Nuclear fusion – expensive, far away in time, and not clean, not safe

Nuclear fusion ‘holy grail’ is not the answer to our energy prayers, Dr Mark Diesendorf questions the claim that nuclear fusion is safe and clean, while Dr Chris Cragg suspects true fusion power is a long way off. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2022/dec/19/nuclear-fusion-holy-grail-is-not-the-answer-to-our-energy-prayers

You [The Guardian] report on the alleged “breakthrough” on nuclear fusion, in which US researchers claim that break-even has been achieved (Breakthrough in nuclear fusion could mean ‘near-limitless energy’, 12 December). To go from break-even, where energy output is greater than total energy input, to a commercial nuclear fusion reactor could take at least 25 years. By then, the whole world could be powered by safe and clean renewable energy, primarily solar and wind.

The claim by the researchers that nuclear fusion is safe and clean is incorrect. Laser fusion, particularly as a component of a fission-fusion hybrid reactor, can produce neutrons that can be used to produce the nuclear explosives plutonium-239, uranium-235 and uranium-233. It could also produce tritium, a form of heavy hydrogen, which is used to boost the explosive power of a fission explosion, making fission bombs smaller and hence more suitable for use in missile warheads. This information is available in open research literature.

The US National Ignition Facility, which did the research, is part of the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, which has a history of involvement with nuclear weaponry. – Dr Mark Diesendorf

University of New South Wales

As someone who once wrote a critical report for the European parliament on fusion power back in the late 1980s, I hate to rain on Arthur Turrell’s splendid parade (The carbon-free energy of the future: this fusion breakthrough changes everything, 13 December).

It is indeed good news that the US National Ignition Facility has got a “net energy gain” of 1.1 MJ from an inertial confinement fusion device using lasers. In this regard, what is really valuable is that the community can now concentrate on this type of reactor, rather than other designs like the tokamak.

However, I am prepared to bet that a true fusion power station is unlikely to be running before my grandchildren turn 70. After all, it has taken 60-odd years and huge amounts of money to get this far.

Dr Chris Cragg

London

Arthur Turrell writes that achieving “net energy gain” has a psychological effect akin to a trumpet to the ear. Well, it might do to him but not to me. Yes, it’s a fantastic achievement for those scientists and engineers who have worked to achieve this proof on concept; well done them. But it will make not one jot of a positive difference to the challenges my children and grandchildren will face as a result of the climate crisis.

We only have years to achieve the changes that are necessary to avoid social catastrophe due to what’s happening to the biosphere, and that’s assuming it’s not already too late. Even the optimists understand that it will be decades before fusion power can contribute to the grid, regardless of this achievement.

Meanwhile the headlines that followed this result, Turrell’s psychological trumpet, simply serve to reassure and detract from the urgency of what needs to be done now.

Dick Willis

Bristol

It is great news that scientists have succeeded in getting more energy out of fusion than they put in. It brings to mind a quote from a past director of the Central Electricity Generating Board: “One day you may get more energy out of nuclear fusion than you put in, but you will never get more money out than you put in.”

Martin O’Donovan

Ashtead, Surrey

Propaganda drive: Nuclear Power 2.0 Eyes Opportunity, Steep Climb in Coal Country

Daniel Moore, Bloomberg Law, 19 Dec 22

The nuclear power industry sees its future in coal country……….

But realizing that vision—now backed by the Biden administration and Congress, with billions earmarked for the plan in last year’s historic infrastructure law—depends on winning over some of the most nuclear-skeptical places in the country. So the Energy Department is on an education mission to gain local support across rural America for what it believes can be a nuclear revival.

“We really, over time, have underestimated the role that social science, political science, sociology, psychology, human geography can all play in our decision-making,” explains Kathryn Huff, the department’s 36-year-old assistant secretary of nuclear energy.

……….. About 80% of nearly 400 operating or shuttered coal power plant sites across the country could be converted to nuclear power plant sites, the Energy Department estimated in September.

………… But in West Virginia, which has no operating nukes, only 38% of residents support building new reactors, according to a public opinion project by the University of Oklahoma and University of Michigan. The state has the second-smallest portion of people who say they see a benefit from nuclear, according to the project, which was funded by the Energy Department and pulled data from 2006 to 2020.

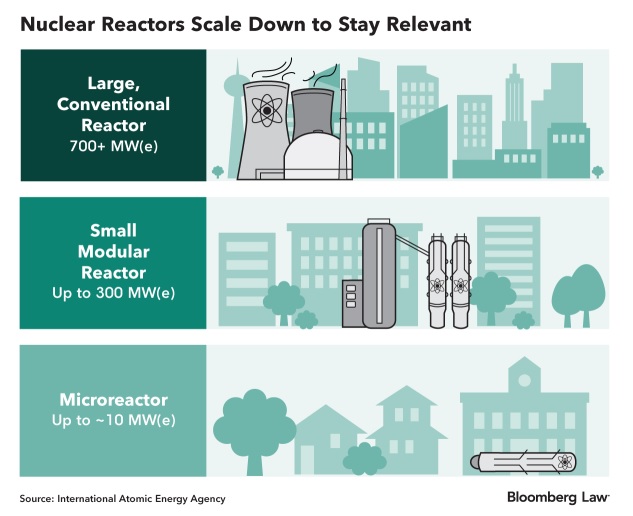

……….. SMRs are key to changing that mindset, with the selling point that they’re not your parent’s nuclear reactors……………………..

A trio of academic studies with 30 researchers will guide the department’s nuclear energy office on community outreach at a DOE-funded test reactor near a shuttered coal plant in Wyoming; a new siting process for temporary nuclear waste storage facilities; and advanced nuclear possibilities in the Arctic, where past nuclear tests have generated deep distrust among indigenous groups.

A trio of academic studies with 30 researchers will guide the department’s nuclear energy office on community outreach at a DOE-funded test reactor near a shuttered coal plant in Wyoming; a new siting process for temporary nuclear waste storage facilities; and advanced nuclear possibilities in the Arctic, where past nuclear tests have generated deep distrust among indigenous groups.

………………… spent nuclear fuel requires on-site storage in bulky steel casks, while a permanent home requires geologic assessments spanning millions of years. And when aging plants do close—as 13 plants have in the last decade—cleanup crews must carefully dismantle the components.

………… The nuclear waste problem is a “gaping hole in the ship of the US nuclear industry,” said Edward McGinnis, who spent almost 30 years at the Energy Department

……. Without a permanent home for waste, “then it’s very difficult to say we should have another generation of nuclear power because we don’t know how to solve the problem of waste from the first generation,” said Tom Isaacs, a nuclear waste expert….

Clean Energy Goal

Lyman from the Union of Concerned Scientists said the number of new local jobs that would come from SMRs are overstated, in part because the largely premanufactured reactors are much smaller and come with lower costs than existing reactors. But he said the unproven plants would still bring potential environmental hazards.

………..Finding markets is crucial for advanced reactors, which hope to roll out by the end of the decade. The department plans to plow as much as $3.2 billion into demonstrating reactors by TerraPower in Wyoming and X-energy in Washington state.

