Trump’s new radiation exposure limits could be ‘catastrophic’ for women and girls.

it has since been widely documented that women and young girls are significantly more vulnerable to radiation harm than men—in some cases by as much as a ten-fold difference………… Those most impacted by weaker exposure standards will be young girls under five years old

By Lesley M. M. Blume, Chloe Shrager | November 14, 2025, https://thebulletin.org/2025/11/trumps-new-radiation-exposure-limits-could-be-catastrophic-for-women-and-girls/

In a May executive order, aimed at ushering in what he described as an “American nuclear renaissance,” President Donald Trump declared moot the science underpinning decades-old radiation exposure standards set by the federal government. Executive Order 14300 directed the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) to conduct a “wholesale revision” of half-a-century of guidance and regulations. In doing so, it considers throwing out the foundational model used by the government to determine exposure limits, and investigates the possibility of loosening the standard on what is considered a “safe” level of radiation exposure for the general public. In a statement to the Bulletin, NRC spokesperson Scott Burnell confirmed that the NRC is reconsidering the standards long relied upon to guide exposure limits.

Now, some radiology and policy experts are sounding alarm bells, calling the directive a dangerous departure from a respected framework that has been followed and consistently reinforced by scientific review for generations. They warn that under some circumstances, the effects of the possible new limits could range from “undeniably homicidal” to “catastrophic” for those living close to nuclear operations and beyond.

“It’s an attack on the science and the policy behind radiation protection of people and the environment that has been in place for decades,” says radiologist Kimberly Applegate, a former chair of the radiological protection in medicine committee of the International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP) and a current council and scientific committee member of the National Council on Radiation Protection (NCRP)—two regulatory bodies that make radiation safety recommendations to the NRC. According to Applegate, current government sources have told her and other experts that the most conservative proposed change would raise the current limit on the amount of radiation that a member of the general public can be exposed to by five times. That would be a standard “far out of the international norms,” she says, and could significantly raise cancer rates among those living nearby. The NRC spokesperson did not respond to a question from the Bulletin about specific new exposure limits being considered.

Kathryn Higley, president of the NCRP, warns that a five-fold increase in radiation dose exposure would look like “potentially causing cancers in populations that you might not expect to see within a couple of decades.”

“There are many things that Executive Order does, but one thing that’s really important is that it reduces the amount of public input that will be allowed,” says Diane D’Arrigo, the Radioactive Waste Project Director at the Nuclear Information and Resource Service, a nonprofit group critical of the nuclear energy industry. In a statement to the Bulletin, the NRC said that once its standards reassessment process is completed, the NRC will publish its proposed rules in the Federal Register for public comment.* The NRC spokesperson did not respond to questions about when the proposed new standards would be made public and whether or how the general public would be further alerted to the changes.

Once the proposed policy change hits the Federal Register, the final decision will likely follow in a few days without advertising a period for public input, Applegate adds.

“I’m not sure I know why the loosening is needed,” says Peter Crane, who served as the NRC’s Counsel for Special Projects for nearly 25 years, starting in 1975. “I think it’s ideologically driven.” He points out that the probable loosening of the standards is set to coincide with increased pressure to greenlight new nuclear plants and could weaken emergency preparedness in case of leaks or other accidents: “I think it’s playing with fire.” (The NRC’s Office of Public Affairs did not respond to questions about the rationale for loosening the standards and the timing of the reconsideration.)

Possible shorter timelines for building nuclear power plants, coinciding with weakened radiation exposure standards, could spell disaster, warn other experts. It would be “undeniably homicidal” of the NRC to loosen current US exposure standards even slightly, adds Mary Olson, a biologist who has researched the effects of radiation for over 40 years and published a peer-reviewed study titled “Disproportionate impact of radiation and radiation regulation” in 2019. Olson cites NRC equations that found that the current exposure standards result in 3.5 fatal cancers per 1,000 people exposed for their lifetimes by living near a nuclear facility; a five-fold rate increase in allowable radiation exposure could therefore result in a little over 17.5 cancers per 1,000 people. Expressed another way, that means “one in 57 people getting fatal cancer from year in, year out exposure to an NRC facility,” she says.

The NRC’s Office of Public Affairs did not respond to questions about whether the NRC could guarantee the current level of safety for the general public or nuclear workers if adopting looser radiation exposure standards, and about whether new protections would be put into place.

