A history of nuclear weapons accidents

In early 2009, two nuclear submarines, the French Le Triomphant and British Vanguard, both carrying nuclear weapons, crashed into each other deep in the Atlantic. Fortunately, they were not going fast enough to cause much damage.

Two years earlier, the American Air Force lost six nuclear armed cruise missiles for 36 hours when, unknown to anyone, they were fitted to a B-52 bomber and flown completely unauthorised to a base in Louisiana, left unguarded on the runway until anyone worked out what had happened.

In 2000, the Danish newspaper Jyllands-Posten reported that classified documents obtained by a group of former workers at the Thule airbase suggest that one of four hydrogen bombs on a B-52 bomber that crashed there in 1968 was never found.

There are many instances of false alarms and nuclear bombs nearly being launched. One of the most dangerous of these was stopped by little-known hero Lieutenant Colonel Petrov who, in 1983, probably really did save the world. When he was alerted by an early warning system that five nuclear missiles by America were coming towards the Soviet Union, instead of immediately raising the alarm to his superiors who would have ordered retaliation, he instinctively decided that, if there was an attack, more than five missiles would have been launched and rightly decided that the system was faulty.

These incidents seem to have done nothing to dent the UK and America’s insistence that nuclear weapons safeguard and guarantee peace. The old Cold War politics of nuclear deterrents can seemingly do nothing to deter democratic interference on social media or the global impact of COVID-19. Like scary but lumbering dinosaurs, our trident submarines roam the ocean’s depths with enormous fire power – just one missile can kill more than 10 million people – while Russian President Vladimir Putin interferes with democratic elections in the West for less than the price of a non-nuclear fighter jet.https://bylinetimes.com/2020/10/21/the-nuclear-treaty-dividing-the-world/

60 years since nuclear war very nearly happened

Nearly 60 years ago this week, we were one argument away from nuclear war, Lessons from the Cuban Missile Crisis remain important, yet Americans largely ignore foreign policy. Deseret News, By Arthur Cyr, Columnist Oct 20, 2020 The Cuban Missile Crisis occurred more than a half century ago, but the lessons remain important. Nuclear arms control talks between Moscow and Washington have derailed, and UN arms embargo of Iran has ended.

Current dangers of fatal military miscalculation may equal the height of the Cold War. In the United States, our military presence in the Mideast fuels fitful debate but not sustained discussion of serious strategic risks involved.

During Oct. 22-28, 1962, the Cuba crisis dominated world attention, as Washington and Moscow sparred on the edge of thermonuclear war. Lessons include difficulty of securing accurate intelligence and the unpredictability of events.

On Oct. 14, 1962, U.S. reconnaissance photos revealed the Soviet Union was placing offensive nuclear missiles in Cuba, despite contrary assurances. On Oct. 16, after thorough review and analysis, National Security Adviser McGeorge Bundy informed President John F. Kennedy……….

The initial pressure for military attack dissipated. Kennedy deftly delayed intense pressures for war, while avoiding angry confrontation.

Lessons of the crisis include the importance of disciplined objective intelligence analysis, and communicating with opponents. Then and now, U.S. presidential leadership is essential.

Today, U.S. troops are in the Mideast close to forces from Russia, Iran, Israel, Syria, Turkey and various armed insurgent groups. Yet Americans remain preoccupied with domestic concerns and largely ignore foreign policy.

Cuban Missile Crisis lessons remain important, ignored at great peril.

Arthur I. Cyr is Clausen Distinguished Professor at Carthage College and author of “After the Cold War.” Contact acyr@carthage.edu https://www.deseret.com/opinion/2020/10/20/21525956/cold-war-cuban-missile-crisis-jfk-nuclear-weapons

Ionising radiation – the tragedy of the ”radium girls”.

They weren’t just making paints, they were doing the painting, too. According to NPR, US Radium hired scores of girls and young women — as young as just 11-years-old — to paint watch dials with the glow-in-the-dark, radium-based paint. As if just working with the paint wasn’t bad enough, they were also encouraged to put the brush between their lips and twirl it into a point. It was the best way to get truly precise numbers and brush strokes, but with each lick of the brush, they were swallowing radium.

the human body isn’t great at telling the difference between radium and calcium. Radium gets absorbed into the bones just like calcium does, and when that happens, the rot starts.

Writer and historian Kate Moore documented the cases of the Radium Girls (via The Spectator) and found that there were a whole host of symptoms. Some started suffering from chronic exhaustion. For many, it started with their teeth — one by one, those teeth would start to decay and rot. When they were removed, their gums wouldn’t heal. In some cases, the jaw would just simply disintegrate at the dentist’s touch. Bad breath was common. Skin became so delicate that the slightest touch would tear open wounds. Ulcers formed for some, and those that were pregnant bore stillborn babies.

THE RADIUM GIRLS HAD TO BE BURIED IN LEAD-LINED COFFINS

The Radium Girls weren’t just sick, they were very literally radioactive. Mollie Maggia was exhumed in 1927, in the hopes that her bones would give still-living Radium Girls the evidence they needed to win in court. According to Popular Science, her coffin was lifted out of the ground, and her body? It glowed. That wasn’t entirely surprising, considering her bones were found to be highly radioactive — and considering radium’s half-life is 1,600 years, they’re not going to stop glowing any time soon.

Eventually, 16 separate sites around Ottawa would be classified as Superfund sites.

NPR Illinois says that many have been cleaned up, but as of 2018, there was at least one site — a 17-acre plot of land on the Fox River — that still remained a highly radioactive and terrifying legacy of the Radium Girls.

THE MESSED UP TRUTH ABOUT THE RADIUM GIRLS https://www.grunge.com/181092/the-messed-up-truth-about-the-radium-girls/ BY DEBRA KELLY/DEC. JULY 14, 2020

History is filled with episodes that prove mankind is just sort of making everything up as it goes. There’s no shortage of things that can kill us or do horrible, terrible things to our soft and squishy bodies, and every time we think we know about them all, it turns out there’s something else lurking around the corner.

And sometimes, it’s disguised as something awesome. Need proof? Look no further than the Radium Girls.

Yes, that radium. Today, the Royal Society of Chemistry says there’s really only one use for radium — targeted cancer treatments, because it’s so good at killing cells. It was first discovered in 1898 by Marie and Pierre Curie, after they extracted a single milligram from ten tons of a uranium ore called pitchblende. And it was pretty darn cool. It glowed, and seriously, how exciting is that? Unfortunately, it was also deadly — as the so-called Radium Girls would find out.

In 1951, Winston Churchill suggested dropping nuclear bombs on Russia

BOMBS AWAY Winston Churchill suggested dropping nuclear bombs on Russia in 1951.The Sun, Abe Hawken

BOMBS AWAY Winston Churchill suggested dropping nuclear bombs on Russia in 1951.The Sun, Abe HawkenThe then leader of the opposition is said to have wanted his war strategy to involve using nuclear strikes to bomb Russia and China into submission.

He thought the best way to end the conflict was to give Russia an “ultimatum” and if they refused, he would threaten 20 to 30 cities with atom bombs.

Churchill then wanted to warn Russia it was “imperative” the civilian population of each named city was “immediately evacuated”.

He was convinced Russia would refuse their terms so he discussed plans to bomb “one of the targets, and if necessary, additional ones”.

Churchill hoped that by the third attack the Kremlin would eventually meet their terms.

The bombshell plans have come to light in a memorandum written by the New York Times general manager Julius Ochs Adler, according to The Times.

