Calls to restart nuclear weapons tests stir dismay and debate among scientists

Testing “has tremendous symbolic importance,” says Frank von Hippel, a physicist at Princeton University. “During the Cold War, when we were shooting these things off all the time, it was like war drums: ‘We have nuclear weapons and they work. Better watch out.’ ” The cessation of testing, he says, was an acknowledgment that “these [weapons] are so unusable that we don’t even test them.”

A U.S. return to underground detonations would have wide-ranging implications.

Science News, By Emily Conover, March 27, 2025

hen the countdown hit zero on September 23, 1992, the desert surface puffed up into the air, as if a giant balloon had inflated it from below.

It wasn’t a balloon. Scientists had exploded a nuclear device hundreds of meters below the Nevada desert, equivalent to thousands of tons of TNT. The ensuing fireball reached pressures and temperatures well beyond those in Earth’s core. Within milliseconds of the detonation, shock waves rammed outward. The rock melted, vaporized and fractured, leaving behind a cavity oozing with liquid radioactive rock that puddled on the cavity’s floor.

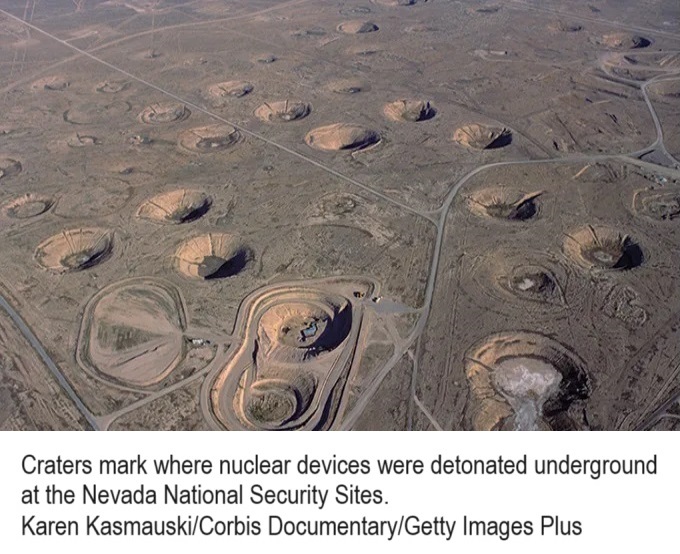

As the temperature and pressure abated, rocks collapsed into the cavity. The desert surface slumped, forming a subsidence crater about 3 meters deep and wider than the length of a football field. Unknown to the scientists.

working on this test, named Divider, it would be the end of the line. Soon after, the United States halted nuclear testing.

Beginning with the first explosive test, known as Trinity, in 1945, more than 2,000 atomic blasts have rattled the globe. Today, that nuclear din has been largely silenced, thanks to the norms set by the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty, or CTBT, negotiated in the mid-1990s.

Only one nation — North Korea — has conducted a nuclear test this century. But researchers and policy makers are increasingly grappling with the possibility that the fragile quiet will soon be shattered.

Some in the United States have called for resuming testing, including a former national security adviser to President Donald Trump. Officials in the previous Trump administration considered testing, according to a 2020 Washington Post article. And there may be temptation in coming years. The United States is in the midst of a sweeping, decades-long overhaul of its aging nuclear arsenal. Tests could confirm that old weapons still work, check that updated weapons perform as expected or help develop new types of weapons.

Meanwhile, the two major nuclear powers, the United States and Russia, remain ready to obliterate one another at a moment’s notice. If tensions escalate, a test could serve as a signal of willingness to use the weapons.

Testing “has tremendous symbolic importance,” says Frank von Hippel, a physicist at Princeton University. “During the Cold War, when we were shooting these things off all the time, it was like war drums: ‘We have nuclear weapons and they work. Better watch out.’ ” The cessation of testing, he says, was an acknowledgment that “these [weapons] are so unusable that we don’t even test them.”……………………………………………………………………………………………………………

“A single United States test could trigger a global chain reaction,” says geologist Sulgiye Park of the Union of Concerned Scientists, a nonprofit advocacy group. Other nuclear powers would likely follow by setting off their own test blasts. Countries without nuclear weapons might be spurred to develop and test them. One test could kick off a free-for-all.

“It’s like striking a match in a roomful of dynamite,” Park says.

The rising nuclear threat

The logic behind nuclear weapons involves mental gymnastics. The weapons can annihilate entire cities with one strike, yet their existence is touted as a force for peace. The thinking is that nuclear weapons act as a deterrent — other countries will resist using a nuclear weapon, or making any major attack, in fear of retaliation. The idea is so embedded in U.S. military circles that a type of intercontinental ballistic missile developed during the Cold War was dubbed Peacekeeper…………………………………………………

….. . The last remaining arms-control treaty between the United States and Russia, New START, is set to expire in 2026, giving the countries free rein on numbers of deployed weapons………………………………………………………………………………..