………………………………………….. Environmental groups are sharply split on the issue, said Gary Zuckett, who lobbied for the 1996 West Virginia law that banned nuclear construction until a permanent waste storage facility was established. Zuckett, executive director of West Virginia Citizen Action, considers himself somewhere “in the middle,” as he believes safely operating nuclear plants should stay online to maintain zero-emissions power until more solar and wind can be built.

But communities are concerned about plugging reactors into coal sites, he said.

“I personally don’t see nuclear as our savior,” Zuckett said. “We don’t have a safe, permanent repository for all of this high-level nuclear waste that will be deadly for generations, and so should we really be making more of this?”

Federal incentives could be poured into wind and solar, which are ready to deploy now, said Jim Kotcon, an associate professor at West Virginia University and a leader of the state’s Sierra Club chapter.

“We should adopt the fastest, cheapest, safest and cleanest sources first,” Kotcon said. “Nuclear is none of those.”

……………………………………….. To tackle waste siting, Oklahoma and Michigan researchers hope to define a process for winning consent from communities to host a hypothetical temporary waste site. The DOE is offering $16 million for additional consent-based siting efforts and assessing nearly 1,700 pages of comments in response to a request for information.

The amount of waste SMR generate is the subject of debate—a controversial study in May found small reactors could generate more waste than the industry has led people to believe.

………………………………… Energy Department officials express optimism the appeal to community engagement will work………………………..

The department “will have momentum by the time this administration is done,” Huff said. “It doesn’t matter what political winds shift.”

To contact the reporter on this story: Daniel Moore in Washington at dmoore1@bloombergindustry.com

To contact the editor responsible for this story: Gregory Henderson at ghenderson@bloombergindustry.com https://news.bloomberglaw.com/environment-and-energy/nuclear-power-2-0-eyes-opportunity-steep-climb-in-coal-country

Exaggerated fusion breakthrough is for military purposes.

The claims for a breakthrough in fusion power are not only exaggerated but in reality concerned principally with military objectives.

By Ian Fairlie and David Toke, https://100percentrenewableuk.org/exaggerated-fusion-breakthrough-is-for-military-purposes 18 Dec 22

This test, carried out by the National Ignition Facility at US Government’s Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL), was mainly to facilitate the testing of nuclear weapons. This fact was missed in almost all the hyperbole surrounding the test.

The claims for a breakthrough in fusion power are not only exaggerated but in reality concerned principally with military objectives.

This test, carried out by the National Ignition Facility at US Government’s Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL), was mainly to facilitate the testing of nuclear weapons. This fact was missed in almost all the hyperbole surrounding the test.

Although it is correct that nuclear fusion was achieved, albeit for a trillionth of a second, it was not a first. Ignition has been achieved before in other countries including the UK using a different technology (magnetic confinement) for a few seconds. And the claim that more energy was produced than consumed in the process is specious, as the various reports put out by LLNL compared heat output with electricity input which is like comparing apples and oranges. A true comparison would have taken into account the vast amount of energy consumed to produce the electricity to drive the lasers. And the actual amount of excess heat energy produced (about 20 kettles of boiling water) was paltry.

As Tom Hartsfield, who has been following the progress of the tests by the National Ignition Facility (NIF), put it:

‘the input energy to the laser system is somewhere between 384 and 400 MJ. Consuming 400 MJ and producing 3.15 MJ is a net energy loss greater than 99%. For every single unit of fusion energy it produces, NIF burns at minimum 130 units of energy…….In terms of electrical power, 3.15 MJ would not quite power one 40-watt refrigerator light bulb for a day.’

As Amory Lovins has commented, even if fusion power was free, it would still be uncompetitive with other energy sources. That is because there would be very big capital costs involved, including paying for 19th century steam generator technology to use the fusion power to boil water to drive steam powered electricity generators.

In fact the main purpose of the NIF has not been about advancing civil fusion research, but in advancing the US nuclear weapons programme. A paper in the top science journal Nature published in 2021 discussed an earlier breakthrough, but the main breakthrough described was about nuclear weapons:

‘Housed at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California, the US$3.5-billion facility wasn’t designed to serve as a power-plant prototype, however, but rather to probe fusion reactions at the heart of thermonuclear weapons. After the United States banned underground nuclear testing at the end of the cold war in 1992, the energy department proposed the NIF as part of a larger science-based Stockpile Stewardship Program, designed to verify the reliability of the country’s nuclear weapons without detonating any of them……..With this month’s laser-fusion breakthrough, scientists are cautiously optimistic that the NIF might live up to its promise, helping physicists to better understand the initiation of nuclear fusion — and thus the detonation of nuclear weapons. “That’s really the scientific question for us at the moment,” says Mark Herrmann, Livermore’s deputy director for fundamental weapons physics. “Where can we go? How much further can we go?”

Looking on the bright side, could we say this was a technological breakthrough for mankind? Not really. It is better to examine what its real impact will be for our energy futures – and the answer is precious little. This one test cost around $1.5 billion according to the New York Times, and involved 192 of the world’s largest and most expensive lasers. The disparity in scale and the mismatch with what we really need (inexpensive, practical sources of heat and electricity) are massive.

Another useful yardstick would be how much it would contribute to dealing with climate change. Again nothing. Fusion is not mentioned once as a climate mitigation option in the last IPCC report.

Fusion. Really?

BY KARL GROSSMAN, https://www.counterpunch.org/2022/12/16/fusion-really/— 16 Dec 22

There was great hoopla—largely unquestioned by media—with the announcement this week by the U.S. Department of Energy of a “major scientific breakthrough” in the development of fusion energy.

“This is a landmark achievement,” declared Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm. Her department’s press release said the experiment at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California “produced more energy from fusion than the laser energy used to drive it” and will “provide invaluable insights into the prospects of clean fusion energy.”

“Nuclear fusion technology has been around since the creation of the hydrogen bomb,” noted a CBS News article covering the announcement. “Nuclear fusion has been considered the holy grail of energy creation.” And “now fusion’s moment appears to be finally here,” said the CBS piece

But, as Dr. Daniel Jassby, for 25 years principal research physicist at the Princeton Plasma Physics Lab working on fusion energy research and development, concluded in a 2017 article in the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, fusion power “is something to be shunned.”

His article was headed “Fusion reactor: Not what they’re cracked up to be.”

“Fusion reactors have long been touted as the ‘perfect’ energy source,” he wrote. And “humanity is moving much closer” to “achieving that breakthrough moment when the amount of energy coming out of a fusion reactor will sustainably exceed the amount going in, producing net energy.”

“As we move closer to our goal, however,” continued Jassby, “it is time to ask: Is fusion really a ‘perfect’ energy source?” After having worked on nuclear fusion experiments for 25 years at the Princeton Plasma Physics Lab, I began to look at the fusion enterprise more dispassionately in my retirement. I concluded that a fusion reactor would be far from perfect, and in some ways close to the opposite.”