In it, he describes a conversation the pair had during lunch at Churchill’s home in Kent on Sunday, April 29, 1951……….

Richard Toye, head of history of the University of Exeter, found the note in papers belonging to the New York Times Company.

He said Churchill recommended a threat like this in 1949 when the Soviet Union did not have nuclear weapons.

However, he added that it was a revelation he was still contemplating a similar threat two years later.

He told The Times: “One can question his judgment at this point.”…………https://www.thesun.co.uk/news/uknews/12621015/winston-churchill-nuclear-bombs-russia/

Central Asia’s toxic nuclear legacy

According to Kyrgyz official data, the gamma radiation on tailings pit surfaces are within 17-60 mR/hr; however, in the damaged areas, radiation levels reach 400-500 mR/hr. An exposure to 100 mSv a year (a millisievert, mSv, is equal to 100 milliroentgens, mR) or 10,000 mR is the point where an increase in cancer is clearly evident. At 400-500 mR/hr this would be achieved in 20-25 hours, or just one day. Radionuclides and heavy metals from these tailing pits and dumps are seeping into the surface and groundwater, polluting water and farmland and increasing the risk of cancer for local people.

According to Kyrgyz official data, the gamma radiation on tailings pit surfaces are within 17-60 mR/hr; however, in the damaged areas, radiation levels reach 400-500 mR/hr. An exposure to 100 mSv a year (a millisievert, mSv, is equal to 100 milliroentgens, mR) or 10,000 mR is the point where an increase in cancer is clearly evident. At 400-500 mR/hr this would be achieved in 20-25 hours, or just one day. Radionuclides and heavy metals from these tailing pits and dumps are seeping into the surface and groundwater, polluting water and farmland and increasing the risk of cancer for local people.

Birth anomalies are an additional indicator of environmental radioactive contamination. A study by the Institute of Medical Problems showed that the incidence of birth defects in Mailuu-Suu was three times higher than in the country’s second largest city of Osh. Studies have correlated birth defects to the distance of the parents’ residences from radioactive waste sites. Polluted water is the major factor causing the development of congenital malformations, according to research by the Institute of Medical Problems.

Mailuu-Suu: Cleaning up Central Asia’s toxic uranium legacy https://www.thethirdpole.net/2020/09/02/mailuu-suu-cleaning-up-central-asias-toxic-uranium-legacy/

Countries must set aside territorial disputes and work together to clean up radioactive waste seeping into rivers and farmland in the Ferghana Valley – causing an environmental and health catastrophe for people living in the region Janyl Madykova, September 2, 2020 Political tensions between countries in Central Asia have intensified since the collapse of the Soviet Union. Along with border conflicts and water disputes, problems have arisen from residual radioactive waste located in the Kyrgyz town of Mailuu-Suu in the Ferghana Valley, which has caused widespread pollution of river and farmland, and led to major impacts on the health and economy of people in Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan.

Industrial-scale uranium mining began in Mailuu-Suu during the Soviet era in 1946 and lasted until 1968. Uranium ore from Europe and China was also processed in Mailuu-Suu during this time.

As a result, the small town of 24,000 people is now surrounded by about 3 million cubic metres of uranium waste left in 23 tailings pits and 13 dumps. These sites have contaminated the Mailuu-Suu river, a major tributary of the Syr Darya which flows through Kyrgyzstan and into Uzbekistan, carrying radioactive waste into the densely populated Ferghana Valley.

The biggest problem is that earthquakes, landslides and heavy rainfall events have intensified in recent years, destroying uranium tailing storage sites along the river and mountain slopes, contaminating surrounding areas. A number of international organisations have worked to prevent further disasters in Mailuu-Suu. The World Bank has allocated more than USD 11 million to clean up uranium tailings. The European Commission launched an initiative in 2015 to remediate the most dangerous sites in Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan.

However, the pollution remains, and Central Asian countries must cooperate to prevent further environmental disasters in the Ferghana Valley, as well as mitigate economic damage and resolve political issues.

A town built on radioactive waste

According to the state surveys there are 92 radioactive and toxic storage facilities across Kyrgyzstan today. The most dangerous of these are the Mailuu-Suu uranium sites, because of numerous hazards threatening the tailing pits. Were these tailing pits destabilised, they would have potentially catastrophic environmental consequences for Kyrgyzstan and the neighbouring countries of Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan, with the radioactive waste contaminating the river as well as the soil and irrigated farmland surrounding it.

Uranium was first discovered in the region in 1933, and within 20 years 10,000 tonnes of uranium oxide was extracted in Mailuu-Suu. Residual radioactive waste in southern Kyrgyzstan currently poses a major environmental threat to the densely populated parts of the Ferghana Valley, home to about 14 million people.

Landslides are the major risk. There are more than 200 landslide-prone locations around Mailuu-Suu. There was little such threat in the 1940s, but landslide activity has intensified since 1954 due to increased rainfall. Landslides in Mailuu-Suu occurred several times in 1988, 1992 and 2002, damaging infrastructure and altering water flow. The most dangerous landslide is Koi-Tash, which happened in 2017 and could block the riverbed and spread radioactive contamination down the river.

The 1950s saw one of the most salient examples of the danger posed by vulnerable waste dumps. In April 1958, as a result of rainfall and high seismic activity, an alluvial dam collapsed into tailings pit #7 in Mailuu-Suu, pushing more than 400,000 cubic metres of radioactive waste into the Mailuu-Suu river, which then spread 30-40 km downstream in irrigated farmland in Uzbekistan. The effects of this disaster have lasted to this day, with the radioactive contamination of the river and surrounding soil and vegetation causing major health problems and fatalities. Such disasters also heighten tensions between the regional states. Continue reading

Racism in nuclear bomb testing, bombing of Japanese people, and nuclear waste dumping

Langston Hughes voiced the opinion that until racial injustice on home ground in the United States ceases, “it is going to be very hard for some Americans not to think the easiest way to settle the problems of Asia is simply dropping an atom bomb on colored heads there.”[25] While his statement was made in 1953, near the eighth anniversary of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings, it remains equally relevant today, as we approach the 75th anniversary

Memorial Days: the racial underpinnings of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings , Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, Elaine Scarry, Elaine Scarry is the author of Thermonuclear Monarchy: Choosing between Democracy and Doom and The Body in Pain: the Making and Unmaking of the World. She is Cabot Profess… By Elaine Scarry, August 3, 2020

This past Memorial Day, a Minneapolis police officer knelt on the throat of an African-American, George Floyd, for 8 minutes and 46 seconds. Seventy-five years ago, an American pilot dropped an atomic bomb on the civilian population of Hiroshima. Worlds apart in time, space, and scale, the two events share three key features. Each was an act of state violence. Each was an act carried out against a defenseless opponent. Each was an act of naked racism. ……….

Self-defense was not an option for any one of the 300,000 civilian inhabitants of the city of Hiroshima, nor for any one of the 250,000 civilians in Nagasaki three days later. We know from John Hersey’s classic Hiroshima that as day dawned on that August morning, the city was full of courageous undertakings meant to increase the town’s collective capacity for self-defense against conventional warfare, such as the clearing of fire lanes by hundreds of young school girls, many of whom would instantly vanish in the 6,000° C temperature of the initial flash, and others of whom, more distant from the center, would retain their lives but lose their faces.[2] The bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki initiated an era in which—for the first time on Earth and now continuing for seven and a half decades—humankind collectively and summarily lost the right self-defense. No one on Earth—or almost no one on Earth[3]—has the means to outlive a blast that is four times the heat of the sun or withstand the hurricane winds and raging fires that follow………

Centuries of political philosophers have asked, “What kind of political arrangements will create a noble and generous people?” Surely such arrangements cannot be ones where a handful of men control the means for destroying at will everyone on Earth from whom the means of self-defense have been eliminated……..

