Environmental impacts of underground nuclear weapons testing

While underground nuclear tests were chosen to limit atmospheric radioactive fallout, each test still caused dynamic and complex responses within crustal formations. Mechanical effects of underground nuclear tests span from the prompt post-detonation responses to the enduring impacts resulting in radionuclide release, dispersion, and migration through the geosphere. Every test of nuclear weapons adds to a global burden of released radioactivity (Ewing 1999).

Bulletin, By Sulgiye Park, Rodney C. Ewing, March 7, 2024

Since Trinity—the first atomic bomb test on the morning of July 16, 1945, near Alamogordo, New Mexico—the nuclear-armed states have conducted 2,056 nuclear tests (Kimball 2023). The United States led the way with 1,030 nuclear tests, or almost half of the total, between 1945 and 1992. Second is the former Soviet Union, with 715 tests between 1949 and 1990, and then France, with 210 tests between 1960 and 1996. Globally, nuclear tests culminated in a cumulative yield of over 500 megatons, which is equivalent to 500 million tons of TNT (Pravalie 2014). This surpasses by over 30,000 times the yield of the first atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima on August 6, 1945.

Atmospheric nuclear tests prevailed until the early 1960s, with bombs tested by various means: aircraft drops, rocket launches, suspension from balloons, and detonation atop towers above ground. Between 1945 and 1963, the Soviet Union conducted 219 atmospheric tests, followed by the United States (215), the United Kingdom (21), and France (3) (Kimball 2023).

In the early days of the nuclear age, little was known about the impacts of radioactive “fallout —the residual and activated radioactive material that falls to the ground after a nuclear explosion. The impacts became clearer in the 1950s, when the Kodak chemical company detected radioactive contamination on their film, which was linked to radiation resulting from the atmospheric nuclear tests (Sato et al. 2022). American scientists, like Barry Commoner, also discovered the presence of strontium 90 in children’s teeth originating from nuclear fallout thousands of kilometers from the original test site (Commoner 1959; Commoner 1958; Reiss 1961). These discoveries alerted scientists and the public to the consequences of radioactive fallout from underwater and atmospheric nuclear tests, particularly tests of powerful thermonuclear weapons that had single event yields of one megaton or greater.

Public concerns for the effects of radioactive contamination led to the Limited (or Partial) Test Ban Treaty, signed on August 5, 1963. The treaty restricted nuclear tests from air, space, and underwater (Atomic Heritage Foundation 2016; Loeb 1991; Rubinson 2011). And while the treaty was imperfect with only three signatories at the beginning (the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Soviet Union), the ban succeeded in significantly curbing atmospheric release of radioactive isotopes.

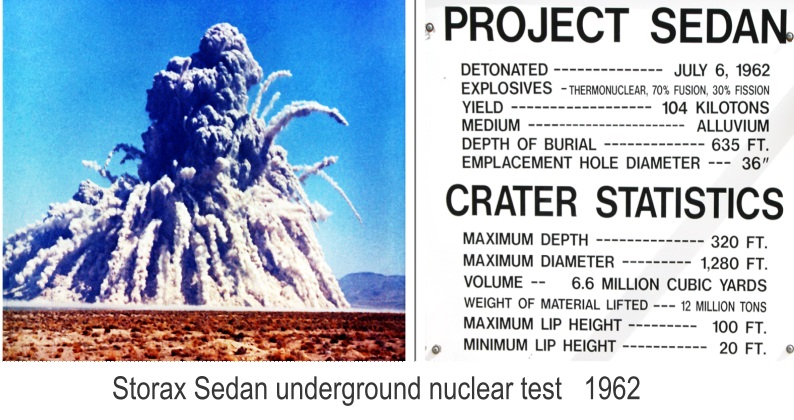

After the entry into force of the partial test ban, almost 1,500 underground nuclear tests were conducted globally. Of the 1,030 US nuclear tests, nearly 80 percent, or 815 tests (See Table 1 on original ), were conducted underground, primarily at the Nevada Test Site.[1] As for other nuclear powers, the Soviet Union conducted 496 underground tests, mostly in the Semipalatinsk region of Kazakhstan, France conducted 160 underground tests, the United Kingdom conducted 24, and China 22. These underground nuclear tests were in a variety of geologic formations (e.g., basalt, alluvium, rhyolite, sandstone, shale) to depths up to 2,400 meters.