“Unlike what happens” when fusion occurs on the sun, “which uses ordinary hydrogen at enormous density and temperature,” on Earth “fusion reactors that burn neutron-rich isotopes have byproducts that are anything but harmless,” he said.

A key radioactive substance in the fusion process on Earth would be tritium, a radioactive variant of hydrogen.

Thus there would be “four regrettable problems”—“radiation damage to structures; radioactive waste; the need for biological shielding; and the potential for the production of weapons-grade plutonium 239—thus adding to the threat of nuclear weapons proliferation, not lessening it, as fusion proponents would have it,” wrote Jassby.

“In addition, if fusion reactors are indeed feasible…they would share some of the other serious problems that plague fission reactors, including tritium release, daunting coolant demands, and high operating costs. There will also be additional drawbacks that are unique to fusion devices: the use of a fuel (tritium) that is not found in nature and must be replenished by the reactor itself; and unavoidable on-site power drains that drastically reduce the electric power available for sale.”

“The main source of tritium is fission nuclear reactors,” he went on. Tritium is produced as a waste product in conventional nuclear power plants. They are based on the splitting of atoms, fission, while fusion involves fusing of atoms.

“If adopted, deuterium-tritium based fusion would be the only source of electrical power that does not exploit a naturally occurring fuel or convert a natural energy supply such as solar radiation, wind, falling water, or geothermal. Uniquely, the tritium component of fusion fuel must be generated in the fusion reactor itself,” said Jassby.

About nuclear weapons proliferation, “The open or clandestine production of plutonium 239 is possible in a fusion reactor simply by placing natural or depleted uranium oxide at any location where neutrons of any energy are flying about. The ocean of slowing-down neutrons that results from scattering of the streaming fusion neutrons on the reaction vessel permeates every nook and cranny of the reactor interior, including appendages to the reaction vessel.”

As to “additional disadvantages shared with fission reactors,” in a fusion reactor: “Tritium will be dispersed on the surfaces of the reaction vessel, particle injectors, pumping ducts, and other appendages. Corrosion in the heat exchange system, or a breach in the reactor vacuum ducts could result in the release of radioactive tritium into the atmosphere or local water resources. Tritium exchanges with hydrogen to produce tritiated water, which is biologically hazardous.”

“In addition, there are the problems of coolant demands and poor water efficiency,” he went on. “A fusion reactor is a thermal power plant that would place immense demands on water resources for the secondary cooling loop that generates steam, as well as for removing heat from other reactor subsystems such as cryogenic refrigerators and pumps….In fact, a fusion reactor would have the lowest water efficiency of any type of thermal power plant, whether fossil or nuclear. With drought conditions intensifying in sundry regions of the world, many countries could not physically sustain large fusion reactors.”

“And all of the above means that any fusion reactor will face outsized operating costs,” he wrote.

Fusion reactor operation will require personnel whose expertise has previously been required only for work in fission plants—such as security experts for monitoring safeguard issues and specialty workers to dispose of radioactive waste. Additional skilled personnel will be required to operate a fusion reactor’s more complex subsystems including cryogenics, tritium processing, plasma heating equipment, and elaborate diagnostics. Fission reactors in the United States typically require at least 500 permanent employees over four weekly shifts, and fusion reactors will require closer to 1,000. In contrast, only a handful of people are required to operate hydroelectric plants, natural-gas burning plants, wind turbines, solar power plants, and other power sources,” he wrote.

“Multiple recurring expenses include the replacement of radiation-damaged and plasma-eroded components in magnetic confinement fusion, and the fabrication of millions of fuel capsules for each inertial confinement fusion reactor annually. And any type of nuclear plant must allocate funding for end-of-life decommissioning as well as the periodic disposal of radioactive wastes.”

“It is inconceivable that the total operating costs of a fusion reactor would be less than that of a fission reactor, and therefore the capital cost of a viable fusion reactor must be close to zero (or heavily subsidized) in places where the operating costs alone of fission reactors are not competitive with the cost of electricity produced by non-nuclear power, and have resulted in the shutdown of nuclear power plants,” said Jassby.

“To sum up, fusion reactors face some unique problems: a lack of a natural fuel supply (tritium), and large and irreducible electrical energy drains….These impediments—together with the colossal capital outlay and several additional disadvantages shared with fission reactors—will make fusion reactors more demanding to construct and operate, or reach economic practicality, than any other type of electrical energy generator.”

“The harsh realities of fusion belie the claims of its proponents of ‘unlimited, clean, safe and cheap energy.’ Terrestrial fusion energy is not the ideal energy source extolled by its boosters,” declared Jassby.

Earlier this year, raising the issue of a shortage of tritium fuel for fusion reactors, Science, a publication of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, ran an article headed: “OUT OF GAS, A shortage of tritium fuel may leave fusion energy with an empty tank.” This piece, in June, cited the high cost of “rare radioactive isotope tritium…At $30,000 per gram, it’s almost as precious as a diamond, but for fusion researchers the price is worth paying. When tritium is combined at high temperatures with its sibling deuterium, the two gases can burn like the Sun.”

Then there’s regulation of fusion reactors. An article last year in MIT Science Policy Review noted: “Fusion energy has long been touted as an energy source capable of producing large amounts of clean energy…Despite this promise, fusion energy has not come to fruition after six decades of research and development due to continuing scientific and technical challenges. Significant private investment in commercial fusion start-ups signals a renewed interest in the prospects of near-term development of fusion technology. Successfully development of fusion energy, however, will require an appropriate regulatory framework to ensure public safety and economic viability.”

“Risk-informed regulations incorporate risk information from probabilistic safety analyses to ensure that regulation are appropriate for the actual risk of an activity,” said the article. “Despite the benefits of adopting a risk-informed framework for a mature fission industry, use of risk-informed regulations for the licensing of first-generation commercial fusion technology could be detrimental to the goal of economic near-term deployment of fusion. Commercial fusion technology has an insufficient operational and regulatory experience base to support the rapid and effective use of risk-informed regulations.”

Despite the widespread cheerleading by media about last week’s fusion announcement, there were some measured comments in media. Arianna Skibell of Politico wrote a piece headed “Here’s a reality check for nuclear fusion.” She said “there are daunting scientific and engineering hurdles to developing this discovery into machinery that can affordably turn a fusion reaction into electricity for the grid. That puts fusion squarely in the category of ‘maybe one day.’”

“Here are some reasons for tempering expectations that this breakthrough will yield any quick progress in addressing the climate emergency,” said Skibell. “First and foremost, as climate scientists have warned, the world does not have decades to wait until the technology is potentially viable to zero out greenhouse gas emissions.” She quoted University of Pennsylvania climate scientist Michael Mann commenting: “I’d be more excited about an announcement that U.S. is ending fossil fuel subsidies.”

Henry Fountain in his New York Times online column “Climate Forward,” wrote how “the world needs to sharply cut [carbon] emissions soon…So even if fusion power plants become a reality, it likely would not happen in time to help stave off the near-term worsening effects of climate change. It’s far better, many climate scientists and policymakers say, to focus on currently available renewable energy technologies like solar and wind power to help reach these emissions targets.”

