Becoming a responsible ancestor – about America’s nuclear wastes.

This country, with the world’s largest inventory of high-activity radioactive waste, has not fashioned even a shadow of a strategy for the material’s permanent disposition.

in any case, the burdens would fall on future generations.

Bulletin, By Daniel Metlay | January 13, 2025

After more than four decades of intense struggle, the United States found itself in an unenviable and awkward position by 2015: It no longer had even the barest blueprint of how to dispose of its growing inventory of high-activity radioactive waste.[1] Under the leadership of Rodney Ewing, former chairman of the Nuclear Waste Technical Review Board, and Allison MacFarlane, former chairman of the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, a steering committee composed of a dozen specialists set out to prepare the so-called “reset” report on how to reconstruct that enterprise.[2] In the study’s words: “Reset is an effort to untangle the technical, administrative, and public concerns in such a way that important issues can be identified, understood, and addressed (Steering Committee 2018, 2).”

One of its key recommendations was that a non-profit, single-purpose organization should be established by the owners of the country’s nuclear powerplants to replace the Department of Energy as the implementor of a fresh waste-disposal undertaking.[3]

To appreciate these suggestions, one must first understand how the United States found itself in its current predicament.

How did the United States get here

The roots of the United States’ waste-disposition program can be found in a study prepared by a panel working under the auspices of the National Academy of Sciences (National Research Council 1957). The group’s principal advice was that high-activity waste should be entombed in conventionally mined, deep-geologic repositories such as salt mines.

Early attempts to find a site for the facility met with unanticipated technical difficulties and unflinching opposition from state officials (Carter 1989). President Jimmy Carter appointed an Interagency Review Group to suggest a pathway to unsnarl the Gordian Knot (IRG 1978). Among other things, it counseled the president that a new waste-management program should be established within the Department of Energy. It should investigate multiple potential locations in a variety of geologic formations and choose the one bearing the soundest technical characteristics for development of a repository.

President Ronald Reagan signed the Nuclear Waste Policy Act in January, 1983 (NWPA 1982). The legislation captured the consensus that had emerged around the lion’s share of the Interagency Review Group’s ideas. In particular, the law contained four strategic bargains that were requisite to its passage:

Two repositories would be built, the first in the west and a second in the east, to ensure geographic equity and geologic diversity.- Site-selection would be a technically driven process in which several different hydrogeologic formations would be evaluated against pre-established guidelines.

- States would be given a substantial voice in the choice of sites.

- Upon payment of a fee, the Department of Energy would contract with the owners of nuclear powerplants to accept their waste for disposal starting in January 1998.

By the time Congress enacted the Nuclear Waste Policy Amendments Act a mere five years later, all the bargains had been breached in one way or another (NWPAA 1987; Colglazier and Langum 1988).

Derisively labeled the “Screw Nevada” bill, the new law confined site-selection to Yucca Mountain, located both on and adjacent to the weapons-testing area. Hardly surprisingly, the state mounted an implacable and sustained challenge to the actions of the Department of Energy, including investigations to evaluate the technical suitability of Yucca Mountain and opposition to the license application that the department submitted to the Nuclear Regulatory Commission (Adams 2010).

…………………………………………………………………………………… President Obama directed the new secretary of the Energy Department, Steven Chu, to empanel the Blue Ribbon Commission on America’s Nuclear Future (BRC 2012). Ostensibly not a “siting commission,” it nonetheless proposed a “consent-based” process that was dramatically at odds with the method used to choose the Yucca Mountain site. In addition, the new leadership sought, unsuccessfully as it turns out, to withdraw the license application before the Nuclear Regulatory Commission. Ultimately, funding for the project ran out even during President Donald Trump’s administration, and the Yucca Mountain Project faded into history.

Left in its wake is the current state of affairs. This country, with the world’s largest inventory of high-activity radioactive waste, has not fashioned even a shadow of a strategy for the material’s permanent disposition.