In 1996, after some international efforts to curb nuclear testing and promote disarmament, the Comprehensive Test Ban Treaty (CTBT) was negotiated, which prohibited all nuclear explosions (General Assembly 1996). Since the negotiation of the CTBT, India and Pakistan conducted three and two underground nuclear tests, respectively, in 1998. And today, North Korea stands as the only country to have tested nuclear weapons in the 21st century.

While underground nuclear tests were chosen to limit atmospheric radioactive fallout, each test still caused dynamic and complex responses within crustal formations. Mechanical effects of underground nuclear tests span from the prompt post-detonation responses to the enduring impacts resulting in radionuclide release, dispersion, and migration through the geosphere. Every test of nuclear weapons adds to a global burden of released radioactivity (Ewing 1999)…………………………………………………………………………

………………………………………………………………….. Containment failures and nuclear accidents

Underground nuclear tests are designed to limit radioactive fallout and surface effects. However, containment methods are not foolproof, and radioisotopes, which are elements with neutrons in excess making them unstable and radioactive, can leak into the surrounding environment and atmosphere, posing potential risks to ecosystems and human health.

Instances of radiation leaks were not uncommon…………………………………..

Unintended radioactive releases from underground nuclear tests occurred through venting or seeps, where fission products and radioactive materials were uncontrollably released, driven by pressure from shockwave-induced steam or gas. In rare cases, more serious nuclear accidents occurred due to incomplete geological assessments of the surrounding medium in preparation for the test. A notable example of accidental release is the Baneberry underground nuclear test on December 18, 1970, which, according to the federal government, resulted in an “unexpected and unrecognized abnormally high water content in the medium surrounding the detonation point” ……………………………………………………………………………………………

Mechanical and radiation effects of underground nuclear tests

Three main factors affect the mechanical responses of underground nuclear tests: the yield, the device placement (i.e., depth of burial, chamber geometry, and size), and the emplacement medium (i.e., rock type, water content, mineral compositions, physical properties, and tectonic structure). These factors influence the physical response of the surrounding geological formations and the extent of ground displacement, which, in turn, determine the radiation effects by influencing the timing and fate of the radioactive gas release.

Every kiloton of explosive yield produces approximately 60 grams (3 × 1012 fission product atoms) of radionuclides (Smith 1995; Glasstone and Dolan 1977). Between 1962 and 1992, underground nuclear tests had a total explosive yield of approximately 90 megatons (Pravalie 2014), producing nearly 5.4 metric tons of radionuclides. ……………………………………………….

……………………………..The partitioning of radionuclides between the melt glass and rubble significantly impacts the subsequent transfer of radioactivity to groundwater.

…………………………Temperatures produced by large explosions can change the permeability, porosity, and water storage capacity by creating new fractures, cavities, and chimneys……………………. The explosion also affects the porosity of the surrounding rock. For example, a fully contained explosion of 12.5-kiloton yield in Degelen Mountain at the former Soviet Union’s Semipalatinsk test site resulted in up to a six-fold increase in porosity within the crush zone surrounding the cavity (Adushkin and Spivak 2015). Increased permeability and porosity of the surrounding rock can lead to more radionuclides being released, as more groundwater can pass through the geologic formation.

Hydrogeology and release of radioactivity

The main way contaminants can be moved from underground test areas to the more accessible environment is through groundwater flow. …………………………………………..

Given their long half-lives (Table 2 on original ), the ability of plutonium isotopes to migrate over time raises concerns about the long-term impacts and challenges in managing radioactive contamination.

In all these cases, colloid-facilitated transport allowed for the migration of radioactive particles through groundwater flow over an extended period—long after the nuclear tests or discharge occurred (Novikov et al. 2006). ………………………

The risks associated with the environmental contamination from underground nuclear tests have often been considered low due to the slow movement of the groundwater and the long distance that separates it from publicly accessible groundwater supplies. But these studies demonstrate that apart from prompt effect of radioactive gas releases from instantaneous changes in geologic formations, long-term effects persist due to the evolving properties of the surrounding rocks long after the tests. Long-lived radionuclides can be remarkably mobile in the geosphere. Such findings underscore the necessity for sustained long-term monitoring efforts at and around nuclear test sites to evaluate the delayed impacts of underground nuclear testing on the environment and public health.

