If You Think Our Rulers Do Bad Things In Secret, Wait Til You See What They Do Out In The Open.

Caitlin Johnstone, Feb 09, 2026, https://www.caitlinjohnst.one/p/if-you-think-our-rulers-do-bad-things?utm_source=post-email-title&publication_id=82124&post_id=187345674&utm_campaign=email-post-title&isFreemail=true&r=1ise1&triedRedirect=true&utm_medium=email

They launched a live-streamed genocide in full view of the entire world.

They’re openly targeting civilian populations with siege warfare in Iran and Cuba in full view of the entire world.

They openly kidnapped the president of a sovereign nation in full view of the entire world.

They deliberately provoked a horrific and dangerous proxy war in Ukraine in full view of the entire world.

They spent years actively backing Saudi Arabia’s monstrous genocidal atrocities in Yemen in full view of the entire world.

They’re plundering and exploiting the resources and labor of the global south in full view of the entire world.

They’re killing the biosphere we all depend on for their own enrichment in full view of the entire world.

They’re circling the globe with hundreds of military bases to secure planetary domination in full view of the entire world.

They engage in nuclear brinkmanship and wave around armageddon weapons like pistols in full view of the entire world.

People go homeless and die of exposure while billionaires buy private islands and choose the next president in full view of the entire world.

Weapons manufacturers lobby for wars and then profit from the death and destruction they cause in full view of the entire world.

The president of the United States has repeatedly admitted to being bought and owned by the world’s richest Israeli in full view of the entire world.

The US Treasury Secretary has been repeatedly admitting that the US deliberately sparked the violence and unrest in Iran by methodically immiserating the population via economic warfare, in full view of the entire world.

I keep seeing people freaking out and asking how it’s possible that the individuals in the Epstein files haven’t been arrested for their secret nefarious behavior. And I always want to ask them, mate, have you seen the nefarious behavior they’re engaging in right out in the open?

Pay attention to the Epstein files. Pay attention to what little we can learn about how these freaks conduct themselves behind closed doors. By all means, pay close attention to these things.

But don’t forget to also pay attention to the far greater evils they are inflicting in full view of the entire world.

Without an economic reset with Russia, a peace deal for Ukraine may render Britain and Europe weakened relics of a unipolar past.

the peace deal available to Ukraine and also to its European sponsors, will never be as good as the one available today.

It won’t be as good as the deal that was available to Ukraine in April 2022 in Istanbul.

Fighting on for another year will simply stack the advantages more in favour of Russia such that any final settlement just gets progressively worse.

Ian Proud, Feb 09, 2026, https://thepeacemonger.substack.com/p/without-an-economic-reset-with-russia?utm_source=post-email-title&publication_id=3221990&post_id=187362231&utm_campaign=email-post-title&isFreemail=true&r=1ise1&triedRedirect=true&utm_medium=email

In recent days, I have seen more mainstream media commentators claiming that a peace deal can’t be agreed without Ukraine. But that is a statement of the blindingly obvious.

Of course, Ukraine must agree to the terms of any agreement.

But Russia must also agree to the terms of any agreement, and it has been the exclusion of Russia from any direct dialogue on ending the war which has led to the war dragging on for almost four years.

It seems an obvious thing to say, although not obviously clear to mainstream pundits, but a peace deal has to be agreed by both Russia and Ukraine.

This is a war that will not end with a decisive military victory by either side, with either Ukraine or Russia capitulating, even if Russia emerges in a stronger position, which appears likely.

Ultimately, the contours of any peace deal will represent that which both sides can live with, in terms of how they present peace to their publics.

But its detailed terms will reflect the relative weight of both sides in the final negotiation.

The one certainty in any peace deal is that Ukraine will become militarily unaligned, with NATO membership taken permanently off the table, in return for which it receives security guarantees that both it, and Russia, can accept.

There is simply no scenario I can see in which Ukraine continues on its path to NATO membership.

Deadlock on this issue, which Russia will not back down from, will lead to the continuation of the war, with Russia in a progressively stronger position militarily and better able to navigate the economic impacts than Ukraine, which is already bankrupt.

Britain and European will increasingly struggle to give Ukraine the resources that it needs, not just to fight, but also to avoid a shocking economic meltdown.

Everything else is in the peace plan will be down to fine points of detail and white noise.

But, of course, the terms of the peace deal will reflect the relative weight of both sides in the negotiations.

And let’s be clear that Russia continues to hold the stronger hand of cards in negotiations.

Russia will end the war with the strategic advantage on the battlefield, their army the most battle hardened and well equipped that it has been since the end of World War II.

Their core aim, to prevent NATO expansion in Ukraine will decisively have been achieved.

Russia will have managed the economic consequences of war better than Ukraine and its western sponsors, in particular Europe.

Ukraine will end the war, wanting to maintain an army of 800,000 but without the money to do so without British and Europeans donations of aid that will become harder to secure as peace sets it.

It will have failed to land NATO membership and the prospects for joining the EU might not be as bright as the Ukrainian population would expect.

It will be functionally bankrupt and will need quickly to reintroduce itself to a healthy relationship with western financial markets, in order to stay afloat.

However, the peace deal available to Ukraine and also to its European sponsors, will never be as good as the one available today.

It won’t be as good as the deal that was available to Ukraine in April 2022 in Istanbul. Fighting on for another year will simply stack the advantages more in favour of Russia such that any final settlement just gets progressively worse.

So, what is at stake?

Both sides will sign an agreement when they are satisfied that it meets their respective needs.

For Ukraine, that means a guarantee of not being attacked in the future, possibly accelerated membership of the EU, and provisions to help invest in post-war reconstruction. These represent basic requirements for its stability as a state, though not a strategic victory.

For Russia, by far the biggest requirement is that Ukraine is never able to join NATO in the future, which on its own will represent a huge strategic victory over the west.

These are central issues.

However, for Russia and also for Europe and Ukraine, an end to war may not deliver a genuinely normalised and enduring peace unless there is a normalisation of economic relationships, including but not limited to the lifting of economic sanctions.

A continued state of economic warfare would simply risk pressing the pause button on military warfare, at a time of European rearmament.

There would be little to motivate Russia to stop fighting in the first place, or to reduce its military readiness significantly following any armistice, if it believed that its economy would continue to be squeezed by the west, even though it has successfully navigated the economic shock of war better than Europe in particular.

On economics in particular, Russia will be concerned about Ukraine within Europe pushing for a maintenance of economic warfare against Russia, as it has since 2014, and as the Poles and Baltic States, not the mention the Brits, have done for many years.

Russia will also undoubtedly want issues such as the widespread cancellation of Russia from the international arena reversed, borders reopened, and readmittance to international sporting and cultural events.

So, even though the USA is in pole position in bringing both sides together in the negotiation process, it will be decisions in Europe that dictate whether any peace sticks.

And that raises questions about the role that the EU plays in the negotiation process.

Read more: Without an economic reset with Russia, a peace deal for Ukraine may render Britain and Europe weakened relics of a unipolar past.Until now, the European Union and Britain have proved themselves singularly unwilling to enter into direct dialogue with Russia to end the war, adding to the sense that they are invested in its continuance.

