The ABCs of a nuclear education

Then she remembered the words of her grandmother, a field nurse from Ohkay Owingeh Pueblo, who once tended to Navajo Nation tribal members affected by uranium mining and saw the health impacts of radiation exposure firsthand.

“She used to tell me, ‘Don’t ever, ever work at Los Alamos National Labs.’”

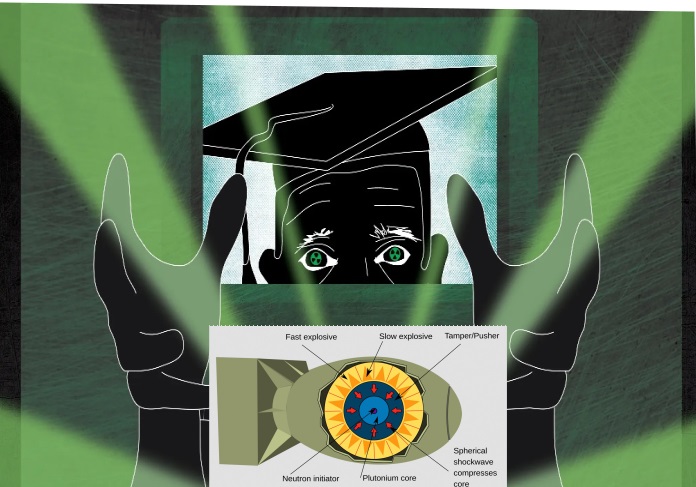

New Mexico’s local colleges are training students to work in a plutonium pit factory. What does this mean for their future — and the world’s?

Searchlight NewMexico, by Alicia Inez Guzmán, June 7, 2023

Every day, thousands of people from all parts of El Norte make the vertiginous drive up to Los Alamos National Laboratory. It’s a trek that generations of New Mexicans have been making, like worker ants to the queen, from the eastern edge of the great Tewa Basin to the craggy Pajarito Plateau.

All in the pursuit of “good jobs.”

Some, inevitably, are bound for that most secretive and fortified place, Technical Area 55, the very heart of the weapons complex — home to PF-4, the lab’s plutonium handling facility, with its armed guards, concrete walls, steel doors and sporadic sirens. To enter “the plant,” as it’s known, is to get as close as possible to the existential nature of the nuclear age.

For 40 years, some 250 workers were tasked, mostly, with research and design. But a multibillion-dollar mission to modernize the nation’s nuclear arsenal has brought about “a paradigm shift,” in the words of the Defense Nuclear Facilities Safety Board, a federal watchdog. Today, the plant is in the middle of a colossal expansion — growing from a single, aged building to what the safety board calls “a large-scale production facility for weapon components with the largest number of workers in its history.”

In short, the plant is slated to become a factory for making plutonium pits, the essential core of every nuclear warhead.

Four years ago, LANL began laying the groundwork for this expansion by searching out and shaping a highly trained labor pool of technicians to handle fissile materials, machine the parts for weapons, monitor radiation and remediate nuclear waste. The lab turned to the surrounding community, as it often had, tapping New Mexico’s small regional institutions — colleges that mostly serve minority and low-income students. The plan, as laid out in a senate subcommittee meeting, set forth a college-to-lab pipeline — a “workforce of the future.”

Taken altogether, Santa Fe Community College, Northern New Mexico College and the University of New Mexico’s Los Alamos campus are set to receive millions of federal dollars for their role in preparing and equipping that workforce. They’ve graduated 74 people to date, many of whom will end up at TA-55……………………………………

For many local families, the lab has been a gateway to the American dream. Its high wages have afforded generations of Norteños a chance at the good life — new houses, new cars, land ownership, higher education for their kids. Indeed, to work there is to become part of the region’s upper crust.

It carries a legacy of illness, death and environmental racism for countless others. History tells of a long practice of hiring local Hispano and Pueblo communities to staff some of the most dangerous positions, a practice that has its origins in the early years of the lab, as Myrriah Gómez described in her 2022 book “Nuclear Nuevo México.”

New Mexico’s academic institutions have for decades served as LANL’s willing partner, feeding students into the weapons complex with high school internships, undergraduate student programs; graduate and postdoc programs; and apprenticeships for craft trades and technicians. The lab heavily recruits at most local colleges with the assurance of opportunities not easily found in New Mexico.

Talavai Denipah-Cook can still remember LANL representatives plying her with promises of a high-paying job and good benefits at an American Indian Sciences and Engineering Society conference years ago. At the time, she was a student at a local high school, and the future that they painted looked bright.

“I was like, ‘Wow, that sounds really intriguing.’ We don’t get that around here, especially as people of color,” said Denipah-Cook, now a program manager in the Environmental Health and Justice Program at Tewa Women United, an Indigenous nonprofit based in Española.

Then she remembered the words of her grandmother, a field nurse from Ohkay Owingeh Pueblo, who once tended to Navajo Nation tribal members affected by uranium mining and saw the health impacts of radiation exposure firsthand.

“She used to tell me, ‘Don’t ever, ever work at Los Alamos National Labs.’” ……………………………………………………………………………………………………….

“The lab has never had to be accountable for their promises,” said Greg Mello, of the Los Alamos Study Group, an influential anti-nuclear nonprofit based in Albuquerque. “Could they be a factory? Could they produce pits reliably? No. Not at all.”

LANL, regardless, was tapped as one of two sites — the other being the Savannah River plutonium processing facility in South Carolina — to produce an annual quota of “no fewer than 80 such pits by 2030,” according to the Fiscal 2020 National Defense Authorization Act. With this, LANL has been authorized to produce 30 pits per year by 2026.

