What Is Radiation Poisoning?

What Is Radiation Poisoning? Here’s What to Know About the Disease Seen on HBO’s ‘Chernobyl’

What Is Radiation Poisoning? Here’s What to Know About the Disease Seen on HBO’s ‘Chernobyl’

And what’s the deal with those iodine pills?, Health, By Christina Oehler June 03, 2019 “…….

Chernobyl miniseries could not be made in the real Chernobyl wasteland – radiation would have damaged the film kit

Not at the real Chernobyl wasteland that still stands today in what is now Ukraine, but rather in Lithuania, mainly at Chernobyl’s sister power plant, Ignalina, with other portions filmed in suitably… (subscribers only) https://www.telegraph.co.uk/travel/destinations/europe/lithuania/articles/chernobyl-tv-show-real-filming-locations/

New Hampshire citizens’ group to monitor radiation emanating from the Seabrook Power plant.

Group looks to monitor Seabrook power plant radiation, Seacoastonline.com By

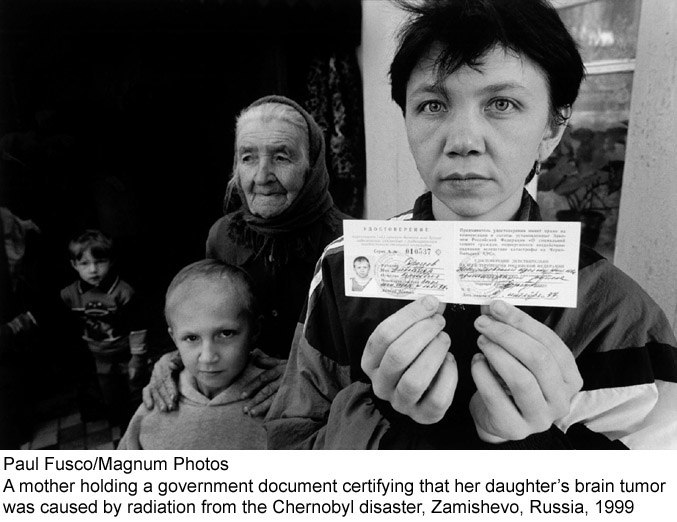

Misleading and dangerous – the downplaying of Chernobyl’s radiation risks

Downplaying the danger of Chernobyl https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/may/26/downplaying-the-danger-of-chernobyl Downplaying the danger of Chernobyl https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2019/may/26/downplaying-the-danger-of-chernobyl

A travel article on a wildlife trip to the Chernobyl disaster zone failed to highlight the continuing radiation threat to people, animals and plants, write David Lowry and Ian Fairlie

Tom Allan’s report of his holiday inside the Chernobyl exclusion zone (Nuclear reaction, Travel, 25 May) was both misleading and dangerous in its assertions. He gives the impression that the radiation dangers are minimal: “less radiation risk than on a single transatlantic flight”, according to his ornithologist Belarusian guide, Valery Yurko. The problem around Chernobyl is not average radiation exposure but the millions of highly radioactive hotspots of radioactive particles spewed from inside the destroyed Chernobyl reactor core. The entire exclusion zone area has suffered from serious forest fires in the 33 years since the catastrophe, re-suspending these hot particles into the atmosphere and spreading them around.

Mr Allan also inaccurately asserts “so far, the effect of radiation on the animal populations has not been visible”. I suggest he consult the extensive academic research of Professor Tim Mousseau of the department of biological sciences at the University of South Carolina, and his international colleagues, where he will find extensively set out the crippling effect of the radioactive contamination on both flora and fauna. • Tom Allan is poorly informed about the risks of radiation. The external radiation he received may be low, but what about the radioactivity he inhaled? Internal radiation is far more serious than external radiation, as his lungs are likely still being irradiated from the radioisotopes he breathed in during his short visit. |

|

Fukushima’s mothers became radiation experts to protect their children after nuclear meltdown

Key points:

- Mothers in Fukushima set up a radiation testing lab because they didn’t trust government results

- The women test food, water and soil and keep the public informed about radiation levels

- A major earthquake and tsunami caused a nuclear accident at the Fukushima power plant in 2011

They are testing everything — rice, vacuum cleaner dust, seafood, moss and soil — for toxic levels of radiation.

But these lab workers are not typical scientists.

They are ordinary mums who have built an extraordinary clinic.

“Our purpose is to protect children’s health and future,” says lab director Kaori Suzuki.

In March 2011, nuclear reactors catastrophically melted down at the Fukushima Daiichi plant, following an earthquake and tsunami.

Driven by a desperate need to keep their children safe, a group of mothers began testing food and water in the prefecture.

The women, who had no scientific background, built the lab from the ground up, learning everything on the job.

The lab is named Tarachine, a Japanese word which means “beautiful mother”.

“As mothers, we had to find out what we can feed our children and if the water was safe,” Ms Suzuki says.

“We had no choice but to measure the radiation and that’s why we started Tarachine.”

After the nuclear accident, Fukushima residents waited for radiation experts to arrive to help.

“No experts who knew about measuring radiation came to us. It was chaos,” she says.

In the days following the meltdown, a single decision by the Japanese Government triggered major distrust in official information which persists to this day.

The Government failed to quickly disclose the direction in which radioactive materials was drifting from the power plant.

