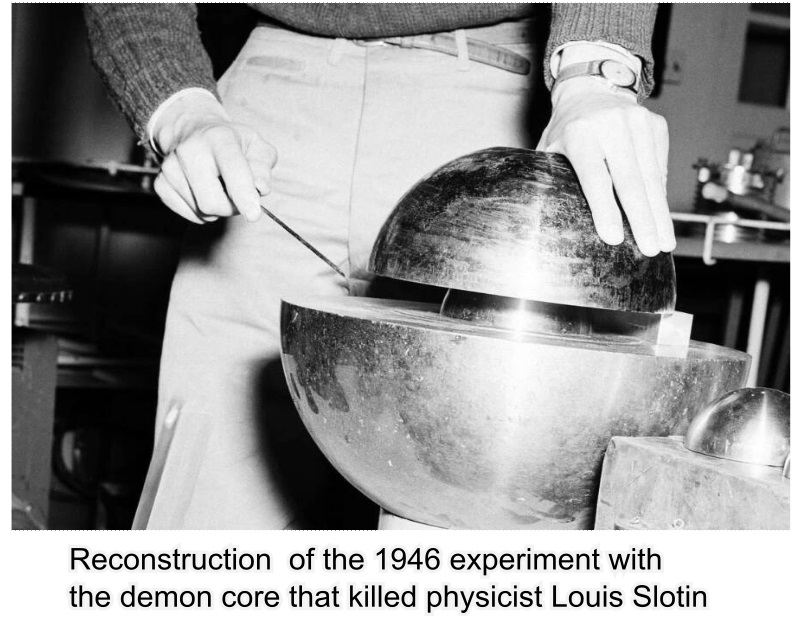

The ‘Demon Core,’ The 14-Pound Plutonium Sphere That Killed Two Scientists

By Kaleena Fraga | Checked By Erik Hawkins https://allthatsinteresting.com/demon-core December 10, 2022

Physicists Harry Daghlian and Louis Slotin both suffered agonizing deaths after making minor slips of the hand while working on the plutonium orb known as the “demon core” at Los Alamos Laboratory in New Mexico.

To survivors of the nuclear attacks in Hiroshima and Nagasaki during World War II, the nuclear explosions seemed like hell on earth. And though a third plutonium core — meant for use if Japan didn’t surrender — was never dropped, it still managed to kill two scientists. The odd circumstances of their deaths led the core to be nicknamed “demon core.”

Retired to the Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico following the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagaski, demon core killed two scientists exactly nine months apart. Both were conducting similar experiments on the core, and both made eerily similar mistakes that proved fatal.

Before the experiments, scientists had called the core “Rufus.” After the deaths of their colleagues, the core was nicknamed “demon core.” So what exactly happened to the two scientists who died while handling it?

The Heart Of A Nuclear Bomb

In the waning days of World War II, the United States dropped two nuclear bombs on Japan. One fell on Hiroshima on Aug. 6, 1945, and one fell on Nagasaki on August 9. In case Japan didn’t surrender, the U.S. was prepared to drop a third bomb, powered by the plutonium core later called “demon core.”

The core was codenamed “Rufus.” It weighed almost 14 pounds and stretched about 3.5 inches in diameter. And when Japan announced its intention to surrender on August 15, scientists at the Los Alamos National Laboratory were allowed to keep the core for experiments.

As Atlas Obscura explains, the scientists wanted to test the limits of nuclear material. They knew that a nuclear bomb’s core went critical during a nuclear explosion, and wanted to better understand the limit between subcritical material and the much more dangerous radioactive critical state.

But such criticality experiments were dangerous — so dangerous that a physicist named Richard Feynman compared them to provoking a dangerous beast. He quipped in 1944 that the experiments were “like tickling the tail of a sleeping dragon.”

And like an angry dragon roused from slumber, demon core would soon kill two scientists at the Los Alamos National Laboratory when they got too close.

How Demon Core Killed Two Scientists

On Aug. 21, 1945, about a week after Japan expressed its intention to surrender, Los Alamos physicist Harry Daghlian conducted a criticality experiment on demon core that would cost him his life. According to Science Alert, he ignored safety protocols and entered the lab alone — accompanied only by a security guard — and got to work.

Daghlian’s experiment involved surrounding the demon core with bricks made of tungsten carbide, which created a sort of boomerang effect for the neutrons shed by the core itself. Daghlian brought the demon core right to the edge of supercriticality but as he tried to remove one of the bricks, he accidentally dropped it on the plutonium sphere. It went supercritical and blasted him with neutron radiation.

Daghlian died 25 days later. Before his death, the physicist suffered from a burnt and blistered hand, nausea, and pain. He eventually fell into a coma and passed away at the age of 24.

Exactly nine months later, on May 21, 1946, demon core struck again. This time, Canadian physicist Louis Slotin was conducting a similar experiment in which he lowered a beryllium dome over the core to push it toward supercriticality. To ensure that the dome never entirely covered the core, Slotin used a screwdriver to maintain a small opening though, Slotin had been warned about his method before.

But just like the tungsten carbide brick that had slipped out of Daghlian’s hand, Slotin’s screwdriver slipped out of his grip. The dome dropped and as the neutrons bounced back and forth, demon core went supercritical. Blue light and heat consumed Slotin and the seven other people in the lab.

“The blue flash was clearly visible in the room although it (the room) was well illuminated from the windows and possibly the overhead lights,” one of Slotin colleagues, Raemer Schreiber, recalled to the New Yorker. “The total duration of the flash could not have been more than a few tenths of a second. Slotin reacted very quickly in flipping the tamper piece off.”

Slotin may have reacted quickly, but he’d seen what happened to Daghlian. “Well,” he said, according to Schreiber, “that does it.”

Though the other people in the lab survived, Slotin had been doused with a fatal dose of radiation. The physicist’s hand turned blue and blistered, his white blood count plummeted, he suffered from nausea and abdominal pain, and internal radiation burns, and gradually become mentally confused. Nine days later, Slotin died at the age of 35.

Eerily, the core had killed both Daghlian and Slotin in similar ways. Both fatal incidences took place on a Tuesday, on the 21st of a month. Daghlian and Slotin even died in the same hospital room. Thus the core, previously codenamed “Rufus,” was nicknamed “demon core.”

What Happened To Demon Core?

Harry Daghlian and Louis Slotin’s deaths would forever change how scientists interacted with radioactive material. “Hands-on” experiments like the physicists had conducted were promptly banned. From that point on, researchers would handle radioactive material from a distance with remote controls.

So what happened to demon core, the unused heart of the third atomic bomb?

Researchers at Los Alamos National Laboratory had planned to send it to Bikini Atoll, in the Marshall Islands, where it would have been publicly detonated. But the core needed time to cool off after Slotin’s experiment, and when the third test at Bikini Atoll was canceled, plans for demon core changed.

After that, in the summer of 1946, the plutonium core was melted down to be used in the U.S. nuclear stockpile. Since the United States hasn’t, to date, dropped any more nuclear weapons, demon core remains unused.

But it retains a harrowing legacy. Not only was demon core meant to power a third nuclear weapon — a weapon destined to rain destruction and death on Japan — but it also killed two scientists who handled it in similar ways.

US military atomic cleanup crews were sent out in the wake of American nuclear testing, and many paid a heavy price, veterans say

“We’re still fighting. We’re not gonna give up, and we’re just gonna keep going and keep fighting,” Brownell said. “The world needs to know. They need to know how dangerous the radiation is — how dangerous nuclear testing is.”

https://www.businessinsider.com/us-military-atomic-cleanup-crews-heavy-price-nuclear-testing-2022-12 Jake Epstein , Dec 11, 2022

- Over a period of more than a decade, the US military conducted dozens of nuclear tests in the Pacific.

- Years later, soldiers were sent to the Marshall Islands to try and clean up the fallout from the testing.

- But many were exposed to contaminated food and dust, leaving them with severe and lasting health issues.

For over a decade beginning not long after World War II, the US carried out dozens of nuclear weapons tests in the Marshall Islands — a chain of islands and atolls in the middle of the Pacific Ocean.