Efforts in Europe to agree a lead negotiator with Russia have so far come to nothing.

It is therefore right that the US has mediated the talks between Russia and Ukraine, and for this President Trump must take the credit, as without initiative it would not have happened.

However, that poses risks, that the US will not be able to leverage EU policy towards Russia and include in any peace deal clauses that depend on European agreement.

And US leverage over Europe may have been weakened by its posture towards the future status of Greenland.

It does therefore make sense rationally for the Europeans to be introduced into the peace process at some stage.

Even if not in the main bilateral part of the talks between Russia and Ukraine, there may need to be a process in which the USA, perhaps directly with Europe, negotiates the contours of a unified economic off-ramp from a war that Ukraine and Russia have agreed bilaterally to bring to a halt.

Hitherto, the Europeans have been unable to coordinate on who this should be involved in negotiations, and the Russians clearly don’t want it to be Kaja Kallas, who has shown herself set against any peace deal to end the war, setting unrealistic conditions that she is not in a position to enforce on Russia.

Based on the evidence so far, the Europeans will need for the first time to reimagine their role as an external party to the conflict, having to date, positioned themselves directly as a party to the conflict, through military, political and financial support to Ukraine, and a stated strategy to defeat Russia.

That means both a commitment to integrate and support Ukraine into the Union and to normalise relations with Russia, both of which are more complex tasks that sending money to Ukraine to keep fighting.

This may prove almost as difficult a task as obtaining bilateral agreement between the combatants themselves to end the fighting, given the lack of clear and decisive leadership within Europe itself. It is hard to see Ursula von der Leyen playing the peace maker role. Will it be the leader or a group of leaders from Member States? And would it, in fact, make sense to include a small group of leaders, including from Central European States like Hungary, who have long opposed unconditional support for Ukraine and for the war? What role would Britain play, sitting outside of the EU, and having been one of the biggest advocates for the continuation of the war?

These are hugely complicated, and I am not confident that a decisive position will be reached soon, not least given the months it has taken already to discuss the basics of who might engage in direct dialogue with President Putin.

At the same time, the Europeans risk being even further sidelined in the process if they refuse to engage, which may force them to commit to a meaningful role in peace talks which they have hitherto ruled themselves out of.

One of the most fascinating aspects of the peace process is how it will finally be agreed and signed.

Zelensky has appeared for many months determined to sign off an any agreement through a direct meeting with President Putin.

It is entirely normal for Heads of State to meet to sign off landmark treaties and peace deals. After World War II, the surrender of both Germany and Japan was signed off by more junior figureheads, but Ukraine will not be surrendering.

It might not seem immediately obvious why Zelensky should want to meet Putin, having spent the whole war encouraging Russia’s isolation on the world stage.

Yet here the optics appear more about Zelensky’s desire to legitimise his role as President, in circumstances where he hasn’t faced an election since 2019.

Knowing that an end to the war will usher in Presidential elections in Ukraine, signing a peace deal may epitomise his desire to present himself to Ukrainian citizens as a peace maker, with one eye on boosting his popularity before elections.

I personally think that even if he meets Putin, Zelensky is probably still doomed to lose a future Presidential poll, because any deal he signs will be worse than the deal that was available to him in April 2022 in Istanbul.

Putin will also not want to give Zelensky a gift of free publicity and in any case will be concerned that Zelensky will simply try to pull a publicity stunt if he meets Putin. In any case, I don’t see such a hypothetical meeting taking place without Trump who wants to position himself as the ultimate peacemaker. And Putin will want to keep President Trump on side with one eye on a much bigger and more valuable to Russia reset in economic relations with America.

So, I don’t think Putin would see it in his interests to make not meeting Zelensky a red line issue, so long as Trump committed to making sure the choreography of the event was proper.

He will in any case know that he has a stronger claim to victory coming out of the war than Zelensky.

He will be seen by Russian people as the President who stared down NATO and prevented its expansion, weakening the perception of western hegemony among countries in the developing world, and sowing serious division within the European Union.

Zelensky, in the cold light of day, will be seen as the President who settled for a worse deal than that which was available to him in April 2022. And even if the prospect of EU membership is accelerated, it is unlikely that Ukraine will be allowed to join as an equal member and will have bankrupted and depopulated itself for the right to second class citizenship.

Both countries will have lost very large numbers of troops to death or injury. Russia will reach back into history to justify this on the basis of fending off an existential threat to its nation in the guise, not of Ukraine itself, but of the NATO military alliance.

Ukrainian leaders will have to explain why so many men and women died or were injured to bring about a less favourable peace to that which was available in Istanbul four years earlier, and that will be a harder case to make

But when it comes down to it, no one really wins in a war, and primarily ordinary working people suffer.

Which again serves as a reminder that wars are often judged in hindsight on their political aftermath.

The Second World War decisively signalled the end of the British Empire leaving only two in its place, the United States and the Soviet Union.

Ukraine will emerge from this war significantly weakened against a Russia that has renewed standing in the developing world. There is a significant chance that the Euro-integration project will have reached its high-water mark and, like the British Empire, will also go into decline.

The end of the war in Ukraine will decisively usher in a more multi-polar world, in which Europe and Britain are seen as weakened relics of a unipolar past.

Selective context: Why Isaac Herzog’s visit deepens Australia’s moral failure

It would be hard to imagine a more divisive guest in this country. The Jewish Council of Australia has expressed ‘outrage that the Albanese Government would fuel the flames of division by inviting Herzog to visit Australia, warning that his trip is completely inappropriate and offensive and will rightly spark mass protest’. Herzog, the Council said, ‘has played an active role in the ongoing destruction of Gaza, including the murder of tens of thousands of Palestinians and the displacement of millions’.

By Sue Wareham | 9 February 2026, https://independentaustralia.net/politics/politics-display/selective-context-why-isaac-herzogs-visit-deepens-australias-moral-failure,20660

Calls to ‘consider the context’ of President Herzog’s visit obscure Israel’s ban on dozens of NGOs in Gaza and the West Bank, writes Dr Sue Wareham.

AHEAD OF TODAY’S VISIT to Australia by Israeli President Isaac Herzog and the anticipated large protests against it, Foreign Minister Penny Wong asked us to ‘consider the context’ of the visit.

Part of that context is the horrific massacre of 15 Jewish Australians at Bondi in December and the deep sense of grief felt throughout Jewish communities and beyond.

However, the context also includes the destruction by Israel of practically every aspect of civilian society in Gaza, with over ten per cent of the population directly killed or injured since October 2023 and barely a soul alive who has not been traumatised in multiple ways, including bereavement, displacement, and deprivation of food, clean water, sanitation, shelter and other essentials.

Herzog is not an innocent bystander, as Israel’s breaches of international law in Gaza and the West Bank have become so commonplace as to be almost normalised. In September 2025, the United Nations Commission of Inquiry on the Occupied Palestinian Territory accused him of inciting genocide, citing his statement that “It’s an entire nation out there that is responsible”, made soon after Hamas’ brutal attacks of 7 October 2023. The entire Palestinian population has been punished ever since.