When Americans first learned that the people of Hiroshima and Nagasaki had been collectively vaporized in less time than it takes for the heart to beat, many cheered. But not all. Black poet Langston Hughes at once recognized the moral depravity of executing 100,000 people and discerned racism as the phenomenon that had licensed the depravity: “How come we did not try them [atomic bombs] on Germany… . They just did not want to use them on white folks.”[4] Although the building of the weapon was completed only after Germany surrendered on May 7, 1945, Japan had been designated the target on September 18, 1944, and training for the mission had already been initiated in that same month.[5] Black journalist George Schuyler wrote: “The atom bomb puts the Anglo-Saxons definitely on top where they will remain for decades”; the country, in its “racial arrogance,” has “achieved the supreme triumph of being able to slaughter whole cities at a time.”[6]

Still within the first year (and still before John Hersey had begun to awaken Americans to the horrible aversiveness of the injuries), novelist and anthropologist Zora Neale Hurston denounced the US president as a “butcher” and scorned the public’s silent compliance, asking, “Is it that we are so devoted to a ‘good Massa’ that we feel we ought not to even protest such crimes?”[7] Silence—whether practiced by whites or people of color—was, she saw, a cowardly act of moral enslavement to a white supremacist. Continue reading

Virtual tours planned at Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum and the Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum

Virtual tours planned at atomic bomb museums, https://www3.nhk.or.jp/nhkworld/en/news/20200721_43/?fbclid=IwAR2KZ-D8gWm-K1Yl8WVBDpUyobELxvI6Hm-DiWxtZYPBmyS8mo9BOneLd2E 21 Jul 20, Two Japanese museums dedicated to documenting the 1945 atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki plan to offer virtual tours online in cooperation with an international NGO devoted to the elimination of nuclear weapons.They are planning the events as the number of international visitors to these museums has dropped sharply due to the coronavirus pandemic.

Kawasaki Akira, a member from the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons, or ICAN, unveiled the plan online on Monday.

The exhibits at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum and the Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Museum will be shown live on Instagram. Volunteers and researchers from universities will explain the displays in English.

The Hiroshima museum will hold the virtual tour on Wednesday for about 30 minutes after closing time, between 6:30 p.m. and 7p.m. Japan time.

The Nagasaki museum will hold it on Friday for about 30 minutes before opening time, between 8:00 a.m. and 8:30 a.m. Japan time.

Kawasaki said his group and the museums want to do everything possible online as various activities have been canceled due to the coronavirus pandemic.

He said he wants to offer young people abroad an opportunity to find out about the damage and aftereffects of the atomic bombings of the two cities.

The Anthropocene, begun in 16th Century colonialism, slavery -? for repair in 21st Century post-Covid-19 recovery

Why the Anthropocene began with European colonisation, mass slavery and the ‘great dying’ of the 16th century, The Conversation, Mark Maslin, Professor of Earth System Science, UCL, Simon Lewis, Professor of Global Change Science at University of Leeds and, UCL June 25, 2020 The toppling of statues at Black Lives Matter protests has powerfully articulated that the roots of modern racism lie in European colonisation and slavery. Racism will be more forcefully opposed once we acknowledge this history and learn from it. Geographers and geologists can help contribute to this new understanding of our past, by defining the new human-dominated period of Earth’s history as beginning with European colonialism.Today our impacts on the environment are immense: humans move more soil, rock and sediment each year than is transported by all other natural processes combined. We may have kicked off the sixth “mass extinction” in Earth’s history, and the global climate is warming so fast we have delayed the next ice age.

We’ve made enough concrete to cover the entire surface of the Earth in a layer two millimetres thick. Enough plastic has been manufactured to clingfilm it as well. We annually produce 4.8 billion tonnes of our top five crops and 4.8 billion livestock animals. There are 1.4 billion motor vehicles, 2 billion personal computers, and more mobile phones than the 7.8 billion people on Earth.

All this suggests humans have become a geological superpower and evidence of our impact will be visible in rocks millions of years from now. This is a new geological epoch that scientists are calling the Anthropocene, combining the words for “human” and “recent-time”. But debate still continues as to when we should define the beginning of this period. When exactly did we leave behind the Holocene – the 10,000 years of stability that allowed farming and complex civilisations to develop – and move into the new epoch?

Five years ago we published evidence that the start of capitalism and European colonisation meet the formal scientific criteria for the start of the Anthropocene.

Our planetary impacts have increased since our earliest ancestors stepped down from the trees, at first by hunting some animal species to extinction. Much later, following the development of farming and agricultural societies, we started to change the climate. Yet Earth only truly became a “human planet” with the emergence of something quite different. This was capitalism, which itself grew out of European expansion in the 15th and 16th century and the era of colonisation and subjugation of indigenous peoples all around the world.

In the Americas, just 100 years after Christopher Columbus first set foot on the Bahamas in 1492, 56 million indigenous Americans were dead, mainly in South and Central America. This was 90% of the population. Most were killed by diseases brought across the Atlantic by Europeans, which had never been seen before in the Americas: measles, smallpox, influenza, the bubonic plague. War, slavery and wave after wave of disease combined to cause this “great dying”, something the world had never seen before, or since.

In North America the population decline was slower but no less dramatic due to slower colonisation by Europeans. US census data suggest the Native American population may have been as low as 250,000 people by 1900 from a pre-Columbus level of 5 million, a 95% decline.

This depopulation left the continents dominated by Europeans, who set up plantations and filled a labour shortage with enslaved workers. In total, more than 12 million people were forced to leave Africa and work for Europeans as slaves. ……….

In addition to the critical task of highlighting and tackling the racism within science, perhaps geologists and geographers can also make a small contribution to the Black Lives Matter movement by unflinchingly compiling the evidence showing that when humans started to exert a huge influence on the Earth’s environment was also the start of the brutal European colonisation of the world.

In her insightful book, A Billion Black Anthropocenes or None, the geography professor Kathryn Yusoff makes it very clear that predominantly white geologists and geographers need to acknowledge that Europeans decimated indigenous and minority populations whenever so-called progress occurred.

Defining the start of the human planet as the period of colonisation, the spread of deadly diseases and transatlantic slavery, means we can face the past and ensure we deal with its toxic legacy. If 1610 marks both a turning point in human relations with the Earth and our treatment of each other, then maybe, just maybe, 2020 could mark the start of a new chapter of equality, environmental justice and stewardship of the only planet in the universe known to harbour any life. It’s a struggle nobody can afford to lose. https://theconversation.com/why-the-anthropocene-began-with-european-colonisation-mass-slavery-and-the-great-dying-of-the-16th-century-140661

USA’s secret plan for “dominance”by exploding a nuclear bomb on the moon

REVEALED: The US wanted to detonate a nuclear bomb on the MOON in 1959 to counter the Soviet lead in the space race and show dominance

- New details of an astonishing scheme, first detailed in 1999, have been revealed

- John Greenewald, Jr writes in Secrets from the Vault about numerous plans

- He says a nuclear bomb on the moon was ‘one of the stupider things’ considered

- The US government also wanted to build a military base on the moon by 1966

By HARRIET ALEXANDER FOR DAILYMAIL.COM

PUBLISHED: 10:28 AEST, 21 June 2020 | UPDATED: 15:01 AEST, 21 June 2020

New details about a U.S. plan to blow up a nuclear bomb on the moon as a Cold War ‘show of dominance’ have been revealed in a recently-published book.

