US campaign puts case for disposal, not reprocessing, of used nuclear fuel

This article, from the the nuclear lobby’s propaganda voice – World Nuclear News – goes on later to push for nuclear reprocessing, anyway.

Reprocessing or not -it’s really becoming clear that new nuclear, and patched-up old nuclear reactors are not clean, safe, or economically viable.

WNN, 12 February 2026

The Nuclear Scaling Initiative’s Scale What Works campaign says that direct disposal of used nuclear fuel in the US is the “safest, most secure and least expensive pathway for the country” as nuclear energy capacity is expanded.

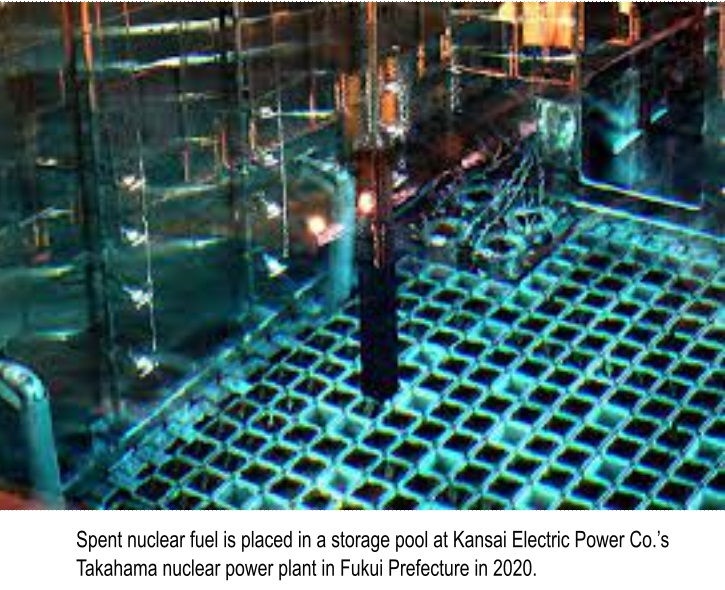

clear, straightforward direct disposal policies’ (Image: Posiva)

The initiative – which is a collaboration of the Clean Air Task Force, the EFI Foundation and the Nuclear Threat Initiative – aims to “build a new nuclear energy ecosystem that can quickly and economically scale to 50+ gigawatts of safe and secure nuclear energy globally per year by the 2030s”.

The Nuclear Scaling Initiative (NSI) Executive Director Steve Comello said: “Making smart fuel management choices today, that acknowledge that reprocessing technologies today are not economically viable and pose security and waste management risks, can drive grid reliability, innovation, and economic and national security for the United States and beyond.”

NSI, whose global advisory board is chaired by former US Secretary of State John Kerry, says that all forms of energy production produces waste, and says that in nuclear’s case, directly storing and “eventually disposing of intact spent fuel” underground “is a safe, straightforward process that uses existing expertise and infrastructure”.

Countries should learn from the reprocessing experience in the UK, Japan and France, NSI says, adding that its view is that reprocessing used fuel is “costly, complex and time-intensive, increasing energy prices for consumers and diverting resources from readily deployable technologies”.

Former Deputy Secretary of Defense and Under Secretary of Energy John Deutch said: “Reprocessing is not a reasonable option: it threatens security, is not cost-effective and will slow our ability to scale nuclear energy.”

Reprocessing of used fuel from commercial reactors has been prohibited in the USA since 1977, with all used fuel being treated as high-level waste………………………………………………………. https://www.world-nuclear-news.org/articles/us-campaign-puts-case-for-disposal-not-reprocessing-of-used-fuel

Why Nuclear Reprocessing?

Does Britain really need nuclear power? – by Ian Fairlea beyondnuclearinternational

“…………………………………………………………………………………………………………..The initial rationale for reprocessing in the 1950s to the 1980s was the Cold War demand for fissile material to make nuclear weapons.

Reprocessing is the name given to the physico-chemical treatment of spent nuclear fuel carried on at Sellafield in Cumbria since the 1950s. This involves the stripping of metal cladding from spent nuclear fuel assemblies, dissolving the inner uranium fuel in boiling concentrated nitric acid, chemically separating out the uranium and plutonium isotopes and storing the remaining dissolved fission products in large storage tanks.

It is a dirty, dangerous, unhealthy, polluting and expensive process which results in workers employed at Sellafield and local people being exposed to high radiation doses.

Terrorism

A major objection to reprocessing is that the plutonium produced has to be carefully guarded in case it is stolen. Four kilos is enough to make a nuclear bomb. Perhaps even more worrying, it does not have to undergo fission to cause havoc: a conventional explosion of a small amount would also cause chaos. A speck of plutonium breathed into the lungs can cause cancer. If plutonium dust were scattered by dynamite, for example, thousands of people could be affected and huge areas might have to be evacuated for decades………….. https://beyondnuclearinternational.org/2025/12/14/does-britain-really-need-nuclear-power/

Is nuclear waste able to be recycled? Would that solve the nuclear waste problem?

Radioactive Wastes from Nuclear Reactors, Questions and Answers, Gordon Edwards 28 July 24.

Well, you know, the very first reactors did not produce electricity. They were built for the express purpose of creating plutonium for atomic bombs. Plutonium is a uranium derivative. It is one of the hundreds of radioactive byproducts created inside every uranium-fuelled reactor. Plutonium is the stuff from which nuclear weapons are made. Every large nuclear warhead in the world’s arsenals uses plutonium as a trigger.

But plutonium can also be used as a nuclear fuel. That first power reactor that started up in 1951 in Idaho, the first electricity-producing reactor, was called the EBR-1 — it actually suffered a partial meltdown. EBR stands for “Experimental Breeder Reactor” and it was cooled, not with water, but with hot liquid sodium metal.

By the way, another sodium-cooled electricity producing reactor was built right here in California, and it also had a partial meltdown. The dream of the nuclear industry was, and still is, to use plutonium as the fuel of the future, replacing uranium. A breeder reactor is one that can “burn” plutonium fuel and simultaneously produce even more plutonium than it uses. Breeder reactors are usually sodium-cooled.

