Chess, cards and catnaps in the heart of America’s nuclear weapons complex

At Los Alamos National Laboratory, workers collect full salaries for doing nothing

Across those decades, the notion of keeping secrets from adversaries has simultaneously morphed into keeping secrets from the American public — and regulators.

| by Alicia Inez Guzmán. Searchlight New Mexico, 8 Nov 23 |

| A few days after beginning a new post at Los Alamos National Laboratory, Jason Archuleta committed a subversive act: He began to keep a journal. Writing in a tiny spiral notebook, he described how he and his fellow electricians were consigned to a dimly lit break room in the heart of the weapons complex. “Did nothing all day today over 10 hrs in here,” a July 31 entry read. “This is no good for one’s mental wellbeing or physical being.” |

“I do hope to play another good game of chess,” noted another entry, the following day.

A journeyman electrician and proud member of the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers Local 611, Archuleta had been assigned to Technical Area 55 back in July. He had resisted the assignment, knowing that it was the location of “the plant,” a sealed fortress where plutonium is hewn into pits — cores no bigger than a grapefruit that set off the cascade of reactions inside a nuclear bomb. The design harks back to the world’s first atomic weapons: “Gadget,” detonated at the Trinity Test Site in New Mexico in 1945, and “Fat Man,” dropped on Nagasaki shortly afterward.

It has been almost that long since LANL produced plutonium pits at the scale currently underway as part of the federal government’s mission to modernize its aging stockpile. The lab, now amidst tremendous growth and abuzz with activity, is pursuing that mission with single-minded intensity. Construction is visible in nearly every corner of the campus, while traffic is bumper to bumper, morning and evening, as commuters shuttle up and down a treacherous road that cuts across the vast Rio Grande Valley into the remote Pajarito Plateau on the way to the famous site of the Manhattan Project.

But from the inside, Archuleta tells a different story: that of a jobsite in which productivity has come to a standstill. With few exceptions, he says, electricians are idle. They nap, study the electrical code book, play chess, dominoes and cards. On rare occasions, they work, but as four other journeymen (who all requested anonymity for fear of retaliation) confirmed, the scenario they describe is consistent. At any given time, up to two dozen electricians are cooling their heels in at least three different break rooms. LANL officials even have an expression for it: “seat time.”

The lab recognizes that the expansion at TA-55, and especially the plant, presents challenges faced by no other industrial setting in the nation. The risk of radiation exposure is constant, security clearances are needed, one-of-a-kind parts must be ordered, and construction takes place as the plant strives to meet its quota. That can mean many workers sit for days, weeks, or even, according to several sources, months at a time.

“I haven’t seen months,” said Kelly Beierschmitt, LANL’s deputy director of operations, “It might feel like months,” he added, citing the complications that certain projects pose. “If there’s not a [radiation control technician] available, I’m not gonna tell the craft to go do the job without the support, right?”

Such revelations come as red flags to independent government watchdogs, who note that the project is already billions of dollars over budget and at least four years behind schedule. They say that a workplace filled with idle workers is not merely a sign that taxpayer money is being wasted; more troublingly, it indicates that the expansion is being poorly managed.

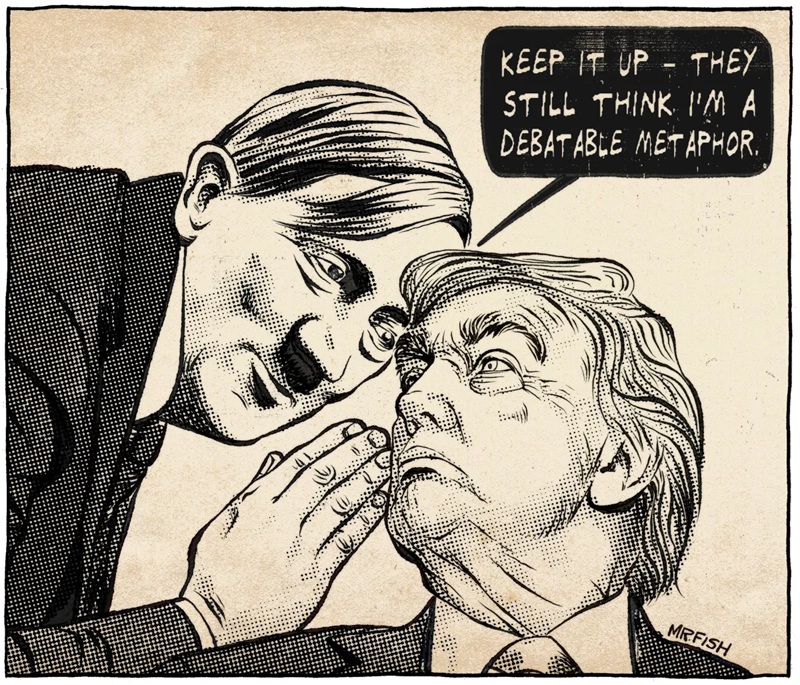

“If you have a whistleblower claiming that a dozen electricians have been sitting around playing cards for six months on a big weapons program, that would seem to me to be a ‘where there is smoke, there is fire’ moment,” said Geoff Wilson, an expert on federal defense spending at the independent watchdog Project on Government Oversight.

