried out there in complete secrecy and absolute denial of harmful effects of the radiation fallout.”

Nearly 1.5 million Kazakh people have suffered as a result of the 456 nuclear tests (340 underground and 116 aboveground) conducted for more than four decades at the Semipalatinsk polygon.

In the early 1990s, Kazakhstan faced an urgent need to secure dangerous materials, prevent brain drain, and start remediation and cleanup activities of the weapons of mass destruction (WMD). After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the country transferred nearly 1,400 Soviet nuclear warheads to Russia and joined the nonproliferation regime.

Kalinina-Pohl visited the Semipalatinsk polygon twice during her management activities at the CNS regional office in Kazakhstan. On her first private visit in 1999, she and her colleague from Switzerland had a tour to the experimental field (the former site for atmospheric nuclear tests) and to Degelen mountain (the tunnels for underground tests).

As for the second visit in 2001, she participated in a range of events commemorating the 10th anniversary of the STS closure organized by veterans of the Nevada-Semipalatinsk antinuclear movement, the first major anti-nuclear protest movement in the former Soviet Union. The official ceremony was held in the Kazakh city of Kurchatov and the program included another trip to the site.

“The encounters in Kurchatov and Semipalatinsk had a profound effect on me personally and professionally. It was an eye-opening experience that helped me realize the colossal efforts put into the tests and their large-scale impact on people and environment,” she said.

Another memory she shared from her visits was the impression from the Stronger Than Death monument, a memorial to the victims of nuclear tests. A mother under the nuclear mushroom shielding her child “depicts a powerful image.”

“In addition to dangerous nuclear materials at this site, the Soviet legacy left radioactive sources for military, research, and industrial purposes. On top of that, biological weapons were also produced in Kazakhstan. They were tested at Vozrozhdeniye Island in the Aral Sea,” she noted.

“The voices of the victims were silent for so long,” said Kalinina-Pohl. She emphasized that their true stories are being uncovered today, citing the example of works of a Kazakh artist and a nuclear disarmament activist Karipbek Kuyukov, who experienced firsthand consequences of nuclear tests at STS.

The book “Atomic Steppe: How Kazakhstan Gave Up the Bomb” written by a Kazakh prominent nuclear non-proliferation expert Togzhan Kassenova allowed Kalinina-Pohl to learn more about the plight of victims of nuclear tests in Kazakhstan. She recommended reading it, as “a full understanding of the complexity and soreness of the decision to close the test site came after this story.”

Nuclear and radiological security in Central Asia

This September marks another milestone in the history of nuclear disarmament – the 30th anniversary of the initiative to establish the Central Asian Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone (CANWFZ). It led to the signing of the Treaty on a Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone in Central Asia (Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan) in 2006 in the Kazakh city of Semei, also referred as the Treaty of Semipalatinsk.

Kalinina-Pohl herself was born near one of the former uranium mine sites in Kyrgyzstan.

“Central Asian states – Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan in particular – are still coping with the Soviet uranium mining legacy in the form of impoundments containing radioactive waste, known as tailings. They cause harm to people and the environment, representing a safety concern,” she said.

Along with other countries in the world, Central Asian states are also embarking on civilian nuclear energy programs…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

Kazakhstan’s longstanding commitment to nuclear disarmament resulted in its active participation in drafting and adoption of the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW). It was entered into force in an expedited manner in January 2021. The country’s chairmanship in TPNW by the end of this year will be mainly focused on victim assistance and environmental remediation. https://astanatimes.com/2023/08/kazakhstans-40-year-history-of-nuclear-testing-call-to-action-for-nonproliferation-education/

‘Peaceful Atom’ Sparks Fierce Debate In Kazakh Village Slated To Host Nuclear Power Plant

By Petr Trotsenko, August 28, 2023 Radio Free Europe

ULKEN, Kazakhstan — Plans are under way to build a nuclear power plant (NPP) scheduled to be online by 2035, to supply Kazakhstan’s soaring energy needs.

In Ulken, where the plant is likely to be built, opinions among the village’s 1,500 residents on what a nuclear future for their impoverished lakeside village would look like are split.

Ulken is located 330 kilometers northwest of Almaty on the shores of Lake Balkhash. The village was created in the 1980s to house workers for a planned hydroelectric power plant. That project was unfinished when the Soviet Union collapsed and high-rise apartments are the only completed constructions from the period.

Officially, Ulken is a village, but it feels like an urban settlement. There are no houses here, only apartments. There is no livestock, and no gardens grow in the rocky soil…………………………………………………………………………….

Khairulina wants to increase the population of Ulken, renovate the village, and give life to the abandoned apartments. For these reasons she supports the construction of an NPP. “If the project starts, civilization will come,” she said. The villager is concerned for the environment, but said, “We are not afraid of environmental problems, now everything is made with modern technology.”