The largest of the 67 tests that were conducted between 1946 and 1958 was Castle Bravo. On March 1, 1954, the US military detonated a thermonuclear weapon at Bikini Atoll, producing an explosive yield 1,000 times greater than the atomic bomb that devastated Hiroshima, Japan.

Nuclear tests like Castle Bravo produced a substantial amount of nuclear fallout that negatively affected the people of the Marshall Islands, according to the Brookings Institution think tank. Radioactive material was even found in communities thousands of miles away.2

‘There’s no way possibly to clean that up’

Ken Brownell, who was a carpenter when he served in the military in the late 1970s, was sent to the Marshall Islands in 1977 to build a base camp for hundreds of soldiers assigned to cleanup operations. These cleanup efforts involved a concrete dome that was built on Runit Island, one of 40 islands that make up Enewetak Atoll, which was used to deposit soil and debris contaminated by radiation.

The goal, Brownell said, was supposedly to make the area habitable again for the Marshallese people after all the nuclear testing that happened during the US occupation, which began during World War II (the Marshall Islands eventually became independent in 1979).

Brownell, 66, said he worked 12-hour work days, six days a week, while living on Lojwa — an island “deemed safe” at the time because it didn’t host any nuclear tests, even though it was located near islands that did. His job included excavations and pouring concrete.

But despite the US military’s efforts to clean up the islands, Brownell said there was one, massive problem — it just couldn’t be done.

“There’s no way possibly to clean that up. Once that soil was contaminated, the animals that lived on the islands, the birds, the rats, the coconut crabs, all the — whatever wildlife was there — they consumed all that,” Brownell said. “So all this — the radioactive material goes into the ocean, gets into the coral. Now you’ve got it into the fish life. You’ve got it into the lobsters.”

Brownell said exposure to radioactive material could come from “any place on those islands,” whether it was eating contaminated seafood, or just walking around in the dirt and breathing in contaminated dust.

“On our end of it, most of our guys are dead because of the cancers and all the ailments that come along with the radioactive materials that we ingested,” Brownell said, adding that he had nothing in the way of protective gear. On a typical day, he said he would wear an outfit consisting of just combat boots, shorts, and a hat.

Coming from a farming community in New York, Brownell said he had no knowledge of radioactive materials before getting sent to the Marshall Islands. He also said he didn’t receive any prior training in radiological cleanups and that the potential dangers of the mission were never properly addressed beforehand.

“There was no running water … you couldn’t actually wash up. So you’re eating a baloney sandwich with dirty, contaminated hands, sitting in contaminated soil,” Brownell said. “The government said, ‘Oh, don’t worry about it … be careful swimming because there’s sharks out there.'”

Atomic veteran Francis Lincoln Grahlfs echoed Brownell’s remarks about a lack of knowledge on the dangers of nuclear cleanups, writing in a Military Times op-ed last year that “little was known by the public about the long-term effects of radiation exposure.”

Impact of radiation contamination

Nuclear weapons testing in the Marshall Islands had “devastating effects” on the country’s environment that “remain unresolved,” according to a 2019 report by the Republic of the Marshall Islands’ National Nuclear Commission. Some individuals still “live with a daily fear of how their health might be affected by long-term exposure to radiation.”

Several of Brownell’s friends dealt with health complications that he believed to be related to their service in the Marshall Islands — and he was not immune. In 2001, he was diagnosed with stage-four non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and given only six months to live. That wasn’t the end though.

That six months has turned into 20 years — 21 years,” Brownell said. “So I’m grateful every day that I’m still here.”

Like Brownell, Grahlfs — who was sent to the Marshal Islands in 1946 — wrote in his December 2021 op-ed that he has suffered from health complications, including cancer, believed to be a result of his service.

Brownell and other veterans have been fighting to be covered by government services that could provide compensation and other care. He is currently covered by the PACT Act, which is legislation aimed at improving funding and healthcare access for veterans who were exposed to toxins during their service that was signed by President Joe Biden in August.

However, he, like thousands of others, are excluded from the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act, which only covers veterans present for atmospheric nuclear tests. RECA has had faster response times for claims than those submitted through the VA.

“We’re still fighting. We’re not gonna give up, and we’re just gonna keep going and keep fighting,” Brownell said. “The world needs to know. They need to know how dangerous the radiation is — how dangerous nuclear testing is.”

Plutonium’s Fatal Attraction

In February 2022, on the first day of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Russian forces took over the Chornobyl Zone of Alienation, an exclusion zone surrounding the plant created in the weeks after the Chornobyl accident. A month later, the Russian Army occupied the Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant in southern Ukraine, and since then, the plant has been repeatedly under fire. At the start of the invasion, the world seemingly received an education in nuclear power. News reporting illuminated that containment vessels protecting nuclear reactors had been stress-tested for tornadoes, tsunamis, and planes landing on them, but not for something so banal and human as a conventional war.

The public also came to understand that nuclear reactor complexes require a steady supply of electricity to keep running and to prevent overheating, and also that nuclear power plants hold years of highly-radioactive spent nuclear fuel—chock full of plutonium, among other harmful isotopes—which are not protected by containment buildings.

e-flux Architecture, Kate Brown, Half-Life, December 2022

Think of the earth. At its core is fire, an inferno around which biological life emerged. With fire in our planetary loins, no wonder humans have trouble staying away from it; that they delight in reproducing it in fiction, movies, fireworks, war games, and in technologies.

Perhaps that is why, decades after radioactive toxins saturated the Earth’s surface and at a time when threatened reactors in war-torn Ukraine are at risk of blowing again, many people are still enchanted by nuclear reactors. They are burning cores, sources of other-worldly heat and energy. If you can harness plutonium, the element at the heart of the nuclear inferno, then you can magnify human power to a super-hero level. In tandem, plutonium has the power to re-map territories, produce new borders—not just between people, but between humans and the environment. By extension, plutonium spatializes power.

In 1940, Glenn Seaborg first synthesized plutonium in a cyclotron in Berkeley, California. With these initial micrograms, plutonium became the first human-produced element on the periodic table. Plutonium has a half-life of 24,000 years, which means that Seaborg’s plutonium will linger on earth for over 240,000 years. Like all good offspring, plutonium promises to outlast humans on Earth.

Plutonium is also beautiful, sensual, and kaleidoscopic. It is a heavy metal that self-heats, warming a person’s hands like a small animal. In metallic form, plutonium is yellow or olive green. Shine a UV light on it, and it glows red. When it comes in contact with other radioactive isotopes plutonium sends out a dazzling blue light, a light show designed and powered by what appears to be an inert, inanimate metal. But it is not.

In 1943, the DuPont Corporation built a massive factory for the Manhattan Project to produce the world’s first industrial supplies of plutonium in the eastern reaches of Washington State. As engineers drew up plans for nuclear reactors and radio-chemical processing plants necessary for production, Dupont officials learned something alarming: “the most extreme health hazard is the product itself.”1 “It is now estimated,” DuPont executive Roger Williams wrote to the US Army Corps of Engineers overseeing the project, “that five micrograms (0.000005 grams) of the product [plutonium] entering the body through the mouth or nose will constitute a lethal dose.” A Manhattan Project medical officer wrote on the margins of this sentence: “Wrong!” With the first birthing pains of plutonium, a debate was born over the lethality and consequent liabilities inherent in nuclear industries.

Plutonium is a monumental invention, akin to harnessing fire. Upscaling the Pu chemical extraction process meant separating plutonium from about a hundred thousand curies of fission fragment radiation every single day. This was an incredibly dangerous undertaking. Plant operators worked with robotic arms and protective gear behind massive concrete walls and thick lead-glass windows in ship-sized “canyons.” They worked toward a final product that had extraordinary properties. Seaborg described element 94:

Plutonium is so unusual as to approach the unbelievable. Under some conditions it can be nearly as hard and brittle as glass; under others, as soft and plastic as lead. It will burn and crumble quickly to powder when heated in air, or slowly disintegrate when kept at room temperature. It undergoes no less than five phase transitions between room temperature and its melting point… It is unique among all of the chemical elements. And it is fiendishly toxic, even in small amounts.