The secret mission, code-named Project A119, was conceived at the dawn of the space race by an Air Force division located at New Mexico‘s Kirtland Air Force Base.

A report authored in June 1959 entitled ‘A Study of Lunar Research Flights’ explained plans to explode the bomb on the moon’s ‘terminator’ – the area between the part of the surface that is illuminated by the sun, and the part that’s dark.

The explosion would have likely been visible with the naked eye from Earth because the military had planned to add sodium to the bomb, which would glow when it exploded

A nuclear bomb on the surface of the moon was definitely one of the stupider things the government could do,’ said John Greenewald, Jr., author of Secrets from the Vault.

The book, published in April, details some of the more surreal suggestions made in history.

Greenewald, 39, has been interested in U.S. government secrets since he was 15 and has filed more than 3,000 Freedom of Information Requests……… https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-8443569/US-wanted-detonate-nuclear-bomb-moon-1959-dominance.html

The Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty- its promise and its failure

Now, nuclear disarmament is at a standstill, existing treaties have either been dismantled or at risk, development in underway of new types of nuclear weapons with new missions and lowered threshold of use, and threats of use of nuclear weapons have been sounded.

Now, nuclear disarmament is at a standstill, existing treaties have either been dismantled or at risk, development in underway of new types of nuclear weapons with new missions and lowered threshold of use, and threats of use of nuclear weapons have been sounded.

|

25 Years After the Indefinite Extension of The Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty: A Field of Broken Promises and Shattered Visions InDepth News, By Tariq Rauf 11 May 20, VIENNA (IDN) – “I long ago took to heart the words of Omar Bradley, spoken virtually a half century ago, when he observed, having seen the aftermath of the bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, thus: ‘We live in an age of nuclear giants and ethical infants. We live in a world that has achieved brilliance without wisdom, power without conscience. We’ve unlocked the mysteries of the atom and forgotten the lessons of the Sermon on the Mount. We know more about war than we know about peace, more about killing than we know about living’.”

These remarks were made by General George Lee Butler, the last Commander of the United States Strategic Air Command (SAC) in a speech in Ottawa, Canada, on 11 March 1999. “Why a country that makes atomic bombs would ban fireworks”, asked a child at the United Nations kindergarten in New York. ………..Decision on the Indefinite Extension of the NPT The momentous decision to extend the NPT indefinitely was taken on Thursday, 11 May 1995, in the 17th plenary meeting of the review and extension conference starting at 12:10 PM New York time. The President of the 1995 NPT Review and Extension Conference (NPTREC), Ambassador Jayantha Dhanapala (Sri Lanka), began the meeting by saying that, “I apologize to all delegations for the delay in convening this meeting, but I assure them that it was for very good reasons. Consultations were taking place amongst delegations to ensure that our work should progress smoothly. We also commence a little after high noon to intensify the drama of the occasion”. Dhanapala informed the delegates that three proposals were on the table regarding options for the extension of the Treaty, these were: (1) a proposal by Mexico, calling for indefinite extension along with a number of procedural elements; (2) a proposal submitted by Canada on behalf of 103 States parties and subsequently sponsored by eight additional States parties, calling for the indefinite extension with no added elements; and (3) a proposal submitted by Indonesia and 10 States parties and subsequently sponsored by three additional States parties; calling for an extension for rolling fixed periods of twenty-five years with a review and extension conference at the end of each fixed period to conduct an effective and comprehensive review of the operation of the Treaty, and for the Treaty to be extended for the next fixed period of twenty-five years unless the majority of the parties to the Treaty decided otherwise at the review and extension conference………. The principles and objectives contained recommendations and actions covering all three pillars of the NPT: (1) nuclear disarmament; (2) nuclear-non-proliferation; and (3) peaceful uses of nuclear technologies. Continue reading |

Looking back to May 1986 – the exodus from Kiev, after the Chernobyl nuclear catastrophe

|

From the Guardian archive Chernobyl nuclear disaster Exodus from Kiev: aftermath of

Chernobyl nuclear accident – archive, 1986 Chernobyl nuclear accident – archive, 1986

5 May 1986: Moscow has seen many Russians arriving by train from Kiev in the disaster area Martin Walker The first real signs of alarm among the Soviet public began to emerge over the weekend as Russians arriving by train from Kiev in the Chernobyl disaster area, began saying frankly that they were worried by radiation. “I am very glad to be able to be in Moscow at this time,” a young father, with two daughters, said on arrival at the Kiev Station in Moscow yesterday. “Of course I am worried about radiation. It is not something any government can control.”

There was no sign of any organised evacuation, and the exodus seems to be spontaneous, provoked by the highly publicised visit to the Chernobyl nuclear disaster area last Friday by the Prime Minister, Mr Nikolai Ryzhkov, and the party ideology chief, Mr Yegor Ligachev, perhaps the two most powerful men in the country after Mr Mikhail Gorbachev. Their visit to the area was clearly intended to continue the official campaign of reassurance and to fend off panic. It seems to be having the opposite effect, however. …… Japanese experts testing Moscow water, milk and foods in their embassy reported yesterday that they had found “low but distinct radiation,” which was the more alarming since winds had not carried the radiation direct to Moscow. The Japanese embassy and Japanese companies are now flying in milk, fruit and vegetables for their personnel. The head of the International Atomic Energy Agency, Dr Hans Blix, is to arrive in Moscow today, and Soviet authorities have promised to give him “full documentation” of the nuclear accident. But it is not clear whether he will be allowed to visit the site, or if he will be restricted to Moscow.

It emerged over the weekend that some rudimentary precautions were being recommended to the Soviet population. Soviet friends report that their children in Moscow schools had been told that some foodstuffs had been accidentally infected with rat poison in the city warehouses, and that all vegetables should be scrubbed and peeled. In Kiev, the Greek and Lebanese students still there have been warned by their Soviet liaison officials not to bathe or shower in the local water, nor to drink tap water, and to stay away from the local lake reservoir known as the Sea of Kiev. Bottled water had disappeared from Moscow shops yesterday…….. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/may/05/exodus-from-kiev-aftermath-of-chernobyl-nuclear-accident-archive-1986

|

|

|

Ordinary people can beat the nuclear establishment: it’s been done before

Housewives and Fishmongers Defeat the U.S. Nuclear Establishment https://allthingsnuclear.org/gkulacki/housewives-and-fishmongers-defeat-the-u-s-nuclear-establishment

It was the height of the McCarthy era. The nuclear arms race was just beginning and opposing it was called un-American. But a crew of Japanese fishermen and a small group of Japanese housewives would change the debate. Their signature campaigns set off a chain reaction of global awareness that eventually led the United States to sign an international agreement banning nuclear weapons tests in the atmosphere, under water, and in outer space.

Castle Bravo

On March 1, 1954 the United States tested a nuclear weapon 1,000 times more powerful than the bomb that destroyed Hiroshima. The blast over the Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands left a crater on the ocean floor 6,500 feet wide and 250 feet deep. Radioactive debris from the blast rained down over a 7,000 square mile area.