“So if fusion isn’t a quick climate fix, could it be a more long-term solution to the world’s energy needs?” he went on. “Perhaps, but cost may be an issue. The National Ignition Facility at Livermore, where the experiment was conducted, was built for $3.5 billion.”

The Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory has a long history with fusion. It is where, under nuclear physicist Edward Teller, who became its director, the hydrogen bomb was developed. Indeed, he has long been described as “the father of the hydrogen bomb.” The hydrogen bomb utilizes fusion while the atomic bomb, which Teller earlier worked on at Los Alamos National Laboratory, utilizes fission. The development of atomic bombs at Los Alamos led to a nuclear offshoot: nuclear power plants utilizing fission.

Karl Grossman, professor of journalism at State University of New York/College at Old Westbury, and is the author of the book, The Wrong Stuff: The Space’s Program’s Nuclear Threat to Our Planet, and the Beyond Nuclear handbook, The U.S. Space Force and the dangers of nuclear power and nuclear war in space. Grossman is an associate of the media watch group Fairness and Accuracy in Reporting (FAIR). He is a contributor to Hopeless: Barack Obama and the Politics of Illusion.

Bill Gates-backed nuclear demonstration project in Wyoming delayed because Russia was the only fuel source

Catherine Clifford, 16 Dec 22

- Bill Gates nuclear innovation company TerraPower says the operation of its demonstration advanced power reactor will be pushed back at least two years because the only source of fuel for the reactor was Russia.

- The advanced reactor design uses high-assay low-enriched uranium, or HALEU, and was slated to be done in 2028.

- Stakeholders are now calling on the U.S. to secure other sources, or produce it domestically.

……………………………………………. Terrapower’s advanced nuclear plant design, known as Natrium, will be smaller than conventional nuclear reactors, and is slated to cost $4 billion, with half of that money coming from the U.S. Department of Energy. It will offer baseload power of 345 megawatts, with the potential to expand its capacity to 500 megawatts

………………. TerraPower has raised over $830 million in private funding in 2022 and the Congress has appropriated $1.6 billion for the construction of the plant, said Chris Levesque, the CEO of TerraPower. https://www.cnbc.com/2022/12/16/bill-gates-backed-nuclear-demonstration-delayed-by-at-least-2-years.html

Fusion “breakthrough” is largely irrelevant to the climate crisis

Gordon Edwards 15 Dec 22

Just a short commentary on the “fusion breakthrough” this week.

The experiment took place at the Lawrence Radiation Lab, a pre-eminent weapons Laboratory in California once directed by Edward Teller.

Jubilation is felt because, for the first time in over 60 years of effort costing many billions of dollars, a greater amount of energy came out of an extremely short-lived fusion reaction than the amount of energy needed to trigger it in the first place. The net energy gain was about 50 percent.

It all happened very quickly. “The energy production took less time than it takes light to travel one inch,” said Dr Marvin Adams, at the NNSA. (NNSA = National Nuclear Security Administration)

Here are a few details –

1) In an earlier email (www.ccnr.org/fission_fusion_and_efficiency_2022.pdf )I described the “magnetic confinement” concept, whereby an electromagnetic force field holds a very hot plasma of hydrogen gases inside a doughnut-shaped torus (typical of the Tokamak and its close relatives). In this case, “very hot”. Means about 150 million degrees C.

But the breakthrough that is being bally-hooed now, since Tuesday December 13, is a different kind of process altogether, using a concept called “inertial confinement”.

The experiment involved a small pellet about the size of a peppercorn. This pellet contained, in its interior, a mixture of deuterium and tritium gases, two rare hydrogen isotopes. In the experiment, the pellet’s exterior was blasted by x-rays triggered by a battery of 192 very powerful lasers, all targeted on the inner walls of a cylinder made of gold. The lasers generated x-rays on contact with the goldatoms, and those x-rays were focussed by the curving cylinder walls on the little peppercorn-sized pellet in the middle of the gold cylinder.

The x-rays heated the outer shell of the pellet to more than three million degrees, making the exterior of the pellet explode outwards, and (by Newtons “action-reaction” principle) causing the inner gases to be compressed to a very high density at an extremely high temperature, presumably to over 100 million degrees. It is a high-energy kind of implosion, causing fusion to occur in the very centre. The peppercorn “pops”.

2) The experimenters input 2.05 megajoules of energy to the target, and the result was 3.15 megajoules of fusion energy output – that is over 50% more energy than was put in (for a net gain of 1.1 megajoules). This suggests that the fusion reaction inside the pellet may have triggered other fusion reactions.

How much energy is that? Well, a typical household uses about 100,000 megajoules of energy per year, or an average of 273 megajoules per day. So 1.1 megajoules is not much. But it is greater than the input energy.

The Tokamak project now under construction in France for the ITER project, using magnetic confinement, is hoping to have a net energy gain factorof 10 or more (i.e. 10 times as much energy output as energy input).

Earlier this year, in February 2022, the UK JET laboratory announced thatthey had managed to have a fusion reaction last for five seconds. Thereaction produced 59 megajoules of energy, but without a net gain in energy.

3) Most of the news stories about this event state, erroneously, that fusionreactors will not produce any radioactive wastes. This is untrue.

It is true that fusion reactors will not produce high-level; nuclear waste(irradated nuclear fuel), but It is expected that fusion reactors will release an enormous amount of tritium (radioactive hydrogen) to the environment— far more than is currently released by CANDU reactors, which in turn release 30 to 100 times more tritium than light water fission reactors.

Moreover, because of neutron irradiation, the structural materials in a fusion reactor will beome very radioactive. The decommissioning wastes will remain dangerously radioactive for hundreds of thousands of years.

4) Many experts believe it will take at least 20-30 years to have a prototype fusion reactor in operation, even if things go quite well, and more decades will be required to scale it up to a commercial level. Thus fusion energy will be largely irrelevant to the climate emergency we are now facing as all of the critical decision points will have passed before fusion is available.

And, of course, there are no guarantees even then. As one commentator sardonically remarked, fusion energy is 20 years away,it always has been, and perhaps it always will be.

Dismantling Sellafield: the epic task of shutting down a nuclear site

Nothing is produced at Sellafield anymore. But making safe what is left behind is an almost unimaginably expensive and complex task that requires us to think not on a human timescale, but a planetary one

Guardian, by Samanth Subramanian 15 Dec 22,

“……………………………………………………………………….. Laid out over six square kilometres, Sellafield is like a small town, with nearly a thousand buildings, its own roads and even a rail siding – all owned by the government, and requiring security clearance to visit………. having driven through a high-security gate, you’re surrounded by towering chimneys, pipework, chugging cooling plants, everything dressed in steampunk. The sun bounces off metal everywhere. In some spots, the air shakes with the noise of machinery. It feels like the most manmade place in the world.

Since it began operating in 1950, Sellafield has had different duties. First it manufactured plutonium for nuclear weapons. Then it generated electricity for the National Grid, until 2003. It also carried out years of fuel reprocessing: extracting uranium and plutonium from nuclear fuel rods after they’d ended their life cycles. The very day before I visited Sellafield, in mid-July, the reprocessing came to an end as well. It was a historic occasion. From an operational nuclear facility, Sellafield turned into a full-time storage depot – but an uncanny, precarious one, filled with toxic nuclear waste that has to be kept contained at any cost.