Plutonium made not only a novel weapon of war, but its special existence inspired people to use it to create new technologies, and it gave birth to an elaborate security apparatus to safeguard the “super-poisonous” product, and later, new border zones to protect regions spoiled by the spillage of plutonium and other radioactive byproducts after accidents. As workers over subsequent decades produced more and more plutonium, the new mineral transformed landscapes, science, energy production, and human society around the world. Plutonium militarized, segregated, and compartmentalized large parts of the Earth, leaving a profound shadow that reaches into the twenty-first century.

Plutonium Landscapes

At the Hanford Plutonium Plant in Richland, Washington, DuPont engineers initially dedicated minimal resources to the management of growing volumes of radioactive waste. They had chosen a sparsely populated site and removed several towns and a settlement of the Wanapum nation from the newly designated “federal reservation” in case of accidents and the leakage of radioactive waste. They often repeated the platitude: “diffusion is the solution.” With a good bit of distance and privacy won with an elaborate security apparatus, DuPont and Army Corps engineers set up waste facilities for non-radioactive debris according to existing, standard practices. They drilled holes, called “reverse wells,” for dumping liquid radioactive waste. They bulldozed trenches and ponds, pouring in radioactive liquid and debris. Cooling ponds attached to reactors held hot, radioactive water for short periods before flushing it into the Columbia River. Smokestacks above processing plants issued radioactive particles in gaseous form. High-level waste—terrifically radioactive—went into large, single-walled steel coffins buried underground. Engineers designed these chambers for temporary, ten-year storage with the knowledge that the waste would corrode even thick steel walls.

DuPont leaders were nervous about these waste management procedures. The corporation had experience polluting rivers and landscapes with chemical toxins near their factories, and insisted that the Army Corp pay for environmental assays to learn what happened to the dumped radioactive waste. At Hanford in the 1940s, Dupont set up a soil study, a meteorological station, and a fish lab to monitor the health of valuable salmon migrations in the Columbia River. The studies showed that while it took large hits of external gamma rays to kill fish, much smaller ingested doses weakened and killed fish and other experimental animals. Weather studies showed that radioactive gases either traveled considerable distances in strong winds or hovered for long periods over the Columbia Basin when caught in an inversion. Researchers found, in short, that radioactive waste did not spread in a diffuse pattern, but collected in random hot spots of radioactivity. Soil scientists discovered that plants drank up radioactive isotopes readily from the soil and that aquifers became contaminated with radioactive liquids. Ichthyologists learned that fish concentrated radioactivity in their bodies at levels at least sixty times greater than the water in which they swam. Generally, researchers found that radioactive isotopes attached to living organisms readily made their way up the food chain.

Despite this troubling news, even after September 1946 when General Electric took over the running of the plant, no major changes were made to waste management methods for thirty years. In the course of forty-four years, Hanford rolled out the plutonium content for 60,000 nuclear weapons.4 The environmental footprint of that military production, however, is immeasurable. Indeed, it is intrinsically shape-shifting.

Rushing to develop their own bomb and encouraged by the example of the United States, Soviet leaders followed American practices in the years following World War II. Soviet generals commanded Mayak, a site in the southern Russian Urals that became known as “Post Box 40.” Engineers at Mayak dumped radioactive waste into the atmosphere, ground, and local water sources. High-level waste was contained temporarily in underground tanks similar to those built at Hanford. Unlike the high-volume, rocky Columbia River, the nearby Techa River flowed slowly, flooding frequently and bogging down in swamps and marshes. After just two years of operation of the Mayak Plutonium Plant, its director deemed the Techa River “exceedingly polluted.”5 By 1949, when the first Soviet nuclear bomb was tested, the plant’s underground containers for high-level waste were overflowing. Rather than shutting down production while new containers were built, plant directors decided to dump the high-level waste in the turgid Techa River.6 Each day, four thousand three hundred curies of waste? flowed down the river. From 1949 to 1951, when dumping ended, plant effluent comprised a full twenty percent of the river. A total of 3.2 million curies of waste clouded the river along which 124,000 people lived.7 Radioactivity became a new contour that outlined human activity and new communities of people who shared in dangerous exposures.

Rushing to develop their own bomb and encouraged by the example of the United States, Soviet leaders followed American practices in the years following World War II. Soviet generals commanded Mayak, a site in the southern Russian Urals that became known as “Post Box 40.” Engineers at Mayak dumped radioactive waste into the atmosphere, ground, and local water sources. High-level waste was contained temporarily in underground tanks similar to those built at Hanford. Unlike the high-volume, rocky Columbia River, the nearby Techa River flowed slowly, flooding frequently and bogging down in swamps and marshes. After just two years of operation of the Mayak Plutonium Plant, its director deemed the Techa River “exceedingly polluted.”5 By 1949, when the first Soviet nuclear bomb was tested, the plant’s underground containers for high-level waste were overflowing. Rather than shutting down production while new containers were built, plant directors decided to dump the high-level waste in the turgid Techa River.6 Each day, four thousand three hundred curies of waste? flowed down the river. From 1949 to 1951, when dumping ended, plant effluent comprised a full twenty percent of the river. A total of 3.2 million curies of waste clouded the river along which 124,000 people lived.7 Radioactivity became a new contour that outlined human activity and new communities of people who shared in dangerous exposures.

Villagers used the river for drinking, bathing, cooking, and watering crops and livestock. Soviet medical personnel investigated the riverside settlements in 1951 and found most every object and body contaminated with Mayak waste. Blood samples showed internal doses of uranium fission products, including cesium-137, ruthenium-106, strontium-90, and iodine-131. Villagers complained of pains in joints and bones, digestive tract illnesses, strange allergies, weight loss, heart murmurs, and increased hypertension.8 Further tests showed that blood counts were low and immune systems weak. Soviet army soldiers carried out an incomplete evacuation of riverside villages over the next ten years. Twenty-eight thousand people, however, remained in the largest village, Muslumovo. They became subjects of a large, four-generation medical study. In subsequent years, prison laborers created a network of canals and dams to corral radioactive waste streams into Lake Karachai, now capped with crumbling cement and considered the most radioactive body of water on earth.

Radioactive waste redraws the spatial relationships between humans and environment on the ground and by air. On September 29, 1957, an underground waste storage tank exploded at the Mayak plutonium plant in the southern Urals. The explosion sent a column of radioactive dust and gas rocketing skyward a half mile. Twenty million curies of radioactive fallout spread over a territory four miles wide and thirty miles long. An estimated 7,500 to 25,000 soldiers, students, and workers cleaned up radioactive waste ejected from the tank. Witnesses described hospital beds fully occupied and the death of young recruits, but the fate of 92% of the accident clean-up crew is unknown. Following the radioactive trace, soldiers evacuated seven of the eighty-seven contaminated villages downwind from the explosion. Residents of the villages that remained were told not to eat their agricultural products or drink well water, an impossible request as there were few alternatives. In 1960, soldiers resettled twenty-three more villages. In 1958, the depopulated trace became a research station for radio-ecology.

Plutopia

In the postwar era, the social consequences of the production and dispersal of large volumes of invisible, insensible radioactive toxins were profound, manifesting in sophisticated spatial planning and infrastructure that appropriated and exploited existing inequities. Plant managers in the US and USSR created special residential communities—“nuclear villages” in the US and “closed cities” in the USSR—to both manage and control the movement of workers and radioactive isotopes. In exchange for the risks, workers in plutonium plants were paid well and lived like their professional class bosses. As part of the bargain, they signed security oaths and agreed to surveillance of their personal and medical lives. They remained silent about accidents, spills, and intentional daily dumping of radioactive waste into the environment. Free health care and a show of monitoring employees and the nuclear towns led workers to believe they were safe.

To protect full-time employees, much of the dirty work of dealing with radioactive waste and accidents fell to temporary, precarious labor in the form of prisoners, soldiers, and migrant workers, often of ethnic minorities (Muslims in the USSR, Latinos and Blacks in the USA). Segregating space by race to disaggregate “safe” places—or what I call plutopias—and sacrifice zones became a larger pattern in Soviet and American Cold War landscapes.

Soviet and American plutonium communities surfed on a wave of federal subsidies in company towns in isolated regions where there were no other industries and few alternative sources of employment for plant workers. Leaders found it politically difficult to shut off the good life they had created for their plutopias. In Richland, Washington, when the supply of plutonium had been satiated, city leaders campaigned to keep their plants going nonetheless, resulting in an overwhelming excess.11 By the 1980s, the US had produced fifty percent more plutonium than that which was deployed in nuclear warheads.