Poor internal communications caused the delay, but the result was that thousands fled in the direction that radioactive materials were flying.

Former trade minister Banri Kaieda, who oversaw energy policy at the time, has said that he felt a “sense of shame” about the lack of disclosure.

But Kaori Suzuki said she still finds it difficult to trust the government.

“They lied and looked down on us, and a result, deceived the people,” Ms Suzuki says.

“So it’s hard for the people who experienced that to trust them.”

She and the other mothers who work part-time at the clinic feel great responsibility to protect the children of Fukushima.

But it hasn’t always been easy.

When they set up the lab, they relied on donated equipment, , and none of them had experience in radiation testing. There was nobody who could teach us and just the machines arrived,” Ms Suzuki says.

“At the time, the analysing software and the software with the machine was in English, so that made it even harder to understand.

“In the initial stage we struggled with English and started by listening to the explanation from the manufacturer. We finally got some Japanese software once we got started with using the machines.”

Radiation experts from top universities gave the mothers’ training, and their equipment is now among the most sophisticated in the country.

Food safety is still an issue

The Fukushima plant has now been stabilised and radiation has come down to levels considered safe in most areas.

But contamination of food from Japan remains a hotly contested issue.

Australia was one of the first countries to lift import restrictions on Japanese food imports after the disaster.

But more than 20 countries and trading blocs have kept their import ban or restrictions on Japanese fisheries and agricultural products.

At the clinic in Fukushima, Kaori Suzuki said she accepted that decision.

“It doesn’t mean it’s right or wrong. I feel that’s just the decision they have made for now,” she says.

Most results in their lab are comparatively low, but the mothers say it is important there is transparency so that people know what their children are consuming.

Fukushima’s children closely monitored after meltdown

Noriko Tanaka is one of many mothers in the region who felt that government officials were completely unprepared for the unfolding disaster.

She was three months pregnant with her son Haru when the disaster struck.

Ms Tanaka lived in Iwaki City, about 50 kilometres south of the power plant.

Amid an unfolding nuclear crisis, she panicked that the radioactive iodine released from the meltdown would harm her unborn child.

She fled on the night of the disaster.

When she returned home 10 days later, the fear of contamination from the invisible, odourless radioactive material weighed deeply on her mind.

“I wish I was able to breastfeed the baby,” she says.

“[Radioactive] caesium was detected in domestic powdered milk, so I had to buy powdered milk made overseas to feed him.”

Ms Tanaka now has two children —seven-year-old Haru and three-year-old Megu. She regularly takes them in for thyroid checks which are arranged free-of-charge by the mothers’ clinic.

Radiation exposure is a proven risk factor for thyroid cancer, but experts say it’s too early to tell what impact the nuclear meltdown will have on the children of Fukushima.

Noriko Tanaka is nervous as Haru’s thyroid is checked.

“In the last examination, the doctor said Haru had a lot of cysts, so I was very worried,” she says.

However this time, Haru’s results are better and he earns a high-five from Dr Yoshihiro Noso.

He said there was nothing to worry about, so I feel relieved after taking the test,” Ms Tanaka says.

“The doctor told me that the number of cysts will increase and decrease as he grows up.”

Doctor Noso has operated on only one child from Fukushima, but it is too early to tell if the number of thyroid cancers is increasing because of the meltdown.

“There isn’t a way to distinguish between cancers that were caused naturally and those by the accident,” he says.Dr Noso says his biggest concern is for children who were under five years old when the accident happened.The risk is particularly high for girls.

Even if I say there is nothing to worry medically, each mother is still worried,” he says.

“They feel this sense of responsibility because they let them play outside and drink the water. If they had proper knowledge of radiation, they would not have done that,” he said.

Mums and doctors fear for future of Fukushima’s children

After the Chernobyl nuclear disaster of 1986, the incidence of thyroid cancers increased suddenly after five years….

“In the case of Chernobyl, the thyroid cancer rate increased for about 10 years. It’s been eight years since the disaster and I would like to continue examinations for another two years.” …….

Some children, whose families fled Fukushima to other parts of Japan have faced relentless bullying.

“Some children who evacuated from Fukushima living in other prefectures are being bullied [so badly that they] can’t go to school,” Noriko Tanaka said.

“The radiation level is low in the area we live in and it’s about the same as Tokyo, but we will be treated the same as the people who live in high-level radiation areas.”

Noriko is particularly worried for little Megu because of prejudice against the children of Fukushima.

“For girls, there are concerns about marriage and having children because of the possibility of genetic issues.”

Radioactive fallout could be released from melting glaciers

“Anthropocene Nuclear Legacy” –Melting Glaciers Could Unleash Radioactive Fallout https://dailygalaxy.com/2019/05/anthropocene-nuclear-legacy-melting-glaciers-could-unleash-radioactive-fallout/ May 9, 2019 “These materials are a product of what we have put into the atmosphere. This is just showing that our nuclear legacy hasn’t disappeared yet. It’s still there,”said Caroline Clason, a lecturer in Physical Geography at the University of Plymouth of a study published in Nature that surveyed 19,000 of Earth’s glaciers and found their total melt amounts to a loss of 335 billion tons of ice each year, more than measurements of previous studies.“When it was built in the early 1900s, the road into Mount Rainier National Park from the west passed near the foot of the Nisqually Glacier, one of the mountain’s longest,” reports the New York Times. “Visitors could stop for ice cream at a stand built among the glacial boulders and gaze in awe at the ice. The ice cream stand (image below) is long gone.”