Given the secrecy that surrounds LANL, it is virtually impossible to quantify anything having to do with the lab. That obsession is the subject of Alex Wellerstein’s 2021 book, “Restricted Data: The History of Nuclear Secrecy in the United States.” Wellerstein, a historian of science at Stevens Institute of Technology, traces that culture of secrecy from the earliest years of the Manhattan Project into the present. Across those decades, the notion of keeping secrets from adversaries has simultaneously morphed into keeping secrets from the American public — and regulators.

“What secrecy does is it creates context for a lack of oversight,” said Wellerstein in a recent interview. “It shrinks the number of people who might even be aware of an issue and it makes it harder — even if things do come out — to audit.”

The code of secrecy at LANL is almost palpable. The lab sits astride a forbidding mesa in northern New Mexico some 7,500 feet above sea level, protected on the city’s western flank by security checkpoints. Its cardinal site, TA-55, is ringed by layers of razor wire and a squadron of armed guards, themselves bolstered by armored vehicles with mounted turrets that patrol the perimeter day and night. No one without a federal security clearance is allowed to enter or move about without an escort — even to go to the bathroom. Getting that clearance, which requires an intensive background investigation, can take up to a year.

Sources for this story, veterans and newcomers alike, said they fear losing their livelihoods if they speak publicly about anything to do with their work. Few jobs in the region, much less the state (one of the most impoverished in the nation), can compete with the salaries offered by LANL. Here, journeyman electricians can earn as much as $150,000 a year; Archuleta makes $53 per hour, almost 70 percent more than electricians working at other union sites.

Nevertheless, in late September, Archuleta lodged a complaint with the Inspector General’s office alleging time theft. He and two other workers told Searchlight New Mexico that their timesheets – typically filled out by supervisors – have shown multiple codes for jobs they didn’t recognize or perform. To his mind, the situation is “not just bordering on fraud, waste and abuse, it’s crossing the threshold.”

………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………“By all the normal measures our society uses to evaluate cost, benefit, risk, reliability, and longevity, this latest attempt has now already failed as well,” said Greg Mello of the Los Alamos Study Group (LASG), a respected nonprofit that has been monitoring LANL for 34 years. “Federal decision makers will have to ask ‘Will the LANL product still be worth the investment,’” Mello said, referring to the plant, which will have exceeded its planned lifetime of 50 years by 2028.

The cogs of this arms race have been turning for years. In May 2018, a few months after President Donald Trump tweeted that he had a much “bigger & more powerful” nuclear button than North Korea’s Kim Jong Un, the Nuclear Weapons Council certified a recommendation to produce plutonium pits at two sites.

That recommendation was enacted into law by Congress, which in 2020 called for an annual quota of plutonium pits — 30 at LANL and 50 at the Savannah River plutonium processing facility in South Carolina — by 2030. According to the LASG, the cost per pit at LANL is greater than Savannah River. The organization estimates that each one will run to approximately $100 million.

Whether such production goals are achievable is another question: Just getting those sites capable of meeting the quota will cost close to $50 billion—and take up to two decades from the project’s start. After that, another half a century may pass before the nation’s approximately 4,000 plutonium pits are all upgraded, according to the calculations of Peter Fanta, former deputy assistant secretary of defense for nuclear matters.

…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………Plutonium is one of the most volatile and enigmatic of all the elements on the periodic table. It ages on the outside like other metals, while on the inside, “it’s constantly bombarding itself through alpha radiation,” as Siegfried Hecker, a former LANL director and plutonium metallurgist put it. The damage is akin, in his words, to “rolling a bowling ball through [the plutonium’s] crystal structure.” Most of it can be healed, but about 10 percent can’t. “And that’s where the aging comes in.”

The renewed urgency dodges the most resounding “unanswered question at the heart of the U.S.’s nuclear arsenal,” Stephen Young, the Washington representative for the Global Security program at the Union of Concerned Scientists, wrote in “Scientific American.” “What is the lifetime of a pit?” And why hasn’t the NNSA — the federal agency tasked with overseeing the health of the nuclear weapons stockpile — dedicated the resources to finding out?