What’s being proposed is so huge it has no precedent, said Jay Coghlan, executive director of Nuclear Watch New Mexico, an anti-nuclear advocacy organization in Santa Fe.

“Here we have this arrogant agency that thinks it can just impose expanded bomb production on New Mexico,” said Coghlan, referring to the National Nuclear Security Administration, the lead agency for pit production. “They do not have credible cost estimates and they do not have a credible plan for production. But yet they expect New Mexicans to bear the consequences.”

The costs, according to the Los Alamos Study Group, will come to some $46 billion by 2036 — the earliest the NNSA says it can hit 80 pits per year at the two sites. It’s roughly the same amount of money it would take to rebuild every single failing bridge in America.

To support the pit mission at LANL, the NNSA estimates the lab will need 4,100 full-time employees, including scientists and engineers, security guards, maintenance and craft workers, and “hard-to-fill positions,” as LANL has dubbed the pipeline jobs.

More costly than the Manhattan Project in its day, the NNSA program is the most expensive in the agency’s history. It is also destined, Coghlan and others say, to collapse under its own weight. Both Los Alamos and Savannah River are, according to federal documents, billions of dollars over budget and years behind schedule.

Money, waste and risk

In the meantime, LANL’s budget has increased by 130 percent over the past five years, according to a June 2022 report by the Government Accountability Office. There’s no real way to determine how much money LANL will need to reach its quota.

…………………………………………………………. Radiation 101: Students get prepped for pit work

Last spring, assistant professor Scott Braley taught two back-to-back introductory courses to 13 future radiation control technicians at NNMC. His lectures covered a host of topics: the history of “industrial-scale” radiation accidents worldwide, algebraic formulas to determine the correlation between individual cancer and workplace exposure, and maximum permissible doses for future workers like themselves. The rates are higher than for the general public, Braley explained, because, for one, radiation workers “have accepted a higher risk.”

……………………………. Much of the college programs and their curricula center around minimizing risk. But because the possibility of serious harm at LANL is much higher than in most jobs, the programs present an ethical dilemma: Who are the people bearing the risk?

“What does it mean to assume that exposure is acceptable at all?” asked Eileen O’Shaughnessy, cofounder of Demand Nuclear Abolition. “Because the thing about radiation is it’s cumulative and any amount is unsafe.”

………………….. “You realize, yes, they are paying you well, but you’re being put in situations that you have no idea about,” said the retired machinist, a man with over two decades of experience working at the lab, much of it at the plant. He asked to remain anonymous for fear of retaliation. “It’s the mentality at the lab,” he said. “They don’t really think that people that are techs are even really worth much.”

A powerful neighbor

Dueling perspectives in El Norte reveal the chasms around the lab and, in particular, what some consider the Manhattan Project’s original sin: Its use of eminent domain to force Indigenous and Hispano people off their farms and sacred lands on the Pajarito Plateau. Its arrival, oral histories hold, spelled the end of land-based living.

……………………. As the single largest employer in northern New Mexico, LANL’s horizon of influence is vast. And with billions more dollars flooding in, its sway in almost every sphere — economics, politics, education — seems only to grow.

“It is hard for us at the Los Alamos Study Group to see how New Mexico can ever develop if LANL becomes a reliable, enduring pit factory,” said Greg Mello, the executive director. “We see it as a death sentence for economic and social development in Northern New Mexico.”

Despite the lab’s omnipresence, economic gains have been relatively limited. While Los Alamos County has one of the highest median household incomes in the nation, the surrounding communities — including Española — are among the poorest in the state.

The most damning indication of that disparity came in a draft report from the University of New Mexico’s Bureau of Business and Economic Research, which showed that the lab actually cost Rio Arriba County $2.6 million and Santa Fe County $2.2 million in fiscal year 2017.

According to the Rio Grande Sun, LANL suppressed that information in the report’s final version. And though LANL jobs are by far the most competitive in the region, the trickle-down hasn’t amounted to collective uplift.

“LANL has been a bad neighbor,” charged Warren. “If the economic benefits are so good for them to continue their work and expand, you would think the communities around here would be doing better. But we’re not.” https://searchlightnm.org/the-abcs-of-a-nuclear-education/

1 Comment »

Leave a comment

-

Archives

- February 2026 (228)

- January 2026 (308)

- December 2025 (358)

- November 2025 (359)

- October 2025 (376)

- September 2025 (258)

- August 2025 (319)

- July 2025 (230)

- June 2025 (348)

- May 2025 (261)

- April 2025 (305)

- March 2025 (319)

-

Categories

- 1

- 1 NUCLEAR ISSUES

- business and costs

- climate change

- culture and arts

- ENERGY

- environment

- health

- history

- indigenous issues

- Legal

- marketing of nuclear

- media

- opposition to nuclear

- PERSONAL STORIES

- politics

- politics international

- Religion and ethics

- safety

- secrets,lies and civil liberties

- spinbuster

- technology

- Uranium

- wastes

- weapons and war

- Women

- 2 WORLD

- ACTION

- AFRICA

- Atrocities

- AUSTRALIA

- Christina's notes

- Christina's themes

- culture and arts

- Events

- Fuk 2022

- Fuk 2023

- Fukushima 2017

- Fukushima 2018

- fukushima 2019

- Fukushima 2020

- Fukushima 2021

- general

- global warming

- Humour (God we need it)

- Nuclear

- RARE EARTHS

- Reference

- resources – print

- Resources -audiovicual

- Weekly Newsletter

- World

- World Nuclear

- YouTube

-

RSS

Entries RSS

Comments RSS

So ugly, the bomb and plutonium are. What a terrible job,.working around megadeath, every day. Insane greed. Insane self destruction