The glacier now ends more than a mile farther up the mountain, and they are melting elsewhere around the world too.

This scary scenario of our nuclear legacy was explored by an international team of scientists who studied the spread of radioactive contaminants in Arctic glaciers throughout Sweden, Iceland, Greenland, the Norwegian archipelago Svalbard, the European Alps, the Caucasus, British Columbia, and Antarctica. The researchers shared their results at the 2019 General Assembly of the European Geosciences Union (EGU) in Vienna.

It found man made radioactive material at all 17 survey sites, often at concentrations at least 10 times higher than levels elsewhere. “They are some of the highest levels you see in the environment outside nuclear exclusion zones,” said Caroline Clason

Fallout radionuclides (FRNs) were detected these sites. Radioactive material was found embedded within ice surface sediments called “cryoconite,” and at concentration levels ten times greater than the surrounding environment.“ They are some of the highest levels you see in the environment outside nuclear exclusion zones,” Clason, who led the research project, told AFP.

The Chernobyl disaster of 1986—by far the most devastating nuclear accident to date—released vast clouds of radioactive material including Caesium into the atmosphere, causing widespread contamination and acid rain across northern Europe for weeks afterwards. “Radioactive particles are very light so when they are taken up into the atmosphere they can be transported a very long way,” she told AFP. “When it falls as rain, like after Chernobyl, it washes away and it’s sort of a one-off event. But as snow, it stays in the ice for decades and as it melts in response to the climate it’s then washed downstream.”

The environmental impact of this has been shown in recent years, as wild boar meat in Sweden was found to contain more than 10 times the safe levels of Caesium.

“We’re talking about weapons testing from the 1950s and 1960s onwards, going right back in the development of the bomb,” Clason said. “If we take a sediment core you can see a clear spike where Chernobyl was, but you can also see quite a defined spike in around 1963 when there was a period of quite heavy weapons testing.”

Weapons tests can fling radioactive detritus up to 50 miles in the air. Smaller, lighter materials will travel into the upper atmosphere, and may “circulate around the world for years, or even decades, until they gradually settle out or are brought back to the surface by precipitation,” according to the Environmental Protection Agency.

Fallout is comprised of radionuclides such as Americium-241, Cesium-137, Iodine-131, and Strontium-90. Depending on a material’s half-life, it could remain in the environment minutes to years before decaying. Their levels of radiation also vary.

Particles can return to the immediate area as acid rain that’s absorbed by plants and soil, wreaking havoc on ecosystems, human health, and communities. But radionuclides that travel far and wide can settle in concentrated levels on snow and ice—large amounts of radioactive material from Fukushima was found in 2011 on four glaciers in the Tibetan Plateau, for example.

One of the most potentially hazardous residues of human nuclear activity is Americium, which is produced when Plutonium decays. Whereas Plutonium has a half-life of 14 years, Americium lasts 400.

Americium is more soluble in the environment and it is a stronger alpha (radiation) emitter. Both of those things are bad in terms of uptake into the food chain,” said Clason. While there is little data available on how these materials can be passed down the food chain—even potentially to humans—Clason said there was no doubt that Americium is “particularly dangerous”.

As geologists look for markers of the epoch when mankind directly impacted the health of the planet—known as the Anthropocene—Clason and her team believe that radioactive particles in ice, soil and sediment could be an important indicator.

The team hopes that future research will investigate how fallout could disperse into the food chain from glaciers, calling it a potential “secondary source of environmental contamination many years after the nuclear event of their origin.”

The Daily Galaxy via AFP, France24, and Nature

Deep ocean animals are eating radioactive carbon from nuclear bomb tests

|

By Kay Vandette , 10 May 19, A new study has revealed that even the most remote and deep regions on Earth are not isolated from human activities. According to the research, radioactive carbon leftover from nuclear bomb tests in the 1950s and 1960s has made its way to the bottom of the ocean. |

|

|

Deep ocean trenches found to have radioactive carbon from nuclear bomb tests

Radioactive carbon from nuclear bomb tests found in deep ocean trenches, Phys Org, by American Geophysical Union 8 May 19, Radioactive carbon released into the atmosphere from 20th-century nuclear bomb tests has reached the deepest parts of the ocean, new research finds.A new study in AGU’s journal Geophysical Research Letters finds the first evidence of radioactive carbon from nuclear bomb tests in muscle tissues of crustaceans that inhabit Earth’s ocean trenches, including the Mariana Trench, home to the deepest spot in the ocean. Radioactive carbon from nuclear bomb tests found in deep ocean trenches, Phys Org, by American Geophysical Union 8 May 19, Radioactive carbon released into the atmosphere from 20th-century nuclear bomb tests has reached the deepest parts of the ocean, new research finds.A new study in AGU’s journal Geophysical Research Letters finds the first evidence of radioactive carbon from nuclear bomb tests in muscle tissues of crustaceans that inhabit Earth’s ocean trenches, including the Mariana Trench, home to the deepest spot in the ocean.