“It seems entirely possible that this was not an oversight on the part of NNSA but reflects that the agency does not want to know the answer,” Young went on. With novel warhead designs on the horizon, it was entirely plausible, he posited, that the NNSA wasn’t merely seeking to replace old pits but instead wanted to populate entirely new weapons — a desire driven less by science than by politics.

Booms and blind spots

This uncertainty has worked in LANL’s favor, propelling the mission forward and all but securing the lab’s transformation. As Beierschmitt, the deputy director of operations, publicly described the lab’s goals this summer: “Keep spending and hiring.”

Meanwhile, the Government Accountability Office, which investigates federal spending and provides its findings to Congress, has pointed to a gaping blind spot in the mission. A January report detailed how the NNSA lacked a comprehensive budget and master schedule for the entire U.S. nuclear weapons complex — essential for achieving the goal of producing 80 pits per year. The agency, in other words, has thus far failed to outline what it needs to do to reach its target — or what the overall cost will be, the GAO concluded.

“How much they’ve spent is pretty poorly understood because it shows up in so many different buckets across the budget,” said Allison Bawden, the GAO’s director of natural resources and environment. “We tried to identify these buckets of money ultimately tied to supporting the pit mission. But it’s never presented that way by NNSA, so it’s very difficult to look across the entire pit enterprise and say, ‘this is how much has been spent, and this is how much is needed going forward.’” The GAO includes the DOE on its biennial list of federal agencies most vulnerable to fraud, waste and abuse — and has done so since 1990. A major reason is the Möbius strip of contractors and subcontractors working on DOE-related projects at any given time.

The DOE, for instance, oversees the NNSA, which oversees Triad National Security — a company owned by Battelle Memorial Institute, the Texas A&M University and the University of California. Triad oversees its own army of subcontractors on lab-related projects, including construction, demolition and historic preservation. And many of those subcontractors outsource their work to yet other subcontractors, creating money trails so byzantine they defy tracking.

But one thing is known: Subcontractors will rake in billions of dollars. “We expect to be executing at least $5.5 billion in construction over the next five years and $2.5 billion in subcontracting labor and materials,” Beierschmitt said at a 2019 forum.

“Most people think that for something so giant and so supposedly important to the nation, there would be some kind of well-thought through plan,” said Mello of LASG. “There is no well-thought through plan. There never has been.”

Secrets on the plateau

……………………………………………….. Over time, systems at LANL and across the U.S. weapons complex have ossified into “their own little universes,” said Wellerstein, the science historian. “And when you combine that with the kind of contractor system they use for nuclear facilities, you create the circumstances where there’s very little serious oversight and ample opportunities and incentives for everybody to pat themselves on the back for a job well done…………………………………………………….. https://searchlightnm.org/chess-cards-and-catnaps-in-the-heart-of-americas-nuclear-weapons-complex/?utm_source=Searchlight+New+Mexico&utm_campaign=77629f0906-11%2F08%2F2023+-+Chess%2C+cards+and+catnaps&utm_medium=email&utm_term=0_8e05fb0467-77629f0906-395610620&mc_cid=77629f0906&mc_eid=a70296a261 #nuclear #antinuclear #nuclearfree #NoNukes #radioactive

No comments yet.

-

Archives

- January 2026 (201)

- December 2025 (358)

- November 2025 (359)

- October 2025 (377)

- September 2025 (258)

- August 2025 (319)

- July 2025 (230)

- June 2025 (348)

- May 2025 (261)

- April 2025 (305)

- March 2025 (319)

- February 2025 (234)

-

Categories

- 1

- 1 NUCLEAR ISSUES

- business and costs

- climate change

- culture and arts

- ENERGY

- environment

- health

- history

- indigenous issues

- Legal

- marketing of nuclear

- media

- opposition to nuclear

- PERSONAL STORIES

- politics

- politics international

- Religion and ethics

- safety

- secrets,lies and civil liberties

- spinbuster

- technology

- Uranium

- wastes

- weapons and war

- Women

- 2 WORLD

- ACTION

- AFRICA

- Atrocities

- AUSTRALIA

- Christina's notes

- Christina's themes

- culture and arts

- Events

- Fuk 2022

- Fuk 2023

- Fukushima 2017

- Fukushima 2018

- fukushima 2019

- Fukushima 2020

- Fukushima 2021

- general

- global warming

- Humour (God we need it)

- Nuclear

- RARE EARTHS

- Reference

- resources – print

- Resources -audiovicual

- Weekly Newsletter

- World

- World Nuclear

- YouTube

-

RSS

Entries RSS

Comments RSS

Leave a comment