This wasn’t the first U.S. nuclear weapon tested in the Marshall Islands—an impoverished nation of scattered coral atolls close to the equator in the central Pacific Ocean—nor would it be the last. Between 1946 and 1958 the United States conducted 67 explosive nuclear weapons tests there.. The United States took control of the islands from Japan during WWII and administered them as part of a Trust Territory of the Pacific under a mandate from the United Nations until 1986.

It’s hard to imagine a more egregious betrayal of that trust. Several hours after the test—code named Castle Bravo—radioactive debris began falling on the unsuspecting inhabitants of the Rongelap atoll 150 km to the east of the crater. Children ran out to play in the snow-like powder that covered the island. Some ate it. The United States waited two days before evacuating the endangered islanders to a safer atoll more than 650km to the southeast.

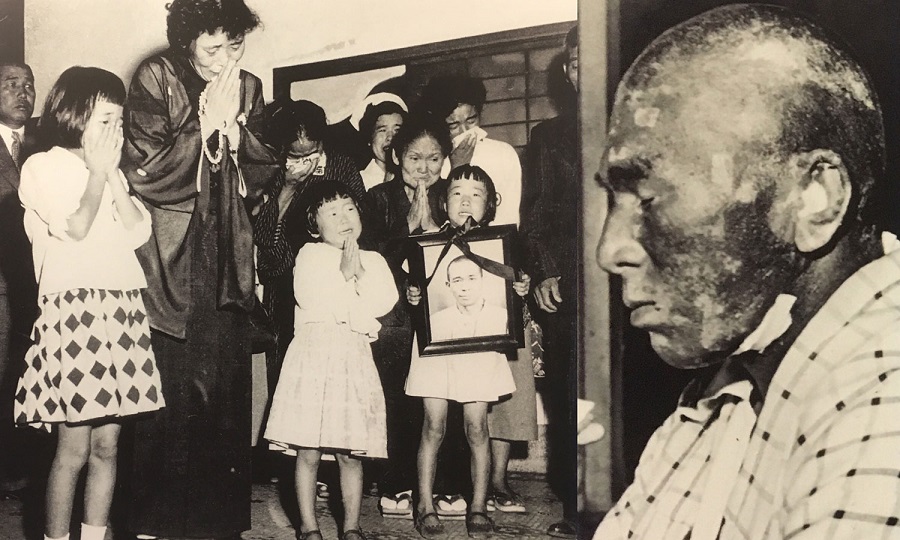

Lucky dragon

A Japanese fishing boat called the Daigo Fukuryū Maru—the Lucky Dragon No. 5—got caught in a dirty rain of radioactive fallout from the Castle Bravo test. It pelted the fisherman for hours, stuck to their exposed skin and got into their eyes, noses and mouths. By the time they returned to Japan two weeks later their skin was burned, their hair was falling out, and their gums were bleeding. Six months after returning home, Aikichi Kuboyama, the ship’s radio operator, died from his exposure.

The Japanese media was fascinated and appalled by their story, which was reported around the world. Memories of the horrors of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were revived and amplified. But this time the Japanese public, and people throughout Asia, began to realize the potential danger was not confined to the site of the explosion. They could all become victims of the atomic bomb. Indonesia’s President Suharto put it this way in his opening address to the first ever international conference of the newly independent nations of Africa and Asia in the city of Bandung in April 1955:

“The food that we eat, the water that we drink, yes, even the very air that we breathe can be contaminated by poisons originating from thousands of miles away. And it could be that, even if we ourselves escaped lightly, the unborn generations of our children would bear on their distorted bodies the marks of our failure to control the forces which have been released on the world.”

The Suganami appeal

Japanese fishmongers saw their businesses crippled by widespread public fear of eating “A-bombed tuna.” Five-hundred of them met in Tokyo’s famous Tsukiji Market and decided to launch a signature campaign against atomic and hydrogen bombs. Their efforts inspired the Suganami City Assembly to pass a supportive resolution.

Six months earlier a group of housewives had begun meeting in the newly opened Suganami Community Center to read books and discuss social issues, including the causes of war, with the center’s part-time director, Kaoru Yasui. After the Castle Bravo test, they joined with neighbors to form the Suganami Council and launched an appeal to the people of Japan, and the world, to ban hydrogen bombs.

The housewives, fishmongers and many other groups who collected signatures were not part of an organized movement. They were ordinary people. Within a month, 250,000 had signed. By the end of 1955 it was 20 million. According to some accounts, nearly a third of the population of Japan eventually signed the appeal.

The notoriety of the Japanese campaign, along with increased scientific investigation of the distribution and consequences of radioactive fallout, created global public health concerns and inspired people to press the nuclear weapons states to stop testing. The U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff and the U.S. nuclear weapons laboratories were strongly opposed to any agreement on testing. But President Eisenhower joined the Soviets in a testing moratorium in 1958 and negotiations on a treaty began in Geneva. This eventually led to the entry into force the Partial Test Ban Treaty in 1963, which banned nuclear testing in the atmosphere as well as underwater and in space.

This year the survivors of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki 75 years ago have launched an appeal to ban nuclear weapons. You can do your part to advance the process of nuclear disarmament by lending your signature to the cause.