American officials explored other uses for plutonium. In 1953, President Dwight Eisenhower announced a new international program, Atoms for Peace. At the time, this was largely a propaganda slogan to counter Soviet officials who frequently pointed out that the US was the only nation to use nuclear weapons to kill.

In the next decade, engineers and physicists devised new, non-military uses for plutonium and its radioactive by-products. Turbines attached to reactors began to produce plutonium for (very expensive) generation of electricity. Scientific experiments tested plutonium in cancer research, as a power source for pacemakers, and even for instruments for espionage.12 It seemed there was no end to the uses of plutonium and its radioactive by-products. In the 1950s and 1960s, American radioactive isotopes were shipped abroad under the Atoms for Peace logo in great quantities, dispersing and propagating nuclear technologies across the globe. This trade was both open and clandestine.13 In the name of “peace,” US not only gave other nations the possibility to build nuclear weapons, but also to expose civilian populations as well.

One of the most critical technologies that US agencies exported were “civilian” nuclear power plants. Advocates for nuclear power have long carefully drawn boundaries between nuclear weapons and nuclear power generation. But the existence of nuclear power reactors opened the door for the production of plutonium at the core of nuclear missiles and nuclear accidents. In the late 1960s, both the US and USSR created so-called “dual-purpose reactors” that erased the already-questionable boundaries between peaceful and martial nuclear technologies. These reactors were designed to produce either electricity to power a grid or plutonium for the core of a nuclear missile.

American engineers created the N-reactor at the Hanford Nuclear Reservation in Richland, Washington, while Soviet engineers designed the RBMK-1000 reactor, a standardized model that was built over a dozen times in the USSR. In contrast to the US, Soviet leaders were worried that the RBMK-1000’s plutonium-generating capabilities could be abused if their technology was shipped abroad.

………………………………………………………… Geopolitics could not reconcile the way that nuclear contaminants did not respect borders. For most officials in the USSR and abroad, the solution was silence and suppression. To admit in the 1990s to the ongoing public health disaster in Ukraine and Belarus would mean acknowledging the damage done to populations around the globe exposed to Cold War nuclear experimentation, weapons production, nuclear testing, and future nuclear accidents. But underestimating and obscuring the effects of Chornobyl has left humans unprepared for the next disaster.

In the years after 1986, commentators repeated that a tragedy like Chornobyl could never occur in a developed, industrial country. This claim was dispelled, however, in 2011, when a tsunami crashed into the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant. Japanese business and political leaders responded in ways eerily similar to Soviet leaders twenty-five years earlier. They grossly understated the magnitude of the disaster (a meltdown of three reactors), sent in firefighters unprotected from the high fields of radioactivity, raised the acceptable level of radiation exposure for the public twenty-fold, and dismissed a recorded increase in pediatric thyroid cancers.

In February 2022, on the first day of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Russian forces took over the Chornobyl Zone of Alienation, an exclusion zone surrounding the plant created in the weeks after the Chornobyl accident. A month later, the Russian Army occupied the Zaporizhzhia Nuclear Power Plant in southern Ukraine, and since then, the plant has been repeatedly under fire.

At the start of the invasion, the world seemingly received an education in nuclear power. News reporting illuminated that containment vessels protecting nuclear reactors had been stress-tested for tornadoes, tsunamis, and planes landing on them, but not for something so banal and human as a conventional war. The public also came to understand that nuclear reactor complexes require a steady supply of electricity to keep running and to prevent overheating, and also that nuclear power plants hold years of highly-radioactive spent nuclear fuel—chock full of plutonium, among other harmful isotopes—which are not protected by containment buildings.

The ongoing war in Ukraine has shown how vulnerable electric power grids are in times of war and, one can presume, in scenarios of extreme weather, triggered by climate change. The grounded sites of nuclear events, whether on the high plains of Eastern Washington, the birch-pine forests of the Russian Urals, the swampy stretches of Northern Ukraine, or in coastal Japan, have a global reach. The impact of the invention of plutonium, a new element on the periodic chart, reshaped landscapes, reconfigured spatial and security regimes, and remade what we understand to be human bodies, which have all incorporated radioactive isotopes. Watching the crisis in Ukraine unfold in real-time, a global audience has learned that humanity’s attraction to fire continues to be a fatal one.

Notes………………. https://www.e-flux.com/architecture/half-life/507133/plutonium-s-fatal-attraction/

Large Multinational Study Shows Link Between CT Radiation Exposure and Brain Cancer in Children and Young Adults

https://www.diagnosticimaging.com/view/clinical-histories-in-radiology-could-they-get-worse-

December 9, 2022, Jeff Hall

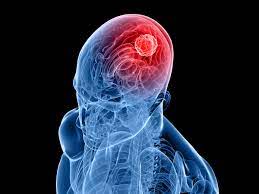

In a new study based on five- to six-year follow-up data from over 650,000 children and young adults who had at least one computed tomography (CT) exam prior to the age of 22, researchers found a “strong dose-response relationship” between increased CT radiation exposure and brain cancer.

Increased cumulative exposure to radiation from computed tomography (CT) exams led to elevated risks for developing gliomas and other forms of brain cancer in children and young adults, according to the findings of a large multinational study of data from over 650,000 patients.

In the study, recently published in the Lancet Oncology, researchers reviewed pooled data from nine European countries and a total of 658,752 patients. All study participants had at least one CT exam prior to the age of 22 with no prior cancer or benign brain tumor, according to the study. Examining follow-up data at a median of 5.6 years, the study authors noted 165 brain cancers (including 121 gliomas). They also found that the overall mean cumulative brain radiation dose, lagged by five years, was 47.4 mGy for the study cohort in comparison to a mean cumulative brain radiation dose of 76.0 mGy for those with brain cancer.

“First results of (the study) after a median follow-up of 5.6 years show a strong dose-response relationship between the brain radiation dose and the relative risk of all brain cancers combined and glioma separately; a finding that remains consistent for doses substantially lower than 100 mGy,” wrote lead study author Michael Hauptmann, Ph.D., a professor of Biometry and Registry Research at the Brandenburg Medical School Theodor-Fontane in Neuruppin, Germany, and colleagues.

For head and neck CT exams, the researchers noted a “significant positive association” between the cumulative number of these procedures and elevated brain cancer risk. Employing linear dose-response modelling, the researchers found a 1.27 excess relative risk (ERR) per 100 mGy of brain radiation dosing for all brain cancers, a 1.1 ERR for gliomas and a 2.13 ERR for brain cancers excluding gliomas, according to the study.

Hauptmann and colleagues acknowledged that the risk estimates in the study translate to one out of 10,000 children experiencing a radiation-induced brain cancer five to 15 years after a head CT exam. However, the researchers also emphasized appropriate caution, pointing out annual estimates of pediatric head CT exams surpassing one million in the European Union and five million in the United States.

“These figures emphasize the need to adhere to the basic radiological protection principles in medicine, namely justification (procedures are appropriate and comply with guidelines) and optimization (doses are as low as reasonably achievable),” added Hauptmann and colleagues.

Study limitations included the potential for confounding indications with the study authors noting the inclusion of studies with some patients having congenital syndromes that may be predisposing factors for brain tumor development. However, Hauptmann and colleagues noted that exclusion of those patients and adjustments for those conditions saw no significant effect on the assessment of ERR.

The study authors also noted a lack of information on other imaging, such as nuclear medicine studies and X-rays, that may have been performed in the study population. However, they suggested the contribution of radiation dosing from these exams “is probably minor” in comparison to higher frequencies and dosing seen with pediatric head CT exams.

Missouri Community and Its Children Grappling With Exposure to Nuclear Waste

In the 2022 report, BCDC took 32 soil, dust, and plant samples throughout the school buildings and campus. Using x-ray to analyze the samples BCDC found more than 22 times more lead-210 than the estimated exposure levels for the average US elementary school in the Jana Elementary playground alone. There were also more than 12 times the lead-210 expected exposure in the topsoil of the basketball courts alone.