The Department of Energy detailed the consequences of the absence of a policy with its analysis of the No-Action Alternative in the Environmental Impact Statement for Yucca Mountain (DOE 2002, S-79).[4] Under this scenario, the adverse outcomes are seemingly modest—but the calculations exclude effects due to human intrusion as well as sabotage, precisely the rationales for the disposal imperative.

At best, the nation has been left with the regulator’s vague assurance that the owners of the waste can safely extend its storage on the surface for roughly 100 years (NRC 2014). This abdication of accountability—kicking the burden down the road—transforms our generation into irresponsible ancestors.

Why has the United States gotten there

Many independent and reinforcing factors have led to this nation’s precarious moral circumstances. Five of them are worthy of note.

First, striking a balance between protecting the national interest in the disposition of the waste versus state and local interest in warding off a possible calculated risk has proven to be a constant struggle. The Interagency Review Group proposed the nebulous notion of “consultation and concurrence” to suggest that a host state must provide its consent before the repository-development process could proceed to the next step.

Congress morphed that idea into the much weaker “consultation and cooperation” when it passed the Nuclear Waste Policy Amendments Act. But it did authorize the host-state to raise an objection to the president’s selection of the site. That dissent could, however, be overridden by a majority vote in each chamber. As the Yucca Mountain case illustrated, once intensive investigations at a proposed repository location gained momentum and the prospect of restarting site selection lurked in the future, sustaining a protest was only an abstract possibility.

Second, the regulatory regime for approving a repository system was plagued by controversy. In the mid-1980s, the Environmental Protection Agency promulgated radionuclide release standards, and the Nuclear Regulatory Commission issued licensing rules for a generic repository. Directed by Congress in 1992, both agencies later released Yucca Mountain-specific regulations. These protocols proved to be methodologically contested and subject to criticism for changing the “rules of the game.”

Third, the Department of Energy has failed to merit public trust and confidence. A survey conducted by the Secretary of Energy Advisory Board at the height of the Yucca Mountain controversy conclusively demonstrated this reality: None of the interested and affected parties believe that the Department of Energy is very trustworthy. See Figure 1.[on original]

Nor did that deficit of trust and confidence shrink in the coming years. The Blue Ribbon Commission’s and Reset reports underscored this endemic problem. The Department of Energy’s recent initiative to craft a consent-based procedure for siting a federal consolidated interim storage facility positioned restoring public trust at the core of its activities.

Fourth, the Department of Energy’s execution of a stepwise approach to constructing a disposal facility was practically and conceptually flawed. Its license application composed a narrative about how it would meet the Nuclear Regulatory Commission’s regulation mandating that the material be able to be retrieved from an open repository once it was emplaced. That account did not detail the conditions under which the waste might be removed; it did not suggest where it might go; nor did it indicate what might be done if the repository proved to be unworkable. Like extended storage, retrievability of the waste would somehow take place if and when necessary. But, in any case, the burdens would fall on future generations.

Fifth, the Department of Energy encountered difficulties persuasively resolving technical uncertainties. Its license application rested on the premise that the corrosion-resistant Alloy-22 waste packages and the titanium alloy drip shields, which might divert water from the packages, would function to limit the release of radionuclides into the environment. Whether those engineered structures would perform as anticipated in a hot and humid repository may still be an open question. ………………………………….

What should be done

It would be unfair to reproach the Department of Energy alone for all the difficulties that the US waste-disposition program has confronted over the years; sometimes it just was dealt a poor hand by others. Nonetheless, in this writer’s view, reviving that effort demands, among other transformations, a modification in the organization that will execute it in the future.

Indeed, institutional design in the United States is hardly a novel concern. Included in the Nuclear Waste Policy Act was a provision directing the secretary of the Department of Energy to “undertake a study with respect to alternative approaches to managing the construction and operation of all civilian radioactive waste management facilities, including the feasibility of establishing a private corporation for such purposes (NWPA 1992).” That analysis advocated a Tennessee Valley Authority-like corporation, which was labeled “FEDCORP,” to take on the responsibility of constructing and operating a repository (AMFM 1995).