The lingering horror of the nuclear bomb tests at Maralinga, South Australia

|

Maralinga is 54 kilometres north-west of Ooldea, in South Australia’s remote Great Victoria Desert. Between 1956 and 1963 the British detonated seven atomic bombs at the site; one was twice the size of the bomb dropped on Hiroshima. There were also the so-called “minor trials” where officials deliberately set fire to or blew up plutonium with TNT — just to see what would happen. One location called “Kuli” is still off-limits today, because it’s been impossible to clean up. I went out to the old bomb sites with a group of Maralinga Tjarutja people, who refer to the land around ground zero as “Mamu Pulka”, Pitjantjatjara for “Big Evil”. “My dad passed away with leukaemia. We don’t know if it was from here, but a lot of the time he worked around here,” says Jeremy Lebois, chairperson of the Maralinga Tjarutja council. Thirty per cent of the British and Australian servicemen exposed to the blasts also died of cancer — though the McClelland royal commission of 1984 was unable to conclude that each case was specifically caused by the tests. It’s not until you stand at ground zero that you fully realise the hideous power of these bombs. Even after more than 60 years, the vegetation is cleared in a perfect circle with a one kilometre radius. “The ground underneath is still sterile, so when the plants get down a certain distance, they die,” explains Robin Matthews, who guided me around the site. The steel and concrete towers used to explode the bombs were instantly vaporised. The red desert sand was melted into green glass that still litters the site. Years ago it would have been dangerous to visit the area, but now the radiation is only three times normal — no more than what you get flying in a plane. The Line of FireAustralia was not the first choice for the British, but they were knocked back by both the US and Canada. Robert Menzies, Australia’s prime minister at the time, said yes to the tests without even taking the decision to cabinet first. David Lowe, chair of contemporary history at Deakin University, thinks Australia was hoping to become a nuclear power itself by sharing British technology, or at least to station British nuclear weapons on Australian soil. “In that period many leaders in the Western world genuinely thought there was a real risk of a third world war, which would be nuclear,” he says. The bombs were tested on the Montebello Islands, at Emu Field and at Maralinga. At Woomera in the South Australian desert, they tested the missiles that could carry them. The Blue Streak rocket was developed and test-fired right across the middle of Australia, from Woomera all the way to the Indian Ocean, just south of Broome. This is known as “The Line of Fire” The Line of Fire from Woomera to Broome is, funnily enough, the same distance from London to Moscow,” Mr Matthews says. Just as the Maralinga Tjarutja people were pushed off their land for the bomb tests, the Yulparitja people were removed from their country in the landing zone south of Broome. Not all the Blue Streak rockets reached the sea. Some crashed into the West Australian desert. The McClelland royal commission showed that the British were cavalier about the weather conditions during the bomb tests and that fallout was carried much further than the 100-mile radius agreed to, reaching Townsville, Brisbane, Sydney and Adelaide. “The cavalier attitude towards Australia’s Indigenous populations was appalling and you’d have to say to some extent that extended towards both British and Australian service people,” Professor Lowe says. There are also questions over whether people at the test sites were deliberately exposed to radiation. “You can’t help but wonder the extent to which there was a deliberate interest in the medical results of radioactive materials entering the body,” Professor Lowe says. “Some of this stuff is still restricted; you can’t get your hands on all materials concerning the testing and it’s quite likely both [British and Australian] governments will try very hard to ensure that never happens.” Project SunshineWe do know that there was a concerted effort to examine the bones of deceased infants to test for levels of Strontium 90 (Sr-90), an isotope that is one of the by-products of nuclear bombs. These tests were part of Project Sunshine, a series of studies initiated in the US in 1953 by the Atomic Energy Commission. They sought to measure how Sr-90 had dispersed around the world by measuring its concentration in the bones of the dead. Young bones were chosen because they were particularly susceptible to accumulating the Sr-90 isotope. Around 1,500 exhumations took place, in both Britain and Australia — often without the knowledge or permission of the parents of the dead. Again, it was hard to prove conclusively that spikes in the levels of Strontium 90 during the test period caused bone cancers around the world. The Maralinga tests occurred during a period that Professor Lowe describes as “atomic utopian thinking”. “Remember at that time Australians were uncovering pretty significant discoveries of uranium and they hoped that this would unleash a vast new capacity for development through the power of the atom,” he says. Some of the schemes were absurdly optimistic. Project Ploughshare grew out of a US program which proposed using atomic explosions for industrial purposes such as canal-building. In 1969 Australia and the US signed a joint feasibility study to create an instant port at Cape Keraudren in the Kimberley using nuclear explosions. The plan was dropped, but it was for economic not environmental or social reasons. The dream (or was it a nightmare?) of sharing nuclear weapons technology with the British was never realised. All Australia got out of the deal was help building the Lucas Heights reactor. The British did two ineffectual clean-ups of Maralinga in the 1960s. The proper clean-up between 1995 and 2000 cost more than $100 million, of which Australia paid $75 million. It has left an artificial mesa in the desert containing 400,000 cubic metres of plutonium contaminated soil. The Maralinga Tjarutja people received only $13 million in compensation for loss of their land, which was finally returned to them in 1984. As we were leaving the radiation zone, the Maralinga Tjarutja people spotted some kangaroos in the distance. Over the years some of the wildlife has started to return. Mr Lebois takes it as a good sign. “Hopefully, hopefully everything will come back,” he says. |

|

Studies on Chernobyl nuclear disaster show that it’s relevant today, and for the future

Each meltdown has impelled design, operational, and regulatory changes, increasing the cost of nuclear power. Today, says the industry, the technology is safer and more vital than ever. No other source of electricity can offer so much baseload power with so few carbon emissions. But who can make money when a single US Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) inspection costs $360,000?

For the current US administration, the remedy for waning profits lies in cutting inspection hours. In a July 2019 proposal, which drew heavily on nuclear industry recommendations, the NRC also suggested crediting utility self-assessments as “inspections” and discontinuing press releases about problems of “low to moderate safety or security significance.” Translation: fewer inspections, less transparency, and weaker environmental and health oversight at the nation’s nuclear power plants.

The cause, costs, and consequences of the 1986 Chernobyl accident loom large in these battles. Was Chernobyl a fluke, the result of faulty technology and a corrupt political system? Or did it signal a fundamentally flawed technological system, one that would never live up to expectations?

Even simple questions are subject to debate. How long did the disaster last? Who were the victims, and how many were there? What did they experience? Which branches of science help us understand the damage? Whom should we trust? Such questions are tackled, with markedly different results, in Serhii Plokhy’s Chernobyl, Adam Higginbotham’s Midnight in Chernobyl, Kate Brown’s Manual for Survival, and HBO’s Chernobyl (created by Craig Mazin).

Serhii Plokhy’s book and Craig Mazin’s miniseries, both entitled Chernobyl, focus primarily on the accident and its immediate aftermath. Both build on the standard plotline embraced by nuclear advocates.

In this narrative, Soviet love of monumental grandeur—or “gigantomania”—led to the selection and construction of Chernobyl’s RBMK1 design: an enormous 1000-megawatt reactor, powered by low-enriched uranium fuel, moderated by graphite, and cooled by water. The utterly unique RBMK had fundamental design flaws, hidden by corrupt state apparatchiks obsessed with secrecy, prestige, and productivism. Operators made inexcusable errors. The accident was inevitable. But the inevitability, Plokhy and Mazin affirm, was purely Soviet.

Plokhy gives more backstory. The enormous scale of Soviet industrialization put huge strains on supply chains, resulting in shoddy construction. Some of the men in charge had no nuclear background. The pressure to meet production quotas—and the dire consequences of failure—led bureaucrats and engineers to cut corners.

For both Plokhy and Mazin, these conditions at Chernobyl came to a head during a long-delayed safety test. When the moment to launch the test finally arrived, shortly before midnight on April 25, 1986, there was confusion about how to proceed. The plant’s deputy chief engineer, Anatolii Diatlov, who did have extensive nuclear experience, believed he knew better than the woefully incomplete manuals. He pushed operators to violate the poorly written test protocol. (Disappointingly, Mazin’s miniseries portrays Diatlov more as a deranged bully than as someone with meaningful operational knowledge.)

The reactor did not cooperate: its power plummeted, then shot back up. Operators tried to reinsert the control rods. The manual didn’t mention that the RBMK could behave counterintuitively: in other reactor models, inserting control rods would slow down the fission reaction, but in the RBMK—especially under that night’s operating conditions—inserting the rods actually increased the reactivity. Steam pressure and temperature skyrocketed. The reactor exploded, shearing off its 2000-ton lid. Uranium, graphite, and a suite of radionuclides flew out of the core and splattered around the site. The remaining graphite in the core caught fire.

At first, plant managers didn’t believe that the core had actually exploded. In the USSR—as elsewhere—the impossibility of a reactor explosion underwrote visions of atomic bounty. Nor did managers believe the initial radiation readings, which exceeded their dosimeters’ detection limits. Their disbelief exacerbated and prolonged the harm, exposing many more people to much more radiation than they might have otherwise received. Firefighters lacked protection against radiation; the evacuation of the neighboring town of Pripyat was dangerously delayed; May Day parades proceeded as planned. Anxious to blame human operators—instead of faulty technology or (Lenin forbid!) a broken political system—the state put the plant’s three top managers on trial, in June 1987, their guilt predetermined.

Mazin’s miniseries follows a few central characters. Most really existed, though the script takes considerable liberties. The actions of the one made-up character, a Belarusian nuclear physicist, completely defy credibility. But hey, it’s TV. Dramatic convention dictates that viewers must care about the characters to care about the story. Familiar Cold War tropes are on full display: defective design, craven bureaucrats, and a corrupt, secrecy-obsessed political system. A few anonymous heroes also appear: firefighters, divers, miners, and others who risked their lives to limit the damage.

