America’s Nuclear Rules Still Allow Another Hiroshima

The bombs could not discriminate between combatants and the innocent. As many as one in seven of those killed in Hiroshima were not Japanese but Korean, amounting to roughly 20,000 people, many of whom were forcibly transported from their homes and interred in labor camps. The bombs killed Javanese, Dutch, British, Australian, American, and other prisoners of war. The U.S. survey estimated that over 90 percent of the 200 doctors and 1,800 nurses in Hiroshima were dead or injured, as well as half the personnel and patients at the teaching hospital at Nagasaki. One of the few numbers we know with precision is that, at minimum, the United States killed 4,412 schoolchildren in Hiroshima (a figure we know because teachers kept precise data on their students who were assigned to work crews around the city).

U.S. leaders must take responsibility for past nuclear atrocities.

Foreign Policy, JUNE 10, 2023,

On May 18, U.S. President Joe Biden traveled to Hiroshima, Japan, planning to meet with G-7 leaders—as well as survivors of the nuclear bombs—to discuss, among other things, reducing the risk of nuclear war. He followed in the footsteps of former U.S. President Barack Obama, who visited Hiroshima in his final year as president. In a short speech, Obama mourned the dead—but he did not express regret and, his advisors insisted, he did not apologize. Instead, Obama looked forward to a future that would come to see Hiroshima and Nagasaki “as the start of our own moral awakening.”

Biden and his administration have proven to be uncommonly committed to atoning for past domestic acts of violence and racism that still weaken the moral foundations of the United States. Interior Secretary Deb Haaland has announced a major investigation into ethnic cleansing in federal boarding schools for Native Americans, and the president has reaffirmed the government’s apology for its racist internment of Japanese Americans during the second world war. “That’s what great nations do,” Biden said in a speech commemorating the Tulsa Race Massacre, “come to terms with their dark sides.”

The United States has never had a similar moral awakening on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. On the 75th anniversary of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, Biden, then a candidate for president, wrote that “the scenes of death and destruction … still horrify us.” For too long, U.S. presidents have used passive language to refer to the bombings, evading responsibility for the act. White House spokesman John Kirby continued this tradition when he said that Biden would “pay his respects to the lives of the innocents who were killed in the atomic bomb that was dropped on Hiroshima.” The language helps Americans think of the bombings as something that happened to cities rather than as something their government did to people.

At Hiroshima, Biden said nothing about the bomb. He did not meet with bomb survivors as planned and did not deliver remarks when visiting the peace memorial. U.S. National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan stressed that Biden would be one of several leaders paying respects and it was not “a bilateral moment.”

After his trip, Biden—and the U.S. government—should begin to atone for the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, in word and in deed. A moral awakening on nuclear weapons requires that we confront not only the facts of the bombings that killed uncountable thousands of Japanese civilians, but also the policies and principles that still echo in U.S. nuclear weapons policy today.

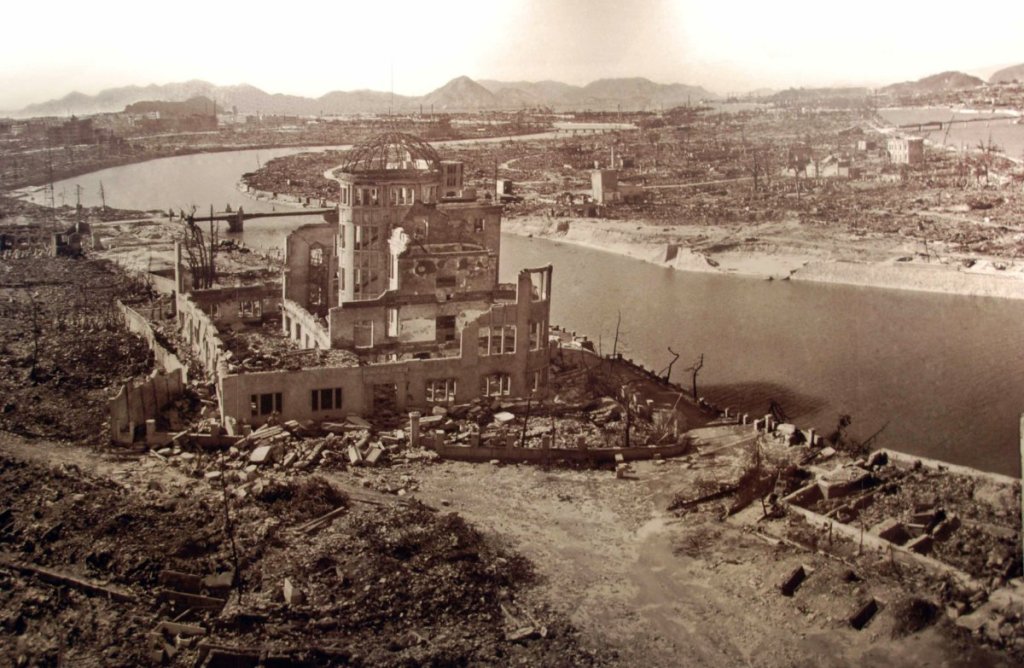

When Hiroshima was destroyed on Aug. 6, 1945, the city contained more than eight civilians for each soldier. Though a group of senior advisors had recommended that the bomb be aimed at “a military target surrounded by workers’ houses,” they did not issue orders to strike a specific target. The crew of the Enola Gay aimed the atomic bomb at Aioi Bridge, a visible landmark at the center of Hiroshima. The bomb detonated directly over nearby Shima Hospital. By November, the bomb had killed 90 percent of people who had been within one kilometer of its detonation. By the next year, more than one-third of the civilians who had been in the city during the bombing were dead. Nearly as many had been injured and would have to wait hours or days for care. More than 90 percent of the city’s doctors and nurses were killed and only three of 45 civilian hospitals were usable.