Nothing is produced at Sellafield any more. Which was just as well, because I’d gone to Sellafield not to observe how it lived but to understand how it is preparing for its end. Sellafield’s waste – spent fuel rods, scraps of metal, radioactive liquids, a miscellany of other debris – is parked in concrete silos, artificial ponds and sealed buildings. Some of these structures are growing, in the industry’s parlance, “intolerable”, atrophied by the sea air, radiation and time itself. If they degrade too much, waste will seep out of them, poisoning the Cumbrian soil and water.

To prevent that disaster, the waste must be hauled out, the silos destroyed and the ponds filled in with soil and paved over. The salvaged waste will then be transferred to more secure buildings that will be erected on site. But even that will be only a provisional arrangement, lasting a few decades. Nuclear waste has no respect for human timespans. The best way to neutralise its threat is to move it into a subterranean vault, of the kind the UK plans to build later this century.

Once interred, the waste will be left alone for tens of thousands of years, while its radioactivity cools. Dealing with all the radioactive waste left on site is a slow-motion race against time, which will last so long that even the grandchildren of those working on site will not see its end. The process will cost at least £121bn.

Compared to the longevity of nuclear waste, Sellafield has only been around for roughly the span of a single lunch break within a human life. Still, it has lasted almost the entirety of the atomic age, witnessing both its earliest follies and its continuing confusions. In 1954, Lewis Strauss, the chair of the US Atomic Energy Commission, predicted that nuclear energy would make electricity “too cheap to meter”. That forecast has aged poorly. The main reason power companies and governments aren’t keener on nuclear power is not that activists are holding them back or that uranium is difficult to find, but that producing it safely is just proving too expensive.

… The short-termism of policymaking neglected any plans that had to be made for the abominably lengthy, costly life of radioactive waste. I kept being told, at Sellafield, that science is still trying to rectify the decisions made in undue haste three-quarters of a century ago. Many of the earliest structures here, said Dan Bowman, the head of operations at one of Sellafield’s two waste storage ponds, “weren’t even built with decommissioning in mind”.

As a result, Bowman admitted, Sellafield’s scientists are having to invent, mid-marathon, the process of winding the site down – and they’re finding that they still don’t know enough about it. They don’t know exactly what they’ll find in the silos and ponds. They don’t know how much time they’ll need to mop up all the waste, or how long they’ll have to store it, or what Sellafield will look like afterwards. The decommissioning programme is laden “with assumptions and best guesses”, Bowman told me. It will be finished a century or so from now. Until then, Bowman and others will bend their ingenuity to a seemingly self-contradictory exercise: dismantling Sellafield while keeping it from falling apart along the way.

To take apart an ageing nuclear facility, you have to put a lot of other things together first. New technologies, for instance, and new buildings to replace the intolerable ones, and new reserves of money. (That £121bn price tag may swell further.) All of Sellafield is in a holding pattern, trying to keep waste safe until it can be consigned to the ultimate strongroom: the geological disposal facility (GDF), bored hundreds of metres into the Earth’s rock, a project that could cost another £53bn. Even if a GDF receives its first deposit in the 2040s, the waste has to be delivered and put away with such exacting caution that it can be filled and closed only by the middle of the 22nd century.

Anywhere else, this state of temporariness might induce a mood of lax detachment, like a transit lounge to a frequent flyer. But at Sellafield, with all its caches of radioactivity, the thought of catastrophe is so ever-present that you feel your surroundings with a heightened keenness. At one point, when we were walking through the site, a member of the Sellafield team pointed out three different waste storage facilities within a 500-metre radius. The spot where we stood on the road, he said, “is probably the most hazardous place in Europe”.

Sellafield’s waste comes in different forms and potencies. Spent fuel rods and radioactive pieces of metal rest in skips, which in turn are submerged in open, rectangular ponds, where water cools them and absorbs their radiation. The skips have held radioactive material for so long that they themselves count as waste. The pond beds are layered with nuclear sludge: degraded metal wisps, radioactive dust and debris. Discarded cladding, peeled off fuel rods like banana-skins, fills a cluster of 16-metre-deep concrete silos partially sunk into the earth.

More dangerous still are the 20 tonnes of melted fuel inside a reactor that caught fire in 1957 and has been sealed off and left alone ever since. Somewhere on the premises, Sellafield has also stored the 140 tonnes of plutonium it has purified over the decades. It’s the largest such hoard of plutonium in the world, but it, too, is a kind of waste, simply because nobody wants it for weapons any more, or knows what else to do with it.

…………………………………

………………………………… I only ever saw a dummy of a spent fuel rod; the real thing would have been a metre long, weighed 10-12kg, and, when it emerged from a reactor, run to temperatures of 2,800C, half as hot as the surface of the sun. In a reactor, hundreds of rods of fresh uranium fuel slide into a pile of graphite blocks. Then a stream of neutrons, usually emitted by an even more radioactive metal such as californium, is directed into the pile. Those neutrons generate more neutrons out of uranium atoms, which generate still more neutrons out of other uranium atoms, and so on, the whole process begetting vast quantities of heat that can turn water into steam and drive turbines.

During this process, some of the uranium atoms, randomly but very usefully, absorb darting neutrons, yielding heavier atoms of plutonium: the stuff of nuclear weapons. The UK’s earliest reactors – a type called Magnox – were set up to harvest plutonium for bombs; the electricity was a happy byproduct. The government built 26 such reactors across the country. They’re all being decommissioned now, or awaiting demolition. It turned out that if you weren’t looking to make plutonium nukes to blow up cities, Magnox was a pretty inefficient way to light up homes and power factories.

For most of the latter half of the 20th century, one of Sellafield’s chief tasks was reprocessing. Once uranium and plutonium were extracted from used fuel rods, it was thought, they could be stored safely – and perhaps eventually resold, to make money on the side. Beginning in 1956, spent rods came to Cumbria from plants across the UK, but also by sea from customers in Italy and Japan. Sellafield has taken in nearly 60,000 tonnes of spent fuel, more than half of all such fuel reprocessed anywhere in the world. The rods arrived at Sellafield by train, stored in cuboid “flasks” with corrugated sides, each weighing about 50 tonnes and standing 1.5 metres tall.

………….. at last, the reprocessing plant will be placed on “fire watch”, visited periodically to ensure nothing in the building is going up in flames, but otherwise left alone for decades for its radioactivity to dwindle, particle by particle.

ike malign glitter, radioactivity gets everywhere, turning much of what it touches into nuclear waste. The humblest items – a paper towel or a shoe cover used for just a second in a nuclear environment – can absorb radioactivity, but this stuff is graded as low-level waste; it can be encased in a block of cement and left outdoors. (Cement is an excellent shield against radiation. A popular phrase in the nuclear waste industry goes: “When in doubt, grout.”) Even the paper towel needs a couple of hundred years to shed its radioactivity and become safe, though. A moment of use, centuries of quarantine: radiation tends to twist time all out of proportion.