The Blue Ribbon Commission also concluded that:

A new [single-purpose] organization will be in a better position to develop a strong culture of safety, transparency, consultation, and collaboration. And by signaling a clear break with the often troubled history of the U.S. waste management program it can begin repairing the legacy of distrust left by decades of missed deadlines and failed commitments (BRC 2012, 61).

It, too, advised that a FEDCORP should replace the Department of Energy.

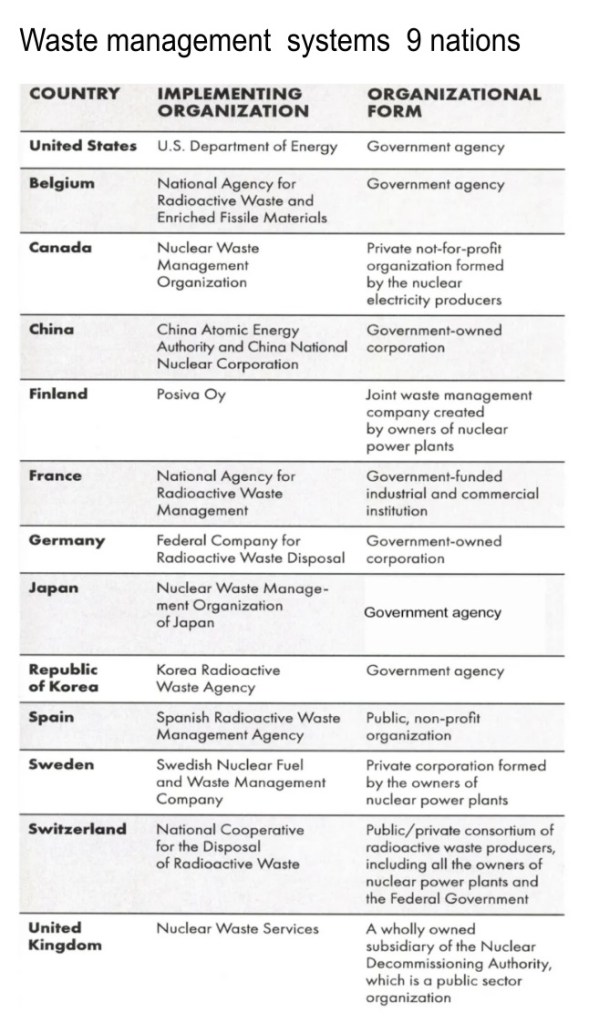

An examination of national waste-disposal undertakings indicates that countries do have several options for structuring their missions. See Figure 2 below [on original].

That multiplicity of alternatives led the majority of the Reset Steering Committee, after intense discussion and consideration, to decide that a more radical approach ought to be adopted. As the group observed: “The track record of nuclear utility-owned implementors abroad…makes at least a prima facie case for considering the creation of a not-for-profit, nuclear utility-owned implementing organization (NUCO) (Steering Committee 2018, 35).”

Of the four nations relying on nuclear utility-owned implementing organizations, three—including Finland, Sweden, and Switzerland—have selected repository sites, and another, Canada, may be on the cusp of doing so. In pointed contrast, only one of the nine countries employing other organizational designs have launched a determined set of site investigations, let along definitely and unequivocally chosen a location to build a repository.

Removing disposal authority from the Department of Energy and passing it on to a nuclear utility-owned implementing organization also permits the full integration of the nuclear fuel cycle. With the exception of disposition, every element is the responsibility of some industrial firm: uranium exploration and conversion, fuel manufacture and configuration, enrichment, reactor design and construction, spent fuel reprocessing (if permitted by law or regulation and if deemed economical), and temporary storage of spent fuel on and off reactor sites.

……………………………………………By creating a nuclear utility-owned implementing organizations, reactor owners can more easily negotiate adjustments with their industrial partners.