Radioactive isotopes of polonium-210, radium-266, thorium-230, and other toxicants were also found in the library, kitchen, ventilation system, classroom surfaces, surface soil and even soil as far as six feet below the surface.

https://blog.ucsusa.org/chanese-forte/missouri-community-and-its-children-grappling-with-exposure-to-nuclear-waste/ Chanese Forte, December 8, 2022

The families, students, and school officials in Florissant, Missouri have been living a modern nightmare for the past several weeks, learning that Jana Elementary school and the surrounding region has high levels of radiation, a problem caused decades ago by the production of nuclear weapons

Radiation exposure can damage the DNA in cells leading to a host of health problems including cancer and auto-immune disorders. What’s more troubling is that the Centers for Disease Control reports that children and young adults, especially girls and women, are more sensitive to the effects of radiation.

Jana Elementary school has 400 students and a predominantly (82.9%) Black student body. Unfortunately, the United States has a long history of environmental racism which results in harming Black, Indigenous and Brown communities much more in the process of creating and maintaining nuclear weapons.

When science cannot agree, the community suffers

The suburban school north of St. Louis, Missouri, was thought to be safe for students based on research completed in 2000 by the Army Corps of Engineers (USACE).

Specifically, USACE has been in the Coldwater Creek region for the last 20 years attempting to remediate radioactive waste associated with the creek (which does not include Jana Elementary).

Toward the start of the 2022 semester, as part of an ongoing lawsuit in the region the Boston Chemical Data Corp (BCDC), an environmental consulting group, reported the elementary school as having radioactive waste levels far above the estimated national levels.

These radioactive waste exposures—like lead-210—are associated with decreased cognition, brain defects, thyroid disease, and cancer, and can accumulate in the body over time.

Following the BCDC report, all Jana Elementary students were sent home for the rest of the semester in hopes their homes were less toxic.

By the Thanksgiving holiday break, the USACE returned to test inside and on the playground of the school and found no radiation on the campus, news which many community members and organizers unsurprisingly expressed as suspicious.

The School Board then hired SCI Engineering, a private engineering firm, to sample Jana Elementary who came to a similar conclusion as USACE.

Now returning to classes from Thanksgiving break, many wary students joined classes at new schools in the area per the school board’s decision related to BCDC’s radiation exposure assessment. Many parents also expressed to National Public Radio they felt left out of discussions for decisions being made.

How did radioactive waste end up in Florissant, MO?

The region near Jana Elementary was first contaminated by the US Department of Energy’s decision to make St. Louis one of the processing sites for uranium during the Manhattan Engineering District project. These nuclear weapons were built through World War II and originally stored at the St. Louis Lambert International Airport.

Unfortunately, the waste was later illegally dumped in 1973 at the West Lake Landfill in Bridgeton, MO, which lies about 10 miles Southwest of Jana Elementary. The West Lake Landfill is located near the Mallinckrodt Chemical Works Company which regularly floods, causing these harmful chemicals to be carried away by nearby water ways like Coldwater Creek.

Coldwater Creek runs for 19 miles throughout the area and flows directly into the Missouri River. Jana Elementary, just North of St. Louis, is bordered by the creek on two sides but has to date not been included in any clean-up efforts by the US Army Corps of Engineers (USACE).

US Army Corps of Engineers initially didn’t sample inside or outside of Jana Elementary

Prior to the Boston Chem Data Corp 2022 report, the USACE did not take any samples within 300 feet of the school building in their 2017 assessment. According to BCDC’s report, this doesn’t follow US Agency for Toxic Substances Disease Registry (ATSDR) standards for radioactive sampling.

In fact, it ignores the conclusion ATSDR made that most exposures in the region will be indoors and just outdoors of buildings.

Indoor samples from creek-facing homes in the same neighborhood as Jana Elementary had similar radioactive waste both indoors and outdoors. ATSDR also noted in a 2019 report that radioactive wastes are routinely moved from Coldwater Creek into homes due to flooding. The region floods frequently which is only increasing due to climate change in the region.

New radioactive sampling methods used to understand student exposure

In the 2022 report, BCDC took 32 soil, dust, and plant samples throughout the school buildings and campus. Using x-ray to analyze the samples BCDC found more than 22 times more lead-210 than the estimated exposure levels for the average US elementary school in the Jana Elementary playground alone. There were also more than 12 times the lead-210 expected exposure in the topsoil of the basketball courts alone.

Radioactive isotopes of polonium-210, radium-266, thorium-230, and other toxicants were also found in the library, kitchen, ventilation system, classroom surfaces, surface soil and even soil as far as six feet below the surface.

Marco Kaltofen, an environmental engineer who is leading the BCDC team, collected roughly 1,000 samples from across the region as a part of law suit efforts. There are several businesses and homes also indicated as exposed in the lawsuit as well.

Overall, Kaltofen suggests that BCDC’s unprecedented x-ray method better picks up the microscopic radioactive materials. However, he also asserts both studies are essentially saying the same thing, which is of course confusing for many community members.

Community organizers fight for testing and clean-up

Just Moms STL activist Dawn Chapman has worked tirelessly since 2014 to get the federal government to test for radioactive material in more regions where the creek floods.

The co-founder of Just Moms STL, Karen Nickel, also attended Jana Elementary School and has reported currently living with several autoimmune disorders. She uses her experience and love of the area to battle these exposure injustices.

In a 2017 Nation Public Radio report, Ms. Chapman says,

“They [The US Government] fought us for years. Finally, they [tested] parks that had flooded, and found [radioactive waste]. They started testing some backyards and found it. We pushed for Jana Elementary, because it is the closest school to the creek.” Just Moms STL activist, Dawn Chapman

We reached out to Just Moms STL to understand what the next steps are. Just Moms STL Recommends:

- The sites in St. Louis should be expeditiously cleaned up.

Unfortunately, Jana Elementary School is not the only place to be concerned about near St. Louis.- Since remediation of nuclear weapons waste in the area has already taken decades, many of these students will likely age out of Jana Elementary School before there is full remediation of radioactive waste in the St. Louis area.

While there is guidance on defining “safe” or acceptable radioactive exposure levels as it relates to human health, scientists also calculate “expected” levels from the Earth naturally (like radon in sediment).

Unacceptable levels are frequently defined as radiation exposure above natural levels by communities.

- However, legally the Army Corps is allowed to leave some radioactive residue above naturally occurring levels, and Just Moms STL would like this to no longer be the case.

- Residents near nuclear weapon processing sites like the St. Louis area should be included in federal radiation compensation programs, such as the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act (RECA). UCS also suggests consideration of St. Louis in the Energy Employees Occupational Illness Program Act (EEOICPA), and other forms of compensation as well.

Expanding radiation compensation programs is complicated because the list of communities that want to be included who currently qualify is long. Moreover, Just Moms STL says the RECA program needs to be expanded to include processing sites like St. Louis, which has previously only applied to nuclear testing exposure sites and uranium workers, or EEOICPA, which has only covered nuclear site workers, but not surrounding communities.

There are currently two bills being proposed to the House and Senate to extend and strengthen RECA. Just Moms STL is working to get Missouri elected officials to help sponsor and carry RECA as well. And your representatives may also be interested in supporting adjustments to RECA or the EEOICPA.

What are the risks and treatment if nuclear power plant radioactivity is released?

Russia’s war renews nuclear disaster fears. What to know about the dangers of radiation., Trevor Hughes, USA TODAY 8 Dec 22

“…………………………………………………. A leak from Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant is among the highest risk, experts told USA TODAY, because Russia has deliberately targeted the area. Zaporizhzhia is Europe’s largest nuclear power station and has been under Russian control since shortly after the invasion.

The U.N. International Atomic Energy Agency is trying to establish a safety zone around the plant because while nuclear power plants are built to withstand many natural disasters, few are designed to survive direct military attacks, said Edwin Lyman, a nuclear expert with the Union of Concerned Scientists. An attack on the plant could potentially release intense radiation in a small area and weaker radioactive particles over a wider area.

“The fact that Russia would want to seize that plant, it’s not surprising,” said Lyman. “I think it’s sort of inevitable. And it’s something the industry never wanted to think about.”

The Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant, which is also in Ukraine, is not considered a serious potential source of radiation leakage, in part because its 1986 meltdown led to its shutdown and removal of its nuclear fuel system. However, the Health Physics Society says there could be small, localized releases of radioactive material if the area is disturbed.