Organisms at the ocean surface have incorporated this “bomb carbon” into the molecules that make up their bodies since the late 1950s. The new study finds crustaceans in deep ocean trenches are feeding on organic matter from these organisms when it falls to the ocean floor. The results show human pollution can quickly enter the food web and make its way to the deep ocean, according to the study’s authors. “Although the oceanic circulation takes hundreds of years to bring water containing bomb [carbon] to the deepest trench, the food chain achieves this much faster,” said Ning Wang, a geochemist at the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Guangzhou, China, and lead author of the new study. “There’s a very strong interaction between the surface and the bottom, in terms of biologic systems, and human activities can affect the biosystems even down to 11,000 meters, so we need to be careful about our future behaviors,” said Weidong Sun, a geochemist at the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Qingdao, China, and co-author of the new study. “It’s not expected, but it’s understandable, because it’s controlled by the food chain.”…… Thermonuclear weapons tests conducted during the 1950s and 1960s doubled the amount of carbon-14 in the atmosphere when neutrons released from the bombs reacted with nitrogen in the air. Levels of this “bomb carbon” peaked in the mid-1960s and then dropped when atmospheric nuclear tests stopped. By the 1990s, carbon-14 levels in the atmosphere had dropped to about 20 percent above their pre-test levels. This bomb carbon quickly fell out of the atmosphere and mixed into the ocean surface. Marine organisms that have lived in the decades since this time have used bomb carbon to build molecules within their cells, and scientists have seen elevated levels of carbon-14 in marine organisms since shortly after the bomb tests began……..https://phys.org/news/2019-05-radioactive-carbon-nuclear-deep-ocean.html |

|

|

Climate Change Could Unleash Long-Frozen Radiation

https://www.popularmechanics.com/science/environment/a27150094/climate-change-could-unleash-long-frozen-radiation/

https://www.popularmechanics.com/science/environment/a27150094/climate-change-could-unleash-long-frozen-radiation/

Atomic bombs, Chernobyl,Fukushima—radiation has traveled and frozen all over the world. Global warming is changing that.

Melting could be one of the most important phenomena of the 21st century. Thanks to man-made climate change, Arctic ice levels have hit a record low this year. Among the many profound changes that could stem from ice melting across the world, according to a new study from an international group of scientists, is the release of deeply buried radiation.

The international team studied 17 icy locations across the globe, including the Arctic, the Antarctic, Iceland, the Alps, the Caucasus mountains, and British Columbia. While radiation exists naturally, the scientists were looking for example of human-made radiation. It was common to find concentrations at least 10 times higher than levels elsewhere.

“They are some of the highest levels you see in the environment outside nuclear exclusion zones,” says Caroline Clason, a lecturer in Physical Geography at the University of Plymouth, speaking in a press statement.

When human-made radiation is released into the environment, be it in small amounts like the Three Mile Island accident of 1979 or larger quantities like the Chernobyl disaster of 1986and the Fukushima Daichii accident of 2011, it goes into the atmosphere. That includes elements like radioactive cesium, which have been known to make people sick to the point of death across the globe.

After Chernobyl, clouds of cesium traveled across Europe. Radiation spread without regard for borders, reaching as far as England through rains. But when rain freezes, it takes the form of ice. And within ice, it can lay trapped.

“Radioactive particles are very light so when they are taken up into the atmosphere they can be transported a very long way,” Clason tells the AFP. “When it falls as rain, like after Chernobyl, it washes away and it’s sort of a one-off event. But as snow, it stays in the ice for decades and as it melts in response to the climate it’s then washed downstream.”

What does that response look like? Humanity is starting to find out, Clason says. She points to wild boar in Sweden, who in 2017 were found to have 10 times the levels of normal radiation.

Traces of human-made radiation last a famously long time. Ice around the globe contains nuclear material not just from accidents involving nuclear power plants, but also man’s use of nuclear weapons.

“We’re talking about weapons testing from the 1950s and 1960s onwards, going right back in the development of the bomb,” Clason says. “If we take a sediment core you can see a clear spike where Chernobyl was, but you can also see quite a defined spike in around 1963 when there was a period of quite heavy weapons testing.”

Elements within radiation have different life spans. Perhaps the most notorious of these, Plutonium-241 has a 14 year half-life. [ed. most plutonium isotopes have half-lives of many thousands of years] But Americium-241, a synthetic chemical element, has a half life of 432 years. It can stay in ice a long time, and when that ice melts will spread. There isn’t much data yet on its ability to spread into the human food chain, but Clason called the threat of Americum “particularly dangerous”.

A term popular in science these days is the Anthropocene, which refers to the idea that humans have permanently altered the very core of how the Earth functions as a living ecosystem. Looking for radiation buried within icy soil and sediment could offer stronger proof of those changes.

“These materials are a product of what we have put into the atmosphere. This is just showing that our nuclear legacy hasn’t disappeared yet, it’s still there,” she says.

“And it’s important to study that because ultimately it’s a mark of what we have left in the environment.”

The Chernobyl Syndrome

With bountiful, devastating detail, Brown describes how scientists, doctors, and journalists—mainly in Ukraine and Belarus—went to great lengths and took substantial risks to collect information on the long-term effects of the Chernobyl explosion, which they believed to be extensive.