In fact sodium-cooled reactors have failed commercially all over the world, in the US, France, Britain, Germany, and Japan, but it is still the holy grail of the nuclear industry, the breeder reactor, so watch out.

To use plutonium, you have to extract it from the fiercely radioactive used nuclear fuel. This technology of plutonium extraction is called reprocessing. It must be carried out robotically because of the deadly penetrating radiation from the used fuel.

Most reprocessing involves dissolving used nuclear fuel in boiling nitric acid and chemically separating the plutonium from the rest of the radioactive garbage. This creates huge volumes of dangerous liquid wastes that can spontaneously explode (as in Russia in 1957) or corrode and leak into the ground (as has happened in the USA). A single gallon of this liquid high-level waste is enough to ruin an entire city’s water supply.

In 1977, US President Jimmy Carter banned reprocessing in the USA because of fears of proliferation of nuclear weapons at home and abroad. Three years earlier, in 1974, India tested its first atomic bomb using plutonium from a Canadian research reactor given to India as a gift.

The problem with using plutonium as a fuel is that it is then equally available for making bombs. Any well-equipped group of criminals or terrorists can make its own atomic bombs with a sufficient quantity of plutonium – and it only takes about 8 kilograms to do so. Even the crudest design of a nuclear explosive device is enough to devastate the core of any city.

Plutonium is extremely toxic when inhaled. A few milligrams is enough to kill any human within weeks through massive fibrosis of the lungs.

A few micrograms – a thousand times less– can cause fatal lung cancer with almost 100% certainty. So even small quantities of plutonium can be used by terrorists in a so-called “dirty bomb”. That’s a radioactive dispersal device using conventional explosives. Just a few grams of fine plutonium dust could threaten the lives of thousands if released into the ventilation system of a large office building.

So beware of those who talk about “recycling” used nuclear fuel. What they are really talking about is reprocessing – plutonium extraction – which opens a Pandora’s box of possibilities. The liquid waste and other leftovers are even more environmentally threatening, more costly, and more intractable, than the solid waste. Perpetual isolation is still required. ————

Non-proliferation experts urge US to not support nuclear fuel project

By Thomson Reuters, Apr 4, 2024 , By Timothy Gardner, https://wtvbam.com/2024/04/04/non-proliferation-experts-urge-us-to-not-support-nuclear-fuel-project/

WASHINGTON (Reuters) – Nuclear proliferation experts who served under four U.S. presidents told President Joe Biden and his administration on Thursday that a pilot project to recycle spent nuclear fuel would violate U.S. nuclear security policy.

SHINE Technologies and Orano signed a memorandum of understanding in February to develop a U.S. plant to recycle, or reprocess, nuclear waste. It would have a capacity of 100 tonnes a year beginning in the early 2030s.

The project would violate a policy signed by Biden in March, 2023 that says civil nuclear research and development should focus on approaches that “avoid producing and accumulating weapons-usable nuclear material,” the experts said in a letter to the president.

“If such a facility were constructed in the United States, it would legitimize the building of reprocessing plants in other countries, thereby increasing risks of proliferation and nuclear terrorism,” they said.

Many non-proliferation advocates oppose reprocessing, saying its supply chain could be a target for militants seeking to seize materials for use in a crude nuclear bomb.

France and other countries have reprocessed nuclear waste by breaking it down into uranium and plutonium and reusing it to make new reactor fuel. A U.S. supply chain would likely be far longer than in those countries, non-proliferation experts say.

Former President Gerald Ford halted reprocessing in 1976, citing proliferation concerns. Former President Ronald Reagan lifted a moratorium in 1981, but high costs have prevented plants from opening.

The White House’s national security council and the National Nuclear Security Administration did not immediately respond to requests for comment.

A SHINE spokesperson said its technology improves global safety and that “responsible recycling of spent fuel is the only known way to actually eliminate plutonium that has already been generated in fission reactors.”

An Orano USA spokesperson said: “It’s a blending of our expertise to develop a process that is sensitive and addresses non-proliferation concerns, but also gleans this viable commercial material.”

The letter was signed by 11 former U.S. officials including Thomas Countryman, who served under President Barack Obama, Robert Einhorn, who served under President Bill Clinton, Robert Galluci, who served under President George H.W. Bush, and Jessica Matthews, who served under former President Jimmy Carter.

The Biden administration believes nuclear energy to be critical in the fight against climate change. But the waste is kept in storage in pools and then thick casks at nuclear plants across the country as there is no permanent place to put it. The Advanced Research Projects Agency-Energy, or ARPA-E, said in 2022, it is funding a dozen projects to reprocess the waste, with $38 million

The $97 billion mess – spent nuclear fuel reprocessing in Japan

The reprocessing plant was initially scheduled for completion in 1997.

Including expenditures for the future decommissioning of the plant, the total budget has reached 14.7 trillion yen. (close to $97 billion)

Even if the reprocessing plant is completed, it can treat only 800 tons of spent nuclear fuel annually at full capacity, compared with 19,250 tons of spent fuel stored nationwide.

“They have invested too much money in the program to give up on it halfway,“

Another delay feared at nuclear fuel reprocessing plant in Aomori

By AKI FUKUYAMA/ Staff Writer, April 1, 2024, https://www.asahi.com/ajw/articles/15183716

Long-flustered nuclear fuel cycle officials fear there could be another delay in the project.

In a surprise to hardly anyone, the “hopeful outlook” for completion in June of a spent fuel reprocessing plant, a key component in Japan’s nuclear fuel cycle project, was pushed back in late January.

The facility is supposed to extract plutonium and uranium from used nuclear fuel. The recycled fuel can then be used to create mixed-oxide (MOX) fuel, which can run certain nuclear reactors.

But the incompletion of the plant has left Japan with 19,000 tons of spent nuclear fuel with nowhere to go.

The nuclear waste stockpile will only grow, as the administration of Prime Minister Fumio Kishida is turning to nuclear energy to cut Japan’s greenhouse gas emissions and reduce the country’s dependence on increasingly expensive fossil fuels.