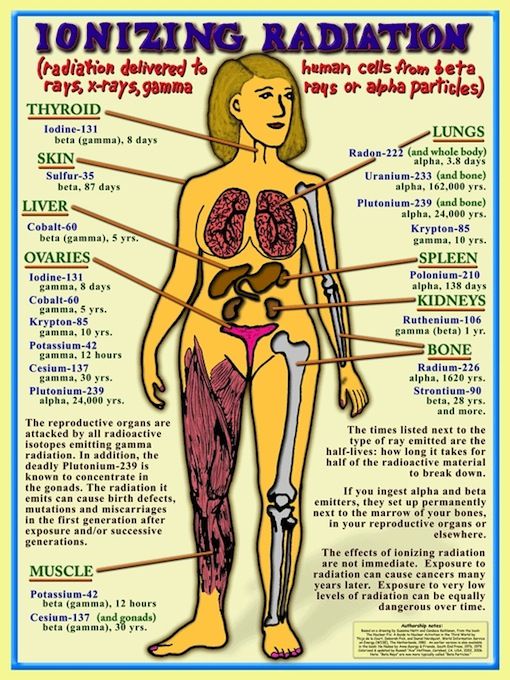

Are women and children more vulnerable? According to Olson, increased radiation exposure could be even more “catastrophic” for women and children. Exposure standards have long been determined by studies on how radiation affects the “reference man,” defined by the ICRP as a white male “between 20-30 years of age, weighing around 70 kilograms [155 pounds].”

But Applegate, Olson, and other experts say that it has since been widely documented that women and young girls are significantly more vulnerable to radiation harm than men—in some cases by as much as a ten-fold difference, according to Olson’s 2019 study. Olson and Applegate cite another 2006 review assessing and summarizing 60 years of health data on the survivors of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki atomic bombings; the study showed that women are one-and-a-half to two times as likely to develop cancer from the same one-time radiation dose as men.

Young girls are seven times more at risk, they say. Those most impacted by weaker exposure standards will be young girls under five years old, Olson says. Her 2024 study of the A-bomb bomb survivor data for the United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research, titled “Gender and Ionizing Radiation,” found that they face twice the risk as boys of the same age, and have four to five times the risk of developing cancer later in life than a woman exposed in adulthood.

“Protections of the public from environmental poisons and dangerous materials have to be focused on those who will be most harmed, not average harmed,” Olson says. “That’s where the protection should be.”

Infants are especially vulnerable to radiation harm, says Rebecca Smith-Bindman, a radiologist and epidemiologist who is the lead author of a just-released major study in the New England Journal of Medicine documenting the relationship between medical imaging (such as X-rays and CT scans) and cancer risk for children and adolescents; more than 3.7 million children born between 1996 and 2016 participated and have been tracked. Smith-Bindman contests the idea that women are overall more vulnerable to cancer than men, saying that “in general, maybe women are a little bit more sensitive, …[but] women and men have different susceptibilities to different cancer types,” with women being more vulnerable to lung and breast cancers, among other types. But it is “absolutely true that children are more susceptible,” she adds. With children under the age of one, “the risks are markedly elevated.” While these findings are sobering, she points out that with medical imaging, “there’s a trade-off…it helps you make diagnoses; it might save your life. It’s very different from nuclear power or other sources of radiation where there’s no benefit to the patient or the population. It’s just a harm.”

“We’ve known for decades that pregnancy is [also] more impacted” by radiation exposure, says Cindy Folkers, radiation and health hazard specialist at Beyond Nuclear, a nonprofit anti-nuclear power and weapons organization. “Radiation does its damage to cells, and so when you have a pregnancy, you have very few cells that will be developing into various parts of the human body: the skeleton, the organs, the brain,” and exposing those cells to radiation during pregnancy can impact the embryo’s health, she says. Smith-Bindman and her team are also studying the impact of radiation exposure on pregnancy, and while their results are not yet in, “we do know that exposures during pregnancy are harmful,” she says, “and that they result in elevated cancer risks in the offspring of those patients.”

For children, lifetime cancer risk will be increased not only because of the “sensitivity and vulnerability of developing tissues, but also partly [because] they would be living longer under a different radiation protection framework,” adds David Richardson, a UC Irvine professor who studies occupational safety hazards.