Chernobyl disaster:A look at the what happened, 30 years later

What happened following the Chernobyl meltdown could be the same as for Zaporizhzhia: A relatively small number of plant operators exposed to intense radiation, and then broader contamination carried in the wind and water absorbed into the land and animals. Nuclear power plants are designed to avoid the kind of explosion created by a nuclear bomb.

According to the CDC, exposure to Acute Radiation Syndrome only happens to people exposed to intense radiation, generally in a very short period of time. That could be someone working in a nuclear power plant during a meltdown, or someone near the site of nuclear weapon’s detonation.

For these people, specialized treatments to protect their bone marrow and stomach lining — vomiting and nausea are common signs of ARS — are available but not widely distributed, according to the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission.

For the public, authorities often have stockpiles of potassium iodide pills, especially in areas close to nuclear power plants. The iodide pills help prevent the thyroid gland from absorbing radiation, which could lead to tumors, but do not treat other kinds of radiation exposure, according to the CDC.

Authorities typically maintain stockpiles of the pills but don’t give them out unless there’s a confirmed release, and even then, they are typically given to people 40 and younger because they are most at risk for developing thyroid problems later in life.

For people who are near a reactor accident but not immediately harmed, the CDC recommends they get or stay inside to avoid any potentially radioactive dust or smoke, remove and bag up any potentially contaminated clothing, and then shower to remove any particles on exposed skin and hair.

A nuclear risk ‘nightmare’? After seizing Chernobyl, Russian troops exposed themselves to radiation

What are the risks and treatment for a dirty bomb?

Federal officials say a “dirty bomb” would typically be created by taking conventional explosives and adding in radioactive materials that would be dispersed by the explosion. It wouldn’t cause as big of an explosion as a nuclear weapon — nor release the same kind of intense radioactivity — but would potentially disperse radioactive particles over a large area, potentially causing panic and evacuations.

Protection for exposure to a dirty bomb is similar to that of a reactor incident: Get or stay inside, get rid of potentially contaminated clothing, and then shower.

Potassium iodide pills would likely not be recommended for that kind of radiation exposure, the CDC says, but a treatment based on a drug called Prussian blue could be used.

Radiogardase, the brand name, was approved by the FDA in 2003 to help treat cesium or thallium exposure. Those radioactive substances are often used in medical treatments for cancer, but federal officials say they could also be used in a dirty bomb because they are more widely available. The federal government maintains a stockpile of Prussian blue and other drugs to treat radioactivity exposure.

What are the risks and treatment for a nuclear weapon?

A nuclear explosion is the worst combination of all: an intense blast of radioactivity followed by the fallout of radioactive particles that would contaminate the air, water and ground, along with animals and other food sources.

The same advice follows for people near an explosion but not harmed: get inside, get rid of contaminated clothing, and shower. The U.S. government stockpiles would also come into play.

Lyman, the nuclear expert, said the key question is whether those treatments can be effectively distributed following a nuclear attack on the United States.

“If you had a large nuclear weapon detonated, and you had hundreds of thousands of people affected, you’d need to treat them in a day,” he said. “Having the drugs is one thing. Having a plan to actually use them is another. I wouldn’t count on those interventions. Prevention is where you have to put most of your effort.” https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/health/2022/12/08/nuclear-disaster-russian-war-explained/8092631001/—

Protecting kids from electromagnetic radiation in school and at home

EWG Nov 22

EWG’s big picture recommendations for wireless devices

- Default to airplane mode.

- Increase distance from devices.

- Turn off when not in use.

- Used wired devices if possible.

Children are almost constantly exposed to wireless [electromagnetic] radiation, starting as early as the first weeks of life. As they get older, that exposure grows every day, thanks to the widespread use of smartphones, laptops and other wireless devices in the classroom and at home.

Wireless devices radiate radiofrequency electromagnetic fields. Research has raised concerns about the health risks of exposure to this radiation, including harm to the nervous and reproductive systems, and higher risk of cancer. Cell phone radiation was classified a “possible carcinogen” in 2011 by the International Agency for Research on Cancer, part of the World Health Organization. The agency said human epidemiological studies showed a link between higher risk of a type of malignant brain cancer and cell phone use.

At home

Parents and caregivers can exert more control over their kids’ wireless radiation exposure at home than at school, and have more latitude to try new ways of using devices.

Getting started

To begin, inventory your home’s electronic devices. ………………………………………….

At night

- Strongly encourage your child not to sleep near their wireless gadgets. If this isn’t possible – and let’s face it, with teenagers, you may not succeed at wresting the phone or tablet away – try to convince them to place it away from their head instead of under a pillow.

- Even better, keep electronics out of bedrooms as much as possible, or at least away from beds. This includes TV screens and audio speakers.

- Use an old-fashioned electric or battery alarm clock that doesn’t connect to Wi-Fi. And get one for your children if they claim to need their cell phone so they can get up in the morning.

- Move beds away from utility meters or large appliances, which also emit radiation, even if they’re on the other side of a wall.

……………………. Studying, playing and communicating

- Experts recommend starting a child’s cell phone use as late as practical, considering the family and educational context and needs of each child. The younger kids are, the more vulnerable their bodies are to potentially harmful effects of wireless radiation exposure.

At school……………………………….

For more information

To find additional resources, advocacy guidance, tip sheets and other useful suggestions, consult the websites of one of these organizations:

- The Environmental Health Trust’s “Wi-Fi in Schools Toolkit” offers a wealth of resources, including fact sheets and tip sheets, background on the science of EMF exposure, and guidance for parents, teachers and schools. It also has more than a dozen downloadable and printable posters on exposure and sleep, children’s development, and the effects of EMF exposure on breast cancer risk and male reproductive health.

- An Environmental Health in Nursing textbook downloadable chapter on EMF, courtesy of the Alliance of Nurses for Healthy Environments, contains useful information, like a detailed explanation of the health impacts of EMF exposure, advocate organizations’ tip sheets, and other valuable resources.

- The American Academy of Pediatrics issued recommendations about EMF exposure.

- The Massachusetts Breast Cancer Coalition offers a downloadable backgrounder for students and educators on “Cell Phones, Wireless and Your Health,” which includes suggested activities to use in the classroom and as homework. It includes a list of additional websites you may choose to consult. https://www.ewg.org/news-insights/news/2022/11/protecting-kids-wireless-radiation-school-and-home

Closed Dounreay nuclear site records its highest number of radioactive particles in nearly two decades

. Fifteen radioactive particles have been discovered at a

nuclear site in Scotland that is currently being decommissioned, marking

the highest reported number in nearly two decades.

The particles contained niobium 94, which has a half life of 20,300 years, Americium-241, which has

a half life of 432.2 years, caesium 137, which has a half life of 30 years,

and cobalt 60, which has a half life of around 5.3 years. Eleven of the

finds were categorised as “significant”, which is the highest hazard

level used.

ENDS 9th Nov 2022

‘Clear case for inquiry into treatment of men in Britain’s nuclear test programme’

Mirror 10th Nov 2022, https://www.mirror.co.uk/news/politics/clear-case-inquiry-treatment-men-28463111

These brave men were exposed to levels of radiation subsequently linked to higher-than-average rates of cancer and birth defects

There is now a clear case for a public inquiry into the scandalous treatment of the men who took part Britain’s Cold War nuclear test programme.

Throughout our long campaign to win them justice, the Ministry of Defence has sought to confuse the issue and obstruct any inquiries.

These brave men were exposed to levels of radiation subsequently linked to higher-than-average rates of cancer and birth defects.

They have received no recognition, no medals and no compensation.

The MoD allegedly knew full well the dangers and sought to cover them up.

Nuclear test vet heroes denied truth as government ‘committed crimes against own servicemen’

Some documents which would reveal the truth have been withdrawn from the public record. Medical records have reportedly been falsified, withheld or destroyed.

An inquiry must examine not just the test programme but also the culture of secrecy which has added to families’ distress.

The poppy to be worn by Rishi Sunak at the Cenotaph this weekend is meant to be tribute to those who served the nation. If he really wants to support military personnel past and present he will act now

Councillor wants to know why there has been an increase in radioactive particles found on Dounreay foreshore.