Fishermen in Ulken are largely against the NPP project because they fear that Lake Balkhash will be affected and that fishing there could eventually be banned.

It’s not difficult to find fishermen. In front of one abandoned apartment, fish hang in the breeze.

The owner of the property is a young man named Rinat. The 34-year-old fisherman has devoted half of his life to the profession and works the lake every day. Rinat firmly opposes the construction of an NPP.

“The lake sustains us,” he said. “This year the water level in the Balkhash dropped severely, and the fish population decreased. If an NPP is built, there will be no water left in the lake,” Rinat claimed.

At the grocery store, I met another resident, Aleksei Losev. The 35-year-old moved to Ulken six years ago to live with his future wife. He’s not a fisherman, but does not expect anything good from the construction of the NPP.

“On one hand I support its construction, because new jobs will be created, people will come from abroad, and the village will develop. On the other hand, it’s about ecology,” he said, before referencing a troubled Soviet-era NPP in western Kazakhstan that is currently being decommissioned. “Three kilometers from Aqtau there is the Manghystau NPP. The environmental situation there is bad. Why? Wastewater! Both fish and seals are dying…. It will be the same here,” he said……………………………………………………………………………….

In the small assembly hall of the Ulken high school where the August 21 meeting to discuss the NPP took place, it was standing room only. Environmental activists who had travelled from Almaty for the meeting unfurled posters calling to put a stop to the project as residents chanted, “we support the peaceful atom!”

When the discussion on the planned NPP got under way it was clear that there would be little constructive conversation. The emotions of the crowd boiled over.

“We are against the nuclear power plant, it will destroy Balkhash Lake!” activists shouted.

“You’re not a nuclear specialist, how do you know it will be harmful? You don’t live in Ulken” responded some residents.

“It is not only an Ulken problem, this topic should be discussed by all of Kazakhstan!” the activists countered.

…………………………………………………………………… Another local man hoped to work in the future energy sector.

“We residents have been waiting for this construction for 40 years,” he said. “We started with the construction of the power station, we spent days without heat and electricity, we went through many different events together. Ulken needs this energy, this is the center of Kazakhstan. Our region is seismologically stable! There are 15 nuclear power plants in Japan, which has an earthquake every month. Energy is scarce and very expensive in our country. We all need electricity. We support the peaceful atom!” he said.

People in the hall clapped and someone asked, “What about solar energy?” nobody seemed to hear the question amid chants of “Peaceful atom! Peaceful atom!”

Then environmentalist Svetlana Mogilyuk spoke. Like many others, Svetlana came to Ulken to take part in the discussion.

“Dear residents, we have now listened very carefully to what was said,” Mogilyuk said. “No basic, truthful information was provided to you. In contrast to the claim that nuclear energy is not harmful to health, there are qualified studies showing that nuclear energy is still harmful! Numerous studies also confirm that children who live near nuclear power plants are more likely to develop leukemia, and deaths from cancer increase by 24 percent.”

As she made these claims, her microphone cut off. She continued without it.

“Nuclear power plants are harmful, they are accompanied by radioactive emissions. Citizens! You are now being told a lie! Hearings must be accompanied by basic information! You must understand that apart from the NPP, you have other opportunities, you have the opportunity to develop other types of electricity. They will be no less powerful, no less effective, but safer!”

……………………………………………………………………… many in Kazakhstan feel the construction of an NPP is a done deal for the government and that far more depends on its decision than the prospects for locals of a small village on the banks of the Balkhash. https://www.rferl.org/a/kazakhstan-nuclear-power-plant-debate-construction/32563042.html

The Human Dimension to Kazakhstan’s Plutonium Mountain

April 24, 2023, Sig Hecker https://nonproliferation.org/the-human-dimension-to-kazakhstans-plutonium-mountain/

The following is an excerpt from the Stanley Center for Peace and Security.

As we drove deeper into the Semipalatinsk Nuclear Test Site, we found kilometer-long trenches that were clearly the work of professional thieves using industrial earth-moving equipment, rather than hand-dug trenches made by nomad copper-cable-searching amateurs on camelback. Our Kazakh hosts said they could do nothing to stop these operations. In fact, they weren’t sure they had a legal right to stop them from “prospecting” on the site.

It was the sight of these trenches that urged me to convince the three governments that they must cooperate to prevent the theft of nuclear materials and equipment left behind when the Soviets exited the test site in a hurry as their country collapsed.

When the Soviet Union collapsed in December 1991, the most urgent threat to the rest of the world was no longer the immense nuclear arsenal in the hands of the Russian government but rather the possibility of its nuclear assets—weapons, materials, facilities, and experts—getting out of the hands of the government. As director of the Los Alamos National Laboratory, I helped to initiate the US–Russia lab-to-lab nuclear cooperative program in 1992 to mitigate these nuclear threats.