Under the plan, 25 to 28 reactors will be running by 2030, more than double the current figure. Tokyo Electric Power Co. is seeking to restart reactors at its Kashiwazaki-Kariwa nuclear power plant in Niigata Prefecture this year.

31 YEARS AND COUNTING

A sign reading “village of energy” stands near Japan Nuclear Fuel Ltd.’s nuclear fuel reprocessing plant in Rokkasho, Aomori Prefecture.

The site, which is 159 times the size of Tokyo Dome, is lined with white buildings with no windows.

Construction started 31 years ago. It was still being built in late November last year, when it was shown to reporters.

The reprocessing plant is located on the Shimokita Peninsula at the northern tip of the main Honshu island.

Crops in the area are often damaged by cold humid winds during summer, so Rokkasho village accepted the plant in 1985 for local revitalization in place of agriculture.

Employees of privately-run Japan Nuclear Fuel, which is affiliated with nine major power companies, and other industry-related personnel account for more than 10 percent of Rokkasho’s population.

After repeated readjustments to the schedule, Naohiro Masuda, president of Japan Nuclear Fuel, said in December 2022 that the plant’s completion should come as early as possible during the first half of fiscal 2024, which is April to September 2024. More specifically, he pointed to “around June 2024.”

But at a news conference on Jan. 31 this year, Masuda said it is “inappropriate to keep saying the plant will be completed in June.”

The reprocessing plant was initially scheduled for completion in 1997.

Many insiders at the plant say it will be “quite difficult” to complete the work within the first half of fiscal 2024.

If officially decided, it will be the 27th postponement of the completion.

PROLONGED SCREENING, ACCIDENTS

One of the reasons for the delay of the completion is prolonged screenings by the Nuclear Regulation Authority.

Flaws were identified one after another in the company’s documents submitted to the nuclear watchdog, and around 400 Japan Nuclear Fuel employees are working on the papers within a gymnasium at the plant site.

Mechanical problems have also hampered progress. In 2022, for example, a system to cool high-level radioactive liquid waste broke down.

Masuda visited industry minister Ken Saito on Jan. 19 to report on the situation at the plant.

Saito told Masuda about the construction, “I expect you to forge ahead at full tilt.”

Masuda stressed his company “is fully devoted to finishing construction as soon as possible,” but said safety “screening is taking so much time because we have myriad devices.”

The cost to build the reprocessing plant, including new safety measures, has ballooned to 3.1 trillion yen ($20.57 billion), compared with the initial estimate of 760 billion yen.

Including expenditures for the future decommissioning of the plant, the total budget has reached 14.7 trillion yen. (close to $97 billion)

Even if the reprocessing plant is completed, it can treat only 800 tons of spent nuclear fuel annually at full capacity, compared with 19,250 tons of spent fuel stored nationwide.

Kyushu Electric Power Co. said in January that it would tentatively suspend pluthermal power generation at the No. 3 reactor of its Genkai nuclear power plant in Saga Prefecture. The reactor uses MOX fuel.

Kyushu Electric commissioned a French company to handle used fuel, but it recently ran out of stocks of MOX fuel.

Kyushu Electric has a stockpile of plutonium in Britain, but it cannot take advantage of it because a local MOX production plant shut down.

HUGE INVESTMENT

Calls have grown over the years to abandon the nuclear fuel cycle project.

Many insiders of leading power companies doubt whether the reprocessing plant “will really be completed” at some point.

But the government has maintained the nuclear fuel cycle policy, despite the huge amounts of time and funds poured into it.

“The policy is retained just because it is driven by the state,” a utility executive said.

Hajime Matsukubo, secretary-general of nonprofit organization Citizens’ Nuclear Information Center, said the government’s huge investment explains why the fuel cycle program has yet to be abandoned.

“They have invested too much money in the program to give up on it halfway,” Matsukubo said.

La Hague reprocessing plant: expansion and continued operation until at least 2100

Last week, the Élysée Palace confirmed that the French reprocessing

plant at La Hague is to be expanded. Extensive investments are planned in

this context. There have already been plans since 2020 to build another

storage pool on the plant site.

At La Hague, there is still radioactive

waste from Germany, which may be returned this year. It was actually just a

side note: The Conseil de Politique Nucléaire (Nuclear Policy Council),

which was founded in 2023 and met at the Elysée Palace last Monday,

confirmed the prospect of major investments at La Hague in order to extend

the lifespan of the facilities until at least 2100.

Corresponding press

reports were confirmed by the Elysée Palace on Tuesday: The Council had

“confirmed the major guidelines of French policy on the nuclear fuel cycle,

which combines reprocessing, reuse of spent fuel and closing the cycle”,

the La Hague site would “be the subject of major investment”. No specific

timetables or amounts were mentioned in this context.

GRS 12th March 2024

Nuclear industry wants Canada to lift ban on reprocessing plutonium, despite proliferation risks

The CANDU Owners Group is far from neutral or independent…………… First, Canadian Nuclear Laboratories is a private company owned by a consortium of multi-national companies: AtkinsRéalis (formerly SNC Lavalin), Fluor, and Jacobs. ……...has overseas members, including utilities from China, Pakistan, India, South Korea, Argentina, and Romania. The first three countries are nuclear weapons states that either possess reprocessing plants for military purposes (India and Pakistan) or reportedly divert plutonium extracted from commercial spent fuel for military purposes (China), while South Korea and Argentina have for decades flirted with the idea of reprocessing.

Bulletin, By Gordon Edwards, Susan O’Donnell | March 11, 2024

Plutonium is “the stuff out of which atomic bombs are made.” Plutonium can also be used as a nuclear fuel. Reprocessing is any technology that extracts plutonium from used nuclear fuel. In Canada, the nuclear industry seems determined to close the nuclear fuel cycle by pushing for a policy to permit reprocessing—thereby seeking to lift a 45-year-old ban.

In 1977, Canada tacitly banned commercial reprocessing of used nuclear fuel, following the lead of the Carter administration, which explicitly opposed reprocessing because of the possibility it could lead to increased proliferation of nuclear weapons around the world.[1] That unwritten policy in Canada has held sway ever since.[2] New documents obtained through Canada’s Access to Information Act reveal that, behind closed doors, the nuclear industry has been crafting a policy framework that, if adopted, would overturn the ban and legitimize the extraction of plutonium from Canada’s used commercial nuclear fuel.