That collective punishment has deeply affected very many Palestinian Australians, as they grieve the loss of loved ones in Gaza, and have watched helplessly as remaining loved ones have faced deprivation, multiple displacements and a dire humanitarian situation.

Despite the “ceasefire” that began in early October 2025 (a ceasefire which appears to mean fewer bombs rather than no bombs), the collective punishment continues.

Israeli authorities have now de-registered and are effectively banning 37 international humanitarian organisations (INGOs) from operating in Gaza and the West Bank. Unless the organisations comply with Israeli demands to provide personal data on all their staff – in a context where over 500 humanitarian workers have been killed in Gaza since 7 October 2023 – they will have to withdraw from all the Occupied Palestinian Territory by the start of March.

This poses an impossible choice for INGOs — to either compromise staff safety or to abandon people who are in desperate need. Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), as one of the affected agencies, has made the extremely painful decision that it will not comply with Israeli demands for staff information. MSF’s statement of 30 January said that ‘despite repeated efforts, it became evident in recent days that we were unable to build engagement with Israeli authorities on the concrete assurances [regarding staff safety] required’.

MSF states that if the agency is expelled from Gaza and the West Bank, ‘it would have a devastating impact, as Palestinians face a brutal winter amidst destroyed homes and urgent humanitarian needs’ with basic services including food, water, shelter, healthcare, fuel and livelihoods largely destroyed, and a health system that is ‘nearly non-functional’.

Oxfam’s assessment of 3 January is similar, stating that ‘Despite the ceasefire, humanitarian needs remain extreme’. The removal of these services would ‘close health facilities, halt food distributions, collapse shelter pipelines and cut off life-saving care’.

Oxfam noted that INGOs already operate according to strict compliance and due diligence standards.

Setting aside any moral imperative to provide aid for fellow humans who are suffering, Israel’s actions in banning INGO access violate the nation’s legal obligations, as the occupying force, to ensure the health and welfare of the civilian population.

They also violate the January 2024 International Court of Justice ruling that Israel ‘must take immediate and effective measures to enable the provision of urgently needed basic services and humanitarian assistance to address the adverse conditions of life faced by Palestinians in the Gaza Strip’.

Far from complying with the law, Israel continues to actively block the delivery of essential aid to a population in urgent need, and is now enforcing INGO registration conditions that exceed routine oversight and undermine humanitarian neutrality and independence.

For the many Palestinian Australians and their loved ones in Gaza, Israel’s actions have devastating consequences. And yet their grief and distress are not part of Minister Wong’s selective “context” for the visit of President Herzog.

It would be hard to imagine a more divisive guest in this country. The Jewish Council of Australia has expressed ‘outrage that the Albanese Government would fuel the flames of division by inviting Herzog to visit Australia, warning that his trip is completely inappropriate and offensive and will rightly spark mass protest’. Herzog, the Council said, ‘has played an active role in the ongoing destruction of Gaza, including the murder of tens of thousands of Palestinians and the displacement of millions’.

Australia’s stance could have been very different. Apart from choosing our guests more sensitively and avoiding those accused of the most grievous crimes, Australia should long since have applied meaningful sanctions against Israeli individuals and the State of Israel itself.

Foreign Minister Wong has the power to determine that Israel’s ongoing deliberate obstruction of aid and its collective punishment of the Palestinian people meet the threshold of “serious violation or abuse” under Australia’s sanctions regime. She has chosen instead to insulate Israel from accountability, thus undermining the universality of international law and eroding Australia’s credibility as an independent nation.

The people of Palestine and their loved ones here pay a heavy price for Australia’s failure to act.

Sanctions against Israel are not likely to be announced in the coming days, but the need for them is only growing.

Residential proximity to nuclear power plants and cancer incidence in Massachusetts, USA (2000–2018)

18 December 2025, Springer Nature, Volume 24, article number 92, (2025)

“………………………………………. Results

Proximity to plants significantly increased cancer incidence, with risk declining by distance. At 2 km, females showed RRs of 1.52 (95% CI: 1.20–1.94) for ages 55–64, 2.00 (1.59–2.52) for 65–74, and 2.53 (1.98–3.22) for 75 + . Males showed RRs of 1.97 (1.57–2.48), 1.75 (1.42–2.16), and 1.63 (1.29–2.06), respectively. Cancer site-specific analyses showed significant associations for lung, prostate, breast, colorectal, bladder, melanoma, leukemia, thyroid, uterine, kidney, laryngeal, pancreatic, oral, esophageal, and Hodgkin lymphoma, with variation by sex and age. We estimated 10,815 female and 9,803 male cancer cases attributable to proximity, corresponding to attributable fractions of 4.1% (95% CI: 2.4–5.7%) and 3.5% (95% CI: 1.8–5.2%).

Conclusions

Residential proximity to nuclear plants in Massachusetts is associated with elevated cancer risks, particularly among older adults, underscoring the need for continued epidemiologic monitoring amid renewed interest in nuclear energy. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1186/s12940-025-01248-6

Trump is not threatening war on Iran over its nuclear program, but because it challenges U.S. dominance.

In short, it is about removing Iran from the strategic playing field, as it is the sole actor in the region that is powerful, influential, and beyond the United States’ direct control. The U.S. and Israel desperately want to remove that oppositional force.

So Trump is buying time by agreeing to talks that cannot succeed on the terms he and Rubio have laid down. He is likely to use that time to magnify the threat against the Iranian leadership in the vain hope that they will acquiesce to his demands.

The U.S. is once again threatening a war on Iran that could devastate the region. Trump knows Iran is not pursuing nuclear weapons, but that has never been the point. It is about removing Iran as the only actor in the region beyond U.S. control.

By Mitchell Plitnick February 6, 2026, https://mondoweiss.net/2026/02/trump-is-not-threatening-war-on-iran-over-its-nuclear-program-but-because-it-challenges-u-s-dominance/

American and Iranian negotiators are meeting in Muscat to see if they can come to an agreement and avoid an American attack on Iran. The chances don’t look good.

There was some initial hope because Donald Trump agreed to hold talks at all. The buildup of American forces in the region and the frequent planning meetings with Israeli political and military officials gave the appearance of an unstoppable buildup to war.

But American allies Türkiye, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and Oman have been working hard to convince Trump not to attack Iran. They fear the potential backlash of an American attack on the Islamic Republic, believing that Iran is not likely to respond to an attack with the restraint they have shown in the past.

Israel is urging Trump to attack, as the government of Benjamin Netanyahu is the one entity that stands to benefit from the chaos that an attack on Iran could bring.

Indeed, Iran has warned that an attack this time will be met with a very different response than previous ones. Yet, paradoxically, it is the very fact that Iran is capable of a more damaging response than it has taken in the past that creates the impasse that is likely to derail negotiations.

What each side wants

Iran’s desires from any talks with the U.S. are straightforward: they want the U.S. to stop threatening to attack, and to lift the sanctions that have helped to cripple Iran’s economy.

But the United States has more complicated demands.

- The United States wants Iran to completely abandon nuclear power. This demand is not just about weaponry, but includes all civilian nuclear power under Iran’s control. No uranium at all can be enriched by Iran, regardless of whether it is for civilian or military purposes, and all enriched uranium Iran has must be handed over.