The trilateral US–Russia–Kazakhstan cooperation began in 1999 to secure fissile materials that were left behind by the Soviets at the Semipalatinsk Nuclear Test Site, which was now in the newly independent country of Kazakhstan. The project was kept in confidence until the presidents of the three countries announced it at the Seoul Nuclear Security Summit in 2012

In Doomed to Cooperate, individuals from the three countries recount their cooperative efforts at Semipalatinsk. Unlike the US–Kazakhstan projects initiated earlier on nuclear test tunnel closures, identifying experiments that left weapons-usable fissile materials (plutonium and highly enriched uranium) at the huge test site—whether in the field, in tunnels, or in containment vessels—required trilateral cooperation. The Russian scientists who conducted these experiments were the only ones who knew what was done and where. It required American nuclear scientists who conducted similar tests in the United States to assess how great a proliferation danger the fissile materials in their current state may constitute. And it required Kazakh scientists and engineers to take measures to remediate the dangers. The project also required the political support of all three countries and the financial support of the American government because it was the only one at the time with the financial means. That support came from the US Cooperative Threat Reduction (or Nunn-Lugar) program.

Continue reading at the Stanley Center for Peace and Security.

Commemorate August 29: International Day against Nuclear Tests

Jerusalem Post, By IVO SLAUS, AUGUST 29, 2022, At the initiative of the Republic of Kazakhstan, the UN declared August 29 as the International Day against Nuclear Tests, universally adopted in 2009. While many of those discussing the possible use of nuclear weapons, including Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD), Tactical Nuclear Weapons, and Nuclear Utilization Target Selection (NUTS), and are modernizing and “improving” their nuclear capacity, most of them know almost nothing about nuclear warfare and its consequences for humankind.

In contrast, the people of Kazakhstan and their leaders have witnessed many nuclear tests carried out at the Semipalatinsk Nuclear Test Site for 40 years (1949-1989). From Pervaya Molniya (first lightning) on August 29, 1949, there were 456 tests at Semipalatinsk, 340 underground, and 116 above ground. Kazakhstan and its 1.5 million citizens have suffered from all the negative consequences of nuclear tests. Early death, lifelong debilitating illnesses, and horrific birth defects, including “jelly babies” – children born without limbs.

With good reason, Kazakhstan signed and ratified the Treaty on Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons and was among the original 50 states party to the treaty. On its independence day, Kazakhstan inherited 1,400 Soviet nuclear warheads, and quickly relinquished them, emphasizing that security is better achieved through disarmament and negotiation.

Kazakhstan also initiated a global moment of silence to honor all victims of nuclear weapons testing – at 11:05 Kazakhstan time on August 29. At 11:05 a.m. the clock shows V, standing for victory.

The elimination of nuclear weapons is truly a victory for humankind. On July 9, 1955, the Russell-Einstein Manifesto, signed by 11 outstanding scientists, was issued stressing, “Here is the problem we present to you, stark, dreadful and inescapable: Shall we put an end to the human race or shall mankind renounce war?… Remember your humanity and forget the rest!”

……………………….. we were never as close to doomsday as we are today. Expressed by the doomsday clock, introduced in 1947 and put at seven minutes to midnight, which symbolizes the human-made catastrophe, the doomsday clock since 2020 is at 100 seconds and most likely will deteriorate. The recent conflicts in Europe and Asia will probably abbreviate it further………………………more https://www.jpost.com/opinion/article-715783

-

Archives

- January 2026 (227)

- December 2025 (358)

- November 2025 (359)

- October 2025 (377)

- September 2025 (258)

- August 2025 (319)

- July 2025 (230)

- June 2025 (348)

- May 2025 (261)

- April 2025 (305)

- March 2025 (319)

- February 2025 (234)

-

Categories

- 1

- 1 NUCLEAR ISSUES

- business and costs

- climate change

- culture and arts

- ENERGY

- environment

- health

- history

- indigenous issues

- Legal

- marketing of nuclear

- media

- opposition to nuclear

- PERSONAL STORIES

- politics

- politics international

- Religion and ethics

- safety

- secrets,lies and civil liberties

- spinbuster

- technology

- Uranium

- wastes

- weapons and war

- Women

- 2 WORLD

- ACTION

- AFRICA

- Atrocities

- AUSTRALIA

- Christina's notes

- Christina's themes

- culture and arts

- Events

- Fuk 2022

- Fuk 2023

- Fukushima 2017

- Fukushima 2018

- fukushima 2019

- Fukushima 2020

- Fukushima 2021

- general

- global warming

- Humour (God we need it)

- Nuclear

- RARE EARTHS

- Reference

- resources – print

- Resources -audiovicual

- Weekly Newsletter

- World

- World Nuclear

- YouTube

-

RSS

Entries RSS

Comments RSS