Nuclear advocates—many of whom believe that Chernobyl was a fluke, one whose lessons actually improved the industry’s long-term viability—object to the unrealistically gory hospital scenes portraying acute radiation sickness. But these advocates should feel appeased by the closing frames, which ignore the long-term damage caused by the accident.

Instead, the miniseries skates over post-1987 events in a few quick captions. The managers went to prison, a scientist committed suicide, people were evacuated. Yes, controversy persists over the number of casualties (31? That was the official Soviet number. How about 4,000? That’s the number issued by the Chernobyl Forum, an entity that includes representatives from the World Health Organization, the International Atomic Energy Agency, and other international organizations. As for the 41,000 cancers suggested by a study published in the International Journal of Cancer—that number isn’t even mentioned). But all is under control now, thanks to the new confinement structure that will keep the area “safe” for a hundred years. Mazin himself insists that the show isn’t antinuclear.

Instead, the miniseries skates over post-1987 events in a few quick captions. The managers went to prison, a scientist committed suicide, people were evacuated. Yes, controversy persists over the number of casualties (31? That was the official Soviet number. How about 4,000? That’s the number issued by the Chernobyl Forum, an entity that includes representatives from the World Health Organization, the International Atomic Energy Agency, and other international organizations. As for the 41,000 cancers suggested by a study published in the International Journal of Cancer—that number isn’t even mentioned). But all is under control now, thanks to the new confinement structure that will keep the area “safe” for a hundred years. Mazin himself insists that the show isn’t antinuclear.

Plokhy also addresses the accident’s role in the breakup of the USSR. In 2006, Mikhail Gorbachev famously speculated that “the nuclear meltdown at Chernobyl, even more than my launch of perestroika, was perhaps the real cause of the collapse of the Soviet Union.” Plokhy delivers details. Ukrainian dissidents trained their writerly gaze on Chernobyl, vividly describing the damage. Street demonstrations depicted the accident and its coverup as “embodiments of Moscow’s eco-imperialism.” This vision spread and morphed, animating protests in Belarus—also severely contaminated by the accident—and elsewhere. Chernobyl served as Exhibit A for why the republics should shed the Soviet yoke.

If you’re hoping for clear technical explanations, however, you’ll be disappointed. A stunning error mars the first few pages: Plokhy declares that each RBMK produced 1 million megawatts of electricity. This is off by a factor of 1,000. Typo? No, because he doubles down in the next sentence, affirming that the station produced 29 billion megawatts of electricity in 1985. He gets the orders of magnitude right later on, but these early missteps undermine reader confidence. Muddled technical descriptions and uninformative diagrams add to the confusion.

Readers seeking to understand the technology should turn instead to journalist Adam Higginbotham’s Midnight in Chernobyl. He uses global nuclear history to illuminate Soviet efforts to manage the Chernobyl crisis. By comparing the crisis to reactor accidents elsewhere, Higginbotham shows that deep vulnerabilities are widespread. Plokhy’s engineers and managers seem bumbling, verging on incompetent. Higginbotham’s more nuanced portrayal reflects how complex engineering projects of all types necessitate informed improvisation. The three-dimensional world doesn’t faithfully obey manuals. Adjustments are always required.

Readers seeking to understand the technology should turn instead to journalist Adam Higginbotham’s Midnight in Chernobyl. He uses global nuclear history to illuminate Soviet efforts to manage the Chernobyl crisis. By comparing the crisis to reactor accidents elsewhere, Higginbotham shows that deep vulnerabilities are widespread. Plokhy’s engineers and managers seem bumbling, verging on incompetent. Higginbotham’s more nuanced portrayal reflects how complex engineering projects of all types necessitate informed improvisation. The three-dimensional world doesn’t faithfully obey manuals. Adjustments are always required.

Higginbotham and Plokhy differ most starkly in their treatment of Soviet reactor choice. In the1960s, technocrats weighed the RBMK design against the VVER,2 the Soviet version of a pressurized light water reactor similar to those sold by Westinghouse and used in the United States. For Plokhy, it’s simple. The VVER was “safe.” The RBMK was not, but its size and cost appealed to Soviet productivism.

Higginbotham, however, wisely relies on Sonja Schmid’s pathbreaking Producing Power: The Pre-Chernobyl History of the Soviet Nuclear Industry (2015) to show that reactor safety isn’t a yes-no proposition. Plutonium-producing reactors similar to the Soviet RBMK (albeit half its size) existed in North America and Western Europe. Like nine of its French cousins, the RBMK could be refueled while continuing to operate. This presented significant advantages: light water reactors had to shut down for refueling, which entailed several weeks of outage. Even the risks presented by RBMK design vulnerabilities seemed manageable. “Nuclear experts elsewhere considered the RBMK design neither technologically novel nor particularly worrisome,” Schmid writes, noting that “what we consider good and safe always depends on context.” In the Soviet context, “selecting the RBMK made very good sense.”

Neither Schmid nor Higginbotham absolves the Soviet technopolitical system. The specific circumstances that led to Chernobyl’s explosions might not recur. But, as sociologist Charles Perrow has been arguing since his 1983 book Normal Accidents, highly complex technological systems create unpredictable situations, which inevitably lead to system failures. The question is not whether an accident of Chernobyl’s gravity can happen elsewhere, but how to prepare for the consequences when it does.

That’s one of the questions Kate Brown considers in Manual for Survival. Offering a wealth of new information and analysis, Brown speeds past the reactor explosion. Instead, she focuses on dozens of previously untold stories about how people coped with their newly radioactive lives.

That’s one of the questions Kate Brown considers in Manual for Survival. Offering a wealth of new information and analysis, Brown speeds past the reactor explosion. Instead, she focuses on dozens of previously untold stories about how people coped with their newly radioactive lives.

Brown’s protagonists include women who worked at a wool factory fed by contaminated sheep and butchers ordered to grade meat according to radioactivity. Ukraine, we learn, kept serving as the Soviet breadbasket, despite food radiation levels that exceeded norms. The concentrations of radionuclides were biomagnified by receptive organisms and ecologies, such as mushrooms, wild boar, and the Pripyat Marshes. Defying expectations, some foods, over time, have even become more contaminated.

Brown’s descriptions add historical flesh to arguments first developed by Olga Kuchinskaya, in her 2014 book on Belarus’s Chernobyl experience, The Politics of Invisibility: Public Knowledge about Radiation Health Effects after Chernobyl.

Since the first studies of bomb survivors in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, science on the biological effects of radiation exposure has been subject to controversy. Like all scientific work, these early survivor studies had limitations. Exposure estimates were unreliable.

The largest study began data collection five years after the Hiroshima and Nagasaki blasts, so it didn’t include people who died or moved between 1945 and 1950. Another problem lies in the applicability of these studies. Bomb exposures, such as those in Japan, mostly consist of high, external doses from one big blast. Yet postwar exposures have mainly consisted of low doses, delivered steadily over a long period. They often involve internal exposures—such as inhalation of radioactive particles or consumption of irradiated food—which can be deadlier.

Irrespective of their limitations, however, the findings of these survivor studies have served as the basis for establishing regulatory limits for all types of radiation exposures. Critics argue that extrapolating from the Japan data underestimates low-dose effects: If you’ve already decided that the only possible health effects are the ones you’ve already found, surely you’re missing something? Among other limitations, studies of external gamma radiation exposures cannot illuminate the long-term health effects of inhaling radioactive alpha particles.