For over two years, documents show that the Canadian government has held a series of private meetings with industry representatives on this subject, keeping such activities secret from the public and from parliament. This raises questions about the extent to which nuclear promoters may be unduly influencing public policymaking on such sensitive nuclear issues as reprocessing in Canada.[3] But, given the stakes for the whole society and even the entire planet, the public must have a say about nuclear policy decisions…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

Before the ban. Dreams of a plutonium-fueled economy were spawned in 1943-44 by British, French, and Canadian scientists working at a secret wartime laboratory in Montreal, which was part of the Anglo-American Project to build the first atomic bombs. Canada’s first heavy-water reactors were designed by the Montreal team, in part, to produce plutonium for weapons. The team also had hopes that after the war, plutonium might become a dream fuel for the future. They envisioned a “breeder reactor” that could produce more plutonium than it uses, thereby extending nuclear fuel supplies.

For 20 years after the war, Canada sold uranium and plutonium for US bombs. Two reprocessing plants were operated at Chalk River Nuclear Laboratories in Ontario. In addition, all the pilot work on plutonium separation needed to design Britain’s Windscale reprocessing plant was carried out at Chalk River.

After the ban. Although the 1977 ban scuppered AECL’s hopes for commercial reprocessing, plutonium remained the holy grail. In the decades that followed, AECL researchers studying the geologic disposal of high-level radioactive waste clandestinely carried out reprocessing experiments at the Whiteshell Nuclear Research Establishment in Manitoba. Instead of burying used nuclear fuel bundles, the scientists anticipated burying solidified post-reprocessing waste. Meanwhile, AECL scientists at Chalk River fabricated three tonnes of mixed-oxide fuel (MOX) in glove boxes, using plutonium obtained from CANDU fuel reprocessed overseas. In 1996, Prime Minister Jean Chrétien volunteered to import weapons-grade plutonium from dismantled US and Soviet warheads to fuel CANDU reactors. Facing fierce public opposition in Canada, the project never came to pass.

But the dream of a plutonium economy remained. In 2011, a sprawling mural on three walls of the Saskatoon Airport depicted the nuclear fuel chain, from mining uranium to the reprocessing of used fuel to recover “potential energy” before disposing of the leftovers. Although the word plutonium appeared nowhere, reprocessing was presented as the inevitable final step in this vision of a virtuous nuclear fuel cycle. The mural was commissioned by Cameco, the giant Canadian multi-national corporation that helped make the central Canadian province of Saskatchewan into the “Saudi Arabia of uranium.” At the time, Cameco co-owned the largest operating nuclear power station in the world, the eight-reactor Bruce complex beside Lake Huron bordering the United States.

Despite such hopes, it became fashionable to publicly downplay reprocessing as expensive and therefore economically unlikely.[5] But the technology stayed on the books as a possibility, especially in case future generations would want to extract plutonium from used nuclear fuel for re-use before disposing of the remaining radioactive waste.

Back to the future? New Brunswick has one 660-megawatt-electric CANDU reactor at Point Lepreau on the Bay of Fundy in eastern Canada. The plant has been operating for over 40 years. In March 2018, two start-up companies—UK-based Moltex Energy and US-based ARC Clean Technology—offered to build “advanced” (fast) reactors on the same site.

The Moltex design is a 300-megawatt-electric molten salt reactor called “Stable Salt Wasteburner.” It is to be fueled with plutonium and other transuranic elements extracted from CANDU used fuel already stored on that site. Accordingly, the Moltex proposal requires a reprocessing plant in tandem with the reactor. The ARC design is a 100-megawatt-electric liquid sodium-cooled reactor, inspired by the second Experimental Breeder Reactor (EBR-2) operated by the Argonne National Laboratory in Idaho between 1964 and 1994. Although the ARC-100 does not require reprocessing at the outset, its optimal performance requires that the used fuel be recycled, likely through reprocessing.

From the beginning, Moltex claimed its proposed molten salt reactor would “recycle” CANDU used fuel and “burn” it in its molten salt reactor. Moltex claims that this would virtually eliminate the need for a deep geologic repository by turning a million-year disposal problem into a roughly 300-year storage problem. This claim has been flatly rebuffed.[6] Only later did the public learn that the Moltex technology requires reprocessing CANDU used fuel to extract plutonium using an innovative process called “pyroprocessing.” (In pyroprocessing, used fuel is converted to a metal and immersed in molten salt, then the plutonium and other transuranic elements are recovered by passing a current through the salt and collecting the desired products on electrodes.)

ARC Clean Technology maintains that its reactor design is proven by the 30-year operating experience of the EBR-2 reactor, despite differences in size and fuel enrichment.[7] The company, however, says nothing about the intimate connection between breeder reactors and plutonium, nor does it mention the chequered history of liquid sodium-cooled reactors globally—including the Fermi Unit 1 reactor’s partial meltdown near Detroit, the commercial failure of France’s Superphénix, the conversion of a German breeder reactor into an amusement park, or the dismal performance of Japan’s Monju reactor.

For either of the proposed New Brunswick reactors to operate as intended, Canada would need to lift its 45-year-old ban on commercial reprocessing of used nuclear fuel.

Testing the limits. The first sign that Canada’s reprocessing ban might be lifted came in 2019, when the federal government’s Impact Assessment Act exempted specified projects from environmental assessment. The exemption included any reprocessing plant with a production capacity of up to 100 metric tons (of used nuclear fuel) annually—just above the reprocessing capacity required for the Moltex project.[8]

Public calls to explicitly ban reprocessing started shortly after March 2021, when the federal government gave 50.5 million Canadian dollars in funding for Moltex’s project. This project clearly requires reprocessing: Without the plutonium produced by CANDU reactors to fuel its proposed molten salt reactor, the Moltex project can go nowhere.