Several experts noted the irony that these changes are being mandated by the same administration that is also overseeing a policy of “Make America Healthy Again” (MAHA), an effort being spearheaded by Secretary of Health and Human Services Robert F. Kennedy Jr. “In terms of general [public] knowledge, I think there has not been very large coverage or acceptance of the idea that radiation affects different people differently on the basis of both age and biological sex,” says Olson. “But we now have enough reviews, enough literature to say that the biological sex difference is there. I don’t think MAHA mothers know this because it’s been underreported, [and] they would be concerned if they knew it.”

The NRC’s Office of Public Affairs did not respond to questions about concerns being raised by radiologists and epidemiologists about possible health consequences—especially for children—as a result of increased radiation exposure.

Raising the radioactive roof. In the past, restrictions on exposures have only ever been tightened by regulatory authorities. The linear no-threshold (LNT) model—which has underpinned regulations since the late 1950s—called for exposures to be “as low as reasonably achievable,” or the ALARA principle. Regulators have consistently agreed that “they shouldn’t expose people up to the limit,” says Olson.

In 1987, President Ronald Reagan issued presidential guidance to federal agencies calling for “a sustained effort [to] be made to ensure that collective doses, as well as annual, committed and cumulative lifetime individual doses, are maintained as low as reasonably achievable.” This guidance also stated that children under the age of 18 should be limited to one-tenth the dose exposures allowed for adults. It also called for special protections for pregnant workers—guidance which underscores the government’s longtime knowledge of the special vulnerability of expectant mothers.

In 2018, the NCRP reevaluated the LNT model and concluded that it continues to be a “pragmatic approach” to managing risk, Higley says, calling it “good housekeeping.”

“Radiation protection is a combination of science, ethics, and policy. The science can only take you so far,” she says, adding that LNT “threads the needle through all of these different response models.” The new executive order could result in the jettisoning of both LNT and ALARA. In a statement to the Bulletin, NRC spokesperson Burnell confirmed that “in accordance with the mandate of Executive Order 14300, the NRC is reconsidering its reliance on LNT/ALARA as part of its ongoing rulemaking effort.” He did not answer a question about what standards the NRC might rely on instead of the LNT when determining new exposure thresholds.

“That goes against science,” says Allison Macfarlane, director of the School of Public Policy and Global Affairs at the University of British Columbia and chairman of the NRC from 2012 to 2014. “But this administration seems to go against science at every step.” The NRC, she adds, is no longer functioning as an independent regulatory authority: “The public should not be reassured that they are safe.” The current standard remains today that members of the general American public can be exposed to a “safe” level of 100 millirems of radiation annually—the equivalent of 10 chest X-rays. In a July report commissioned by the Energy Department, Idaho National Laboratory recommended to the NRC and other relevant federal agencies that the public exposure standard be raised to 500 millirems. (The Roentgen equivalent man [rem] is a unit of effective absorbed radiation in human tissue, equivalent to one roentgen of X-rays.) The Lab report also suggests a future tenfold increase in exposure limits for nuclear workers.

The current protections already allow for significant risks, says nuclear engineer David Lochbaum, former director of the Nuclear Safety Project for the Union of Concerned Scientists and author of a March 2024 report on radiation exposure harm generated by the US nuclear weapons program over the past eight decades. “A Congressional study [shows] that 98 percent of the compensation to [sickened civilians] was for radiation exposure LESS than the allowable level,” he said in an email.

Despite the risks involved with the current public exposure standard, “I would rather keep it, because where they’re going with this executive order is going to be much worse,” says Cindy Folkers of Beyond Nuclear. The new change is unnecessary, adds NCRP’s Higley, who voiced her support for adherence to the current standards at an open NRC meeting this past July.

“Arbitrarily increasing the exposure of the population, what is the benefit that’s being gained by those individuals for this increased risk that they’re going to be bearing?” she asks. “That’s the question.”

Potential impacts to already-reeling Superfund sites. Experts warn that there are vast additional implications of the executive order, including relaxation of cleaning and containment standards at reactors and other nuclear operations. The reduced standards, they say, could allow nuclear facility operators to follow more inadequate or negligent procedures for the maintenance of radioactive waste at decommissioned reactors and contaminated Superfund sites. (These sites include former manufacturing facilities, processing plants, landfills, and mining sites contaminated by radioactivity and whose environmental clean-up is covered by the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation and Liability Act (CERCLA) of 1980, informally called Superfund.) Looser standards could possibly even permit site operators to abandon altogether clean-up efforts at contaminated sites in residential areas.