Brown injects the work of Dr. Angelina Gus’kova into this story. Gus’kova started treating radiation-induced illnesses in the 1950s, while working at the top-secret Mayak plutonium plant (where the radioactive spills from a 1957 accident continue to contaminate people, land, and water). A neurologist, Gus’kova made observations that extended beyond the narrow cancer focus of most Western practitioners who studied the health effects of radiation exposure. Her patients displayed a wide range of symptoms, which Gus’kova and her colleagues dubbed “chronic radiation syndrome.” Not that they neglected cancer: a 40-year study of 1.5 million people who lived near Mayak found significantly higher cancer and death rates than those reported in Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

The Soviet rubric of “chronic radiation syndrome” did not exist in the West. Yet Gus’kova’s findings did align with those of dissident scientists in the US and the UK. Thomas Mancuso, for example, was pushed out of the US Atomic Energy Commission because he refused to give the Hanford plutonium plant a clean bill of health after finding that workers there sustained high rates of cardiovascular disease, immune system damage, and other illnesses.

Alice Stewart, meanwhile, was shunned by the British establishment after her 1956 research showed that x-raying pregnant women increased the risk of cancer and leukemia in their children by 50 percent. Over the years, these and other scientists whose data challenged the findings of American and European nuclear establishments found themselves sidelined and defunded.

In tandem with perestroika, Chernobyl opened communication between Soviet and Western nuclear experts, engendering what Brown calls an “unholy alliance.” In 1990, the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) sent a mission to Belarus and Ukraine to assess radiation damage. Belarusian scientists reported rising rates of many diseases in contaminated areas. Nevertheless, the IAEA team rejected radiation as a possible cause. Such correlations didn’t appear in Western data.

Instead, the IAEA teams used dose estimates provided by distant Moscow colleagues and ignored local Belarusian and Ukrainian descriptions of people’s actual consumption habits, which included significant amounts of contaminated food and milk. The IAEA assessments neglected the internal exposures resulting from this consumption. Yet these assessments now serve as international reference points. “Underestimating Chernobyl damage,” Brown warns, “has left humans unprepared for the next disaster.”

For some, hope springs eternal. In 2017, Chernobyl’s “New Safe Confinement” finally became operational, after two decades of design and construction. This $1.7 billion structure aims to contain the spread of radioactive rubble while workers inside dismantle the reactor and its crumbling sarcophagus. Ownership was transferred from the builders of the structure to the Ukrainian government in July 2019.

At the transfer ceremony, newly elected Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky announced a tourism development plan for the radioactive exclusion zone, including a “green corridor” through which tourists could travel to gawk at the remains of Soviet hubris. “Until now, Chernobyl was a negative part of Ukraine’s brand,” declared Zelensky, who was nine years old when the reactor exploded. “It’s time to change.” (Zelensky further demonstrated his dedication to “branding” two weeks after this ceremony, when he emphasized his recent stay in a Trump hotel during his now-infamous phone conversation with the US president.)

Change also seems possible to Plokhy, who optimistically predicts that new reactor designs will be “cheaper, safer, and ecologically cleaner.” But Allison Macfarlane, who chaired the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission under Obama, recently noted that these “new” options are actually “repackaged designs from 70 years ago.” They still produce significant quantities of highly radioactive, long-lived waste.

Meanwhile, regulators in France—the world’s most nuclear nation—are taking the opposite approach from the United States’ NRC. Rather than rolling back oversight, France is intensifying inspections of their aging reactor fleet. After four decades of operation, many French reactors have begun to leak and crack. Keeping them operational will cost at least $61 billion. Despite the phenomenal cost, there are many who believe such an investment in the nuclear future is worthwhile.

Brown is far less sanguine about our nuclear future. Predictably, she has been denounced for believing marginal scientists and relying too heavily on anecdotal evidence. She does occasionally go overboard in suggesting conspiracy. Cover-ups clearly occurred on many occasions, but sometimes people were just sticking to their beliefs, trapped by their institutional and disciplinary lenses. Brown’s absence of nuance on this point matters, because the banality of ignorance—its complicity in all forms of knowledge production—can be more dangerous than deliberate lies: more systemic, harder to detect and combat.

Overall, though, Brown is on the right track. Many modes of scientific inquiry aren’t equipped to address our most urgent questions. Clear causal chains are a laboratory ideal. The real world brims with confounding variables. Some scientists studying Chernobyl’s “exclusion zone”—the region officially declared uninhabitable due to contamination—are trying new techniques to grapple with this reality. Tim Mousseau and Anders Møller, for example, collect data on the zone in its ecological entirety, rather than focusing on single organisms. Their findings belie romantic tales of wildlife resurgence (such as the one offered up by a 2011 PBS special on the radioactive wolves of Chernobyl). They too have met resistance.

How, then, can we harness the immense power of scientific analysis while also acknowledging its limitations? The nuclear establishment is quick to lump its opponents together with climate change deniers and anti-vaxxers. Some may deserve that. But much dissident science is well executed. So how do we, the lay public, tell the difference? How can dissent and uncertainty serve, not as a block to action, but as a call?

One way: we can refuse to see Chernobyl and its kin as discrete events of limited duration. Brown, for example, treats Chernobyl as an acceleration of planetary-scale contamination that began with the atomic arms race.

Let’s be clear: the contamination continues. After the triple meltdown at Fukushima, scientists found highly radioactive, cesium-rich microparticles in Tokyo, 150 miles south of the accident site. When inhaled, such particles remain in human lungs, where their decay continues to release radioactivity for decades. Contaminants from future accidents will, in turn, accrete on the radioactive residues of their predecessors.

And, we might add, on the ocean floor. The Russian state-run firm Rosatom recently announced the inauguration of its first floating reactor, towed across the melting Arctic to serve a community in Siberia: yet another manifestation of how climate change favors nuclear development. Rosatom is currently negotiating contracts for reactors (floating and otherwise) in some 30 countries, from Belarus to Bangladesh, Egypt to South Africa.

Threatened, the US nuclear industry sees Russian expansion as “another reason that the United States should maintain global leadership in nuclear technology exports.” And so we hurtle forward: rolling back oversight, acceleration unchecked.

This article was commissioned by Caitlin Zaloom.

-

Archives

- December 2025 (358)

- November 2025 (359)

- October 2025 (377)

- September 2025 (258)

- August 2025 (319)

- July 2025 (230)

- June 2025 (348)

- May 2025 (261)

- April 2025 (305)

- March 2025 (319)

- February 2025 (234)

- January 2025 (250)

-

Categories

- 1

- 1 NUCLEAR ISSUES

- business and costs

- climate change

- culture and arts

- ENERGY

- environment

- health

- history

- indigenous issues

- Legal

- marketing of nuclear

- media

- opposition to nuclear

- PERSONAL STORIES

- politics

- politics international

- Religion and ethics

- safety

- secrets,lies and civil liberties

- spinbuster

- technology

- Uranium

- wastes

- weapons and war

- Women

- 2 WORLD

- ACTION

- AFRICA

- Atrocities

- AUSTRALIA

- Christina's notes

- Christina's themes

- culture and arts

- Events

- Fuk 2022

- Fuk 2023

- Fukushima 2017

- Fukushima 2018

- fukushima 2019

- Fukushima 2020

- Fukushima 2021

- general

- global warming

- Humour (God we need it)

- Nuclear

- RARE EARTHS

- Reference

- resources – print

- Resources -audiovicual

- Weekly Newsletter

- World

- World Nuclear

- YouTube

-

RSS

Entries RSS

Comments RSS