In addition, Moltex hopes to eventually export the technology or the fuel, or both. Many Canadians are alarmed at the prospect of normalizing the use of recycled plutonium as a nuclear fuel in Canada and abroad.

In 2021, in response to a recommendation by the International Atomic Energy Agency, the Canadian government conducted public consultations to develop a modernized policy on commercial radioactive waste management and decommissioning. Over 100 citizens groups participated, and many called for an explicit ban on reprocessing.

Public attention to the issue of reprocessing grew after nine US nonproliferation experts sent an open letter to Prime Minister Justin Trudeau in May 2021. The letter expressed concern that by funding a spent fuel reprocessing and plutonium extraction project, Canada would “undermine the global nuclear weapons nonproliferation regime that Canada has done so much to strengthen.” …………………..

A second letter sent to Trudeau in July 2021 refuted “misleading claims” that Moltex posted on-line in rebuttal to the first letter. Moltex’s rebuttal claims were quickly taken down. And a third letter authored by one of the US nonproliferation experts was sent in November 2021. None of the government responses to these three letters addressed the core issue, which is the request for an independent review of the proliferation implications of Canada’s funding of reprocessing.

The federal government released its draft policy for radioactive waste management and decommissioning in March 2022, hinting that reprocessing might be permitted in the future. Public interest groups made their opposition to that suggestion very clear. A national steering group coordinated by Nuclear Waste Watch, a Canada-based network of public interest organizations, released an alternative policy proposal that explicitly banned reprocessing. The Council of Canadians, a national advocacy group, sent out an action alert that generated 7,400 letters calling for the explicit prohibition of reprocessing.

The Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission, tasked with the job of licensing Moltex’s proposed reactor, declared that a policy framework for reprocessing is necessary and that such a policy must come from the federal government.[9] Moltex’s Chief Executive Officer, Rory O’Sullivan, observed that Canada was chosen by Moltex because the country had no explicit policy on reprocessing: “Moltex would likely not have come to Canada if a reprocessing policy had been mandated at the time.”

In November 2021, Canada’s Ministry of Natural Resources—the lead federal department on nuclear issues—issued an internal memo entitled “Policy Development on Reprocessing” that refers to a series of planned meetings on reprocessing with industry representatives starting December 1, 2021.[10] The CANDU Owners Group—a nonprofit corporation assembling utilities operating CANDU reactors, Canadian Nuclear Laboratories, and nuclear suppliers—was singled out by the ministry to prepare a policy paper on reprocessing.[11]

The CANDU Owners Group is far from neutral or independent.

First, Canadian Nuclear Laboratories is a private company owned by a consortium of multi-national companies: AtkinsRéalis (formerly SNC Lavalin), Fluor, and Jacobs. The company is currently constructing a government-funded facility with hot cells at Chalk River to conduct research, including on reprocessing and plutonium extraction. Canadian Nuclear Laboratories operates under a “government-owned contractor operated” agreement with Atomic Energy of Canada Limited, the same publicly owned corporation that pushed for commercial reprocessing in the late 1970s.

The CANDU Owners Group also has overseas members, including utilities from China, Pakistan, India, South Korea, Argentina, and Romania. The first three countries are nuclear weapons states that either possess reprocessing plants for military purposes (India and Pakistan) or reportedly divert plutonium extracted from commercial spent fuel for military purposes (China), while South Korea and Argentina have for decades flirted with the idea of reprocessing.

By all evidence, the government of Canada is currently enlisting private entities that favor reprocessing to assist in the development of an industry-friendly policy on reprocessing. And the government does this without involving the public, parliament, or outside experts—all of whom have expressed a keen interest—and repeatedly asked to participate—in plutonium policy discussions. In the process, misleading information about reprocessing is being forwarded to government officials with no other voices to correct the record.[12]

In the most recent move, a dozen US nonproliferation experts wrote again to Prime Minister Trudeau on September 22, 2023, after the release of documents obtained through an access to information request. In their letter, the experts reiterated their concerns that the Canadian government is funding a project that would lead to increase the availability—and therefore potential proliferation—of weapons-usable plutonium for civilian purposes in Canada and beyond.

Democratic deficit. Despite all these developments, there has been no public discussion or parliamentary deliberation about the implications of introducing civilian reprocessing into Canada’s nuclear fuel cycle. Absence of transparency and public debate means the democratic process is being ignored. Yet, the issue is of great public importance because of the taxpayer money invested, proliferation risks involved, and the long-term societal implications of the security measures needed to safeguard nuclear weapons usable materials.

This makes one wonder why it took a group of concerned citizens and an access to information request to find out that, behind closed doors, the nuclear industry has been drafting its own policy to permit commercial reprocessing, expecting its adoption by the government of Canada against all objective criteria of democracy.

n 1976, British nuclear physicist Brian Flowers authored a Royal Commission report to the UK parliament. He wrote: “We regard the future implications of a plutonium economy as so serious that we should not wish to become committed to this course unless it is clear that the issues have been fully appreciated and weighed; in view of their nature we believe this can be assured only in the light of wide public understanding.”

The same precept should apply to nuclear policy in today’s Canada.

Notes…………………………………………………………………. https://thebulletin.org/2024/03/nuclear-industry-wants-canada-to-lift-ban-on-reprocessing-plutonium-despite-proliferation-risks/

U.S. Congress about to fund revival of nuclear waste recycling to be led by private start-ups.

Jimmy Carter Killed This Technology 50 Years Ago. Congress Is About To

Fund Its Revival. The spending bill the House just passed contains $10

million for recycling nuclear waste. The nuclear waste sitting at power

plants across the United States contains enough energy to power the country

for more than 100 years.

But recycling spent uranium fuel was banned in

1977 because President Jimmy Carter feared that nuclear reprocessing could

lead to more production of atomic weapons. In the last 47 years, China,

France, Japan, Russia and the United Kingdom have all developed the tools

to recycle nuclear waste.

The U.S., by contrast, made a plan to bury that

spent fuel underground and even built a facility — but then abandoned the

strategy without any clear alternative. The short-term spending bill passed

this week in the U.S. House to avert a government shutdown contains the

first major funding for commercializing technology to recycle nuclear

waste. The legislation earmarks $10 million for a cost-sharing program to

help private nuclear startups pay for the expensive federal licensing

process ― and for the first time explicitly makes waste-recycling

companies eligible.