The United States regularly considers the possibility of testing nuclear weapons……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

Is there a need to test nuclear weapons?

Subcritical experiments are focused in particular on the quandary over how plutonium ages. Since 1989, the United States hasn’t fabricated significant numbers of plutonium pits. That means the pits in the U.S. arsenal are decades old, raising questions about whether weapons will still work.

An aging pit, some scientists worry, might cause the multistep process in a nuclear warhead to fizzle. For example, if the implosion in the first stage doesn’t proceed properly, the second stage might not go off at all.

Plutonium ages not only from the outside in — akin to rusting iron — but also from the inside out, says Siegfried Hecker, who was director of Los Alamos from 1986 to 1997. “It’s constantly bombarding itself by radioactive decay. And that destroys the metallic lattice, the crystal structure of plutonium.”

The decay leaves behind a helium nucleus, which over time may result in tiny bubbles of helium throughout the lattice of plutonium atoms. Each decay also produces a uranium atom that zings through the material and “beats the daylights out of the lattice,” Hecker says. “We don’t quite know how much the damage is … and how that damaged material will behave under the shock and temperature conditions of a nuclear weapon. That’s the tricky part.”

One way to circumvent this issue is to produce new pits. A major effort under way will ramp up production. In 2024, the NNSA “diamond stamped” the first of these pits, meaning that the pit was certified for use in a weapon. The aim is for the United States to make 80 pits per year by 2030. But questions remain about new plutonium pits as well, Hecker says, as they rely on an updated manufacturing process………………………

the benefits of performing a test would be outweighed by the big drawback: Other countries would likely return to testing. And those countries would have more to learn than the United States. China, for instance, has performed only 45 tests, while the United States has performed over 1,000. “We have to find other ways that we can reassure ourselves,” Hecker says…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

Underground tests are not risk-free

Tests that clearly break the rules, however, can be swiftly detected. The CTBT monitoring system can spot underground explosions as small as 0.1 kilotons, less than a hundredth that of the bomb dropped on Hiroshima. That includes the most recent nuclear explosive test, performed by North Korea in 2017.

Despite being invisible, underground nuclear explosive tests have an impact. While an underground test is generally much safer than an open-air nuclear test, “it’s not not risky,” Park says……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………

Even if the initial containment is successful, radioactive materials could travel via groundwater. Although tests are designed to avoid groundwater, scientists have detected traces of plutonium in groundwater from the Nevada site. The plutonium traveled a little more than a kilometer in 30 years. “To a lot of people, that’s not very far,” Park says. But “from a geology time scale, that’s really fast.” Although not at a level where it would cause health effects, the plutonium had been expected to stay put.

The craters left in the Nevada desert are a mark of each test’s impact on structures deep below the surface. “There was a time when detonating either above ground or underground in the desert seemed like — well, that’s just wasteland,” Jeanloz says. “Many would view it very differently now, and say, ‘No, these are very fragile ecosystems, so perturbing the water table, putting radioactive debris, has serious consequences.’ ”…………………………………..

more https://www.sciencenews.org/article/nuclear-weapons-tests-comeback-threats

No comments yet.

-

Archives

- February 2026 (199)

- January 2026 (308)

- December 2025 (358)

- November 2025 (359)

- October 2025 (376)

- September 2025 (258)

- August 2025 (319)

- July 2025 (230)

- June 2025 (348)

- May 2025 (261)

- April 2025 (305)

- March 2025 (319)

-

Categories

- 1

- 1 NUCLEAR ISSUES

- business and costs

- climate change

- culture and arts

- ENERGY

- environment

- health

- history

- indigenous issues

- Legal

- marketing of nuclear

- media

- opposition to nuclear

- PERSONAL STORIES

- politics

- politics international

- Religion and ethics

- safety

- secrets,lies and civil liberties

- spinbuster

- technology

- Uranium

- wastes

- weapons and war

- Women

- 2 WORLD

- ACTION

- AFRICA

- Atrocities

- AUSTRALIA

- Christina's notes

- Christina's themes

- culture and arts

- Events

- Fuk 2022

- Fuk 2023

- Fukushima 2017

- Fukushima 2018

- fukushima 2019

- Fukushima 2020

- Fukushima 2021

- general

- global warming

- Humour (God we need it)

- Nuclear

- RARE EARTHS

- Reference

- resources – print

- Resources -audiovicual

- Weekly Newsletter

- World

- World Nuclear

- YouTube

-

RSS

Entries RSS

Comments RSS

Leave a comment