“If you get rid of ALARA, people are going to get sloppy,” Applegate says.

Sites such as Coldwater Creek—a contaminated Superfund site that sprawls through urban and residential St. Louis, Missouri—could immediately be impacted by this new policy. During the World War II-era Manhattan Project, nuclear waste from a former uranium enrichment plant was improperly disposed of at the local airport and a nearby landfill, leaching radioactive material into the river running through neighborhoods. Coldwater Creek has yet to be properly cleaned, and the health impacts have been widely and acutely felt in the area.

Experts warn that women and children around such sites have already been shown to be particularly vulnerable to health fallout. Cancer rates among women and girls around Coldwater Creek are already “astronomical,” and survival rates are low, says Dawn Chapman, one of the co-founders of Just Moms STL, a nonprofit that advocates for the cleanup of her community, and a leader of the initiative to reinstate and expand the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act to cover affected areas of St. Louis.

“These female cancers and these exposures are not just rare cancers,” Chapman says. “It’s not just that they’re happening younger, with no genetic predisposition, but they’re very aggressive and they’re almost immune to the typical types of chemotherapy and cancer treatments.” For example, she’s seen 16-year-old girls without the BRCA gene get breast cancer. (According to the National Cancer Institute, the BRCA1 [BReast CAncer gene 1] and BRCA2 [BReast CAncer gene 2] are inherited genes that may mutate, prompting a possible “increased risks of several cancers—most notably breast and ovarian cancer.”)

Just last month, the St. Louis Public Health Department alerted residents of Coldwater Creek that they were 18 percent more likely to be diagnosed with cancer than the national average, and that the burden of breast cancer is “especially concerning.” Chapman said the data regarding cancer rates “shocked the shit out of us,” and says that she fears that further loosening the radiation exposure safety threshold would not only threaten proper protections at Coldwater Creek, she said, but also allow “more Coldwater Creeks to form.”

“My big concern is that decommissionings won’t happen, cleanups won’t happen,” Olson says. “They’ll be turned into commercially purchasable places, reusable places.” She adds that for as long as the expected looser standards are in place, “there will be radioactivity dispersing into our environment, and a lot of it will persist for years, decades, and centuries. There’s no easy way to get it back once it’s out there. It will affect not only us, but our children, our grandchildren, and many generations to come.”

The NRC’s Office of Public Affairs did not respond to a Bulletin question about whether abandonment of the LNT might allow for the deregulation of certain levels of radioactive waste and potentially impact clean-up efforts at Superfund sites.

Nuclear waste today; consumer products tomorrow? Experts also warn that looser exposure standards might also lead to radioactive materials below a certain level being recycled into consumer products with no labeling or disclosures—effectively reviving a “below regulatory concern” policy revoked by the NRC in 1993 that deregulated low-level radioactive waste. A comparable “very low-level waste” policy was proposed in 2020 and rejected by the NRC. With weaker standards in place, some experts say, government agencies or entities that work with radioactive materials could sell materials that still emit radioactivity, albeit below the threshold newly dictated by the NRC: “There are salvage companies that they sell to. There are some [materials] that are sold at auction. There are some things that will be simply put out into regular trash instead of restricted trash,” Olson fears. If the threshold is loose enough, worries D’Arrigo, the recycling practice may become “so pervasive that it’s not going to be stoppable.”

In their 2007 report “Out of Control – On Purpose: DOE’s Dispersal of Radioactive Waste into Landfills and Consumer Products,” D’Arrigo and Olson provided a detailed timeline tracing Energy Department and NRC policies—and specific cases—of deregulated or mishandled radioactive waste entering commercial landfills, recycling streams, and consumer markets since the 1960s. The report narrows in on the case of Tennessee: The state licenses private companies to import, process, and “free release” nuclear waste from across the country, and is, the authors say, the nation’s de facto hub for deregulated radioactive waste disposal and recycling.

According to the report, contaminated materials in this state can be sent to ordinary landfills, combined with chemicals at hazardous waste disposal sites, or recycled into consumer markets with minimal public oversight or recordkeeping. Tennessee is an example of how even now, though it is illegal, “nuclear materials have gotten out into the marketplace by accident,” says D’Arrigo.