Huffington Post 8th March 2024

Rokkasho redux: Japan’s never-ending nuclear reprocessing saga

By Tatsujiro Suzuki | December 26, 2023, https://thebulletin.org/2023/12/rokkasho-redux-japans-never-ending-reprocessing-saga/

The policy seeks to at least begin to deal with the huge stocks of plutonium Japan has amassed

According to a recent Reuters report, Japan Nuclear Fuel Ltd (JNFL) still hopes to finish construction of Japan’s long-delayed Rokkasho reprocessing plant in the first half of the 2024 fiscal year (i.e. during April-September 2024). The plant—which would reprocess spent nuclear fuel from existing power plants, separating plutonium for use as reactor fuel—is already more than 25 years behind schedule, and there are reasons to believe that this new announcement is just another wishful plan that will end with another postponement.

One indication of further possible delays: On September 28, 2023, Naohiro Masuda, president of JNFL, stated that the safety review of the reprocessing plant by Japan’s Nuclear Regulation Authority will be difficult to complete by the end of 2023. He nevertheless insisted that the company could still meet completion target date in 2024.

Here is a partial history of past key developments that make completion in 2024 seem unlikely:

1993: Construction starts.

1997: Initial target for completion.

2006-2008: Hot tests conducted, revealing technical problems with the vitrification process for dealing with waste produced during reprocessing.

2011: Fukushima Dai-ichi nuclear plant accident.

2012: New safety regulation standards introduced.

2022: Completion target date postponed to June 2024)

The 2022 postponement was the 26th of the Rokkasho project.

Why so many postponements? There seem to be at least five underlying reasons for the postponements for the Rokkasho plant. First, JNFL lacks relevant expertise to manage such a technologically complex and hazardous project, which is owned by nine nuclear utilities plus all other major companies associated with nuclear power in Japan. Most of the firm’s senior executives are from shareholding companies (especially utility companies) and are not necessarily experts in the field of reprocessing spent nuclear fuel.

Second, the technologies in the plant came from different companies and institutions. The management of the project is therefore technically complex.

Third, the post-Fukushima-accident nuclear facility safety licensing review process is much more stringent than what existed before the accident. For example, the Nuclear Regulation Authority told JNFL at their November 25, 2023 meeting: “JNFL should immediately make improvements because it is clear that JNFL does not understand the contents of the permit well enough to confirm the adequacy of the design of the facilities on site and has not visited the site.”

Fourth, the financial costs to JNFL of postponement are covered by the utilities’ customers, because the utilities must pay a “reprocessing fee” every year, based on the spent fuel generated during that year, whether or not the reprocessing plant operates. The system by which the Nuclear Reprocessing Organization of Japan decides the reprocessing fee is not transparent.

Fifth, the project lacks independent oversight. Even though JNFL’s estimate of the cost of building and operating the Rokkasho plant has increased several-fold, no independent analysis has been done by a third party. One reason is that some of the shareholders are themselves contractors working on the plant and have no incentive to scrutinize the reasons for the cost increases or the indefinite extension of the construction project.

After so many postponements, there is reason to wonder whether the plant will ever operate, but the government and utilities continue to insist that the plant will open soon. Even if Rokkasho were to operate, it may suffer from the same kinds of problems that marked Britain’s light-water reactor spent fuel reprocessing experience, as described in Endless Trouble: Britain’s Thermal Oxide Reprocessing Plant (THORP).

Why does Japan’s commitment to reprocessing continue?

Despite the serious and longstanding problems the Rokkasho plant has faced (and continues to face), Japanese regulators and nuclear operators have doggedly pursued the project. There are four reasons:

Spent fuel management. Currently, most of Japan’s spent nuclear fuel is stored in nuclear power plant cooling pools. But the pool capacities are limited, and the 3,000-ton-capacity Rokkasho spent fuel pool is also almost full. The nuclear utilities must therefore start operating the Rokkasho plant unless they can create additional spent fuel storage capacity, either on- or off-site. The Mutsu spent fuel storage facility is a candidate for additional capacity, but due to the concern that spent fuel could stay there forever, Mutsu city refuses to accept spent fuel unless the Rokkasho reprocessing plant begins to operate. The Rokkasho plant design capacity is 800 tons of spent fuel per year.

Legal and institutional commitments. Under Japan’s nuclear regulations, utilities must specify a “final disposal method” for spent fuel. The law on regulation of nuclear materials and nuclear reactors states that “when applying for reactor licensing, operators must specify the final disposal method of spent fuel” (Article 23.2.8). In addition, there was a clause that “disposal method” should be consistent with implementation of the government policy, which specified reprocessing as the disposal method. Although that clause was deleted in the 2012 revision of the law after the Fukushima accident, the Law on Final Disposal of High-Level Radioactive Waste still bans direct disposal of spent fuel. In addition, the 2016 Law on Reprocessing Fees legally requires utilities to submit reprocessing fees for all spent fuel generated every year since they stated in their applications that “final disposal method” for their spent fuel would be reprocessing.

Commitments to hosting communities. The nuclear utilities committed—albeit tacitly—to the communities hosting nuclear power plants that they would remove the spent fuel to reprocessing plants, since that was the national policy. Separately, JNFL signed an agreement with Rokkasho village and Aomori prefecture that says that if the Rokkasho reprocessing plant faces “severe difficulties,” other measures will be considered—including the return of spent fuel stored at Rokkasho to the nuclear power plants.

Local governments hosting nuclear power plants were not involved in this deal, however. They could therefore just refuse to receive spent fuel from Aomori.

In fact, after the Fukushima accident, when the government was considering amending the nuclear fuel cycle policy to include a “direct disposal option” for spent fuel in a deep underground repository, the Rokkasho village parliament (at the behind the scenes suggestion by the then JNFL president, Yoshihiko Kawai), issued a strong statement asking for “maintenance of the current nuclear fuel cycle policy.”