- The U.S. is demanding that Iran agree to limits dictated by Washington on the range and number of ballistic missiles it can possess.

- The U.S. is demanding that Iran end its support of any and all armed resistance groups in the region.

All of these demands are unreasonable. But the United States is holding a loaded gun to Iran’s head. The U.S. has moved a large carrier group into the waters near Iran, and between American and Israeli intelligence, they surely have a very clear map of where they want to strike to go along with the technical capability to essentially ignore Iran’s defenses.

But while Iran can do very little to shield itself from an American or Israeli attack, it is capable of responding to one. That is what the last two American demands are focused on, and it’s really the reason all of this is happening.

If the U.S. or Israel attacks Iran and Iran elects to respond with all of its capabilities—which it has not done in previous attacks—it has the ability to kill many American soldiers, severely disrupt oil production in the Gulf, or cause significant damage to Israel.

Iran can do this because it has a large battery of long-range ballistic missiles. It has already shown, last June, that it can hurt Israel, and that was an attack largely meant to be a warning.

Iran also backs various militias in the region, some large, like Ansar Allah in Yemen, others smaller. That means it can launch guerrilla attacks on American bases or other key sites in places like Iraq and Syria.

Iran can also target oil fields throughout the region, either with missiles or drones or with militia attacks. That’s a major reason Trump’s friends in the Gulf are reluctant to see him start a war.

The ability to do all of that gives Washington pause. Donald Trump likes it when he can do quick operations with little or no pushback, as he did recently in Venezuela or last year in Iran. Trump has carefully avoided situations where American soldiers might be killed. Iran might not let the U.S. off so easily this time around.

The reality behind U.S. demands

That brings us to why talks are so unlikely to succeed.

Iran has already made it clear it has no intention to negotiate on their support for groups throughout the region or on their ballistic missile arsenal. They understand that the reason the United States is trying to force them to agree to such measures is that it would leave Iran defenseless. Giving in to these demands would be tantamount to national suicide.

The Iranian leadership is more than happy to discuss the issue of nuclear power. As unfair as the terms might be, they might even be willing to reach a compromise that allows them to use nuclear power without enriching uranium themselves. That’s far from ideal, but Iran is facing a considerable threat.

But this holds little interest for the Trump administration. Despite American chest-thumping, they know that Iran is not pursuing a nuclear weapon, nor were they before the U.S. damaged so much of their nuclear infrastructure last year. Trump’s own intelligence corps confirmed that Iran was not actively seeking a nuclear weapon, just as it had affirmed that finding every year since 2007.

But none of this has ever been about an Iranian nuclear weapon. Rather, it has always been about pressuring the Islamic Republic either to fall or to radically change its behavior in the region. It has always been about getting Iran to stop supporting the Palestinian cause rhetorically and to stop arming Palestinian factions. It has always been about stopping Iran from supporting militias in the region that act outside of the American-run system, unlike those that are backed by Saudi Arabia, the UAE, or other states in the region that are on good terms with Washington.

In short, it is about removing Iran from the strategic playing field, as it is the sole actor in the region that is powerful, influential, and beyond the United States’ direct control. The U.S. and Israel desperately want to remove that oppositional force.

Trump weighs the consequences of attacking Iran

Does Trump really want a war? That concern with Iran is a long-term U.S.-Israeli policy goal. What Donald Trump personally wants is always difficult to know. It can change from day to day, and is often based on a less-than-full understanding of the real world.

From all appearances, Trump felt emboldened by the American success in Venezuela. He kidnapped the head of state and his wife, and suffered no American casualties in doing so. The short-term political backlash, both in Latin America and in the U.S., was brief and minimal.

No doubt, he envisioned a similar success in Iran, when the protests there and the Iranian government’s brutal response helped to create what might have looked superficially like similar circumstances. Trump began issuing one threat after another, and while their frequency has been intermittent, they have not stopped.

But his friends in Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Türkiye, and elsewhere in the Mideast explained to Trump that the outcome in Iran would be very different from that in Venezuela. Iran has the capabilities we’ve already discussed here, but there are other key differences.

For one, Iran has a deep governmental infrastructure, and there is no one in it who is both capable of taking over from Ayatollah Ali Khamenei and willing to compromise with Trump in the way Delcy Rodriguez has in Caracas. Despite the occasional protester in Iran calling out the name of Reza Pahlavi, the son of the last Shah of Iran, who was deposed in 1979, there is no infrastructure of support for him in Iran, and it would likely be impossible to simply install him without a full-scale invasion of the country.

So Trump is buying time by agreeing to talks that cannot succeed on the terms he and Rubio have laid down. He is likely to use that time to magnify the threat against the Iranian leadership in the vain hope that they will acquiesce to his demands.

But the primary purpose of that time is to continue to position American and Israeli forces to counter what they can anticipate of an Iranian response. That would mean not just the stationing of ships in striking distance of Iran, but also positioning whatever military assets they might have in countries like Iraq and Syria, as well as in other Gulf states, to counter guerrilla attacks by Iran-aligned militias and getting friendly states to agree to help with shooting down Iranian missiles and drones, as they did last year.

With Rubio and Benjamin Netanyahu pushing Trump toward a regime change war with Iran, and given the amount of bluster he has already put out there, it is hard to see Trump backing away from a war if Iran will not agree to compromise on its missiles and the militias it supports. And Iran is not about to do that.

The war that will ensue stands a good chance of toppling the Iranian government, but with nothing to replace it, the power vacuum that will surely follow will mean chaos not only for Iran but for the whole region. That isn’t really in Trump’s interests, and it certainly does not benefit his Gulf Arab allies.

Netanyahu, on the other hand, will have made the “neighborhood” that much more dangerous just as Israel’s election season begins to ramp up. While many Israelis have lost faith that “Mr. Security” can protect them after October 7, a heightened sense of danger to Israelis remains the atmosphere that is most favorable to Netanyahu electorally. It’s therefore no surprise that Israel is the one actor in the region that is pressing for this regime change war.

Averting that war will mean the Trump administration climbing down from its maximalist demands. There are indications that the U.S. is looking, at least,for an option that allows it to do that without appearing to have shied away from Iranian retaliation. But that remains an unlikely outcome, as hawks in Israel, Washington, and among the anti-regime exile Iranian community continue to urge an attack.

Eight Decades Later, It Remains One World or None

“The bombs will never again, as in Japan, come in ones or twos. They will come in hundreds, even in thousands.” And given the effect of radiation, those who made “remarkable escapes,” the “lucky” ones, would die all the same. Imagining a prospective strike on New York City, he wrote of the survivors who “died in the hospitals of Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Rochester, and Saint Louis in the three weeks following the bombing. They died of unstoppable internal hemorrhages… of slow oozing of the blood into the flesh.” Ultimately, he concluded, “If the bomb gets out of hand, if we do not learn to live together… there is only one sure future. The cities of men on earth will perish.”

