Memory as Resistance: Why Hibakusha Testimonies Matter for Nuclear Justice Today

By Monalisa Hazarika

ICAN Australia and Monalisa Hazarika, Dec 19, 2025, https://icanaustralia.substack.com/p/memory-as-resistance-why-hibakusha?utm_source=post-email-title&publication_id=6291617&post_id=181742900&utm_campaign=email-post-title&isFreemail=true&r=1ise1&triedRedirect=true&utm_medium=email

How do we live with memories of discrimination when they are woven into our earliest or most defining experiences? How do we find the strength to speak about encounters we would rather protect our loved ones from? And how do we ensure that the injustices we faced are never repeated? For hibakusha, these questions are not rhetorical; their testimonies turn memory into resistance—insisting that lived experience remains central to struggles for nuclear justice today.

The Story of Lee Jong Keun

The following tells the story of Lee Jong Keun, a non-Japanese hibakusha, as shared by his legacy successor, Mozume Megumi—who has been entrusted to convey his testimony. Mr. Lee, born in 1928, was a Zainichi (residing in Japan) Korean with the Japanese name Egawa Masaichi. He, like many other Koreans at that time, was forced to adopt Japanese-style family names as part of Soshi Kaimei—a Japanese colonial policy aimed at broader assimilation efforts. As a Zainichi, he experienced persistent discrimination from childhood, including being targeted for something as simple as bringing Korean food in his lunchbox. He noted that in school, he was routinely singled out and blamed for wrongdoing, reflecting the broader social prejudice faced by Korean minorities in Japan.

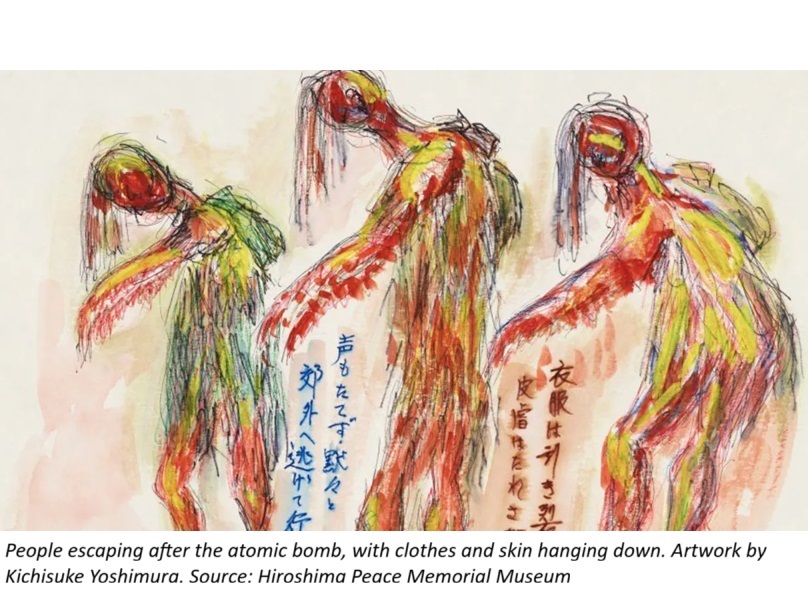

At sixteen, Mr. Lee was a mechanic living in the suburbs of Hiroshima, taking the train each day to his workshop. But on the morning of August 6, 1945, he missed his usual stop and boarded a tram instead—a small change that, as he later said, ended up saving his life. He recalled seeing a sudden pika (a blinding flash), thinking it was a flare bomb, and instinctively covered his eyes, nose, and ears, and crouched on the ground. When he opened his eyes again, the previously sunny morning had turned into pitch-black darkness. People were running for shelter, others trapped under rubble were crying for help. The city was unrecognisable. He described seeing people with peeling skin, charred bodies, and desperate cries for assistance; images that left him feeling helpless, confused, and overwhelmed by fear and pain.

As a railroad worker, he received the limited medical care available, mostly Mercurochrome—a red antiseptic containing mercury—which his family used to treat his burns. He remembered his mother quietly crying as she cleaned the wounds each day, removing maggot eggs and tending to the foul-smelling injuries on his back. Her whispered fear that death might have been kinder than such suffering stayed with him. Yet amid the devastation, he also remembered the kindness of his neighbours. One family, despite having very little themselves, shared a small jar of vegetable oil each week to soothe his burns—an act of generosity that stood in stark contrast to the stigma and isolation survivors faced during that time.