The statement continued that, if Japan’s fuel cycle policy changed, Rokkasho would: refuse to accept further waste from the reprocessing of Japan’s spent fuel in the UK and France; require the removal of reprocessing waste and spent fuel stored in Rokkasho; no longer accept spent fuel; and seek compensation for the damages caused by the change of the policy.

Institutional and bureaucratic inertia. In Japan, bureaucrats rotate to new positions every two or three years and are reluctant to take the risk of changing existing policies. They therefore tend to stick with past commitments. Institutional inertia becomes stronger as a project becomes bigger. The Rokkasho reprocessing project is one of the largest projects ever in Japan. Changing the project is therefore very difficult.

Will Japan’s new plutonium capping policy have any real impact? In 2018, Japan’s Atomic Energy Commission announced a new policy on “Basic Principles on Utilization of Plutonium” (see also this post). Under the new policy, the commission proposed that Japan would reduce its stockpile of separated plutonium, starting with a commitment not to increase it, and that reprocessing would take place only when a credible plan to use the separated plutonium existed.

The policy seeks to at least begin to deal with the huge stocks of plutonium Japan has amassed, both in European separation facilities (some 36.7 tons) and in Japan (10.5 tons), in anticipation of using the plutonium widely to fuel nuclear reactors—which so far has not materialized. In conjunction with the new Reprocessing Fee Law, the new plutonium policy gives the government legal authority to control the pace of reprocessing.

But it is not clear how the “capping policy” will be implemented. It is not a legally binding document, and no regulation has been introduced to control reprocessing. Utilities must submit specific plans for plutonium use to the Atomic Energy Commission for its review before reprocessing of their fuel begins. But the commission can only give advice to the government about the credibility of these plans, giving rise to questions about whether the policy will lead to sustained changes in reprocessing activity. A similar “paper rule” on plutonium has existed since 2003.

A way out. Japan could extricate itself from its reprocessing and plutonium problems in several ways. All involve significant changes in policy that would:

Find additional spent fuel storage capacity, on- or off-site. Local communities may be more willing to accept on-site dry cask storage of spent fuel if they are told that it is safer than spent fuel pool storage. For example, Saga Prefecture and Genkai-town, which host Kyushu Electric’s Genkai Nuclear Power Plant, have agreed to host dry cask storage starting in 2027. Host communities may want guarantees that spent fuel will be removed after a specified storage period. Such a guarantee could be given by the central government.

Amend the law on final disposal of high-level radioactive waste. An amendment could allow direct disposal of spent nuclear fuel in a deep underground repository. This would provide more flexibility in spent fuel management and make it easier for communities to host interim spent fuel storage.

Amend the Reprocessing Fee Law and shut down Rokkasho. An amendment to the law on reprocessing fees could allow the government to use reprocessing funds to implement a shutdown of the Rokkasho reprocessing plant. Such a plan could include payment of the debt JNFL has incurred while pursuing the Rokkasho project and funds for dry cask interim storage. This would enable the government to finally end the problem-plagued Rokkasho reprocessing plant project.

Ottawa yet to decide whether reprocessing spent nuclear fuel should be allowed in Canada

MATTHEW MCCLEARN, (September 26, 2023)

More than two years after it provided tens of millions of dollars to a company seeking to reprocess spent nuclear fuel, the Canadian government has yet to decide whether the practice should be allowed on Canadian soil.

Reprocessing involves extracting uranium and plutonium from irradiated fuel to make new fuel. In March, 2021, the government provided Moltex Energy with $50.5-million to support development of a reprocessing facility (known as Waste To Stable Salt, or WATSS) and a reactor that would burn fuel it produced. Moltex plans to construct both at New Brunswick Power’s Point Lepreau station, on the northern shore of the Bay of Fundy.

Currently reprocessing is not conducted in Canada. With the notable exception of Japan, it’s done almost exclusively by countries that have nuclear weapons programs. It’s controversial: Critics warn reprocessing increases proliferation risks, and that Canada would set a bad precedent by pursuing it………………………………….

Documents released this summer under the Access to Information Act to Susan O’Donnell, an activist on nuclear issues and researcher at the University of New Brunswick, and provided to The Globe, show that the CANDU Owners Group (which represents utilities such as New Brunswick Power that operate Canadian-designed reactors) drafted a reprocessing policy and distributed it among government and industry officials.

The documents also reveal that Moltex warned the government last year the company would have difficulty raising money until the government clarified that reprocessing will be allowed……………………….https://www.theglobeandmail.com/business/article-moltex-canada-nuclear-waste-trudeau-letter/

Japan’s Rokkasho nuclear reprocessing project delayed again – for the 26th time

The completion of a nuclear fuel reprocessing plant in Aomori Prefecture

will be delayed by two years, the 26th postponement since the project

started three decades ago.

Senior officials with Japan Nuclear Fuel Ltd.,

operator of the facility under construction, said the new completion date

will be in the first half of fiscal 2024. The officials visited the Aomori

prefectural government and the village hall of Rokkasho, the site of the

plant, on Dec. 26 to explain the situation.

An earlier completion timeframe

was listed as in the first half of fiscal 2022. But the company in

September postponed this deadline without giving a new date. It said

prolonged safety checks of the facility by the Nuclear Regulation Authority

made it difficult to do so and pledged to announce the new deadline by the

year-end.

According to Japan Nuclear Fuel’s latest estimate, the NRA’s

screening of the detailed design of the plant will take about a year, while

checks of the plant will take four to seven months after it clears the

safety standards. The company said it will work hard to move up the

completion to an early date of the first half of fiscal 2024.

Asahi Shimbun 27th Dec 2022

Civil society groups urge feds to ban reprocessing used nuclear fuel.

Natasha Bulowski / Local Journalism Initiative / Canada’s National Observer, 30 Dec 22,

Canada’s forthcoming radioactive waste policy should include a ban on plutonium reprocessing, a national alliance of civil society organizations says.

Plutonium — a radioactive, silvery metal used in nuclear weapons and power plants — can be separated from spent nuclear reactor fuel through a process known as “reprocessing” and reused to produce weapons or generate energy.