Other researchers have issued a much sunnier picture of post-Chernobyl ecology, but Brown argues persuasively that they are grossly underestimating the scale of the damage, in part because they rely too heavily on simplistic measurements of radioactivity levels.

Radiation has a special hold on our imagination: an invisible force out of science fiction, it can alter the very essence of our bodies, dissolve us from the inside out. But Manual for Survival asks a larger question about how humans will coexist with the ever-increasing quantities of toxins and pollutants that we introduce into our air, water, and soil. Brown’s careful mapping of the path isotopes take is highly relevant to other industrial toxins, and to plastic waste. When we put a substance into our environment, we have to understand that it will likely remain with us for a very long time, and that it may behave in ways we never anticipated. Chernobyl should not be seen as an isolated accident or as a unique disaster, Brown argues, but as an “exclamation point” that draws our attention to the new world we are creating.

The Chernobyl Syndrome, The New York Review of Books SophiePinkham, APRIL4, 2019

Manual for Survival: A Chernobyl Guide to the Futur e

e

Midnight in Chernobyl: The Untold Story of the World’s Greatest Nuclear Disaster

Chernobyl: The History of a Nuclear Catastrophe

“………As her book’s title, Manual for Survival, suggests, Kate Brown is interested in the aftermath of Chernobyl, not the disaster itself. Her heroes are not first responders but brave citizen-scientists, independent-minded doctors and health officials, journalists, and activists who fought doggedly to uncover the truth about the long-term damage caused by Chernobyl. Her villains include not only the lying, negligent Soviet authorities, but also the Western governments and international agencies that, in her account, have worked for decades to downplay or actually conceal the human and ecological cost of nuclear war, nuclear tests, and nuclear accidents. Rather than attributing Chernobyl to authoritarianism, she points to similarities in the willingness of Soviets and capitalists to sacrifice the health of workers, the public, and the environment to production goals and geopolitical rivalries. Continue reading

Ionising radiation released from ice surface sediments, as climate change melts glaciers

Siren sounds on nuclear fallout embedded in melting glaciers https://phys.org/news/2019-04-siren-nuclear-fallout-embedded-glaciers.html, by Patrick Galey, 10 Apr 19, Radioactive fallout from nuclear meltdowns and weapons testing is nestled in glaciers across the world, scientists said Wednesday, warning of a potentially hazardous time bomb as rising temperatures melt the icy residue.

Siren sounds on nuclear fallout embedded in melting glaciers https://phys.org/news/2019-04-siren-nuclear-fallout-embedded-glaciers.html, by Patrick Galey, 10 Apr 19, Radioactive fallout from nuclear meltdowns and weapons testing is nestled in glaciers across the world, scientists said Wednesday, warning of a potentially hazardous time bomb as rising temperatures melt the icy residue.

For the first time, an international team of scientists has studied the presence of nuclear fallout in ice surface sediments on glaciers across the Arctic, Iceland the Alps, Caucasus mountains, British Columbia and Antarctica.

It found manmade radioactive material at all 17 survey sites, often at concentrations at least 10 times higher than levels elsewhere.

“They are some of the highest levels you see in the environment outside nuclear exclusion zones,” said Caroline Clason, a lecturer in Physical Geography at the University of Plymouth.

When radioactive material is released into the atmosphere, it falls to earth as acid rain, some of which is absorbed by plants and soil.

But when it falls as snow and settles in the ice, it forms heavier sediment which collects in glaciers, concentrating the levels of nuclear residue.

The Chernobyl disaster of 1986—by far the most devastating nuclear accident to date—released vast clouds of radioactive material including Caesium into the atmosphere, causing widespread contamination and acid rain across northern Europe for weeks afterwards.

“Radioactive particles are very light so when they are taken up into the atmosphere they can be transported a very long way,” she told AFP.

“When it falls as rain, like after Chernobyl, it washes away and it’s sort of a one-off event. But as snow, it stays in the ice for decades and as it melts in response to the climate it’s then washed downstream.”

The environmental impact of this has been shown in recent years, as wild boar meat in Sweden was found to contain more than 10 times the safe levels of Caesium.

Clason said her team had detected some fallout from the Fukushima meltdown in 2011, but stressed that much of the particles from that particular disaster had yet to collect on the ice sediment.

As well as disasters, radioactive material produced from weapons testing was also detected at several research sites.

“We’re talking about weapons testing from the 1950s and 1960s onwards, going right back in the development of the bomb,” she said. “If we take a sediment core you can see a clear spike where Chernobyl was, but you can also see quite a defined spike in around 1963 when there was a period of quite heavy weapons testing.”

One of the most potentially hazardous residues of human nuclear activity is Americium, which is produced when Plutonium decays.

Whereas Plutonium has a half-life of 14 years, Americium lasts 400. [Ed note: Most plutonium isotopes have very long half-lives, plutonium-239 being one of the shortest at over 24,000 years]

“Americium is more soluble in the environment and it is a stronger alpha (radiation) emitter. Both of those things are bad in terms of uptake into the food chain,” said Clason.

While there is little data available on how these materials can be passed down the food chain—even potentially to humans—Clason said there was no doubt that Americium is “particularly dangerous”.

As geologists look for markers of the epoch when mankind directly impacted the health of the planet—known as the Anthropocene—Clason and her team believe that radioactive particles in ice, soil and sediment could be an important indicator.