But transitioning from the Department of Energy to a nuclear utility-owned implementing organization is unlikely to be a frictionless process. Policymakers in government and industry will have to resolve many particulars. For instance, of central importance is the question of who should pay for the reconstructed program. Since the Nuclear Waste Policy Act’s passage four decades ago, utilities have paid a fee of $0.001 (one mil) per kilowatt of electricity produced. In addition, Congress has periodically appropriated funds to dispose of weapons-origin high-activity waste. Those resources have all been deposited in the Nuclear Waste Fund with the expectation they would pay the full life-cycle costs of the disposition effort.

At the end of Fiscal Year 2024, the Nuclear Waste Fund balance was $52.2 billion dollars (DOE 2024).[5] f a nuclear utility-owned implementing organization were established, one possibility would be to transfer the body of the fund to the new organization. However, the nuclear utility-owned implementing organization might be limited to spending for disposition only the amount of interest that the waste fund generates. In Fiscal Year 2024, that amount was roughly $1.9 billion a year. Notably that income was approximately four times what the Department of Energy spent during the last full year of the Yucca Mountain Project (Consolidated Appropriations Act 2008). Consequently, the new implementor should have sufficient resources to sustain a robust effort. (Under this approach, nuclear utilities would continue to be responsible for storing their spent fuel.)

Another question that would have to be determined is the fate of weapons-origin high-activity radioactive waste. Conceivably the Federal Government might resurrect its own repository effort, perhaps at Yucca Mountain or through a contemporary siting project. Alternatively, the most cost-effective option might be to pay the nuclear utility-owned implementing organizations a disposition fee through congressional appropriations.

Finally, given the weight to its additional responsibilities, the nuclear utility-owned implementing organization must demonstrate that it will be a trustworthy implementor……………………………………………………………….

But for this arrangement to be most effective, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission itself must be viewed more widely as trustworthy…………………………………………………………………………………

Other reforms beyond switching the implementor will urgently be necessary, such as improving the technical credibility of studies to determine the suitability of a potential repository site and structuring a sound step-by-step developmental process. Without the full slate of improvements, this generation will be stuck in the role of irresponsible ancestors. So, the reader should consider this essay as a broader call to action, if only for our children and grandchildren’s sake. https://thebulletin.org/premium/2025-01/becoming-a-responsible-ancestor/?utm_source=ActiveCampaign&utm_medium=email&utm_content=Radioactive%20fallout%20in%20Tokyo%20after%20Fukushima&utm_campaign=20250113%20Monday%20Newsletter

No comments yet.

-

Archives

- February 2026 (115)

- January 2026 (308)

- December 2025 (358)

- November 2025 (359)

- October 2025 (376)

- September 2025 (258)

- August 2025 (319)

- July 2025 (230)

- June 2025 (348)

- May 2025 (261)

- April 2025 (305)

- March 2025 (319)

-

Categories

- 1

- 1 NUCLEAR ISSUES

- business and costs

- climate change

- culture and arts

- ENERGY

- environment

- health

- history

- indigenous issues

- Legal

- marketing of nuclear

- media

- opposition to nuclear

- PERSONAL STORIES

- politics

- politics international

- Religion and ethics

- safety

- secrets,lies and civil liberties

- spinbuster

- technology

- Uranium

- wastes

- weapons and war

- Women

- 2 WORLD

- ACTION

- AFRICA

- Atrocities

- AUSTRALIA

- Christina's notes

- Christina's themes

- culture and arts

- Events

- Fuk 2022

- Fuk 2023

- Fukushima 2017

- Fukushima 2018

- fukushima 2019

- Fukushima 2020

- Fukushima 2021

- general

- global warming

- Humour (God we need it)

- Nuclear

- RARE EARTHS

- Reference

- resources – print

- Resources -audiovicual

- Weekly Newsletter

- World

- World Nuclear

- YouTube

-

RSS

Entries RSS

Comments RSS

Leave a comment