The federal government is expected to release its policy for managing radioactive waste early next year. On Dec. 15, a handful of organizations urged Ottawa to include a ban on plutonium reprocessing because of its links to nuclear weapons proliferation and environmental contamination.

The World Nuclear Association says reprocessing used fuel to recover uranium and plutonium “avoids the wastage of a valuable resource.”

Ottawa has yet to take a definitive stance on the process. A draft policy released last February said: “Deployment of reprocessing technology … is subject to policy approval by the Government of Canada.”

But in 2021, a New Brunswick company, Moltex Energy, received $50.5 million from the federal coffers to help design and commercialize a molten salt reactor and spent fuel reprocessing facility. Commercial plutonium reprocessing has never been carried out in Canada, and we should not start now, according to Nuclear Waste Watch, a national network of Canadian organizations concerned about high-level radioactive waste and nuclear power. The group is among those pushing for a plutonium reprocessing ban.

More than 7,000 Canadians submitted letters including a demand to ban plutonium reprocessing throughout the consultation process, according to a Nuclear Waste Watch news release.

The group points to a 2016 report by Canadian Nuclear Laboratories stating reprocessing would “increase proliferation risk.”

“There is no legitimate reason to support technologies that create the potential for new countries to separate plutonium and develop nuclear weapons,” Susan O’Donnell, spokesperson for the Coalition for Responsible Energy Development in New Brunswick, said in Nuclear Waste Watch’s news release. “The government should stop supporting this dangerous technology.”

China, India, Japan, Russia, the United Kingdom and some European countries, like France, reprocess their spent nuclear fuel.

Canada’s forthcoming radioactive waste policy should include a ban on plutonium reprocessing, a national alliance of civil society organizations says. Plutonium separated from used nuclear fuel can be reused in power generation or nuclear weapons

Dishonesty: British authorities knew it was wrong to proceed with the thermal oxide reprocessing plant (Thorp) at Sellafield.

Letter William Walker: In 1993, a government official told me that “it

was sometimes right to do the wrong thing”. For reasons of political

expediency, it was right to give political consent for the operation of the

thermal oxide reprocessing plant (Thorp) at Sellafield.

This huge facility, not mentioned in Samanth Subramanian’s fine long read, had been built over

the previous decade to reprocess British and foreign, especially Japanese,

spent nuclear fuels. Abandoning it would be too embarrassing for the many

politicians and their parties that had backed it, expensive in terms of

compensation for broken contracts, and damaging to Britain’s and the

nuclear industry’s international reputation.

It was wrong to proceed, as

the government well knew, because the primary justification for its

construction – supply of plutonium for fast breeder reactors (FBRs) – had

been swept away by the abandonment of FBRs in the 1980s (none were built

anywhere).

Because returning Thorp’s separated plutonium and radwaste to

Japan would be difficult and risky.

Because decommissioning Thorp would

become much more costly after its radioactive contamination.

Because there was a known win-win solution, favoured by most utilities – store the spent

fuel safely at Sellafield prior to its return to senders, avoiding the many

troubles that lay ahead.

Guardian 22nd Dec 2022

France sends reprocessed nuclear fuel to Japan, despite environmental and safety dangers

https://japantoday.com/category/national/france-sends-latest-nuclear-shipment-to-japan CHERBOURG, France 18 Sept 22

Two ships carrying reprocessed nuclear fuel destined for Japan set sail Saturday morning from northern France, an AFP photographer said, despite criticism from environmental campaigners.

The fuel was due to leave the northern French port city of Cherbourg earlier this month but was delayed by the breakdown of loading equipment.

Environmental activists have denounced the practice of transporting such highly radioactive materials, calling it irresponsible.

The previous transport of MOX fuel to Japan in September 2021 drew protests from environmental group Greenpeace.

MOX fuel is a mixture of reprocessed plutonium and uranium.

“The Pacific Heron and Pacific Egret, the specialised ships belonging to British company PNTL, left Cherbourg harbor on September 17. They will ensure the shipment of MOX nuclear fuel to Japan,” French nuclear technology group Orano said in a statement Saturday.

They are bound for Japan for use in a power plant and Orano said it expected the shipment to arrive in November.

Japan lacks facilities to process waste from its own nuclear reactors and sends most of it overseas, particularly to France.

The operation was carried out “successfully”, Orano said, and it is the second shipment that arrived in Cherbourg from a plant in La Hague, located 20 kilometers away, after the first came on September 7.

Yannick Rousselet of Greenpeace France previously denounced the shipment.

“Transporting such dangerous materials from a nuclear proliferation point of view is completely irresponsible,” he said last month.

MOX is composed of 92 percent uranium oxide and eight percent plutonium oxide, according to Orano.

The plutonium “is not the same as that used by the military,” it said.

-

Archives

- February 2026 (211)

- January 2026 (308)

- December 2025 (358)

- November 2025 (359)

- October 2025 (376)

- September 2025 (258)

- August 2025 (319)

- July 2025 (230)

- June 2025 (348)

- May 2025 (261)

- April 2025 (305)

- March 2025 (319)

-

Categories

- 1

- 1 NUCLEAR ISSUES

- business and costs

- climate change

- culture and arts

- ENERGY

- environment

- health

- history

- indigenous issues

- Legal

- marketing of nuclear

- media

- opposition to nuclear

- PERSONAL STORIES

- politics

- politics international

- Religion and ethics

- safety

- secrets,lies and civil liberties

- spinbuster

- technology

- Uranium

- wastes

- weapons and war

- Women

- 2 WORLD

- ACTION

- AFRICA

- Atrocities

- AUSTRALIA

- Christina's notes

- Christina's themes

- culture and arts

- Events

- Fuk 2022

- Fuk 2023

- Fukushima 2017

- Fukushima 2018

- fukushima 2019

- Fukushima 2020

- Fukushima 2021

- general

- global warming

- Humour (God we need it)

- Nuclear

- RARE EARTHS

- Reference

- resources – print

- Resources -audiovicual

- Weekly Newsletter

- World

- World Nuclear

- YouTube

-

RSS

Entries RSS

Comments RSS