Survivors describe burned figures stumbling away from the city center, their skin hanging from their bodies, begging for water, some carrying blackened infants or their own body parts. Hospitals, churches, schools, firehouses, and public utilities all collapsed or succumbed to the flames. While two military headquarters near the center of the city were destroyed, the airfield, ordinance depots, heavy industry, and navy units clustered around the port received less damage. The fire did not reach them. If the bomb were to have been aimed at the city’s military targets, it would have been dropped two miles to the south.

The intended target of the second atomic bomb was Kokura, a city to the north that contained a military arsena………………

The bomb missed its intended target by three-quarters of a mile and detonated over the Urakami Valley, a residential area that included schools, a prison, a prisoner-of-war camp, a medical college, and a cathedral that served a large population of Catholics in the neighborhood. A half mile to the north and south, at the edges of the damage, there were two arms factories. Some of Nagasaki’s pregnant women and elderly residents had been moved to the valley precisely because it did not contain military factories.

……………. when the first plutonium bomb was ready in only three days, military personnel managing the operation on Tinian Island followed their orders to drop the bomb as soon as it was available. When he learned of Nagasaki, Truman ordered a halt to further use of nuclear weapons, saying, according to accounts of a cabinet meeting, he didn’t like the idea of killing “all those kids.”

………………………. We will never know precisely how many died in the two cities. In 1951, U.S. survey teams estimated that at least 104,000 died; in 1981, a detailed study led by Japanese researchers estimated that 210,000 civilians had died. Most other estimates fall between these figures. In most estimates, the wounded meet or exceed the dead. More than 90% of those seriously injured by the bomb had died by mid-September—but for all of those who survived, the effects of the bomb would continue. Thousands have suffered from injury, trauma, social stigma, and increased rates of miscarriage, birth defects, leukemia, and solid cancers for decades.

The bombs could not discriminate between combatants and the innocent. As many as one in seven of those killed in Hiroshima were not Japanese but Korean, amounting to roughly 20,000 people, many of whom were forcibly transported from their homes and interred in labor camps. The bombs killed Javanese, Dutch, British, Australian, American, and other prisoners of war. The U.S. survey estimated that over 90 percent of the 200 doctors and 1,800 nurses in Hiroshima were dead or injured, as well as half the personnel and patients at the teaching hospital at Nagasaki. One of the few numbers we know with precision is that, at minimum, the United States killed 4,412 schoolchildren in Hiroshima (a figure we know because teachers kept precise data on their students who were assigned to work crews around the city).

The United States’ bombs also killed American citizens in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. It is not known how many Americans died in the two cities, but before the war more U.S. immigrants had arrived from Hiroshima than any other Japanese prefecture and so were linked to the city by familial ties. After the war, as many as 3,000 Japanese-Americans returned home to the United States as victims of the atomic bombs. Furthermore, around 1,000 Japanese bomb victims would later move to the United States and become U.S. citizens. Many never identified themselves—but others organized to demand recognition and compensation from the U.S. government for medical expenses.

…………….Americans who were injured in Japan when their government dropped a nuclear bomb on them received neither recognition nor compensation.

The United States also did not provide medical care to Japanese atomic bomb victims. The Atomic Bomb Casualty Commission, established to research the effects of radiation on the human body to inform Cold War U.S. civil defense procedures, maintained a policy of not providing medical treatment to the victims. M. Susan Lindee writes, “The United States would not apologize atone for the use of atomic weapons in Japan, and it would therefore not provide medical treatment to the survivors of the bombings who were the subjects of American biomedical research.” Initially, the commission refused to share its data with Japanese physicians treating patients……..

https://foreignpolicy.com/2023/06/10/united-states-japan-hiroshima-nuclear-atomic-bomb/

No comments yet.

-

Archives

- February 2026 (256)

- January 2026 (308)

- December 2025 (358)

- November 2025 (359)

- October 2025 (376)

- September 2025 (258)

- August 2025 (319)

- July 2025 (230)

- June 2025 (348)

- May 2025 (261)

- April 2025 (305)

- March 2025 (319)

-

Categories

- 1

- 1 NUCLEAR ISSUES

- business and costs

- climate change

- culture and arts

- ENERGY

- environment

- health

- history

- indigenous issues

- Legal

- marketing of nuclear

- media

- opposition to nuclear

- PERSONAL STORIES

- politics

- politics international

- Religion and ethics

- safety

- secrets,lies and civil liberties

- spinbuster

- technology

- Uranium

- wastes

- weapons and war

- Women

- 2 WORLD

- ACTION

- AFRICA

- Atrocities

- AUSTRALIA

- Christina's notes

- Christina's themes

- culture and arts

- Events

- Fuk 2022

- Fuk 2023

- Fukushima 2017

- Fukushima 2018

- fukushima 2019

- Fukushima 2020

- Fukushima 2021

- general

- global warming

- Humour (God we need it)

- Nuclear

- RARE EARTHS

- Reference

- resources – print

- Resources -audiovicual

- Weekly Newsletter

- World

- World Nuclear

- YouTube

-

RSS

Entries RSS

Comments RSS

Leave a comment