Hibakusha and Non-Japanese Hibakusha

Hibakusha—atomic bomb survivors—faced profound social, economic, and psychological discrimination rooted in widespread misconceptions about radiation sickness. In post-war Japan, many believed that radiation-related conditions were contagious or hereditary, resulting in exclusion from employment, healthcare, marriage prospects, and community life. For non-Japanese hibakusha such as Mr. Lee, this marginalisation was compounded by ethnic discrimination. They endured both the trauma of the bombings and the persistent stigma of being perceived as “outsiders,” leading some, including Mr. Lee, to conceal their survivor status from even close family members for decades. They faced social stigma linked to radiation’s visible effects and persistent institutional neglect tied to their nationality and residency status

Beyond social prejudice, non-Japanese hibakusha have continued to confront bureaucratic obstacles, limited political recognition, and inconsistent access to state support. Restrictions on eligibility for medical subsidies, complex residency verification processes, and legal battles over compensation have left many without adequate care. Their exclusion from formal policymaking spaces has further limited their ability to advocate for their rights. Despite incremental progress, these survivors remain on the margins of disarmament and public health policy, underscoring the need for sustained diplomatic attention, inclusive historical acknowledgment, and equitable survivor support frameworks.

Stories like Mr. Lee’s are not alone and stand as stark reminders of the human cost of misguided policies pursued in the name of national or global security. Across Japan and around the world, thousands of hibakusha, their descendants, and dedicated activists continue to shoulder the burden of history while working tirelessly to ensure its lessons are not forgotten with a collective message: never again!

Hibakusha testimonies are not only records of past violence—they are acts of resistance. By insisting on truth, dignity, and accountability, they challenge systems that normalise nuclear harm and demand justice in the present.

Under Article 6 of the United Nations Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW), states must provide age and gender sensitive assistance to victims of nuclear weapons use or testing. This must be enacted without discrimination, including medical care, rehabilitation, and psychological support, and provide for their social and economic inclusion. Countries must be obligated to assist survivors, many of whom share a similar story to Mr Lee, and ensure that nuclear weapons use and testing are prohibited in the future, possible through the advocacy of the TPNW.

About the Author

Monalisa Hazarika is the Strategic Communication and Partnership Officer at the SCRAP Weapons Project. She is one of the UN Youth Champions for Disarmament under the United Nations Office for Disarmament Affairs’ #Youth4Disarmament programme. She is an emerging voice in conventional arms control and meaningful youth engagement, featuring most recently at a UNGA-ECOSOC Joint Meeting. Her areas of expertise and research focus include small arms and light weapons, especially non-industrial weapons and their trends in illicit manufacture and trade, transnational organised crime, and the proliferation of 3D-printed weapons.

No comments yet.

-

Archives

- February 2026 (95)

- January 2026 (308)

- December 2025 (358)

- November 2025 (359)

- October 2025 (376)

- September 2025 (258)

- August 2025 (319)

- July 2025 (230)

- June 2025 (348)

- May 2025 (261)

- April 2025 (305)

- March 2025 (319)

-

Categories

- 1

- 1 NUCLEAR ISSUES

- business and costs

- climate change

- culture and arts

- ENERGY

- environment

- health

- history

- indigenous issues

- Legal

- marketing of nuclear

- media

- opposition to nuclear

- PERSONAL STORIES

- politics

- politics international

- Religion and ethics

- safety

- secrets,lies and civil liberties

- spinbuster

- technology

- Uranium

- wastes

- weapons and war

- Women

- 2 WORLD

- ACTION

- AFRICA

- Atrocities

- AUSTRALIA

- Christina's notes

- Christina's themes

- culture and arts

- Events

- Fuk 2022

- Fuk 2023

- Fukushima 2017

- Fukushima 2018

- fukushima 2019

- Fukushima 2020

- Fukushima 2021

- general

- global warming

- Humour (God we need it)

- Nuclear

- RARE EARTHS

- Reference

- resources – print

- Resources -audiovicual

- Weekly Newsletter

- World

- World Nuclear

- YouTube

-

RSS

Entries RSS

Comments RSS

Leave a comment