“These materials are a product of what we have put into the atmosphere. This is just showing that our nuclear legacy hasn’t disappeared yet, it’s still there,” Clason said.

“And it’s important to study that because ultimately it’s a mark of what we have left in the environment.”

Before we enter “a new nuclear age” – learn from the newly declassified Chernobyl health records

Fortunately, Chernobyl health records are now available to the public. They show that people living in the radioactive traces fell ill from cancers, respiratory illness, anaemia, auto-immune disorders, birth defects, and fertility problems two to three times more frequently in the years after the accident than before. In a highly contaminated Belarusian town of Veprin, just six of 70 children in 1990 were characterised as “healthy”. The rest had one chronic disease or another. On average, the Veprin children had in their bodies 8,498 bq/kg of radioactive caesium (20 bq/kg is considered safe).

Fortunately, Chernobyl health records are now available to the public. They show that people living in the radioactive traces fell ill from cancers, respiratory illness, anaemia, auto-immune disorders, birth defects, and fertility problems two to three times more frequently in the years after the accident than before. In a highly contaminated Belarusian town of Veprin, just six of 70 children in 1990 were characterised as “healthy”. The rest had one chronic disease or another. On average, the Veprin children had in their bodies 8,498 bq/kg of radioactive caesium (20 bq/kg is considered safe).

For decades, researchers have puzzled over strange clusters of thyroid cancer, leukaemia and birth defects among people living in Cumbria, which, like southern Belarus, is an overlooked hotspot of radioactivity from cold war decades of nuclear bomb production and nuclear power accidents.

Currently, policymakers are advocating a massive expansion of nuclear power as a way to combat climate change. Before we enter a new nuclear age, the declassified Chernobyl health records raise questions that have been left unanswered about the impact of chronic low doses of radioactivity on human health.

*******************************************************

As researchers monitored Chernobyl radioactivity, they made a troubling discovery. Only half of the caesium-137 they detected came from Chernobyl. The rest had already been in the Cumbrian soils; deposited there during the years of nuclear testing and after the 1957 fire at the Windscale plutonium plant. The same winds and rains that brought down Chernobyl fallout had been at work quietly distributing radioactive contaminants across northern England and Scotland for decades. Fallout from bomb tests carried out during the cold war scattered a volume of radioactive gases that dwarfed Chernobyl.

The Chernobyl explosions issued 45m curies of radioactive iodine into the atmosphere. Emissions from Soviet and US bomb tests amounted to 20bn curies of radioactive iodine, 500 times more. Radioactive iodine, a short lived, powerful isotope can cause thyroid disease, thyroid cancer, hormonal imbalances, problems with the GI tract and autoimmune disorders.

As engineers detonated over 2,000 nuclear bombs into the atmosphere, scientists lost track of where radioactive isotopes fell and where they came from, but they caught glimpses of how readily radioactivity travelled the globe.

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2019/apr/04/chernobyl-nuclear-power-climate-change-health-radioactivity, So that day, in a Moscow airport, technicians loaded artillery shells with silver iodide. Soviet air force pilots climbed into the cockpits of TU-16 bombers and made the easy one-hour flight to Chernobyl, where the reactor burned. The pilots circled, following the weather. They flew 30, 70, 100, 200km – chasing the inky black billows of radioactive waste. When they caught up with a cloud, they shot jets of silver iodide into it to emancipate the rain.In the sleepy towns of southern Belarus, villagers looked up to see planes with strange yellow and grey contrails snaking across the sky. Next day, 27 April, powerful winds kicked up, cumulus clouds billowed on the horizon, and rain poured down in a deluge. The raindrops scavenged radioactive dust floating 200 metres in the air and sent it to the ground. The pilots trailed the slow-moving gaseous bulk of nuclear waste north-east beyond Gomel, into Mogilev province. Wherever pilots shot silver iodide, rain fell, along with a toxic brew of a dozen radioactive elements.

If Operation Cyclone had not been top secret, the headline would have been spectacular: “Scientists using advanced technology save Russian cities from technological disaster!” Yet, as the old saying goes, what goes up must come down. No one told the Belarusians that the southern half of the republic had been sacrificed to protect Russian cities. In the path of the artificially induced rain lived several hundred thousand Belarusians ignorant of the contaminants around them.

The public is often led to believe that the Chernobyl exclusion zone, a depopulated 20-mile circle around the blown plant, safely contains Chernobyl radioactivity. Tourists and journalists exploring the zone rarely realise there is a second Chernobyl zone in southern Belarus. In it, people lived for 15 years in levels of contamination as high as areas within the official zone until the area was finally abandoned, in 1999.

In believing that the Chernobyl zone safely contained the accident, we fall for the proximity trap, which holds that the closer a person is to a nuclear explosion, the more radioactivity they are exposed to. But radioactive gases follow weather patterns, moving around the globe to leave shadows of contamination in shapes that resemble tongues, kidneys, or the sharp tips of arrows.