A Caithness councillor wants to know

why there has been an increase in the number of radioactive particles found

on the foreshore at Dounreay this year. Struan Mackie, a Thurso and

Northwest Caithness Highland councillor and chairman of the Dounreay

Stakeholder Group (DSG), made the call after 15 irradiated particles were

discovered on the foreshore area between February and March. It is

understood to be the highest number since 17 were found in 1996.

Mr Mackie

said: “We wish to ascertain why there has been an increase in particle

detections and whether this was preventable. “Regular public updates are

provided to the Dounreay Stakeholder Group through our Site Restoration

sub-group, and it is of the utmost importance that these matters are dealt

with in a robust but transparent manner.”

Dounreay confirmed there has been

an increase in the number of particles found on the foreshore. A

spokeswoman said: “We closely monitor the environment around the site and

have seen an increase in particles found on the Dounreay foreshore this

year. “The foreshore is not used by the general public. We are looking at

wind and wave data to see if we can pinpoint a trend, and will report our

findings when they are complete. Safety is our number one priority and we

continue to monitor the foreshore on a regular basis.

John O’Groat Journal 4th Nov 2022

Studies on nuclear radiation’s impact on people necessary: BRIN

https://en.antaranews.com/news/258613/studies-on-nuclear-radiations-impact-on-people-necessary-brin 4 Nov 22, Jakarta (ANTARA) – Environmental and health studies on the impact of radiation exposure on people living in areas of high natural radiation, such as Mamuju, West Sulawesi, are necessary, the National Research and Innovation Agency (BRIN) has said.

A researcher from BRIN’s Research Center for Metrology Safety Technology and Nuclear Quality, Eka Djatnika Nugraha, said that in some places in Indonesia, such as Mamuju, people have been exposed to natural radiation that is several times higher than the global average at around 2.4 millisieverts per year.

“This situation may pose a health risk to the public due to chronic external and internal exposure,” Nugraha said in a statement received on Friday.

Mamuju is an area of high natural background radiation due to the high concentration of uranium and thorium in the rocks and soil, he observed.

Thus, studies on the health of people living in such areas could serve as a potential source of information about the effects of chronic low-dose exposure, he added.

In order to obtain scientific evidence on the effects of chronic low-dose radiation exposure on health, it is necessary to conduct a comprehensive environmental assessment of the exposure situation in areas of high natural radiation, he elaborated.

Meanwhile, head of BRIN’s Nuclear Energy Research Organization, Rohadi Awaludin, said that it is important to know and understand the safety and protection measures against nuclear radiation technology, especially for everyone involved or in contact with it.

“Nuclear radiation technology, including ionization, has been used and applied to various aspects, including industry and health, food, and others. This technology is the answer to the problems we have, but there are also risks that (one) must be (aware of) from this technology,” he added.

Carbon-14: Another underestimated danger from nuclear power reactors

https://beyondnuclear.org/carbon-14-another-underestimated-danger-from-nuclear-power-reactors/ 1 Nov 22,

There are a number of radionuclides released from nuclear energy facilities. This paper highlights carbon-14 for a number of reasons:

- Carbon-14 is radioactive and is released into air as methane and carbon dioxide.

- Before 2010, carbon-14 releases from nuclear reactors were virtually ignored in the United States. Today only estimates are required and only under certain restrictive circumstances.

- There is no good accounting of releases to date, so its impact on our health, our children’s health, and that of our environment remains unknown, yet environmental measurement is possible, but can be challenging under certain conditions.

- Carbon-14 has a half-life of over 5700 years and the element carbon is a basic building block for life on earth. Therefore, “it constitutes a potential health hazard, whose additional production by anthropogenic sources of today will result in an increased radiation exposure to many future generations.”

- Like tritium, it can collect in the tissues of the fetus at twice the concentration of the tissues in the mother, pointing to its disproportionate impact on the most vulnerable human lifecycle: the developing child.

Dounreay nuclear plant radiation scare over high numbers of ‘harmful’ radioactive particles.

Highest number of nuclear particles found in 26

years and ‘they may pose risk’. A public health warning has been issued

after harmful radioactive particles were discovered to have leaked out in

the area surrounding Dounreay nuclear plant, in Caithness. Fragments of

irradiated nuclear fuel have been detected at the shoreline near the power

plant and nuclear testing facility, with experts from independent Dounreay

Particles Advisory Group saying they “pose a realistic potential to cause

harm to members of the public”.

The radioactive material is said to be the

at the highest levels almost three decades – with 73 per cent of the

particles found deemed “significant”, according to a report. A survey found

15 particles on the shoreline, the most since 1996 when 17 were found, The

Daily Mail reported.

It comes after research suggested the leaks occurred

sometime between 1958 and 1984. In response to ongoing concerns, Dounreay

Site Restoration Ltd, which is in charge of the plant’s clean-up, said it

was closely monitoring the situation.

It comes as Shaun Burnie of

Greenpeace Asia, a nuclear specialist who formerly worked at Dounreay, also

warns of the risk to public health. He said: “The scale of the radiological

hazard from the Dounreay particles is enormous, with hundreds of thousands

and more highly radioactive nuclear fuel particles on the sea bed.

Express 29th Oct 2022

‘The nuclear bomb was so bright I could see the bones in my fingers’: The atomic veterans fighting for justice

https://inews.co.uk/inews-lifestyle/nuclear-bomb-bright-bones-fingers-atomic-veterans-2-1930293 24 Oct 22, Veterans of British nuclear testing in the Cold War say they – and their children and grandchildren – are still living with the health effects. And 70 years on, they want to see recognition of their part in the missions

RAF veteran John Lax is about to describe what it’s like seeing a nuclear bomb being detonated. “Even if I tell you what it was like,” he tells i, “you probably can’t really imagine it unless you’ve witnessed it yourself.”

Now 81, Lax was a 20-year-old air wireless mechanic when he was sent to take part in Britain’s nuclear testing programme in the Pacific in 1962.

Like many servicemen, he didn’t know there would be bomb tests when he arrived on Christmas Island, then a British territory, now a republic named Kiribati.

“We were told to put on long trousers and a long-sleeved shirt,” he says, “and we had these dark goggles which meant you couldn’t see your hand in front of you. Then we had to go and sit on the football pitch with our backs to the detonation, because if we’d faced it, the fireball would have burned our eyes.

“When the bomb went off, it was so bright that I could see the spine and ribs of the guy sitting a metre in front of me, like an X-ray. I put my hands over my eyes and could see the bones in my fingers, and could see the blood pumping around my hands. It was 4am but the sky turned blue, like it was daytime. The blast was like the sound of a pistol, except 1,000 times louder. After the fireball, a couple of minutes later, you feel the blast and a strong gust of very hot wind – if you had no shirt on it feels like it would burn through your back – then once the fireball starts to dissipate you get the mushroom cloud.”

This month it is 70 years since Britain first began developing and testing nuclear weapons, becoming the world’s third nuclear power (after the United States and the Soviet Union).

Between 1952 and 1965, detonations were carried out in Australia and the Pacific, in a series of operations involving the participation of more than 20,000 British service personnel, as well as some Fijian and New Zealand soldiers. Inhabitants of the test areas were moved offshore or to protected areas.

Read more: ‘The nuclear bomb was so bright I could see the bones in my fingers’: The atomic veterans fighting for justiceLax, who bore witness to 24 nuclear detonations over 75 days, was at the time given a “film badge”, containing photographic material that was intended to measure the levels of radiation the young men had been exposed to.

“They weren’t much good,” he says, “nobody kept a record of who had which badge, and you’d just put it in a box with all the other badges. These badges are pretty much useless in humid conditions, and Christmas Island was a tropical monsoon climate and very humid. So we had no record of radiation exposure.”

There were no long-term health studies of nuclear test veterans. Those who were there during the tests at Christmas Island were not given medical examinations when they left, and their health was not studied after they finished their service. Many servicemen – and many islanders – later reported severe health problems, which they believed where due to the radioactive fallout from nuclear bomb tests – from rare cancers to organ failure.