By Eric Ross, February 8, 2026, https://tomdispatch.com/eight-decades-later-it-remains-one-world-or-none/

On February 5th, with the expiration of the New Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty, or New START, the only bilateral arms control treaty left between the United States and Russia, we are guaranteed to find ourselves ever closer to the edge of a perilous precipice. The renewed arms race that seems likely to take place could plunge the world, once and for all, into the nuclear abyss. This crisis is neither sudden nor surprising, but the predictable culmination of a truth that has haunted us for nearly 80 years: humanity has long been living on borrowed time.

In such a context, you might think that our collective survival instinct has proven remarkably poor, which is, at least to a certain extent, understandable. After all, if we had allowed ourselves to feel the full weight of the nuclear threat we’ve faced all these years, we might indeed have collapsed under it. Instead, we continue to drift forward with a sense of muted dread, unwilling (or simply unable) to respond to the nuclear nightmare. In a world already armed with thousands of omnicidal weapons, such fatalism — part suicidal nihilism and part homicidal complacency — becomes a form of violence in its own right.

Given such indifference, we risk not only our own lives but also the lives of all those who would come after us. As Jonathan Schell observed decades ago, both genocide and nuclear war are distinct from other forms of mass atrocity in that they serve as “crimes against the future.” And as Robert Jay Lifton once warned, what makes nuclear war so singularly horrifying is that it would constitute “genocide in its terminal form,” a destruction so absolute as to render the earth unlivable and irrevocably reverse the very process of creation.

Yet for many, the absence of such a nuclear holocaust, 80 years after the U.S. dropped atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, is taken as proof that such a catastrophe is, in fact, unthinkable and will never happen. These days, to invoke the specter of annihilation is to be dismissed as alarmist, while to argue for the abolition of such weaponry is considered naïve. As it happens, though, the opposite is true. It’s the height of naïveté to believe that a global system built on the supposed security of nuclear weapons can endure indefinitely.

That much should be obvious by now. In truth, we’ve clung to the faith that rational heads will prevail for far too long. Such thinking has sustained a minimalist global nonproliferation regime aimed at preventing the further spread of nuclear weapons to so-called terrorist states like Iraq, Libya, and North Korea (which now indeed has a nuclear arsenal). Yet, today, it should be all too clear that the states with nuclear weapons are, and have long been, the true rogue states.

A nuclear-armed Israel has, after all, been committing genocide in Gaza and has bombed many of its neighbors. Russia continues to devastate Ukraine, which relinquished its nuclear arsenal in 1994, and its leader, Vladimir Putin, has threatened to use nuclear weapons there. And a Washington led by a brazen authoritarian deranged by power, who has declared that he doesn’t “need international law,” has stripped away the fragile façade of a rules-based global order.

Donald Trump, Vladimir Putin, and the leaders of the seven other nuclear-armed states possess the unilateral capacity to destroy the world, a power no country should be allowed to wield. Yet even now, there is still time to avert catastrophe. But to chart a reasonable path forward, it’s necessary to look back eight decades and ask why the world failed to ban the bomb at a moment when the dangerous future we now inhabit was already clearly foreseeable.

Every City is Hiroshima

With Hiroshima and Nagasaki still smoldering ruins, people everywhere confronted a rupture so profound that it seemed to inaugurate a new historical era, one that might well be the last. As news of the atomic bombings spread, a grim consensus took shape that technological “progress” had outpaced political and moral restraint. Journalist Norman Cousins captured the zeitgeist when he wrote that “modern man is obsolete, a self-made anachronism becoming more incongruous by the minute.” Human beings had clearly fashioned themselves into vengeful gods and the specter of Armageddon was no longer a matter of theology but a creation of modern civilization.

In the United States, of course, a majority of Americans greeted the initial reports of the atomic bombings of those two Japanese cities in a celebratory fashion, convinced that such unprecedented weapons would bring a swift, victorious end to a brutal war. For many, that relief was inseparable from a lingering desire for retribution. In announcing the first atomic attack, President Harry Truman himself declared that the Japanese “have been repaid many fold” for their strike on Pearl Harbor, which inaugurated the official American entry into World War II. Yet triumph quickly gave way to a more somber reckoning.

As the scale of devastation came into fuller view, the psychological fallout radiated far beyond Japan. The New York Herald Tribune captured a growing unease when it editorialized that “one forgets the effect on Japan or on the course of the war as one senses the foundations of one’s own universe trembling a little… it is as if we had put our hands upon the levers of a power too strange, too terrible, too unpredictable in all its possible consequences for any rejoicing over the immediate consequences of its employment.”

Some critics of the bombings would soon begin to frame their concerns in explicitly moral terms, posing the question: Who had we become? Historian Lewis Mumford, for example, argued that the attacks represented the culmination of a society unmoored from any ethical foundations and nothing short of “the visible insanity of a civilization that has ceased to worship life and obey the laws of life.” Religious leaders voiced similar concern. The Christian Century magazine typically condemned the bombings as “a crime against God and humanity which strikes at the very basis of moral existence.”

As the apocalyptic imagination took hold, others turned to a more self-interested but no less urgent question: what will happen to us? Newspapers across the country began running stories on what a Hiroshima-sized bomb would do to their downtowns. Yet Philip Morrison, one of the few scientists to witness both the initial Trinity Test of the atomic bomb and Hiroshima after the bombing, warned that even such terrifying projections underestimated the danger.

Deaths in the hundreds of thousands were, he insisted, far too optimistic. “The bombs will never again, as in Japan, come in ones or twos. They will come in hundreds, even in thousands.” And given the effect of radiation, those who made “remarkable escapes,” the “lucky” ones, would die all the same. Imagining a prospective strike on New York City, he wrote of the survivors who “died in the hospitals of Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, Rochester, and Saint Louis in the three weeks following the bombing. They died of unstoppable internal hemorrhages… of slow oozing of the blood into the flesh.” Ultimately, he concluded, “If the bomb gets out of hand, if we do not learn to live together… there is only one sure future. The cities of men on earth will perish.

One World or None

Morrison wrote that account as part of a broader effort, led by former Manhattan Project scientists who had helped create the bomb, to alert the public to the newfound danger they themselves had helped unleash. That campaign culminated in the January 1946 book One World or None (and a short film). The scientists had largely come to believe that, if the public had their consciousness raised about the implications of the bomb, a task for which they felt uniquely responsible and equipped, then public opinion might shift in ways that could make policies capable of averting catastrophe politically possible.

Scientists like Niels Bohr began calling on their colleagues to face “the great task lying ahead,” while urging them to be “prepared to assist in any way… in bringing about an outcome of the present crisis of humanity worthy of the ideals for which science through the ages has stood.” Accepting such newfound social responsibility felt unavoidable, even if so many of those scientists wished to simply return to their prewar pursuits in the insulated university laboratories they once inhabited.

As physicist Joseph Rotblat observed, among the many forms of collateral damage inflicted by the bomb was the destruction of “the ivory towers in which scientists had been sheltering.” In the wake of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, that rupture propelled them into public life on an unprecedented scale. The once-firm boundary between science and politics began to blur as formerly quiet and aloof researchers spoke to the press, delivered public lectures, published widely circulated articles, and lobbied members of Congress in an effort to secure some control over atomic energy.