“We can easily say that deregulating nuclear waste is going to release [more] manmade radioactive materials … into the marketplace, into everyday household items that we consume, that we use every day,” she says. This could present significant health risks, she adds, especially when those materials are repurposed into products designed for populations most vulnerable to radiation harm: “Our frying pans, our IUDs [intrauterine devices used to prevent pregnancy], our belt buckles, our baby toys… It could be plastics. It could be concrete. It could be asphalt. It could be playgrounds. There’s no limit when you send it out into the marketplace unregulated.”

Olson posits additional alarming recycling scenarios, including uranium enrichment site pipes that carried radioactive waste being reused as scrap metal for cars or silverware, and contaminated nickel from NRC sites in Ohio, Kentucky, and Tennessee being used in rechargeable batteries, which can be subject to overheating and the associated risk of fire and explosion.

“Would everyone have laptops with radioactive batteries sitting on their laps?” she asks. Such material could be released into the international marketplace as well, or originate abroad and be legally imported and sold in the United States. Higley of the NCRP cites an example of radioactive material being melted down with other metals to make window panes in Taiwan in 1999—some of which were incorporated in kindergarten classrooms and exposed children to whole-body gamma radiation—and also cites a recent recall of imported shrimp from an Indonesian food company that the Food and Drug Administration said was contaminated with radioactive cesium. She also recalls an incident at Los Alamos National Laboratory in 1984 when Mexican-manufactured rebar table bases containing radioactive cobalt 60 set off the Lab’s road radiation detectors when driven through the monitors by a steel delivery truck.

The NRC’s Office of Public Affairs did not respond to a comment request from the Bulletin about expert concerns that loosened radiation exposure standards might allow contaminated materials to enter consumer markets; nor did NRC representatives respond to questions about enforcement protocol when it comes to maintaining safe radioactivity levels in materials being considered for reuse.

Despite the risks, Higley says that there is a valuable conversation to be had about sustainability and recycling reusable materials safely within the nuclear industry. But she concedes that the public is reliant on “good actors and a strong regulator” to properly clean contamination from recyclable materials and maintain the safety of consumer goods. With the Trump administration loosening NRC regulations, some experts and industry observers wonder if consumers will be at the mercy of self-regulating consumer products companies.

“We know that there is no zero risk when you’re exposed to radiation, that there could always be something that goes wrong, even [with] the smallest amounts of exposure,” says Beyond Nuclear’s Cindy Folkers. “One of the things that has struck me about this whole deal with the standards is: who’s minding the store? How are the folks that are supposed to be the regulators actually measuring how much is being released from any of these facilities, including nuclear power facilities or uranium mines, or whatever?”

“And really what they’re doing,” she adds, “is shifting the cost of having to containerize this radioactive material from themselves to us—at the cost of our health.”

No comments yet.

-

Archives

- March 2026 (129)

- February 2026 (268)

- January 2026 (308)

- December 2025 (358)

- November 2025 (359)

- October 2025 (376)

- September 2025 (258)

- August 2025 (319)

- July 2025 (230)

- June 2025 (348)

- May 2025 (261)

- April 2025 (305)

-

Categories

- 1

- 1 NUCLEAR ISSUES

- business and costs

- climate change

- culture and arts

- ENERGY

- environment

- health

- history

- indigenous issues

- Legal

- marketing of nuclear

- media

- opposition to nuclear

- PERSONAL STORIES

- politics

- politics international

- Religion and ethics

- safety

- secrets,lies and civil liberties

- spinbuster

- technology

- Uranium

- wastes

- weapons and war

- Women

- 2 WORLD

- ACTION

- AFRICA

- Atrocities

- AUSTRALIA

- Christina's notes

- Christina's themes

- culture and arts

- Events

- Fuk 2022

- Fuk 2023

- Fukushima 2017

- Fukushima 2018

- fukushima 2019

- Fukushima 2020

- Fukushima 2021

- general

- global warming

- Humour (God we need it)

- Nuclear

- RARE EARTHS

- Reference

- resources – print

- Resources -audiovicual

- Weekly Newsletter

- World

- World Nuclear

- YouTube

-

RSS

Entries RSS

Comments RSS

Leave a comment