On the other hand, high-level waste – the byproduct of reprocessing – is so radioactive that its containers will give off heat for thousands of years. …………………………….

Waste can travel incognito, to fatal effect: radioactive atoms carried by the wind or water, entering living bodies, riddling them with cancer, ruining them inside out. During the 1957 reactor fire at Sellafield, a radioactive plume of particles poured from the top of a 400-foot chimney. A few days later, some of these particles were detected as far away as Germany and Norway. Near Sellafield, radioactive iodine found its way into the grass of the meadows where dairy cows grazed, so that samples of milk taken in the weeks after the fire showed 10 times the permissible level. The government had to buy up milk from farmers living in 500 sq km around Sellafield and dump it in the Irish Sea.

From the outset, authorities hedged and fibbed. For three days, no one living in the area was told about the gravity of the accident, or even advised to stay indoors and shut their windows. Workers at Sellafield, reporting their alarming radiation exposure to their managers, were persuaded that they’d “walk [it] off on the way home”, the Daily Mirror reported at the time. A government inquiry was then held, but its report was not released in full until 1988. For nearly 30 years, few people knew that the fire dispersed not just radioactive iodine but also polonium, far more deadly. The estimated toll of cancer deaths has been revised upwards continuously, from 33 to 200 to 240. Sellafield took its present name only in 1981, in part to erase the old name, Windscale, and the associated memories of the fire.

The invisibility of radiation and the opacity of governments make for a bad combination. Sellafield hasn’t suffered an accident of equivalent scale since the 1957 fire, but the niggling fear that some radioactivity is leaking out of the facility in some fashion has never entirely vanished. In 1983, a Sellafield pipeline discharged half a tonne of radioactive solvent into the sea. British Nuclear Fuels Limited, the government firm then running Sellafield, was fined £10,000. Around the same time, a documentary crew found higher incidences than expected of leukaemia among children in some surrounding areas. A government study concluded that radiation from Sellafield wasn’t to blame. Perhaps, the study suggested, the leukaemia had an undetected, infectious cause.

It was no secret that Sellafield kept on site huge stashes of spent fuel rods, waiting to be reprocessed. This was lucrative work. An older reprocessing plant on site earned £9bn over its lifetime, half of it from customers overseas. But the pursuit of commercial reprocessing turned Sellafield and a similar French site into “de facto waste dumps”, the journalist Stephanie Cooke found in her book In Mortal Hands. Sellafield now requires £2bn a year to maintain. What looked like a smart line of business back in the 1950s has now turned out to be anything but. With every passing year, maintaining the world’s costliest rubbish dump becomes more and more commercially calamitous.

The expenditure rises because structures age, growing more rickety, more prone to mishap. In 2005, in an older reprocessing plant at Sellafield, 83,000 litres of radioactive acid – enough to fill a few hundred bathtubs – dripped out of a ruptured pipe. The plant had to be shut down for two years; the cleanup cost at least £300m. …………………………………………………………………………….

Waste disposal is a completely solved problem,” Edward Teller, the father of the hydrogen bomb, declared in 1979. He was right, but only in theory. The nuclear industry certainly knew about the utility of water, steel and concrete as shields against radioactivity, and by the 1970s, the US government had begun considering burying reactor waste in a GDF. But Teller was glossing over the details, namely: the expense of keeping waste safe, the duration over which it has to be maintained, the accidents that could befall it, the fallout of those accidents. Four decades on, not a single GDF has begun to operate anywhere in the world. Teller’s complete solution is still a hypothesis.

Instead, there have been only interim solutions, although to a layperson, even these seem to have been conceived in some scientist’s intricate delirium. High-level waste, like the syrupy liquor formed during reprocessing, has to be cooled first, in giant tanks. Then it is vitrified: mixed with three parts glass beads and a little sugar, until it turns into a hot block of dirty-brown glass. (The sugar reduces the waste’s volatility. “We like to get ours from Tate & Lyle,” Eva Watson-Graham, a Sellafield information officer, said.) Since 1991, stainless steel containers full of vitrified waste, each as tall as a human, have been stacked 10-high in a warehouse. If you stand on the floor above them, Watson-Graham said, you can still sense a murmuring warmth on the soles of your shoes.

Even this elaborate vitrification is insufficient in the long, long, long run. Fire or flood could destroy Sellafield’s infrastructure. Terrorists could try to get at the nuclear material. Governments change, companies fold, money runs out. Nations dissolve. Glass degrades. The ground sinks and rises, so that land becomes sea and sea becomes land. The contingency planning that scientists do today – the kind that wasn’t done when the industry was in its infancy – contends with yawning stretches of time. Hence the GDF: a terrestrial cavity to hold waste until its dangers have dried up and it becomes as benign as the surrounding rock.

A glimpse of such an endeavour is available already, beneath Finland. From Helsinki, if you drive 250km west, then head another half-km down, you will come to a warren of tunnels called Onkalo…………. If Onkalo begins operating on schedule, in 2025, it will be the world’s first GDF for spent fuel and high-level reactor waste – 6,500 tonnes of the stuff, all from Finnish nuclear stations. It will cost €5.5bn and is designed to be safe for a million years. The species that is building it, Homo sapiens, has only been around for a third of that time.

………. In the 2120s, once it has been filled, Onkalo will be sealed and turned over to the state. Other countries also plan to banish their nuclear waste into GDFs…. more https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2022/dec/15/dismantling-sellafield-epic-task-shutting-down-decomissioned-nuclear-site

For Heaven’s Sake – Examining the UK’s Militarisation of Space

December 13, 2022, By Dr. David Webb of the Global Network Against Weapons and Nuclear Power in Space

I have been working on behalf of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) with Peter Burt from Dronewars UK on a new joint publication called “For Heaven’s Sake: Examining the UK’s Militarisation of Space”. It was launched in June and looks at the UK’s emerging military space programme and considers the governance, environmental, and ethical issues involved.

The UK’s space programme began in 1952 and the first UK satellite, Ariel 1, was launched in 1962. Black Arrow, a British rocket for launching satellites, was developed during the 1960s and was used for four launches from the Woomera Range Complexin Australia between 1969 and 1971. The final launch was to launch Prospero, the only British satellite to be placed in orbit using a UK rocket in 1971, although the government had by then cancelled the UK space programme. Blue Streak, the UK ballistic missile programme, had been cancelled in 1960andspace projects were considered too expensive to continue. 50 years on and things have changed.

Space is now big business – the commercial space sector has expanded and the cost of launches has decreased. The UK is now treating space as an area of serious interest. The government has also recognised that space is now crucial for military operations. So, the Ministry of Defence (MoD) now has a Space Directorate, which works closely with the UK Space Agency and is responsible for the military space policy and international coordination. UK Space Command, established in April 2021 ,is in charge of the military space programme and is closely linked with US Space Command and US Space Force. While the UK typically frames military developments as being for defensive purposes, they are also capable of offensive use………………………………………………………..