Enduring legacy

Nearly three decades after the five nuclear-armed states under the CTBT stopped testing nuclear weapons both in the atmosphere and underground, the effects of past tests persist in various forms—including environmental contamination, radiation exposure, and socio-economic repercussions—which continue to impact populations at and near closed nuclear test sites (Blume 2022). The concerns are greater when the test sites are abandoned without adequate environmental remediation. This was the case with the Semipalatinsk test site in Kazakhstan that was left unattended after the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, before a secret multi-million effort was made by the United States, Russia, and Kazakhstan to secure the site (Hecker 2013). The abandonment resulted in heavy contamination of soil, water, and vegetation, posing significant risks to the local populations (Kassenova 2009).

In 1990, the US Congress acknowledged the health risks from nuclear testing by establishing the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act (RECA), which provides compensation to those affected by radioactive fallout from nuclear tests and uranium mining. Still, there are limitations and gaps in coverage that leave many impacted individuals, including the “downwinders” from the Trinity test site without compensation for their radiation exposure (Blume, 2023). The Act is set to expire in July 2024, potentially depriving many individuals without essential assistance. Over the past 30 years, the RECA fund paid out approximately $2.5 billion to impacted populations (Congressional Research Service 2022). For comparison, the US federal government spends $60 billion per year to maintain its nuclear forces (Congressional Budget Office 2021).

As the effects of nuclear testing still linger, today’s generations are witnessing an increasing concern at the possibility of a new arms race and potential resumption of nuclear testing (Drozdenko 2023; Diaz-Maurin 2023). The concern is heightened by activities in China and North Korea and with Russia rescinding its ratification of the CTBT. Even though the United States maintains a moratorium on non-subcritical nuclear tests, its decision not to ratify the test ban treaty shows a lack of international leadership and commitment. As global tensions and uncertainties arise, it is critical to ensure global security and minimize the risks to humans and the environment by enforcing comprehensive treaties like the CTBT. Transparency at nuclear test sites should be promoted, including those conducting very-low-yield subcritical tests, and the enduring impacts of past nuclear tests should be assessed and addressed.

Endnotes………………………………………………………………more https://thebulletin.org/premium/2024-03/environmental-impacts-of-underground-nuclear-weapons-testing/?utm_source=Newsletter&utm_medium=Email&utm_campaign=MondayNewsletter04152024&utm_content=NuclearRisk_EnvironmentalImpactsNuclearTests_03072024

No comments yet.

-

Archives

- February 2026 (127)

- January 2026 (308)

- December 2025 (358)

- November 2025 (359)

- October 2025 (376)

- September 2025 (258)

- August 2025 (319)

- July 2025 (230)

- June 2025 (348)

- May 2025 (261)

- April 2025 (305)

- March 2025 (319)

-

Categories

- 1

- 1 NUCLEAR ISSUES

- business and costs

- climate change

- culture and arts

- ENERGY

- environment

- health

- history

- indigenous issues

- Legal

- marketing of nuclear

- media

- opposition to nuclear

- PERSONAL STORIES

- politics

- politics international

- Religion and ethics

- safety

- secrets,lies and civil liberties

- spinbuster

- technology

- Uranium

- wastes

- weapons and war

- Women

- 2 WORLD

- ACTION

- AFRICA

- Atrocities

- AUSTRALIA

- Christina's notes

- Christina's themes

- culture and arts

- Events

- Fuk 2022

- Fuk 2023

- Fukushima 2017

- Fukushima 2018

- fukushima 2019

- Fukushima 2020

- Fukushima 2021

- general

- global warming

- Humour (God we need it)

- Nuclear

- RARE EARTHS

- Reference

- resources – print

- Resources -audiovicual

- Weekly Newsletter

- World

- World Nuclear

- YouTube

-

RSS

Entries RSS

Comments RSS

Leave a comment