Among them was J. Robert Oppenheimer, director of the Los Alamos Laboratory where the bomb was created, who warned that, “if atomic bombs are to be added as new weapons to the arsenals of a warring world… then the time will come when mankind will curse the names of Los Alamos and Hiroshima,” a statement that left some officials perplexed. Former Vice President Henry Wallace, who had known Oppenheimer as both the director of Los Alamos and someone who had directly sanctioned the bombings, recalled that “he seemed to feel that the destruction of the entire human race was imminent,” adding, “the guilt consciousness of the atomic bomb scientists is one of the most astounding things I have ever seen.”

Yet the scientists pressed ahead in their frantic effort to avert future catastrophe by preventing a nuclear arms race. They insisted that there was no doubt the Soviet Union and other powers would acquire the weapon, that any hope of a prolonged atomic monopoly was delusional, and that espionage was incidental to such a reality, since the fundamental scientific principles needed to build an atomic bomb had been established by 1940. And with Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the secret that a functioning bomb was possible was obviously out.

They argued that there would be no effective defense against a devastating atomic attack and that the U.S., as a highly urbanized society, was uniquely vulnerable to such “city killer” weapons. With vast, exposed coastlines, they warned that such a bomb, not yet capable of being delivered by a missile, could simply be smuggled into one of the nation’s ports and lie dormant there for years. For the scientists, the implications were unmistakable. The age of national sovereignty had ended. The world had become too dangerous for national chauvinism, which, if humanity were to survive, had to give way to a new architecture of international cooperation.

Teaching Us to Love the Bomb

Such activism had its intended effects. Many Americans became more fearful and wanted arms control. By late 1945, a majority of the public consistently supported some form of international control over such weaponry and the abolition of the manufacturing of them. And for a brief moment, such a possibility seemed within reach. The first resolution passed by the new United Nations in January 1946 called for exactly that. The publication of John Hersey’s Hiroshima first as a full issue of the New Yorker and then as a book, with its intense portrayal of life and death in that Japanese city, further shifted public sentiment toward abolition.

Yet as such hopes crystallized at the United Nations, the two global superpowers, the United States and the Soviet Union, were already preparing for a future nuclear war. Washington continued to expand its stockpile of atomic weaponry, while Moscow accelerated its work creating such weaponry, detonating its initial atomic test four years after the world first met that terrifying new weapon. That Soviet test, followed by the Korean War, helped extinguish the early promise of an international response to such weaponry, a collapse aided by deliberate efforts in Washington to ensure that the United States grew its atomic arsenal.

In that effort, former Secretary of War Henry Stimson was coaxed out of retirement by President Truman’s advisers who urged him to write one final, “definitive” account defending the bombings to neutralize growing opposition. As Harvard president and government-aligned scientist James Conant explained to Stimson, officials in Washington feared that they were losing the ideological battle. They were particularly concerned that mounting anti-nuclear sentiment would prove persuasive “among the type of person that goes into teaching,” shaping a generation less inclined to regard their decision as morally legitimate.

Stimson’s article, published in Harper’s Magazine in February 1947, helped cement the official narrative: that the bomb was a last resort rooted in military necessity that saved half a million American lives and required neither regret nor moral examination. In that way, the opportunity to ban the bomb before the arms race took off was squandered not because the public failed to recognize the threat, but because the government refused to heed the will of its people. Instead, it sought to secure power through nuclear weapons, driven by a paranoid fear of Moscow that became a self-fulfilling prophecy. What followed were decades of preemptive escalation, the continued spread of such weaponry globally, and, at its height, a global arsenal of more than 60,000 nuclear warheads by 1985.

Forty years later, in a world where nine countries — the U.S., Russia, China, France, Great Britain, India, Pakistan, Israel, and North Korea — already have nuclear weapons (more than 12,000 of them), there can be little doubt that, as things are now going, there will be both more countries and more weapons to come.

Such a global arms race must, however, be ended before it ends the human race. The question is no longer what is politically possible, but what is virtually guaranteed if we refuse to pursue the “impossible.” Nuclear weapons are human creations and what is made by us can be dismantled by us. Whether that happens in time is, of course, the question that now should confront everyone, everywhere, and one that history, if there is anyone around to write or to read it, will not excuse us for failing to answer.

The risk of nuclear war is rising again. We need a new movement for global peace.

This enormous nuclear construction program is euphemistically termed “modernization” in Washington. It is more properly understood as a vast program for enhancing the capacity to use nuclear weapons.

With the end of the New Start treaty, we face a potentially catastrophic arms race. It can still be prevented

David Cortright, 9 Feb 26, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2026/feb/08/nuclear-war-risk-rising-global-peace

The risk of nuclear war is greater now than in decades – and rising. The Bulletin of Atomic Scientists recently set its famous Doomsday Clock closer to midnight, indicating a level of risk equivalent to the 1980s, when US and Soviet nuclear stockpiles were increasing rapidly. In those years, massive waves of disarmament protest arose in Europe and the United States. Political leaders responded, the cold war ended and many people stopped worrying about the bomb.

Today, the bomb is back. Political tensions are rising, and nuclear weapons have spread to other countries, including Israel, India, Pakistan and North Korea. China is rapidly increasing its nuclear arsenal. The US-Russia arms competition may accelerate soon with the expiration on 5 February of the last remaining arms control agreement, the New Start treaty. To prevent the growing nuclear threat, we need a new global peace movement.

Donald Trump had a chance to prevent nuclear escalation in the months preceding the expiration of New Start. The Russian president, Vladimir Putin, offered to voluntarily maintain the limits established by the treaty and invited the US to follow suit, but the White House refused. The administration has proposed instead to negotiate an entirely new strategic arms treaty, a process that could take years.

Political leaders and security experts talk about nuclear weapons as if they are mere pieces on a chessboard, to be brandished and maneuvered for strategic advantage. We are told that nuclear weapons are necessary for peace, but there can be no genuine peace if security rests on the threat of using instruments of indiscriminate mass annihilation. One large bomb detonated over a modern city could kill millions of people from the catastrophic blast and the spread of genetically damaging radioactive fallout. Research estimates that a nuclear war between the US and Russia could kill up to 5 billion people.

Nuclear deterrence does not create peace. It has not prevented major wars, by Russia in Ukraine, or by the US in Iraq and Vietnam. The number of armed conflicts in the world today is at an all-time high. The supposed deterrent effect of nuclear weapons lacks credibility. Deterrence is achievable by non-nuclear means, the scholar Mary Kaldor reminds us. Wars can be avoided by strengthening mechanisms of global cooperation and applying proven methods of conflict prevention and peacemaking diplomacy.

Current leaders in Washington ignore these realities and are pushing ahead with a massive weapons upgrade, at a cost of trillions of dollars. The US is creating an entirely new fleet of land-based intercontinental ballistic missiles, new ballistic missile-firing submarines, updated strategic aircraft and air-launched cruise missiles, a new system of sea-launched nuclear cruise missiles, and enormous new facilities to produce plutonium components for an estimated 80 new nuclear warheads per year.