Although many of these launches may be for commercial companies, space use has evolved into a fuzzy military/commercial collaboration and Alexandra Stickings, a space policy and security analyst at the Royal United Services Institute in London, believes that the Shetland and Sutherland spaceports will need military contracts to be viable. She said “I am of the opinion that the proposed spaceports would need the MoD as a customer to survive as well as securing contracts with companies such as Lockheed” and the military will want to diversify their launch capabilities“so the Scottish locations could provide an option for certain future missions.” She also warned that: “There is also a possibility that if these sites become a reality, there will be pressure on the MoD to support them even if the cost is more than other providers.”………………………………..

Although many of these launches may be for commercial companies, space use has evolved into a fuzzy military/commercial collaboration and Alexandra Stickings, a space policy and security analyst at the Royal United Services Institute in London, believes that the Shetland and Sutherland spaceports will need military contracts to be viable. She said

“I am of the opinion that the proposed spaceports would need the MoD as a customer to survive as well as securing contracts with companies such as Lockheed” and the military will want to diversify their launch capabilities“so the Scottish locations could provide an option for certain future missions.” She also warned that: “There is also a possibility that if these sites become a reality, there will be pressure on the MoD to support them even if the cost is more than other providers.”…………………….

…………………… https://safetechinternational.org/for-heavens-sake-examining-the-uks-militarisation-of-space/

Fusion breakthrough thrills physicists, but won’t power your home soon.

A nuclear fusion milestone (with frickin’ laser beams!) is a big deal.

Alas, it could be decades before fusion might actually help clean up our

energy system. A reported breakthrough in fusion energy is generating

enormous excitement amongst scientists and the general public alike — but

you might not want to bet on fusion providing usable energy during your

lifetime.

Experimental results set to be announced by the U.S. Department

of Energy on Tuesday are being hyped as potentially heralding a new era of

zero-carbon energy from the power of a controlled fusion reaction, the same

reaction that powers our sun. Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory has

evidence of a net energy gain in a fusion reaction for the first time,

according to people with knowledge of preliminary results from a recent

experiment, as first reported by the Financial Times. The lab confirmed to

the paper that a successful experiment had recently been conducted at its

National Ignition Facility but said analysis of the results was ongoing.

Canary Media 13th Dec 2022

Very significant barriers to further progress on nuclear fusion

There are two approaches to nuclear fusion: call them doughnuts v lasers.

Magnetic confinement is the more common and longstanding method: picture,

if you can, a doughnut-shaped machine, with nuclear fuel inside it kept

afloat by magnetic fields and heated to incredible temperatures while the

reaction takes place.

The NIF is one of a smaller number of facilities

trying something different: inertial confinement. In the pithy summary of

White House science chief, Arati Prabhakar, yesterday:

“They shot a bunch of lasers at a pellet of fuel [hydrogen plasma] and more energy was

released from that fusion ignition than the energy of the lasers.” The

pellet, encased in diamond, sits in a tiny gold cylinder. By hitting it

with 192 giant lasers for less than 100 trillionths of a second at more

than 3 million celsius, scientists at NIF succeeded in producing 3

megajoules of energy from the 2.05 megajoules it took to make the reaction

happen.

But as good as that sounds, there are very significant barriers to

further progress. “It’s important to say that this is not trying to be

a fusion reactor, it’s simply trying to make fusion happen,” said

Bluck.

“But it lacks almost everything that you need to make a viable

reactor. “So, OK, the energy put in has resulted in a larger amount of

energy coming out – but the big caveat is that it depends where you draw

your perimeter: powering the lasers themselves required way more energy.

You have to draw a slightly artificial dotted line around the vessel to say

there’s been a gain.” The lasers may emit 2.05 megajoules, but they

took about 500 megajoules of energy to power, though defenders of the

experiment say that they are not optimally efficient and can be

significantly improved.

Guardian 14th Dec 2022

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/dec/14/first-edition-nuclear-fusion

Researchers claim a breakthrough in nuclear fusion, but that does not mean fusion as an energy force any time soon.

Researchers have reportedly made a breakthrough in the quest to unlock a

“near-limitless, safe, clean” source of energy: they have got more

energy out of a nuclear fusion reaction than they put in. Nuclear fusion

involves smashing together light elements such as hydrogen to form heavier

elements, releasing a huge burst of energy in the process. The approach,

which gives rise to the heat and light of the sun and other stars, has been

hailed as having huge potential as a sustainable, low-carbon energy source.

However, since nuclear fusion research began in the 1950s, researchers have

been unable to a demonstrate a positive energy gain, a condition known as

ignition. Now, it seems, the Rubicon has been crossed.

But experts have

stressed that while the results would be an important proof of principle,

the technology is a long way from being a mainstay of the energy landscape.

To start with, 0.4MJ is about 0.1kWh – about enough energy to boil a

kettle. “To turn fusion into a power source we’ll need to boost the

energy gain still further,” said Chittenden. “We’ll also need to find

a way to reproduce the same effect much more frequently and much more

cheaply before we can realistically turn this into a power plant.” And

there is another point: the positive energy gain reported ignores the 500MJ

of energy that was put into the lasers themselves.

Guardian 12th Dec 2022

Mini nuclear reactor firms battle it out in UK for approval and government support

Rolls-Royce rivals gear up for mini-nuke race as power system creaks.

Nuclear power is seen as essential to protect Britain from future energy

shocks. Rolls Royce has long been at the vanguard of Britain’s nuclear

industry, with more than half of the UK’s £385m fund to support advanced

projects in the field allocated to Rolls’s mini-nukes programme.

But the

company’s dominance is now being challenged by a new breed of scrappy

start-ups who believe their technology could make Britain a world leader in

nuclear power. “You should have another viable alternative that you’re

supporting,” says Rick Springman, an executive at US mini-nuke company

Holtec. “When you invest in stocks, do you put all your money in one

company?”

Nuclear power is seen as central to the UK’s goal of meeting

its Net Zero targets, improving energy security and reducing its reliance

on Russian oil. Last month, Rolls said its small modular reactors (SMRs),

or so-called mini-nukes, could supply a fifth of the UK’s total

electricity capacity to homes across England and Wales by the end of the

decade. The reactors use existing nuclear technology on a smaller scale

than traditional power plants. Each can generate about 470MW of power and

last at least 60 years. The Government has picked eight sites for new

nuclear projects including Sellafield in Cumbria and Bradwell, Essex, to

place new projects. Other sites such as Trawsfynydd in the Snowdonia

national park are also being considered. Rolls-Royce has chosen four it

would like to build on, earmarked for their existing infrastructure and

connections to the grid.

Rivals want access to these initial sites to prove

their power stations work. Proof that they can power the grid in the UK

could open up opportunities to launch projects abroad. They believe their

technology offers advantages.

London-based Newcleo, for instance, wants to

use some of the UK’s plutonium stockpile for fuel and Last Energy’s

design aims to use more off-the-shelf components, offering a speedier

build. Meanwhile, Holtec is developing a reactor which can be cooled in an

emergency without external power. While Rolls is planning 470MW reactors,

equivalent to more than 150 onshore wind turbines, Holtec plans 160MW

units. Holtec’s reactor could share a site with Rolls-Royce or another

contender.