Some said they had fertility issues and difficulty conceiving, and many of those who did have children and grandchildren reported high incidences of birth defects, hip deformities, autoimmune diseases, skeletal abnormalities, spina bifida, scoliosis and limb abnormalities. Lax’s own health has been OK, but he does wonder about his children, who have both undergone surgery for a series of tumours, one at 14 years old.

Lax’s nuclear veteran friend has three types of cancer, which he says the specialist attributes “100 per cent to exposure to radiation”.

Another veteran, Doug Hern, who witnessed five thermonuclear explosions, says his skeleton is “crumbling” and has skin problems and bone spurs. His daughter died aged 13 from a cancer so rare that doctors didn’t have a name for it, and he believes all of this is due to the genetic effects of radiation exposure.

The Ministry of Defence (MoD) says it is grateful to Britain’s nuclear test veterans for their service, but maintains there is no valid evidence to link participation in these tests to ill health.

In 1983, the MoD did commission a study of more than 21,000 veterans, but – while the study found a slightly elevated risk of leukaemia – it concluded that the veterans had experienced no ill health as a result of their nuclear exposure. But nuclear veterans and their advocates have questioned the accuracy of the study.

For years, UK veterans have been campaigning with The British Nuclear Test Veterans Association, and Labrats – an organisation for nuclear test survivors – to be formally recognised, urging the Government to honour the nuclear test veterans’ service and sacrifice with an official recognition medal.

“I was a guinea pig,” says Lax, who believes he was placed there to see what would happen to people when the bomb went off.

The UK is the only nuclear power to deny special recognition and compensation to its bomb test veterans, of which there are estimated to be 1,500 surviving today.

In 2015, Fiji compensated all its veterans of British nuclear tests in the Pacific, with prime minister Frank Bainimarama announcing: “Fiji is not prepared to wait for Britain to do the right thing. We owe it to these men to help them now, not wait for the British politicians and bureaucrats.”

The United States Radiation Exposure Compensation Act has been providing compensation to its nuclear veterans since 1990.

Ed McGrath, 84, who was based at RAF Mildenhall in Suffolk, was 18 when he was sent to Australia and then flown to Maralinga to witness a test explosion.

At the Australian base camp we had good food and we had sunshine,” he tells i.

“As an 18 year-old, you’re travelling to places you can only imagine, but then when we were flown to witness the bombs, that’s where it went dark and nasty. They had the scientists and the engineers there, but I did nothing except stand there being told to put my hands over my eyes and turn my back to the blast. You were going up there to stand in the vicinity of a very powerful bomb 1,000 times more powerful than Hiroshima or Nagasaki.”

Despite persistent allegations by veterans that they had been used as guinea pigs in the tests, the Ministry of Defence denies this. McGrath is not convinced.

“There was no reason for us to be there, and I think the politicians who are responsible for sending us there must have come to the conclusion that, ‘Well, these lads are the price we’ve got to pay to find out what on earth is going on in the future.’

Veterans say that Boris Johnson recently at least gave them some hope of recognition, because as one of his last outings as Prime Minister, he met a group of veterans and campaigners and wrote in an open letter: “I’m determined that your achievements will never be forgotten. I have asked that we look again at the case for medallic recognition because it is my firm belief that you all deserve such an honour.”

Campaigners also showed the Prime Minister evidence that servicemen’s medical records from their time at the tests were missing from archives. Former prime minister Liz Truss, who promised to support their fight when she entered No 10, had not acted to put these promises into action. After she took office, she dismissed the veterans’ minister Johnny Mercer.

The Government’s Office for Veterans’ Affairs has this month announced it will launch a £250,000 oral history project to chronicle the voices and experiences of those who supported the UK’s effort to develop a nuclear deterrent. However, Lax says this is “too little, too late” and nowhere near what nuclear veterans should have.

McGrath has spent time worrying and feeling guilty that his family may face health problems because of his exposure to nuclear tests. His granddaughter had a brain tumour when she was a child but he says: “It’s very difficult to link the two directly and it’s not something you want to think about, to be honest.”

A Brunel University study found in 2021 that nuclear test veterans have double the normal levels of psychological stress for their age.

A survey and interviews by the Centre for Health Effects of Radiological and Chemical Agents found that most of the veterans report having become anxious in the mid-80s, when evidence first emerged of cancers, rare blood disorders, miscarriages in wives and birth defects in their children.

Yet this July, researchers at Brunel University published a study that showed “no significant increases in the frequency of newly arising genetic changes in the offspring of nuclear test veteran fathers. This result should reassure the study participants and the wider nuclear test veteran community.”

However, it seems that the legacy of nuclear testing has taken its toll in ways that we perhaps don’t yet fully understand, because there are communities of people across the world who feel their lives have been hugely affected by their nuclear veteran fathers and grandfathers.

Susan Musselwhite, 42, was eight when her father walked out on the family. When she saw him once again in her twenties, he said his leaving had all been down to the mental and physical anguish of being a test veteran on Christmas Island. Musslewhite lives with chronic migraines and Grave’s disease, sometimes barely being able to lift her head off the pillow, spending 90 per cent of her time indoors. “Sometimes I’m like an 80-year-old woman with dementia,” she says. She started to talk to other descendants and discovered that they were saying similar things about their mental and physical health. “I realised I wasn’t going through this alone. I truly believe that if my dad wasn’t at the test site, I wouldn’t be like this.”

Elin Doyle, an actress who has written a semi-autobiographical new play called Guinea Pigs about the tests’ generational effect, spent her early years witnessing her nuclear veteran father’s fight for justice. He had a rare form of cardiac sarcoidosis, an inflammatory condition that can result in heart rhythm abnormalities, in his forties. “Many years later,” says Doyle, “he was asked by a specialist whether he’d ever worked with radiation. So somebody else made the link and that was a bit of a shock for him. At that point I’d already had a sibling who was born with a birth defect.”

Doyle’s father died of heart failure in his sixties. “You can argue it’s because of radiation or not, but he didn’t have the sort of morbidities that would expose him to young heart disease, and we don’t have a history of it in the family, so the belief was that it was linked.”

Doyle also talks about the many of the veterans’ feelings of betrayal.

“Sending a bunch of 19-year-olds off in the 1950s to work on nuclear tests and assuring them that it’s perfectly safe, and then to find out actually, they probably weren’t safe and quite possibly, the powers that be knew that that was the case – that has an impact on the rest of a veteran’s life.”

Steve Purse, 47, from Denbighshire, Wales, remembers how his father David, an RAF flight lieutenant, was too scared to talk about his experience of being posted to test nuclear weapons in 1962 because of the Government secrecy around the nuclear mission.

He did, however, open up about it years later when he developed a skin condition over his arms and legs and the dermatologist asked whether he’d spent most of his life exposed to intense sunlight in the tropics. He said no, he had spent one year in Australia with nuclear tests. The dermatologist said that this was severe radiation damage to the skin.

Steve has a form of short stature, which doctors don’t know how to diagnose. “All they say is that I’m unique,” he says, “but my dad was exposed to alpha-radiation which causes mutation in DNA, so I believe it’s down to that. It feels like nuclear tests have left a legacy of genetic Russian roulette.”

For veteran McGrath, it feels as though the nuclear tests, and the men who were exposed to them, are a forgotten part of Cold War history. “It’s encouraging, though, that young people are beginning to take notice,” he says.

He did, however, open up about it years later when he developed a skin condition over his arms and legs and the dermatologist asked whether he’d spent most of his life exposed to intense sunlight in the tropics. He said no, he had spent one year in Australia with nuclear tests. The dermatologist said that this was severe radiation damage to the skin.

Steve has a form of short stature, which doctors don’t know how to diagnose. “All they say is that I’m unique,” he says, “but my dad was exposed to alpha-radiation which causes mutation in DNA, so I believe it’s down to that. It feels like nuclear tests have left a legacy of genetic Russian roulette.”

For veteran McGrath, it feels as though the nuclear tests, and the men who were exposed to them, are a forgotten part of Cold War history. “It’s encouraging, though, that young people are beginning to take notice,” he says.

Meetings scheduled on compensation for Utah’s ‘downwinders’ affected by nuclear testing

https://www.thespectrum.com/story/news/2022/10/24/meetings-scheduled-compensation-utahs-nuclear-downwinders/10588294002/ David DeMille, St. George Spectrum & Daily News,