This enormous nuclear construction program is euphemistically termed “modernization” in Washington. It is more properly understood as a vast program for enhancing the capacity to use nuclear weapons. “A nuclear war can never be won and should never be fought,” the then US president, Ronald Reagan, and Soviet leader, Mikhail Gorbachev, memorably declared in the 1980s. Political leaders often repeat the phrase, but their actions betray their words.

Nuclear arms control agreements traditionally provided guardrails against unconstrained arms racing, but those protections have been discarded in recent decades and are gone completely now with the expiration of the New Start treaty. In the absence of agreed weapons restrictions, US and Russian officials could deploy hundreds of warheads in the coming months.

An accelerated arms race can still be prevented if the US would agree to maintain current weapons limits as it pursues potential negotiations. Moscow expressed regret that Washington did not accept its offer to maintain weapons restrictions, but it did not withdraw the proposal. The deal could still be on the table.

All that’s needed is for the White House to state that the US will not exceed current strategic weapons limits as long as the Kremlin agrees to exercise similar restraint. This small but important mutual step could reduce the near-term threat of nuclear escalation. It could open political space for more fundamental change.

An agreement to refrain from weapons increases would create a positive atmosphere for negotiating a new arms reduction treaty. Ideally, it could also lead to a statement of support for the goal of eliminating nuclear weapons, as specified in the UN treaty on the prohibition of nuclear weapons.

To build pressure for such steps, renewed peace activism is needed. Change will require political pressure from the bottom up. In the history of the arms race, steps for weapons limitation and disarmament usually have been the result of citizen pressure and grassroots political action. We need more of the same now.

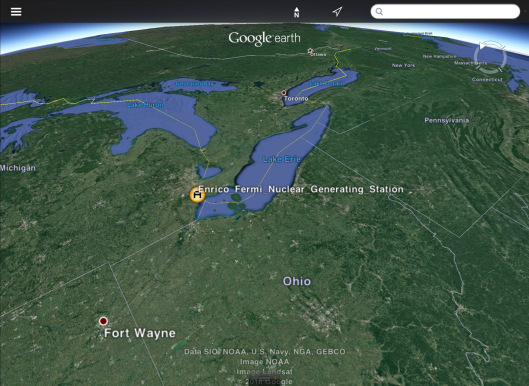

An environmental coalition defends Environmental Justice (EJ) against the Canadian Nuclear Waste Management Organization’s (NWMO) latest Deep Geological Repository (DGR) scheme.

February 5, 2026, https://beyondnuclear.org/enviro-coalition-defends-ej-against-nwmo-dgr/

An environmental coalition — Beyond Nuclear, Coalition for a Nuclear-Free Great Lakes, Don’t Waste Michigan, and Nuclear Information and Resource Service (NIRS) — has defended Environmental Justice (EJ) against the Canadian Nuclear Waste Management Organization’s (NWMO) latest Deep Geological Repository (DGR) scheme.

The coalition submitted extensive comments on NWMO’s Initial Project Description Summary.

NWMO is targeting the Wabigoon Lake Ojibway Nation and the Township of Ignace, in northwestern Ontario, north of Minnesota and a relatively short distance outside of the Great Lakes (Lake Superior) watershed, for permanent disposal of a shocking 44,500 packages of highly radioactive irradiated nuclear fuel.

The Mobile Chornobyls, Floating Fukushimas, Dirty Bombs on Wheels, Three Mile Island in Transit, and Mobile X-ray Machines That Can’t Be Turned Off would travel very long distances, including on routes through the Great Lakes watershed, from Canadian reactors to the south and east, thereby increasing transport risks and impacts.

The watershed at the proposed Revell Lake DGR site flows through Lake of the Woods, Minnesota, sacred to the Ojibwe. Lake of the Woods contains many islands, some adorned with ancient rock art.

Indigenous Nations and organizations, including Fort William First Nation, Nishnawbe Aski Nation, Grassy Narrows First Nation, Neskantaga First Nation, and the Land Defence Alliance rallied against NWMO’s DGR last summer in Thunder Bay, Ontario, on the shore of Lake Superior.

Beyond Nuclear’s radioactive waste specialist, Kevin Kamps, traveled to Thunder Bay last spring, to speak out against NWMO’s DGR at the Earth Day annual meeting of Environment North.

We the Nuclear-Free North organized the public comment effort, greatly aiding our coalition to meet the deadline.

Our coalition groups worked with Canadian and Indigenous allies for two decades to stop another DGR, targeted by Ontario Power Generation (which dominates the NWMO) at the Bruce Nuclear Generating Station in Kincardine, Ontario, on the Lake Huron shore. Bruce is the largest nuclear power plant in the world by number of reactors — nine! The final nail in the Bruce DGR came from the very nearby Saugeen Ojibwe Nation, which voted 86% to 14% against hosting the DGR!

Iran suggests it could dilute highly enriched uranium for sanctions relief

Aljazeera, 9 Feb 26

Iran’s atomic energy chief makes comment as more mediated negotiations with the US expected.

Iran’s atomic energy chief says Tehran is open to diluting its highly enriched uranium if the United States ends sanctions, signalling flexibility on a key demand by the US.

Mohammad Eslami made the comments to reporters on Monday, saying the prospects of Iran diluting its 60-percent-enriched uranium, a threshold close to weapons grade, would hinge on “whether all sanctions would be lifted in return”, according to Iran’s state-run IRNA news agency.

Eslami did not specify whether Iran expected the removal of all sanctions or specifically those imposed by the US.

Diluting uranium means mixing it with blend material to reduce its enrichment level. According to the United Nations nuclear watchdog, Iran is the only state without nuclear weapons enriching uranium to 60 percent.

US President Donald Trump has repeatedly called for Iran to be subject to a total ban on enrichment, a condition unacceptable to Tehran and far less favourable than a now-defunct nuclear agreement reached with world powers in 2015.

Iran maintains it has a right to a civilian nuclear programme under the provisions of the nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, to which it and 190 other countries are signatories.

Eslami made his comments on uranium enrichment as the head of Iran’s Supreme National Security Council, Ali Larijani, prepares to head on Tuesday to Oman, which has been hosting mediated negotiations between the US and Iran.

Al Jazeera’s Ali Hashem, reporting from Tehran, said Larijani, one of the most senior officials in Iran’s government, is likely to convey messages related to the ongoing talks

Trump said talks with Iran would continue this week……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2026/2/9/iran-suggests-it-could-dilute-highly-enriched-uranium-for-sanctions-relief

Why Iran–US negotiations must move beyond a single-issue approach to the nuclear problem

By Seyed Hossein Mousavian | February 5, 2026, https://thebulletin.org/2026/02/why-iran-us-negotiations-must-move-beyond-a-single-issue-approach-to-the-nuclear-problem/?utm_source=ActiveCampaign&utm_medium=email&utm_content=Iran-US%20negotiations&utm_campaign=20260209%20Monday%20Newsletter

Iran’s nuclear crisis has reached a point at which it can no longer be treated as a purely technical or legal dispute within the framework of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT). It has evolved into a deeply security-driven, geopolitical, and structural challenge whose outcome is directly tied to the future of the nonproliferation order in the Middle East and beyond. If the negotiations scheduled for Friday between Iran and the United States are to be effective and durable, they must move beyond single-issue approaches and toward a comprehensive, direct, and phased dialogue.