The forthcoming Hinkley Point C, with power of 3.2GW, is on a

160 hectare site. By comparison, a single Holtec reactor will occupy six

hectares, or about 10 football pitches. The push for approvals comes as

deals elsewhere are signed elsewhere. GE Hitachi Nuclear Energy signed a

deal last year with Canada’s Ontario Power Generation to deliver one of

its BWRX-300 units which could be online as early as 2028. Deals for GE to

build 10 more in Poland followed weeks later. In February, French President

Emmanuel Macron agreed €1bn of funding for EDF’s Nuward SMR which could

be generating electricity by 2030.

Last Energy wrote to the Parliamentary

committee to say that “excessive Government funding for early stage

development activities” can crowd out “entrants and innovation,” and

that having a preferred supplier – a status Rolls-Royce enjoys in the UK –

may limit the field.

Telegraph 12th Dec 2022

European Commission supports French government in funding for small nuclear reactors

On 7 December 2022, the European Commission announced that it has decided,

under the state aid rules, to approve the grant by France of aid to EDF to

support a research and development project for small nuclear reactors.

Practical Law 7th Dec 2022

THE ROBOTS OF FUKUSHIMA: GOING WHERE NO HUMAN HAS GONE BEFORE (AND LIVED)

https://hackaday.com/2022/12/08/the-robots-of-fukushima-going-where-no-human-has-gone-before-and-lived/ by Ryan Flowers, 9 Dec 22

The idea of sending robots into conditions that humans would not survive is a very old concept. Robots don’t heed oxygen, food, or any other myriad of human requirements. They can also be treated as disposable, and they can also be radiation hardened, and they can physically fit into small spaces. And if you just happen to be the owner of a nuclear power plant that’s had multiple meltdowns, you need robots. A lot of them. And [Asianometry] has provided an excellent synopsis of the Robots of Fukushima in the video below the break.

Starting with robots developed for the Three Mile Island incident and then Chernobyl, [Asianometry] goes into the technology and even the politics behind getting robots on the scene, and the crossover between robots destined for space and war, and those destined for cleaning up after a meltdown.

The video goes further into the challenges of putting a robot into a high radiation environment. Also interesting is the state of readiness, or rather the lack thereof, that prompted further domestic innovation.

Obviously, cleaning up a melted down reactor requires highly specialized robots. What’s more, robots that worked on one reactor didn’t work on others, creating the need for yet more custom built machines. The video discusses each, and even touches on future robots that will be needed to fully decommission the Fukushima facility.

For another look at some of the early robots put to work, check out the post “The Fukushima Robot Diaries” which we published over a decade ago.

Ineos Grangemouth refinery: Anti-nuclear campaigners will put up a huge fight against any attempt to build small nuclear reactors – Dr Richard Dixon

The talks between Ineos and Rolls Royce about siting a nuclear reactor at the Grangemouth refinery are a huge gift to campaigners opposed to a new generation of nuclear.

https://www.scotsman.com/news/opinion/columnists/ineos-grangemouth-refinery-anti-nuclear-campaigners-will-put-up-a-huge-fight-against-any-attempt-to-build-reactor-dr-richard-dixon-3944799 By Richard Dixon, 8 Dec 22,

The idea contains the perfect combination of elements needed to ensure its own defeat. This is a plan to build an untested type of nuclear reactor on a site with significant explosion risks all around, in the middle of the most densely populated part of Scotland, with a government that is opposed to nuclear, and, best of all, for a man trade unionists and the public love to hate.

Up to now, nuclear reactors have been placed in out-of-the way places in case the worst happens – from leaks and explosions to terrorist attacks. Or even direct military attacks as in Ukraine. This reactor would be in the middle of the Central Belt, with maximum consequences guaranteed if something goes wrong.

The nuclear industry’s latest wheeze is the small modular reactor (SMR). They make it in a factory, bring it in on trucks and bolt it together on site. There are a number of problems. Firstly they aren’t small, needing an area the size of two football pitches and with the latest proposal having a capacity half as big as the full-scale reactors used by the French nuclear fleet.

They will cost an eye-watering sum: the current estimate is £2 billion but the one certainty about the nuclear industry is that the final cost is always several times what they originally told you. And they would produce proportionally more radioactive waste than the bigger versions. And, of course, there is still no permanent solution for nuclear waste, 70 years on from the start of the civil nuclear programme. Oh yes, and it will be well into the 2030s before an SMR could be built.

The UK Government is keen on the idea, having allocated more than £200 million to their development. But the Scottish Government has been implacably opposed to new nuclear, concentrating instead on energy efficiency and renewable energy. Renewable energy is much cheaper, much faster to install and much, much safer. The scenarios drawn up ahead of the imminent Energy Strategy did not contain any new nuclear power, small, large or otherwise, and the Scottish Government has already been quoted in the press as saying it would block any attempt to build a reactor at Grangemouth.

The Grangemouth site is home to a range of hazardous industries, so much so that Falkirk’s football stadium only has stands on three sides because the fourth would have been inside the Grangemouth ‘blast zone’. Aside from an active war zone, there can’t be a more dangerous place to put a pile of super-hot radioactive material.

Then there is Sir Jim Ratcliffe, twice thwarted in his ambition to become the UK’s Fracker in Chief and a hate figure among the unions for the way he treated workers at Grangemouth. The ideal site-based environmental campaign would be based on this being a dangerous proposal in the wrong place, with hostile politics and a really clear bad guy. This proposal has it all and, if it starts to become real, you can expect an almighty fight.

-

Archives

- January 2026 (259)

- December 2025 (358)

- November 2025 (359)

- October 2025 (376)

- September 2025 (258)

- August 2025 (319)

- July 2025 (230)

- June 2025 (348)

- May 2025 (261)

- April 2025 (305)

- March 2025 (319)

- February 2025 (234)

-

Categories

- 1

- 1 NUCLEAR ISSUES

- business and costs

- climate change

- culture and arts

- ENERGY

- environment

- health

- history

- indigenous issues

- Legal

- marketing of nuclear

- media

- opposition to nuclear

- PERSONAL STORIES

- politics

- politics international

- Religion and ethics

- safety

- secrets,lies and civil liberties

- spinbuster

- technology

- Uranium

- wastes

- weapons and war

- Women

- 2 WORLD

- ACTION

- AFRICA

- Atrocities

- AUSTRALIA

- Christina's notes

- Christina's themes

- culture and arts

- Events

- Fuk 2022

- Fuk 2023

- Fukushima 2017

- Fukushima 2018

- fukushima 2019

- Fukushima 2020

- Fukushima 2021

- general

- global warming

- Humour (God we need it)

- Nuclear

- RARE EARTHS

- Reference

- resources – print

- Resources -audiovicual

- Weekly Newsletter

- World

- World Nuclear

- YouTube

-

RSS

Entries RSS

Comments RSS