Research on gene mutations caused by nuclear radiation – Kazakhstan

Over the years, those who sought care from Dispensary No. 4 or the IRME were logged in the state’s medical registry, which tracks the health of people exposed to the Polygon tests. People are grouped by generation and by how much radiation they received, on the basis of where they lived. Although the registry does not include every person who was affected, at one point it listed more than 351,000 individuals across 3 generations. More than one-third of these have died, and many others have migrated or lost contact. But according to Muldagaliev, about 10,000 people have been continually observed since 1962. Researchers consider the registry an important and relatively unexplored resource for understanding the effects of long-term and low-dose radiation2.

Over the years, those who sought care from Dispensary No. 4 or the IRME were logged in the state’s medical registry, which tracks the health of people exposed to the Polygon tests. People are grouped by generation and by how much radiation they received, on the basis of where they lived. Although the registry does not include every person who was affected, at one point it listed more than 351,000 individuals across 3 generations. More than one-third of these have died, and many others have migrated or lost contact. But according to Muldagaliev, about 10,000 people have been continually observed since 1962. Researchers consider the registry an important and relatively unexplored resource for understanding the effects of long-term and low-dose radiation2.

Geneticists have been able to use these remaining records to investigate the generational effects of radiation…….

In 2002, Dubrova and his colleagues reported that the mutation rate in the germ lines of those who had been directly exposed was nearly twice that found in controls3. The effects continued in subsequent generations that had not been directly exposed to the blasts. Their children had a 50% higher rate of germline mutation than controls had. Dubrova thinks that if researchers can establish the pattern of mutation in the offspring of irradiated parents, then there could be a way to predict the long-term, intergenerational health risks.

The nuclear sins of the Soviet Union live on in Kazakhstan https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-019-01034-8 – 3 Apr 19, Decades after weapons testing stopped, researchers are still struggling to decipher the health impacts of radiation exposure around Semipalatinsk. The statues of Lenin are weathered and some are tagged with graffiti, but they still stand tall in the parks of Semey, a small industrial city tucked in the northeast steppe of Kazakhstan. All around the city, boxy Soviet-era cars and buses lurch past tall brick apartment buildings and cracked walkways, relics of a previous regime.Other traces of the past are harder to see. Folded into the city’s history — into the very DNA of its people — is the legacy of the cold war. The Semipalatinsk Test Site, about 150 kilometres west of Semey, was the anvil on which the Soviet Union forged its nuclear arsenal. Between 1949 and 1963, the Soviets pounded an 18,500-square-kilometre patch of land known as the Polygon with more than 110 above-ground nuclear tests. Kazakh health authorities estimate that up to 1.5 million people were exposed to fallout in the process. Underground tests continued until 1989.

Much of what’s known about the health impacts of radiation comes from studies of acute exposure — for example, the atomic blasts that levelled Hiroshima and Nagasaki in Japan or the nuclear disaster at Chernobyl in Ukraine. Studies of those events provided grim lessons on the effects of high-level exposure, as well as the lingering impacts on the environment and people who were exposed. Such work, however, has found little evidence that the health effects are passed on across generations.

People living near the Polygon were exposed not only to acute bursts, but also to low doses of radiation over the course of decades (see ‘Danger on the wind’). Kazakh researchers have been collecting data on those who lived through the detonations, as well as their children and their children’s children. Continue reading

Why Low dose radiation can be more dangerous- more cancers per person than at high doses

LeRoy Moore: Low-dose radiation can be more dangerous, http://www.dailycamera.com/letters/ci_32543151/leroy-moore-low-dose-radiation-can-be-more 31 Mar 19 Though Maddie Nagle’s beautifully written column of March 8 criticizes me, more important is that she downplays the significance of low-dose exposure to the alpha radiation of plutonium at Rocky Flats. This could harm people unaware of the danger. Carl Morgan, the “Father of Health Physics,” studied the effects of radiation for those building Manhattan Project nuclear weapons. He knew that the alpha particles released by plutonium cannot be harmful unless inhaled or taken into the body through an open wound.

LeRoy Moore: Low-dose radiation can be more dangerous, http://www.dailycamera.com/letters/ci_32543151/leroy-moore-low-dose-radiation-can-be-more 31 Mar 19 Though Maddie Nagle’s beautifully written column of March 8 criticizes me, more important is that she downplays the significance of low-dose exposure to the alpha radiation of plutonium at Rocky Flats. This could harm people unaware of the danger. Carl Morgan, the “Father of Health Physics,” studied the effects of radiation for those building Manhattan Project nuclear weapons. He knew that the alpha particles released by plutonium cannot be harmful unless inhaled or taken into the body through an open wound.

Toward the end of his life he spoke to Robert Del Tredici. He said “down at the low doses you actually get more cancers per person rem than you do at the high doses … because the high levels will often kill cells outright, whereas the low levels of exposure tend to injure cells rather than kill them and it is the surviving injured cells that are the cause for concern.” The effects of a small exposure “will be much more severe than had been anticipated.”(Del Tredici, “At Work in the Fields of the Bomb,” 1987, p. 133)

Nagle also makes misleading remarks about Tom K. Hei of Columbia University. Hei and colleagues demonstrated that a single plutonium alpha particle induces mutations in mammal cells. Cells receiving very low doses are more likely to be damaged than destroyed. Replication of these damaged cells constitutes genetic harm, and more such harm per unit dose occurs at very low doses than would occur with higher dose exposures. “These data provide direct evidence that a single alpha particle traversing a nucleus will have a high probability of resulting in a mutation and highlight the need for radiation protection at low doses.” (Hei et al., Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 94, April 1997, pp. 3765-3770.)