The format and venue of Iran–US negotiations. The first round of talks between Iranian Foreign Minister Abbas Araghchi and US envoy Steve Witkoff took place on April 12, 2025, in Muscat, Oman. At Iran’s insistence, these negotiations were defined as “indirect.” On April 8, 2025, I emphasized in a tweet that direct negotiations—particularly in Tehran—would significantly increase the chances of reaching a dignified, realistic, and timely agreement. “Wasting time is not in the interest of either country,” I insisted. Despite these warnings, nearly 10 months were lost, during which the region suffered heavy and regrettable losses.

It now appears that Tehran has agreed to direct talks among Witkoff, son-in-law and key adviser to President Trump Jared Kushner, and Araghchi, again in Oman. The most effective format going forward, however, would be to hold direct talks in Tehran and then in Washington. This formula would not only break long-standing political taboos but also enable deeper mutual understanding. A visit by Witkoff and Kushner to Tehran would allow them to engage not only with the foreign minister but also with other key decision-makers, including the secretary of the Supreme National Security Council, members of parliament, and relevant institutions—engagement that is essential if any sustainable agreement is to be achieved. Araghchi should engage in Washington not only with US negotiators, but also with President Trump, officials from the Pentagon, and members of the US Congress, to gain a clearer understanding of the current political environment in Washington.

Why a single-issue agreement is not sustainable. In hundreds of articles and interviews since 2013, I have argued that a single-issue agreement—even if successful on the nuclear file—will be inherently unstable. Under current conditions, three core issues require reasonable, dignified, and lasting solutions.

The US demand for zero enrichment. Ahead of negotiations, the United States is demanding that Iran entirely stop all uranium enrichment and give up its stockpile of around 400-kilograms of highly enriched uranium, steps that would prevent Tehran from possible diversion toward weaponization. Since 2013, a group of prominent nuclear scientists from Princeton University and I have proposed a “joint nuclear and enrichment consortium” for the Persian Gulf and the broader Middle East as a way for Iran to continue its peaceful nuclear program and for the United States and regional countries to be reassured that program will not be used as a cover for the production of nuclear weapons. This proposal was repeatedly articulated—up to 10 days before the 2025 Israeli and US attacks on Iran—but unfortunately failed to gain serious attention.

Today, the only realistic solution to the question of uranium enrichment remains the establishment of a joint nuclear and enrichment consortium involving Iran, Turkey, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, the Arab states of the Persian Gulf, and major global powers. This model would address nuclear proliferation concerns while safeguarding equal access to peaceful nuclear technology.

Iran’s missile and defensive capabilities. Defensive capabilities are the ultimate guarantor of territorial integrity, sovereignty, and national security. Since 2013, I have repeatedly recommended two regional agreements: a conventional weapons treaty and a non-aggression pact among the states in the Persian Gulf and the Middle East. A regional conventional weapons treaty would ensure a balance of defensive power, while a non-aggression pact would lay the foundation for collective security. Without these frameworks, expectations for unilateral limitations on Iran’s defensive capabilities are neither realistic nor sustainable.

Iran’s support for the “axis of resistance” and regional security order. My book, A New Structure for Security, Peace, and Cooperation in the Persian Gulf, presented a comprehensive framework for regional cooperation and collective security, including a nuclear and weapons of mass destruction free zone. This framework would enable progress on four major issues: the roles of non-state and semi-state actors; the Persian Gulf and energy security; the antagonism among Iran, the United States, and Israel; and a safe and orderly US withdrawal from the region.

If a sustainable agreement is to be reached, Iran and Israel must put an end to mutual existential, military, and security threats. “Despite major differences, the United States and China both worry about the conflict. China has close Iran relations, and Israel is a US strategic partner, making them qualified mediators serving as communication channels,” I suggested in 2023.

A warning to Washington: Iran’s nuclear file and the future of nonproliferation. The global non-proliferation order is undergoing a fundamental transition. The world is moving away from a system in which nuclear strategy is defined by possession or non-possession of nuclear weapons, and toward one defined by positioning, reversibility, and strategic optionality.

Nuclear-weapon states have not only failed to meet their NPT obligations to make good-faith efforts toward nuclear disarmament; they are also actively modernizing and expanding their arsenals. At the same time, some non-nuclear states that face threats to their security are seeking deterrence without formal weaponization, and political leverage without legal rupture.

The Iranian case demonstrated that full compliance with the 2015 Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (aka the Iran nuclear deal) and unprecedented cooperation with the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) did not produce security for Iran. The US withdrawal from the agreement, the imposition of sweeping sanctions, and subsequent military attacks conveyed a clear message to the Iranian government: Maximum restraint can create vulnerability. Meanwhile, Israel—outside the NPT and enjoying unwavering US support—remains the region’s sole nuclear-armed state.

For the first time in the history of nuclear non-proliferation, safeguarded nuclear facilities of a non-nuclear-weapon state were attacked, without meaningful condemnation from either the IAEA or the UN Security Council. This episode has fundamentally altered the meaning of non-proliferation commitments.

The conclusion is clear: If Iran’s nuclear crisis is treated as a narrowly defined, Iran-specific issue, it will not lead to a sustainable agreement. Instead, it will accelerate the spread of “nuclear ambiguity” across the Middle East as multiple countries seek the capability to build nuclear weapons, even if they do not immediately construct weapons. Any new nuclear agreement between Iran and the United States must therefore be firmly grounded in the principles and obligations of the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), applied in a balanced, non-discriminatory, and credible manner. The fate of Iran-US negotiations is inseparably linked to the future of non-proliferation in the region and around the world. Decisions made today will shape regional and international security for decades to come.

-

Archives

- February 2026 (105)

- January 2026 (308)

- December 2025 (358)

- November 2025 (359)

- October 2025 (376)

- September 2025 (258)

- August 2025 (319)

- July 2025 (230)

- June 2025 (348)

- May 2025 (261)

- April 2025 (305)

- March 2025 (319)

-

Categories

- 1

- 1 NUCLEAR ISSUES

- business and costs

- climate change

- culture and arts

- ENERGY

- environment

- health

- history

- indigenous issues

- Legal

- marketing of nuclear

- media

- opposition to nuclear

- PERSONAL STORIES

- politics

- politics international

- Religion and ethics

- safety

- secrets,lies and civil liberties

- spinbuster

- technology

- Uranium

- wastes

- weapons and war

- Women

- 2 WORLD

- ACTION

- AFRICA

- Atrocities

- AUSTRALIA

- Christina's notes

- Christina's themes

- culture and arts

- Events

- Fuk 2022

- Fuk 2023

- Fukushima 2017

- Fukushima 2018

- fukushima 2019

- Fukushima 2020

- Fukushima 2021

- general

- global warming

- Humour (God we need it)

- Nuclear

- RARE EARTHS

- Reference

- resources – print

- Resources -audiovicual

- Weekly Newsletter

- World

- World Nuclear

- YouTube

-

RSS

Entries RSS

Comments RSS