Age and Sex Bias in Radiation Research

|

Age and Sex Bias in Radiation Research—and How to Overcome It http://jnm.snmjournals.org/content/60/4/466.full, 1 Apr 19, Britta Langen, Department of Radiation Physics, Institute of Clinical Sciences, Sahlgrenska Cancer Center, Sahlgrenska Academy, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden

Basic research is the driving force behind medical progress. As successful as this relation has been, an intrinsic dilemma persists to this day: each study design frames reality—yet the conclusions seek general validity. This dilemma crystallizes into major bias when conclusions are based on selected groups that do not represent the reality of biologic diversity. Ironically, while striving for a future of highly personalized treatments, we have overlooked the obvious features that make an individual, stratify a cohort, and influence outcome: age and sex. A current example of this issue are molecular biomarkers that may bring the next quantum leap in clinical practice. Biomarkers such as transcripts, proteins, or metabolites can easily be sampled from blood, quantified, and used for biologic dosimetry, risk estimation for postradiation therapy diseases, or screening in radiation hazard events. Still, most studies that use novel “omics” or “next-gen” methods for screening harbor pitfalls similar to previous methodologies and neglect age and sex as important factors. This can compromise the sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy of biomarkers, leading to erroneous diagnosis and treatment planning. Sex bias in biomedical research is not a new revelation (1). Surprisingly, it stems not only from the use of single-sex cohorts but also from omitting sex as a factor altogether. Although other fields, such as neuroscience research, have started to tackle this issue (2), it remains largely unaddressed and underrepresented in radiation biology and related medical fields. For instance, sex-specific radiation sensitivity is known in principle yet is rarely considered in study designs beyond this particular research question. The bias in our knowledge base becomes even more worrisome when considering the nonlinearity of age between humans and mice (3). Do we relate age according to sexual maturity, onset of senescence, or total life span? It is reasonable to assume that the answer is, “depending on the research question and biologic endpoint.” However, this issue is usually neglected altogether and the age of the animal is chosen for purely practical reasons. Recently, research on age and sex bias has shown that radiation responses can differ largely between male and female mice, as well as between adolescent and adult specimens (4). If only one group had been used in the proteomic screening for blood-based biomarkers, the conclusions on dose–response would differ and poorly represent radiobiologic effects for other sex and age groups. Most importantly: if neglected, the bias would remain unknown and create large uncertainties that ultimately lead to avoidable risks for patients in radiotherapy and nuclear medicine. It will be difficult to update our knowledge base to consider these basic factors systematically; in the end, a large body of evidence will still include age and sex biases. Nevertheless, the sooner we start taking action to overcome age and sex bias in our field, the less will misleading information contaminate the knowledge base. Each of us can partake in this effort according to our opportunities. For example, researchers can plan studies with male and female cohorts, principal investigators can establish such cohorts as the group standard, and manuscripts and grant applications can address these possible biases and highlight measures on how to control them. Reviewers can identify age and sex bias and consider it a methodologic limitation, and editors can establish submission forms that require disclosure of age and sex as preclinical study parameters. Lecturers can inform about these potential biases in research and raise students’ awareness when working with source material. Finally, students and PhD candidates can take initiative and, if presented with biased data or methodologies, address age and sex as important factors. Undoubtedly, using both male and female cohorts and different age groups in research is resource-intensive. It is paramount that funding agencies support these efforts by rewarding points for rigorous research designs that consider age and sex as essential factors. Some large international funding agencies have already started to include dedicated sections on the age and sex dimension in grant applications, but this change needs to be consistent across all funding bodies on the national and regional levels. By committing to a higher methodologic standard, we can reduce critical bias in our field and in radiation research as a whole. Ultimately, our effort will increase the quality of diagnosis and treatment and improve the odds for therapeutic success for every patient. |

|

|

-

Archives

- January 2026 (246)

- December 2025 (358)

- November 2025 (359)

- October 2025 (376)

- September 2025 (258)

- August 2025 (319)

- July 2025 (230)

- June 2025 (348)

- May 2025 (261)

- April 2025 (305)

- March 2025 (319)

- February 2025 (234)

-

Categories

- 1

- 1 NUCLEAR ISSUES

- business and costs

- climate change

- culture and arts

- ENERGY

- environment

- health

- history

- indigenous issues

- Legal

- marketing of nuclear

- media

- opposition to nuclear

- PERSONAL STORIES

- politics

- politics international

- Religion and ethics

- safety

- secrets,lies and civil liberties

- spinbuster

- technology

- Uranium

- wastes

- weapons and war

- Women

- 2 WORLD

- ACTION

- AFRICA

- Atrocities

- AUSTRALIA

- Christina's notes

- Christina's themes

- culture and arts

- Events

- Fuk 2022

- Fuk 2023

- Fukushima 2017

- Fukushima 2018

- fukushima 2019

- Fukushima 2020

- Fukushima 2021

- general

- global warming

- Humour (God we need it)

- Nuclear

- RARE EARTHS

- Reference

- resources – print

- Resources -audiovicual

- Weekly Newsletter

- World

- World Nuclear

- YouTube

-

RSS

Entries RSS

Comments RSS